Figures & data

Table 1 Summary of some of the physical and personal factors that can affect an individual’s experience of life with physical impairment or disability.

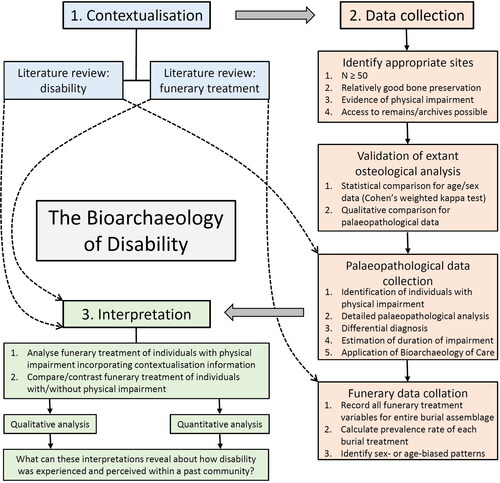

fig 1 Flowchart outlining the three phases of the bioarchaeological approach used in this research. Image by S Bohling.

fig 2 Map identifying the locations of the nine early medieval cemeteries included in this research. Source: Google My Maps [online] Base map: Light Landmass; Map data © 2022 GeoBasis-DE/BKG (© 2009), Google.

![fig 2 Map identifying the locations of the nine early medieval cemeteries included in this research. Source: Google My Maps [online] Base map: Light Landmass; Map data © 2022 GeoBasis-DE/BKG (© 2009), Google.](/cms/asset/5ea6c2c9-0018-42f5-94f7-8ff58d1dd9ff/ymed_a_2204666_f0002_c.jpg)

Table 2 Demographic summary of the nine early medieval cemeteries included in this research.

Table 3 Cohen’s weighted κ values for sex and age comparison for each site.

Table 4 Brief palaeopathological summaries and descriptions of funerary treatment for the individuals with physical impairment.

fig 3 Butler’s Field 6. Pseudarthroses on the posterior surfaces of the right and left scapulae of BF-6 as a result of bilateral posterior dislocation of both shoulders. Photograph by S Bohling with permission of the Corinium Museum.

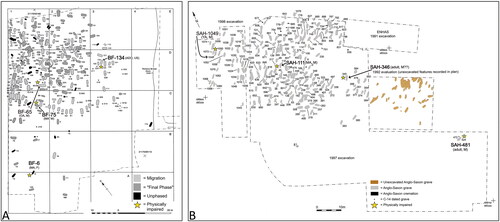

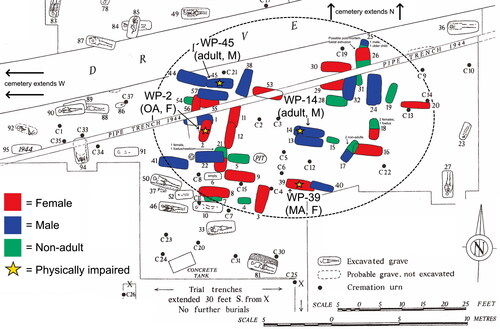

fig 4 Maps to illustrate the burial locations of individuals with physical impairment. (A) Butler’s Field cemetery. Note that BF-6 is at a considerable distance from the main burial concentration. (B) St Anne’s Hill cemetery. Note that SAH-481 is away from the main burial concentration. Image A reproduced from Boyle et al Citation2011, fig 6.4, and modified by lead author, © Oxford Archaeology. Image B reproduced from Doherty and Greatorex Citation2016, fig 3.1, and modified by lead author, included with permission of Archaeology South-East, © 2016 UCL Archaeology South-East.

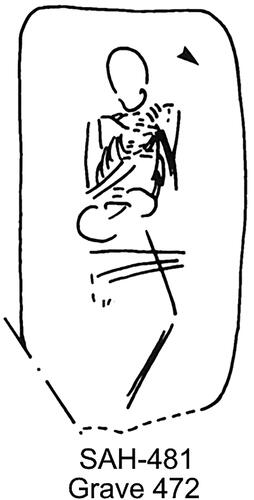

fig 5 St Anne’s Hill 481. Grave drawing of SAH-481 demonstrating nonnormative leg positioning. Not drawn to scale. Image reproduced from Doherty and Greatorex Citation2016, fig 4.20, and modified by lead author, included with permission of UCL Archaeology South-East, © UCL Archaeology South-East.

fig 6 Worthy Park cemetery. Detail of the cluster of individuals with physical impairment, also demonstrating the location of males, females, non-adults, and double burials containing females and non-adults. Image reproduced from Hawkes and Grainger, Citation2003, fig 1.5, and modified by lead author, © Oxford University School of Archaeology.

