Figures & data

Figure 1. Factors affecting the therapeutic decision in children with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Table 1. Selection of possible differential diagnoses of epiphora due to congenital dacryostenosis (modified from [9]).

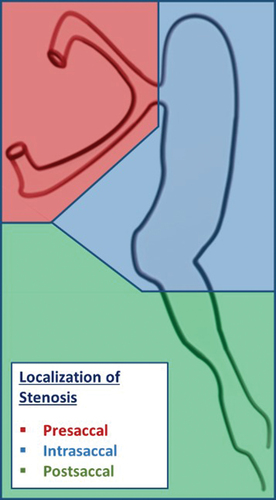

Table 2. Classification of lacrimal stenosis.

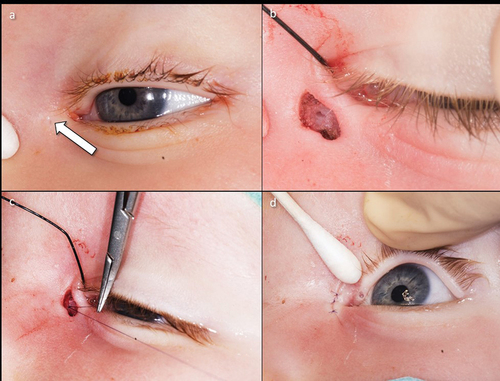

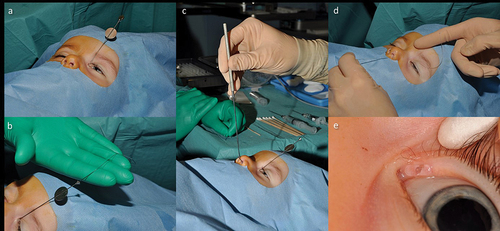

Figure 4. Lacrimal fistula and its surgical treatment.

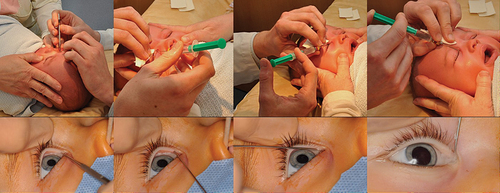

Figure 5. Lacrimal probing and syringing under local anesthesia (upper row) and general anesthesia (lower row).

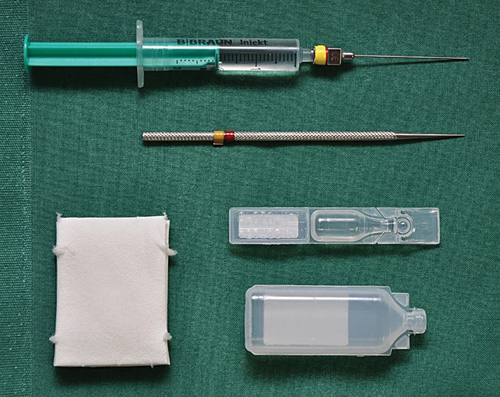

Figure 6. Instruments and materials for lacrimal syringing (glucose 40% solution, sponges, local anesthetic eye drops, probe for dilatation, syringe with Bangerter’s cannula and saline solution).

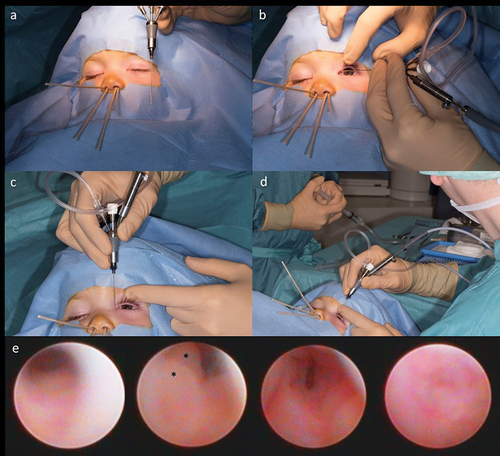

Figure 7. Monocanaliculonasal intubation in an 18-month-old child (left eye).

Figure 8. Dacryoendoscopy in a 14-month-old child (left eye).

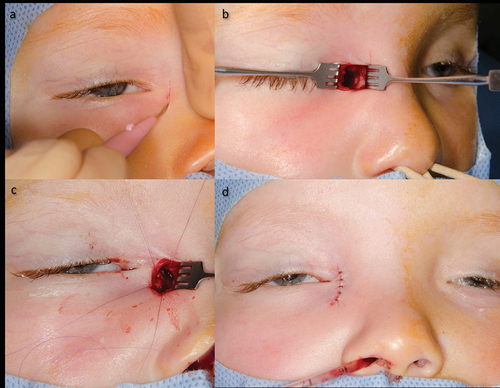

Figure 9. Transcutaneous dacryocystorhinostomy.

Table 3. Staged therapeutic concept for Congenital Dacryostenosis [12].