Figures & data

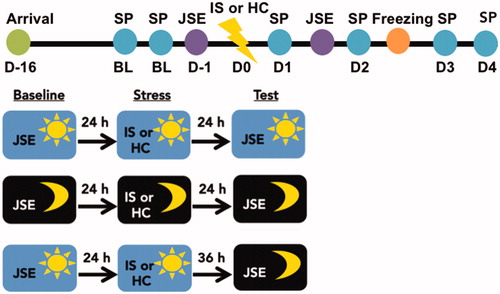

Figure 1. Timeline for experiment 1. Rats acclimated to the facility for two weeks after arrival. Rats underwent baseline testing in sucrose preference (SP) and juvenile social exploration (JSE) tests on the 2 days prior to stress. On experimental Day 0 (D0) rats underwent 100 inescapable tailshocks (inescapable stress; IS) or home cage (HC) control treatment either during the middle of the dark phase or middle of the light phase. Rats were subsequently tested on the SP, JSE and shock-elicited freezing tests.

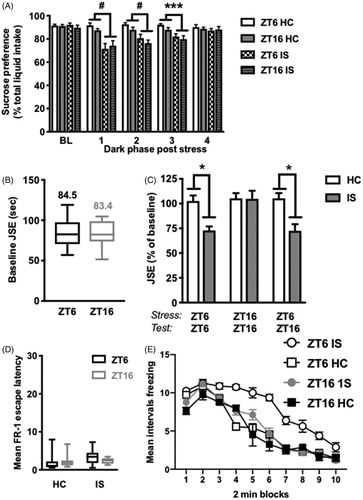

Figure 2. Stress-induced behavioral changes in juvenile social exploration and shock-elicited freezing, but not sucrose preference, are modulated by time of stressor exposure. Rats received IS or no stress (HC) at ZT6 or ZT16 followed by behavioral testing. (A) Sucrose preference testing occurred during the first 4 h of the dark phase on the two days prior to stress (average baseline, BL) and each of four days after stress (B-C) Juvenile social exploration testing occurred 24 h or 36 h following stress. The ZT6-ZT6 group was stressed at ZT6 and tested 24 h later at ZT6; the ZT16-ZT16 group was stressed at ZT16 and tested 24 h later at ZT16; and the ZT6-ZT16 group was stressed at ZT6 and tested 36 h later at ZT16 (D-E) Fear testing as measured by shock elicited freezing in the shuttlebox occurred 48 h after stress (D) Mean FR-1 escape latencies for FR-1 trials (E) Mean intervals freezing, in 2 min blocks, immediately following two FR-1 trials in a shuttlebox. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001, #p ≤ .0001.

Table 1. PCR primer sequences for 5-HT system genes.

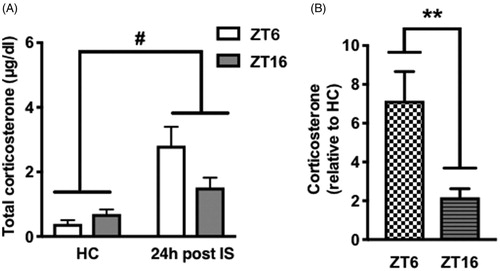

Figure 3. Basal CORT concentrations 24 h after stress during the light or dark phase. Rats received IS or no stress (HC) at ZT6 or ZT16 and were sacrificed 24 h later. (A) Absolute serum CORT concentrations (B) Fold increase in CORT concentrations relative to HC. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p ≤ .01, #p ≤ .0001.

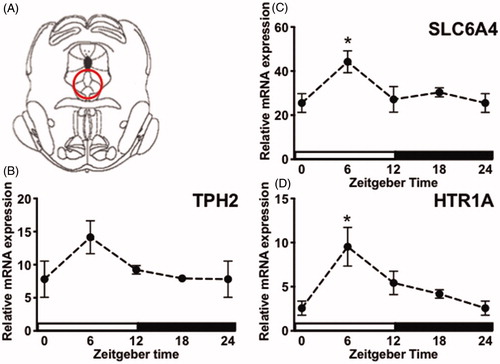

Figure 4. Circadian gene expression of DRN 5-HT factors. (A) Digital template reproduced from the rat brain atlas (Paxinos & Watson, Citation2007) denoting the location of DRN micropunch (circled area). Tissue was collected from stress-naïve rats every 6 h across the light-dark cycle. (B-D) TPH2, SLC6A4, and 5-HT1AR mRNA concentrations are expressed relative to housekeeping gene β-actin and presented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ .05.

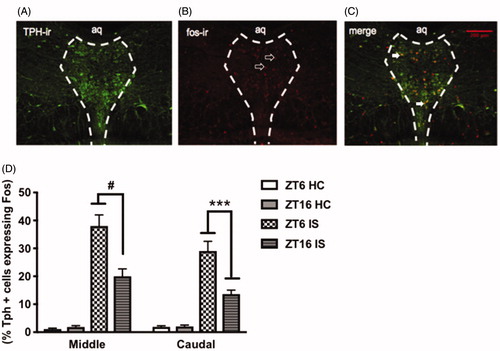

Figure 5. Stress-induced activation of DRN 5-HT neurons is modulated by time of day. Representative image of stressed-induced activation of DRN 5-HT neurons at ZT6 (A) TPH-immunoreactive (ir) neurons (green) (B) fos-ir nuclei (red) (C) Tph-positive neurons expressing fos in the middle and caudal aspects of the DRN. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. ***p ≤ .001, #p ≤ .0001.