Figures & data

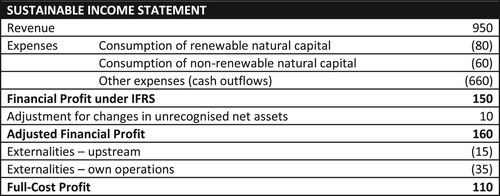

Figure 2. Income statement – from financial profit to full-cost profit. Note: (1) For simplicity of presentation, the line items from revenue to financial profit are intended as a shorthand representation of a conventional income statement, with expenses categorised according to relationship with natural capital. All other line items are concerned with adjustments that reconcile financial profit with sustainable profit. (2) Financial profit is maintained, given its central role in capital markets, but the approach also yields “full-cost profit” as a second bottom line, which serves a different, complementary informational purpose. (3) The adjustment for changes in unrecognised net assets concerns gains or losses on assets that are owned by the company but that are not fully captured on the balance sheet (for example, land carried at historical cost). Accordingly, the subtotal “adjusted financial profit” can be considered to be a “comprehensive” measure of financial profit. (4) Financial profit for the shareholder is adjusted for externalities, and thereby reconciled with full-cost profit. These are “expenses’ not actually incurred by the corporation but that would be required to be incurred in order to restore depleted natural capital. (5) Externalities might arise upstream, outside the boundary of the financial reporting entity, or else they might be consequences of activities undertaken by the reporting entity itself. These two categories are presented separately, in order that the source of the externality can be understood. Again, the presentation here is kept simple. In practice, of course, there would be numerous sources of externality, each measured with different levels of complexity. (6) As we define full-cost profit as the (hypothetical) financial profit that the company would make if it internalised its externalities, including those in its supply chain, the possibility remains that natural resources remain depleted. An accounting choice therefore arises over whether to measure replacement cost historically or currently, where the latter would require re-estimation in each subsequent accounting period (similar to that in IAS 37) for the current cost of making good prior damage. This would in turn require some form of (off balance sheet) “liability” accounting, from whichever year is deemed to be the base. There is a simple trade-off here between the costs of maintaining such a system and the increased economic relevance of the data provided .