Figures & data

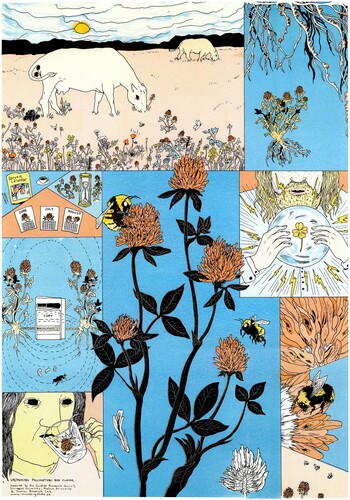

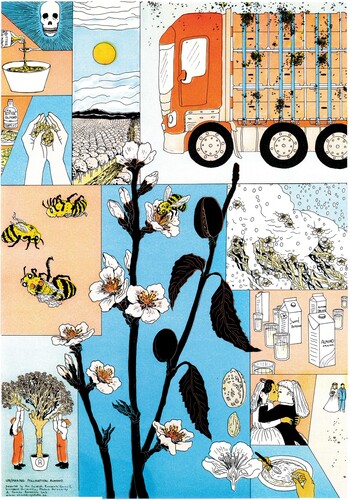

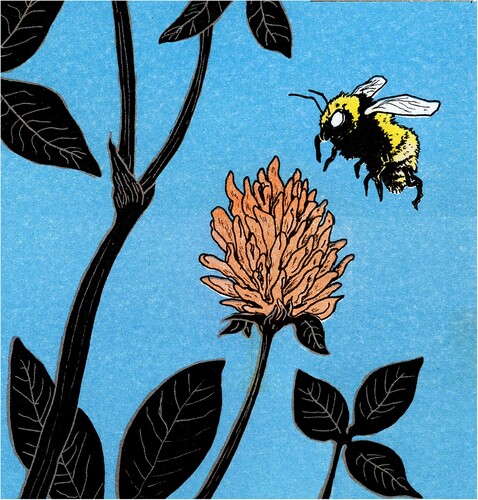

Figure 1. Plant–pollinator relationships at stake, or in some way out of sync, in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. A2 size riso printed posters, drawn with thin, clear ink lines and coloured in bright shades of orange, yellow, aqua and camel brown. Large portraits of the plants in bloom with visiting insect pollinators take a central place in the image, surrounded by a frame of smaller thickener panels – images that expand the story – different facets of a prism presenting these relationships. Red Clover is more or less dependent on one particular pollinator – the great yellow bumblebee (klöverhumla). This is because the great yellow bumblebee has a tongue that is long enough to reach all the way down into the floral barrel of the clover. The great yellow bumblebee is, however, listed as a threatened species in Sweden, partly due to the ways that landscapes are farmed. Copyright Saskia Gullstrand.

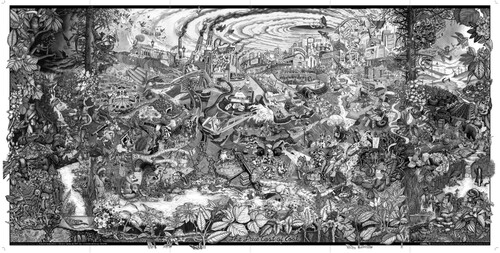

Figure 2. Plant–pollinator relationships at stake, or in some way out of sync, in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. A2 size riso printed posters, drawn with thin, clear ink lines and coloured in bright shades of orange, yellow, aqua and camel brown. Large portraits of the plants in bloom with visiting insect pollinators take a central place in the image, surrounded by a frame of smaller thickener panels – images that expand the story – different facets of a prism presenting these relationships. Almond trees, on the other hand, are less common in Sweden. Most of the almonds and the almond milk that you can buy in Sweden come from large plantations in California, where the almond trees are pollinated by bees being transported on trucks. Partly due to climate change and bioengineered varieties, there are, however, also ongoing attempts to grow and farm almonds in Southern Sweden. Copyright Saskia Gullstrand.