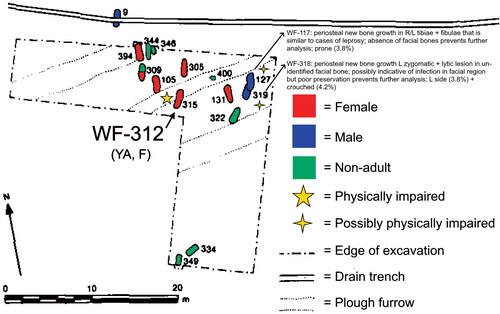

fig 7 Detail of the south-western corner of the Watchfield cemetery. Identifying the location of females, non-adults, and the individual with physical impairment. Note that the only two males in this area are considered possibly physically impaired (WF-117 in Grave 127; WF-318 in Grave 319), but fragmentation and poor preservation prevented further analysis (see Bohling Citation2020, section 7.8 for further details). NB: small, black numbers represent grave context numbers. Image reproduced from Scull et al Citation1992, fig 25, drawn by C Scull and modified by lead author, © Royal Archaeological Institute.

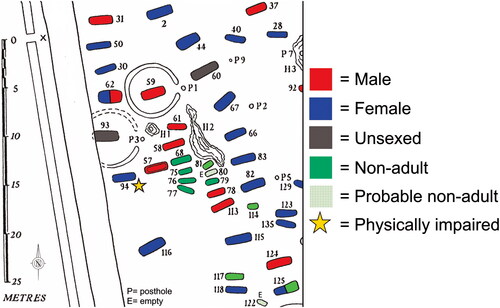

fig 8 Detail of area surrounding FS-94 in the Finglesham cemetery. Image reproduced from Hawkes and Grainger Citation2006, fig 1.3, and modified by lead author, © Oxford University School of Archaeology.

fig 9 Norton East Mill 91. Fracture and consequent shortening of the right femur of NEM-91 (in comparison to left) which probably resulted in an abnormal gait. Photograph by S Bohling with permission of Tees Archaeology.

Table 5 Comparisons between the frequencies of prone, flexed, and crouched burials at the nine cemeteries analysed.

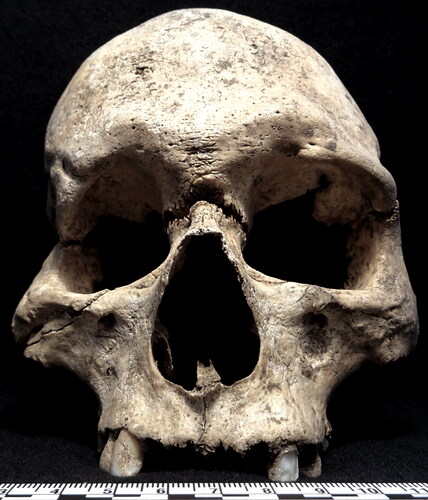

fig 10 Butler’s Field 65. Well-healed trauma to the right side of the viscerocranium of BF-65 resulting in asymmetrical eye orbits and possible soft tissue abnormalities that would have been noticeable in many social interactions. Scale in centimetres. Photograph by S Bohling with permission of the Corinium Museum.

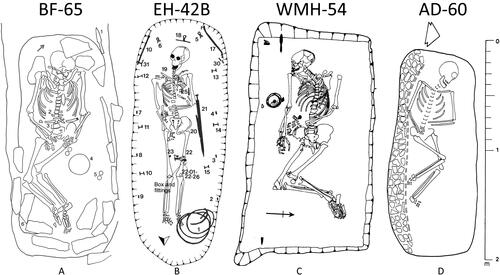

fig 11 In situ grave drawings for individuals with physical impairment with evidence of increased burial effort. (A) BF-65, shown at 1:20 scale; (B) EH-42B, shown at 1:20 scale; (C) WMH-54, shown at 1:20 scale; (D) AD-60. Images reproduced from: (A) Boyle et al Citation1998, fig 5.12, © Oxford Archaeology; (B) Malim and Hines Citation1998, fig 3.71, reprinted with permission of the authors, © Council for British Archaeology; (C) Drawing by Mark Bennet in Bishop and Mordan Citationn.d., fig 14, © Nottinghamshire County Council; (D) Down and Welch Citation1990, fig 2.54, © Chichester District Council. All rights reserved.

fig 12 Edix Hill 42B. Bilateral rounding of the nasal aperture margins and resorption of the nasal spine of EH-42B indicative of rhinomaxillary syndrome which would have caused soft tissue abnormalities. Scale in centimetres. Photograph by S Bohling with permission of Cambridgeshire County Council.

Table 6 Comparison of grave good presence between the individuals with and without physical impairment in the nine cemeteries analysed.

Table 7 Comparison of weapon inclusion between the adult male individuals with and without physical impairment in the nine cemeteries analysed.

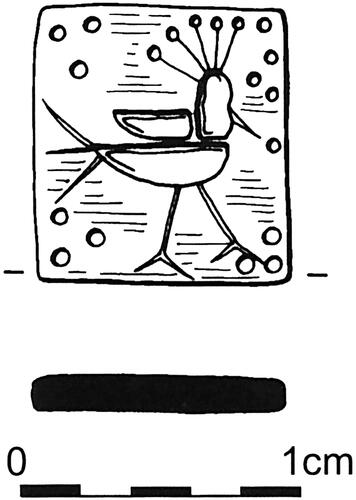

fig 13 Late-Roman copper intaglio for a bezel ring buried with St Anne’s Hill 481. Image reproduced from Doherty and Greatorex Citation2016, fig 4.20, included with permission of UCL Archaeology South-East, © UCL Archaeology South-East.