Figures & data

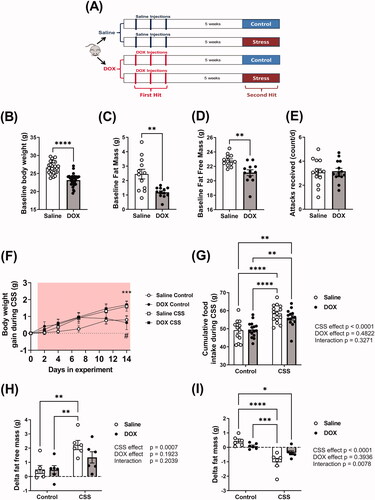

Figure 1. Effect of juvenile exposure to DOX, adult-onset CSS, and their combination on body composition. (A) Experimental design of the two-hit model of latent DOX-induced cardiotoxicity using CSS as a second hit. Male 5-week-old C57BL/6N mice were administered DOX (4 mg/kg/week) or saline for 3 weeks and allowed to recover for 5 weeks prior to exposure to 14 d of CSS. Effect of juvenile exposure to DOX one day prior to CSS on (B) body weight (n = 27–29 per group), (C) Fat mass (n = 12 per group), and (D) fat free mass (n = 12 per group). (E) Average number of attacks received during the daily social defeat interactions in CSS (n = 14). Comparisons between the two groups in (B–E) were performed using unpaired student t-test. (F) Daily body weight gain during CSS where a significant stress × time interaction is found (F(4,208)=5.915, p<.001) and asterisks denote significant binary differences within each time point among groups following Tukey’s HSD post hoc test. (#p=.054301, within saline groups, control vs. CSS; ***p<.001, within DOX groups, control vs. CSS; comparisons at day 14), (G) Total amount of food consumed in the course of CSS (n = 13–15 per group). (H) Delta fat free mass (n = 6 per group), and (I) Delta fat mass (n = 6 per group) following CSS. Values are represented as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests as appropriate (*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, ****p<.0001). Detailed statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1. Echocardiography-derived morphometry parameters after CSS in male C57BL/6N mice pre-exposed to DOX as juveniles. Values are presented as mean ± standard of the mean (SEM).

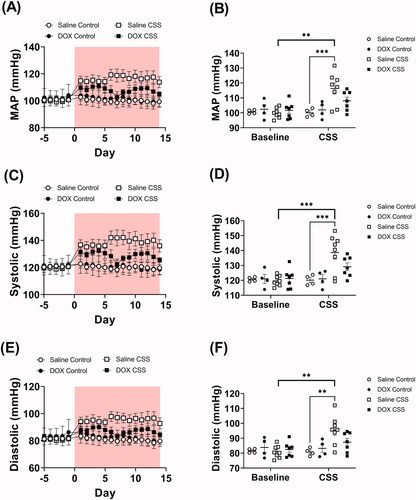

Figure 2. Juvenile exposure to DOX prevented CSS-induced hypertension. Male 5-week-old C57BL/6N mice were administered DOX (4 mg/kg/week) or saline for 3 weeks and allowed to recover for 5 weeks prior to exposure to CSS. Average daily values and average values at baseline and at the end of CSS of (A and B) Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), (C and D) systolic, and (E and F) diastolic blood pressure recorded by radio telemetry prior to and over the course of CSS (n = 4–8 per group); shaded area on the graphs represents time during CSS protocol. Values are represented as means ± SEM. Statistical analysis was conducted by repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests (**p<.01, ***p<.001). Detailed statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

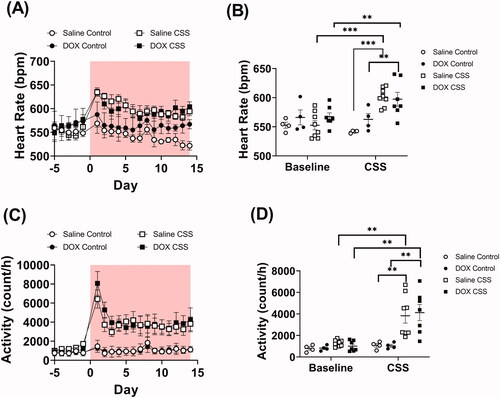

Figure 3. Adult CSS induces tachycardia and increases activity level. Male 5-week-old C57BL/6N mice were administered DOX (4 mg/kg/week) or saline for 3 weeks and allowed to recover for 5 weeks prior to exposure to CSS. Heart rate and locomotor activity data were recorded by radio telemetry. Time course and average values at baseline and at the end of CSS of (A and B) heart rate and (C and D) locomotor activity prior to and during CSS (n = 4–8 per group); shaded area on the graphs represents time during CSS protocol. Values are represented as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted by repeated measures ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests(**p<.01, ***p<.001). Detailed statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 3.