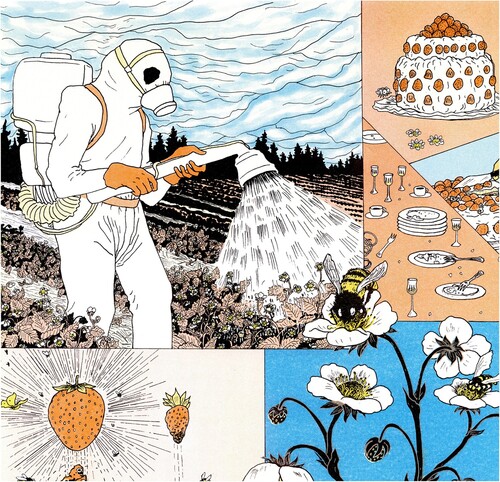

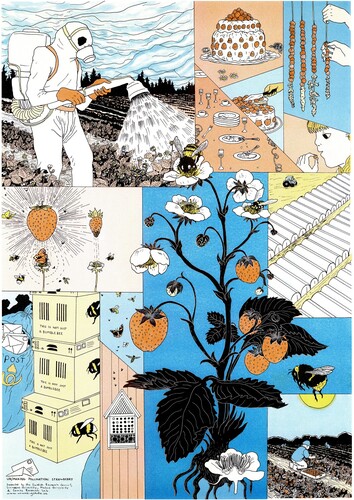

Figure 3. Plant–pollinator relationships at stake, or in some way out of sync, in Southern Sweden, Northern Europe. A2 size riso printed posters, drawn with thin, clear ink lines and coloured in bright shades of orange, yellow, aqua and camel brown. Large portraits of the plants in bloom with visiting insect pollinators take a central place in the image, surrounded by a frame of smaller thickener panels – images that expand the story – different facets of a prism presenting these relationships. Strawberries used to be accessible in Sweden only during the summer. They are a central dish at midsummer celebrations. Nowadays, you can buy strawberries all year. They are often farmed in large greenhouses. To secure a full harvest, these plants are often pollinated by bumblebees that are ordered and delivered by mail. Copyright Saskia Gullstrand.

Figure 4. The poster with red clover and the making of hand pollination tools on the dock. Photo by Li Jönsson.

Figure 5. The poster with red clover and the making of hand pollination tools on the dock. Photo by Åsa Ståhl.

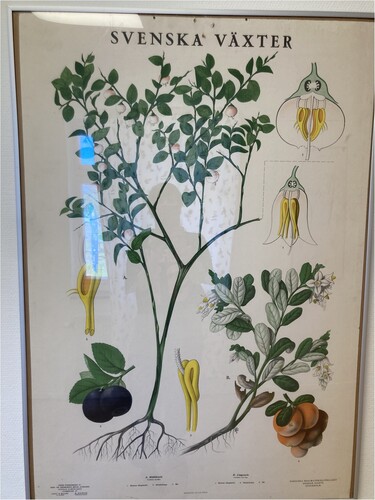

Figure 7. Example of a school poster photographed in a contemporary Swedish school, showing blueberries and lingonberries. (Photo credit: Åsa Ståhl).

Figure 8. Work material in the studio including image references such as those of Cristina Daura and Fien Jorissen. (Photo credit: Åsa Ståhl).

