Figures & data

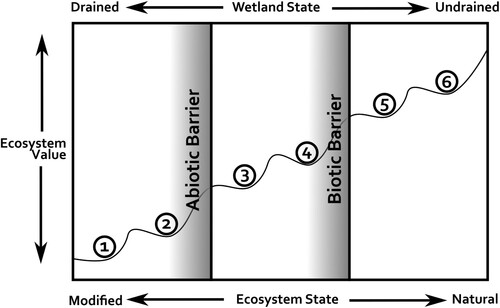

Figure 1. The naturalness axis in biodiversity conservation favours wetlands which are apparently unmodified by drainage. States 1 and 2 represent the range of wetlands impacted by drainage and other physical changes (e.g. eutrophication) which restoration would aim to remove. States 3 and 4 represent wetlands which have been impacted by perceived negative changes in biodiversity (e.g. invasive species). States 5 and 6 represent functional and ‘natural’ wetlands – the most highly valued positions. Wetland restoration aims to move any particular wetland towards higher states. Generalised scheme developed by Hobbs & Harris (Citation2001) (but see also, Machado Citation2004), image adapted from Keenleyside et al. (Citation2012, 6).

Table 1. Various forms of ‘natural’ appear in legislative and policy frameworks that guide the designation, management and restoration of wetland Protected Areas. This has been a defining force of ecological conservation for more than 50 years.

Table 2. Habitat definitions for SSSI features identified and used in this analysis. Compiled from Ratcliff Citation1977; Palmer, Bell, and Butterfield Citation1992; Mainstone et al. Citation2018.

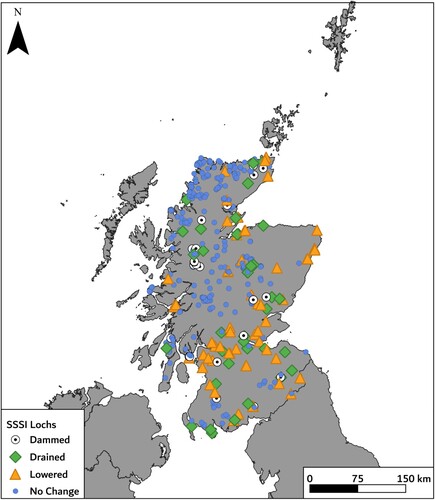

Figure 2. Lochs depicted on the Roy Military Survey of Scotland (1747–1755) now designated as wetland SSSIs.

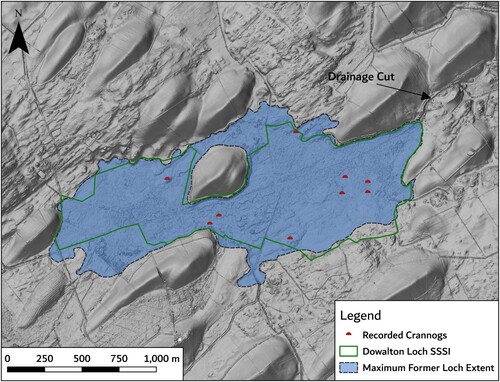

Figure 3. Lidar Composite Digital Terrain Model Scotland (Phase 3) 50 cm resolution hillshaded with modelled former maximum extent of Dowalton Loch at (c. 43 m OD) and current extent of Dowalton Loch SSSI. © Open Government Licence, accessed from EDINA Digimap service.

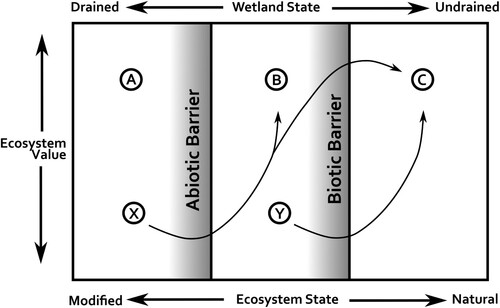

Figure 4. A novel ecosystems perspective on wetland value revising . Heavily modified ecosystems can be highly valued (State A). Notably, there is no longer a single axis upon which any particular wetland can slide up or down. Restoration is represented by the sinuous arrows with restoration choosing to move ecosystems to higher valued positions (usually restoration targets ecosystems like X and Y with a goal of achieving states B and C). This framework also provides a blueprint for identifying where and what wetland archaeological perspective is useful as well as helping avoid conflict between wetland restoration and wetland archaeology preservation. Movement across abiotic barriers should include wetland archaeological analysis of drainage to improve the restoration programme while also identifying and avoiding conflicts with preservation of archaeology possibly at risk. Movement across biotic barriers could use wetland archaeology as an archive of past states if necessary to achieve higher value states.

Supplemental Material

Download Comma-Separated Values File (36.7 KB)Data availability statement

The Roy Military Survey of Scotland data used in this paper is available in Stratigos (Citation2016a) <https://doi.org/10.1080/14732971.2016.1248129>. Data on habitat and condition for Scottish Sites of Special Scientific Interest are available from <https://sitelink.nature.scot/home> and boundary data for Scottish Sites of Special Scientific Interest are available from<https://gateway.snh.gov.uk/natural-spaces>.