Figures & data

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population.

Table 2. Description of male adolescent GP visitors’ and non-visitors’ behaviours, experiences and symptoms that compose four latent variables and four manifest variables.

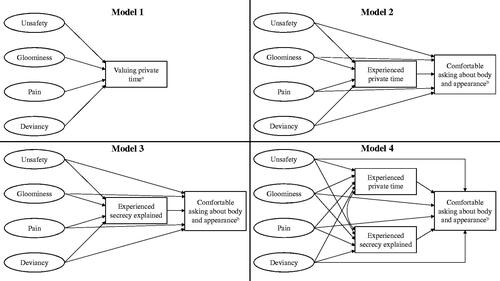

Figure 1. Structural models to study confidentiality and being comfortable asking sensitive questions in relation to mental health (unsafety, gloominess, and pain) and health-compromising behaviours (deviancy). Note that the cross-sectional design limits conclusive evidence regarding the causality in the relationships. Adjustment variables and allowed covariances are shown in Appendix A, .

aModel 1 was used for seven outcomes: valuing private time, valuing secrecy explained, experienced private time, experienced secrecy explained, being comfortable asking about body and appearance, love and relationships, and sex.

bModel 2, 3 and 4 were used for three outcomes: being comfortable asking about body and appearance, love and relationships, and sex.

Table 3. Experienced confidentiality (no, yes) and being comfortable asking sensitive questions (no, partly, yes) in relation to poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours among adolescent males, shown as approximative odds ratios.

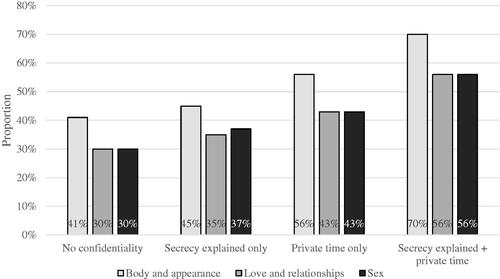

Figure 2. Proportions of adolescent males being comfortable asking about their body and appearance, love and relationships, or sex when visiting a general practitioner in relation to experienced confidentiality: if neither private time, nor secrecy explained were experienced; if secrecy explained was experienced; if private time was experienced; or both. Reports from 1200 Swedish adolescent males (Life and Health in Youth 2014).

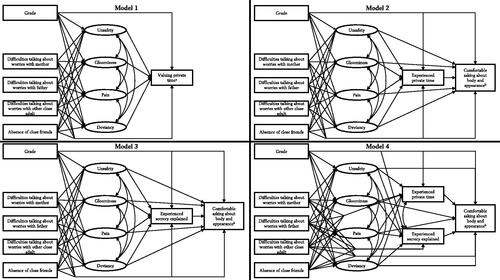

Figure A1. The structural models to study confidentiality and being comfortable asking sensitive questions in relation to poor mental health and health-compromising behaviours, here shown with all included adjustment variables and covariances. Each outcome was tested in relation to poor mental health (unsafety, gloominess, and pain) and health-compromising behaviours (deviancy), adjusted for grade (as a proxy for age) and impaired connectedness (difficulties talking about worries with mother, father, or other close adult, and absence of close friends). Covariances were allowed between the four latent variables (unsafety, gloominess, pain, and deviancy) in all models and between experienced private time and experienced secrecy explained in Model 4.

aModel 1 was used for seven outcomes: valuing private time, valuing secrecy explained, experienced private time, experienced secrecy explained, being comfortable asking about body and appearance, being comfortable asking about love and relationships, and being comfortable asking about sex.

bModel 2, 3 and 4 were used for three outcomes: being comfortable asking about body and appearance, being comfortable asking about love and relationships, and being comfortable asking about sex.