Figures & data

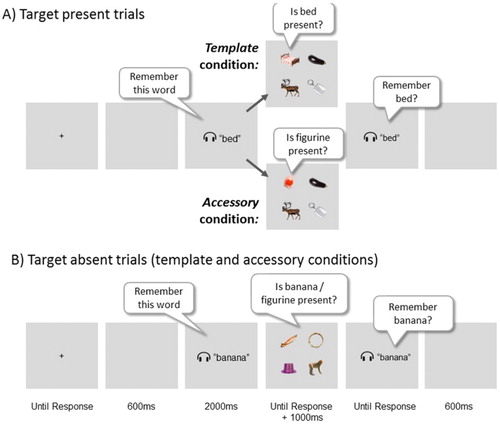

Figure 1. Illustration of the procedure and different trial types, with various stimulus examples. On all trials, participants memorized a spoken word for a verbal recognition test at the end of the trial. During the retention period, they performed a visual search task. Panel A) illustrates target present trials, where in the template condition, people searched for the object referred to by the word, while in the accessory condition, the word was not relevant for the search, but was still needed for the memory test. Here, observers searched for a member of a set of plastic figurines instead. The crucial trials were the target absent trials, illustrated in Panel B). These contained an object that was semantically related (in this example the monkey), an object that was visually related (here the canoe) and two objects that were unrelated (here the hat and the tambourine) to the memorized word. In terms of stimulus sequence, these trials were identical for both template and accessory conditions. However, as for the present trials, the task set differed per block, as in the template condition observers were searching for the spoken word, while in the accessory condition they were searching for a figurine, while still remembering the word for the memory test.

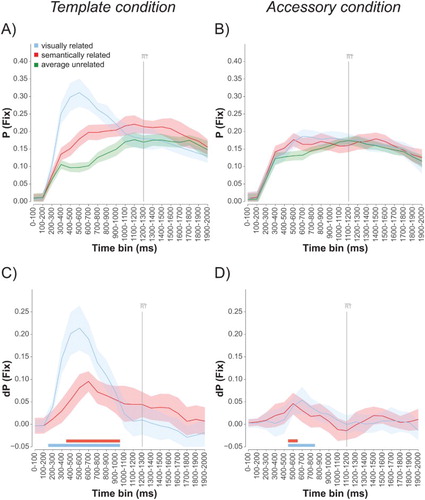

Figure 2. Target absent trials. The proportion fixation time, P(fix), towards visually related, semantically related, and unrelated objects for every 100 ms time bin for the template (A) and the accessory (B) condition and the difference in proportion fixation time, dP(fix), for the semantically and visually related objects relative to the average of the unrelated objects (C for template condition and D for the accessory condition). The grey vertical lines mark the average search times for each condition. Error bars reflect 95% confidence intervals (two-tailed) for within-participants designs (Cousineau, Citation2005; Morey, Citation2008). The red and blue horizontal bars mark the bins for which there was a significant semantic (red) and visual (blue) bias as indicated by t-tests for each bin, corrected for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction (correcting for the number of bins up to the one including the response, i.e., α = 0.05/13).

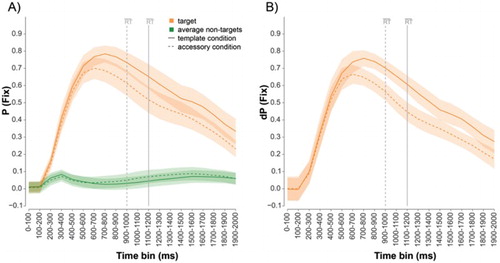

Figure 3. Target present trials. A) The proportion fixation time, P(fix), towards the target and the average of the non-targets for every 100 ms time bin. B) The difference scores, dP(fix), for the target relative to the average of the non-targets. The template condition is indicated with a solid line, whereas the accessory condition is indicated with a dotted line. The grey vertical lines mark the average search times for each condition. Error bars reflect 95% confidence intervals (two-tailed) for within-participants designs (Cousineau, Citation2005; Morey, Citation2008).