Figures & data

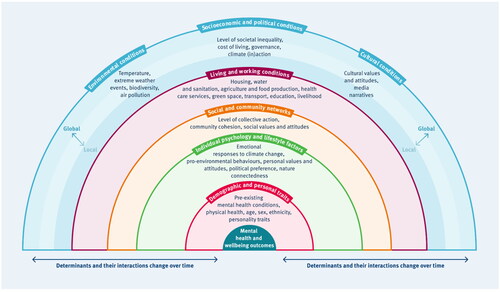

Figure 1. Framework for the determinants of mental health and wellbeing. The framework contains nested layers of determinant categories that all interactively influence each other and ultimately the mental health and wellbeing of an individual. The determinants, their interactions, and their influence on mental health and wellbeing changes over time. Changes over time include: changes across the lifecourse, increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, exposure to multiple climate impacts, and the time since the climate impact occurred. Adapted from Dahlgren and Whitehead’s model, with influences from Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory and the Lancet Commission for Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development (Citation9,Citation52,Citation53). The framework is designed to be illustrative and encourage 'systems-thinking', but not to be exhaustive.

Figure 2. Key near term (to 2040) risks to physical, biological, human and managed systems resulting from climate change across different regions of the world. Risks include disruption to infrastructure, livelihoods and incomes due to increased extreme climate and weather events and impacts on health - including mental health - due to increased temperature. Adapted from content in Figure SPM.8 of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report Summary for Policymakers (2014) (Citation56) and Figure SPM.3 of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Working Group II Report on Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (2022) (Citation57). Risks presented here are illustrative and not exhaustive.

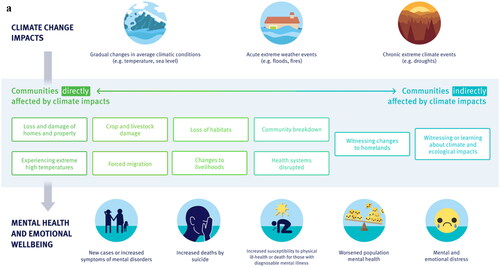

Figure 3a. Examples of the continuum of impacts that climate change has on mental health outcomes. Climate change impacts (top row of circles) including rising temperatures and sea level, and extreme weather events such as floods or droughts, effect mental health and emotional wellbeing (bottom row of circles) including: new cases or increased symptoms of mental disorders; increased deaths by suicide; increased susceptibility to physical illness or death for those who meet the criteria for mental disorders; worsened population mental health, and mental and emotional distress. This occurs directly and indirectly via a variety of pathways represented here as a continuum, from direct experiences (left hand side of shaded box), for example of extreme high temperatures or home loss in a wildfire, to indirect experiences of climate impacts (right hand side of shaded box), for example by reading about such events in the media and hearing about insufficient climate action from leaders.

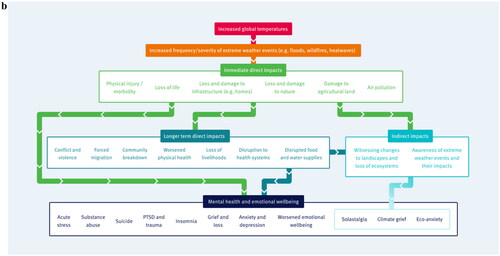

Figure 3b. An illustration of the multiple pathways (some more direct and some more indirect) by which a single example of a climate change-related event - e.g. a more severe wildfire - can ultimately worsen mental health and emotional wellbeing.

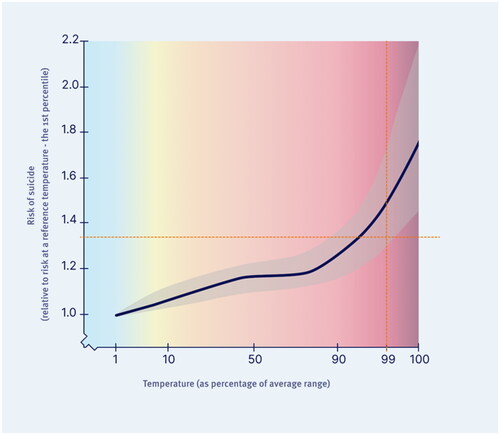

Figure 4. Modelled Relative Risk of suicide in the UK increases with increasing temperature, estimated using a conditional Poisson model that was adjusted for long-term time trend, season and day of the week. Relative Risk is the risk of suicide relative to the risk at the lowest suicide risk temperature. Adapted from Kim et al. 2019 (90).