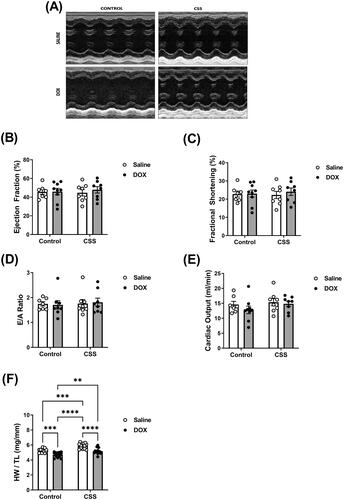

Figure 4. Juvenile exposure to DOX abrogated CSS-induced hypertrophy without changes in cardiac function. Male 5-week-old C57BL/6N mice were administered DOX (4 mg/kg/week) or saline for 3 weeks and allowed to recover for 5 weeks prior to exposure to CSS. Cardiac function was assessed by trans-thoracic echocardiography (n = 7–9 per group) at the end of CSS. (A) Representative M-Mode images from parasternal short axis view of the heart, (B) ejection fraction, (C) fractional shortening, (D) E/A ratio, and (E) cardiac output. (F) Heart weight to tibia length ratio (HW/TL) (n = 13–15 per group). Values are represented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance of pairwise comparisons was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests (**p<.01, ***p<.001, ****p<.0001). Detailed statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 4.

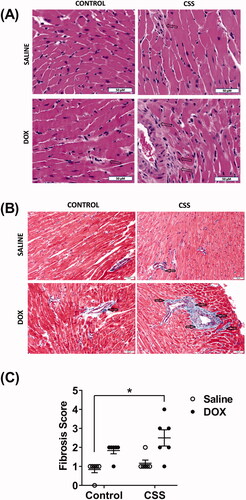

Figure 5. Histopathologic evaluation of myocardial fibrosis and inflammation in hearts from male C57BL/6N mice. Male 5-week old C57BL/6N mice were administered DOX (4 mg/kg/week) or saline for 3 weeks and allowed to recover for 5 weeks prior to exposure to CSS. Representative images from (A) hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and (B) Masson’s trichrome stained heart sections; bar scale = 50 µM. Inflammatory cell infiltration in (A) and fibrotic areas in (B) are indicated with arrows. (C) Semi-quantification of fibrosis score derived from Masson’s trichrome stain (n = 6 per group). Statistical analysis was determined by non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis followed by a Mann–Whitney tests (*p< .05).

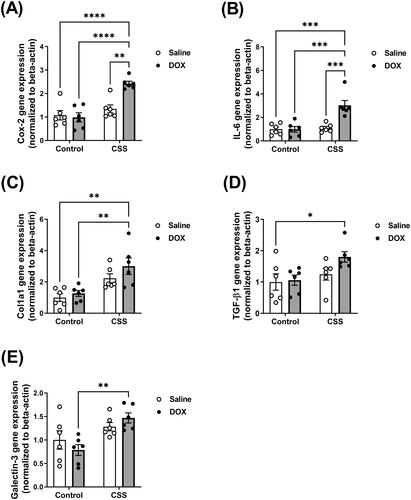

Figure 6. Inflammatory and fibrotic markers are upregulated following CSS in DOX-exposed mice. Male 5-week old C57BL/6N mice were administered DOX (4 mg/kg/week) or saline for 3 weeks and allowed to recover for 5 weeks prior to exposure to CSS. The mRNA expression of inflammatory markers (A) Cyclooxygenase-2 (Cox-2) and (B) Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and the fibrotic markers (C) Collagen 1a1 (Col1a1), (D) Transforming Growth Factor-beta-1 (TGF-beta1), and (E) Galectin-3 was determined by real-time PCR (n = 6 per group). Values are represented as means ± SEM. Statistical significance of pairwise comparisons was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post-hoc tests (*p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001, ****p<.0001). Detailed statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (150.1 KB)Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the methods and/or supplementary material of this article.