Figures & data

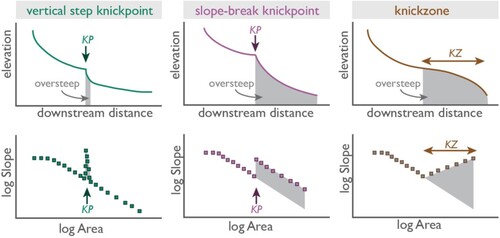

Figure 1. Anomalous river geometries in long profiles (top) and slope-area diagrams (bottom). Modified after Neely et al. (Citation2017), Haviv et al. (Citation2010), Bishop et al. (Citation2005). Gray shaded areas indicate steepened river reaches. Abbreviations: KZ – knickzone; KP – knickpoint.

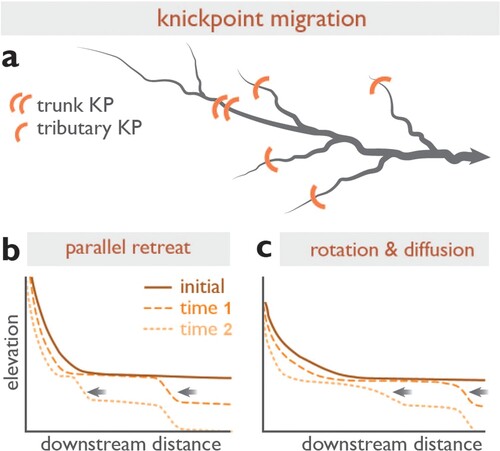

Figure 2. Knickpoint migration and evolution. (A) Example of knickpoint migration in map view, where rate of upstream knickpoint propagation is correlated to A, the upstream drainage area (where area ≈ discharge). Long profile views of knickpoint migration and evolution over time, following classical stream-power-law predictions: (B) maintenance of knickpoint form by parallel retreat and (C) knickpoint retreat with rotation and diffusion of knickpoint form (Howard et al., Citation1994; Whipple & Tucker, Citation1999). Modified from Bishop et al. (Citation2005); Castillo et al. (Citation2013); Howard et al. (Citation1994).

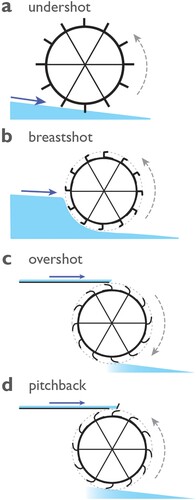

Figure 3. (A – D) Types of vertical waterwheel, modified after Shaw (Citation1984). All wheels, except the overshot wheel (C), rotate anticlockwise. In the overshot (C) and pitchback (D) wheels, a launder delivers water to top of the wheel.

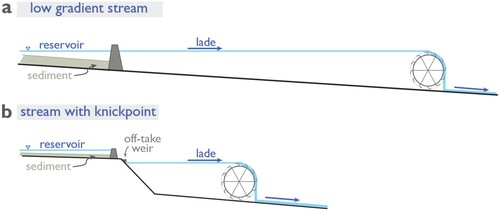

Figure 4. Schematic diagrams of river long profile, mill dam, lade and wheel for a (A) low gradient stream and (B) a stream with a knickpoint. Note that the lower gradient stream requires a larger dam and a longer lade to deliver the water to the top of the waterwheel. Modified from Bishop and Muñoz-Salinas (Citation2013).

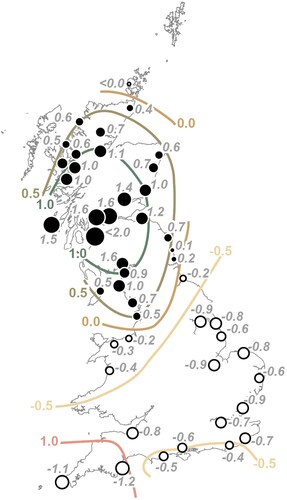

Figure 5. Relative land-/sea-level changes (mm yr−1) since 4000 cal yr BP. Positive values indicate relative land uplift and sea-level fall (Scotland) and relative land subsidence and sea-level rise (southern England). Modified from Shennan and Horton (Citation2002). Contours are drawn after data.

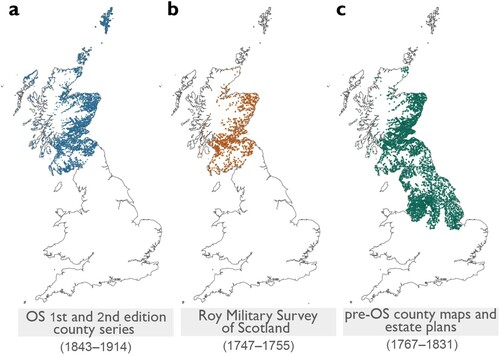

Figure 6. Over 20,000 observations of mills in Scotland and northern England from historic maps held by the National Library of Scotland digital archive. (A) Mill locations from Ordnance Survey (OS) 1st and 2nd edition county series maps of Scotland (1843–1914) and HES database as part of the Scottish Water Mills Project; (B) Mill locations queried from the Roy Gazetteer of the Roy Miliary Survey of Scotland (1747–1755); and (C) Mill locations from pre-OS county maps and estate plans (1767–1831) for Scotland and select counties of northern England. Mapping in (B) and (C) is ongoing and part of the ‘Away from the Water’ project (T. Jonell, pers. comm.).

Data availability statement

Historical mill data from 1843–1914 mentioned in this work are available through the National Library of Scotland ‘Scottish Water Mills Project’ website (https://maps.nls.uk/projects/mills/index.html). Data from 1747–1831 are derived from maps held in the public domain: through the collaborative Roy Gazetteer project between the National Library of Scotland and British Library (https://maps.nls.uk/roy/) and from county maps held by the National Library of Scotland (https://maps.nls.uk/counties/), the Digital Archive at McMaster University Library (http://digitalarchive.mcmaster.ca/), and the Yale University Library (https://library.yale.edu/). Data associated with the ‘Away from the Water’ project are available upon request from the corresponding author.