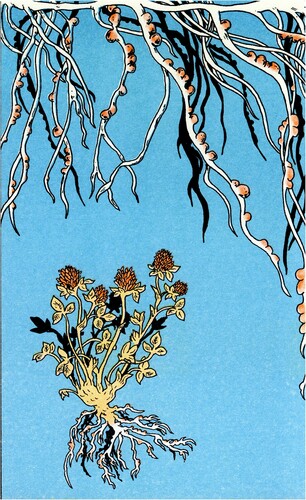

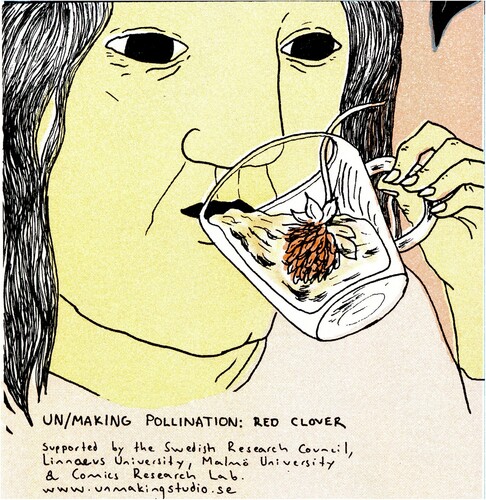

Figure 9. Some of the thickening panels. Red clover to be drunk for cooling down. Copyright: Saskia Gullstrand.

Figure 10. Some of the thickening panels. Great yellow bumblebee that is an expert pollinator for red clover. Copyright: Saskia Gullstrand.

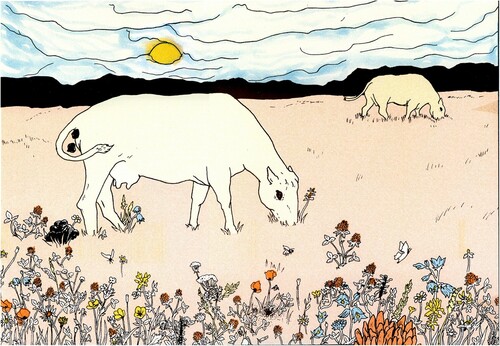

Figure 13. Two cows are grazing in a large meadow, one of them releasing a dump of thick, wet cow droppings in the grass. In the foreground, you see an abundance of wildflowers and several insects flying around. If you look closely, you’ll see a hole in the ground by the red poppies in the middle of the image – this is the entrance to a great yellow bumblebee nest. There are black silhouettes of mountains and a large yellow sun peeking out through thick clouds in the background. There are no humans in the picture, making it at first glance possible to read as an idyllic depiction of a relationship between animals and plants uncompromised by humans – an ideal state of things, where the great yellow bumblebee can thrive and continue to be involved in sexually reproducing with the red clover flowers, and destructive humans are removed. However, despite the absence of humans in this depiction of the grazing cows and the meadow that they sustain, there are humans involved. This panel shows a type of landscape that has been formed together with human agricultural practices, with small cow farms, which created adequate living conditions for the great yellow bumblebee. The image stretches through time. Are we looking at a scene from the seventeenth century or a more contemporary one? Is it a speculation on liveable futures? For whom? This type of human–pollinator–plant relationship does (still) exist in some places of Sweden (e.g. nature reserves where cows graze to keep meadows open), and it was until not very long ago a common sight. The image is thick because it holds several temporalities. It echoes of loss but also hope for the future through the suggestion that humans have managed in the past to have liveable and supportive relationships with these insect pollinators and plants.

Figure 14. An example of how the different panels thicken each other through iconic solidarity can be found in the strawberry poster. In the top left corner, workers in full protective hazmat gear are spraying the monoculture field with pesticides. A bee that is feasting on the flower in the main anatomical panel gets a shower of the pesticides through the overlap of the panels. The strawberry plant then reaches into other thickener panels as the eye trails further down, connecting among other things to a swarm of wild pollinators of different species to the left and a sunny sky over workers picking strawberries in the bottom right corner. New poetic and associative meanings arise out of the collision of all the images and their different concepts and emotions – the creepiness of the crop sprayer’s almost skull-looking mask and strange protective gear contrasts with the intimate close-up of the loving and joyful meeting between flower and insect and the bumblebee leaping out of the sun-drenched field where a strawberry harvest is taking place in the bottom right corner. The monstrous and ghostly coexist through this overlap. The images do not form a set narrative with a clear reading order through standing together in this way. The bee exists in several places and times at once; it is in the crop-sprayer’s field, getting killed by poison, but is also buzzing, feasting and bursting with life in other realities/facets of plant–pollinator–human relationships. Poetic comics allow for thickening by offering several different readings and potential meanings simultaneously.