Figures & data

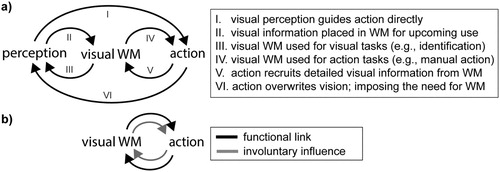

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of routes and influences between vision, visual working memory, and action. (a) Visual working memory here refers to the retention and manipulation of detailed visual information, such as shape and colour. Action refers to overt actions, including eye and hand movements, and encompasses action planning. Working memory is situated at the interface between past vision and future action; when direct route “I” is not feasible because relevant visual information has meanwhile disappeared from sight. Popular laboratory tasks of visual working memory have focused predominantly on route “III”, while research on perception and action has focused mostly on route “I”. This review focuses on routes “IV” and “V”. Route “VI” reminds us that our own actions are often the cause of why we need to rely on visual working memory (when our own movements render visual information “out of sight”). (b) This review is centred on concepts and insights gained from functional and involuntary links between visual working memory and (planned) action. “WM” stands for “working memory”; “perception” refers to “visual perception” within the context of this review.

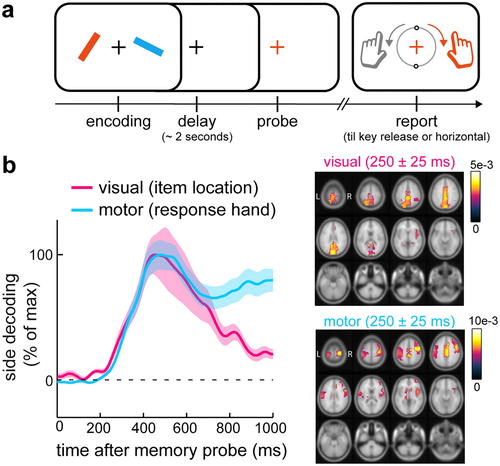

Figure 2. Visual-motor working memory task reveals concurrent accessibility of visual representation and action plans for working-memory guided behaviour. (a) Visual-motor working memory task in which visual shape (orientation) information is linked to specific prospective manual actions (predictable reproduction report) after a memory delay. In this task, actions rely on detailed visual representations from memory. Item locations and prospective response hands (linked to orientation) are independently manipulated to enable independent tracking of visual and motor memory attributes in the EEG. (b) Empirical evidence (EEG decoding) from this task for concurrent selection of visual representations and their associated manual actions from working memory. This data suggest that multiple visual items in memory are held available for selection together with plans for the multiple potential actions they afford. Adapted from (van Ede et al., Citation2019b).