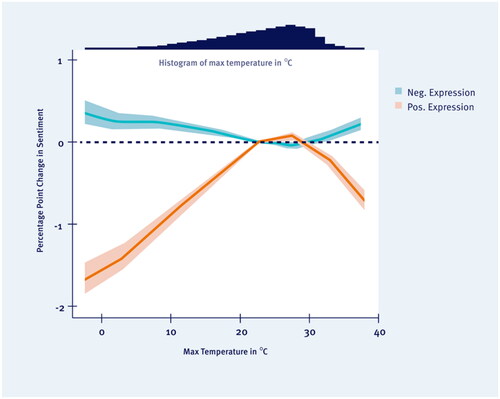

Figure 5. The relationship between daily maximum temperatures and the rates of expressed sentiment of approximately 2.4 billion Facebook status updates from 2009-2012. The relationship was produced by aggregating the facebook status updates to the city level of the 75 most populated metropolitan areas in the USA, and modelling the influence of maximum daily temperature on quantified sentiment (positive or negative) expressed in the status update. Other confounding variables were also considered. Sentiment is more negative at very low or very high temperatures. Adapted from Baylis et al., 2018 (128).

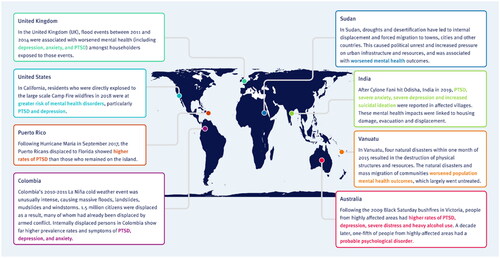

Figure 6. Examples of the impact of extreme weather events on mental health across the world, including the United Kingdom (Citation200–202), United States of America (Citation203), Puerto Rico (Citation204–207), Colombia (Citation208), Sudan (Citation208), India (Citation209), Vanuatu (Citation208), Australia (Citation210).

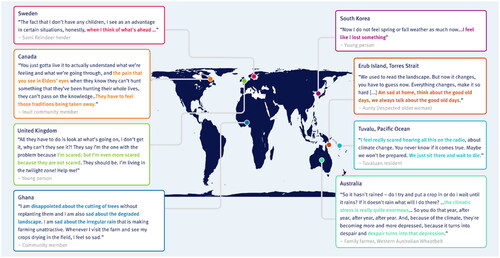

Figure 7. Example quotes from studies examining psychological and emotional impacts of climate crisis awareness or witnessing climate impacts, from Sweden (Citation366), Canada (Citation367), the United Kingdom (Citation368), Ghana (Citation369), South Korea (Citation370), the Torres Strait (Citation371), Tuvalu (Citation361) and Australia (Citation165).

Table 1. Some examples of interventions and support for mental health and wellbeing impacts of climate change

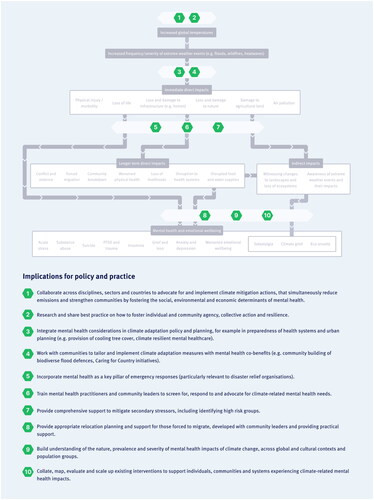

Figure 8. Illustrative intervening actions taken at each point of the pathways by which an extreme climate event impacts mental health, as originally considered in . Action at 'upstream' or earlier points can mitigate against 'downstream' impacts, though action and support is needed at all levels.

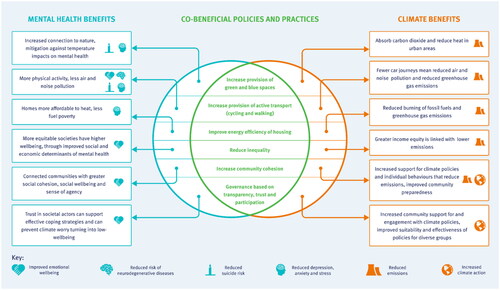

Figure 9. Illustrative examples of co-beneficial policies and practices that can deliver benefits for both mental health and the climate. This includes provision of green and blue spaces and active transport, improving energy efficiency of housing, reducing inequity across and within societies, increasing community cohesion and governance based on transparency, trust and participation (Citation2,Citation308,Citation462,Citation466,Citation497,Citation498,Citation508).