Figures & data

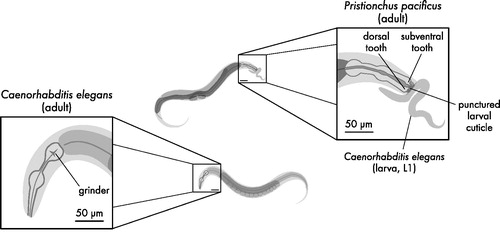

Figure 1. Pristionchus pacificus and Caenorhabditis elegans are similar in size and body form at the young adult stage. Caenorhabditis elegans possesses a grinder that it uses to lyse bacteria for consumption. Instead of a grinder, P. pacificus instead has one or two teeth that it uses to puncture the cuticle of larval C. elegans prey. The non-predatory stenostomatous dimorph of P. pacificus has only dorsal tooth, while the predation-enabled eurystomatous dimorph possesses a larger claw-like dorsal tooth and an additional subventral tooth.

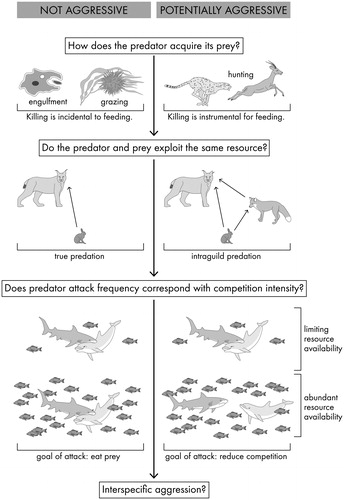

Figure 2. Three key questions are critical for determining whether a particular predatory behaviour has the potential to be aggressive. The first question establishes whether harm in predation is intentionally inflicted. The second question identifies whether the prey can be a potential competitor. Finally, the third question explores whether the predator intentionally harms the prey for interference competition.

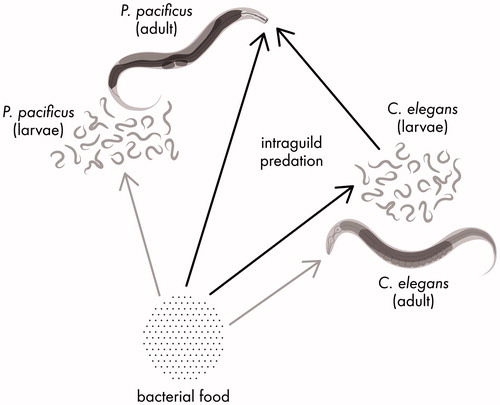

Figure 3. This food web diagram shows the directions in which different types of food travel between P. pacificus, C. elegans, and a bacterial food that both species exploit. Arrows originate from a food source and point to the organism that eats that food. Black arrows lead between direct participants in intraguild predation, while grey arrows indicate feeding interactions that are indirectly involved. The intraguild predator is adult P. pacificus, which predates on larval C. elegans as its intraguild prey. Adult and larval stages of P. pacificus and C. elegans consume bacteria.