Figures & data

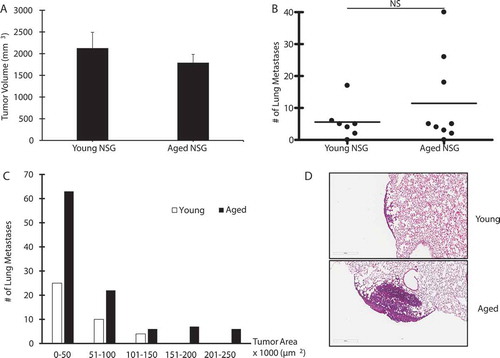

Figure 1. Aging is associated with increased lung metastases

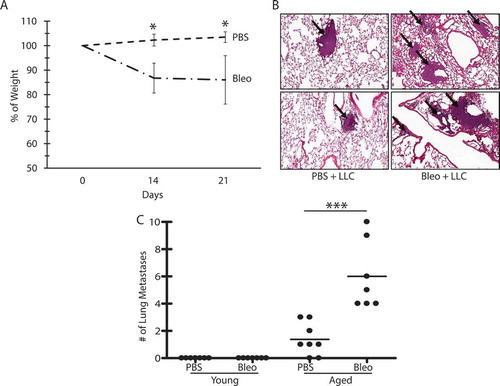

Figure 2. Bleomycin treatment is associated with increased metastases, but only in aged lungs

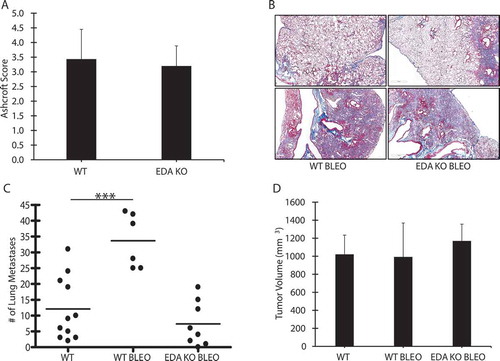

Figure 3. Fibronectin EDA is dispensable for aged-related lung cancer progression

Figure 4. Fibronectin EDA is required for bleomycin-induced augmentation of metastasis

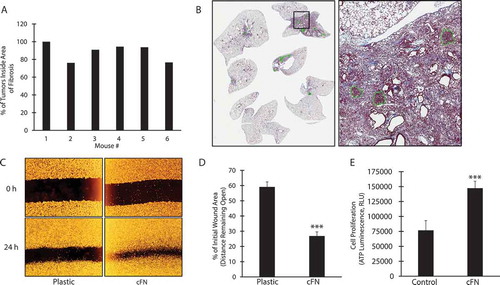

Figure 5. Lung metastases develop primarily in fibrotic areas

Figure 6. Effect of Immunity on Lung Cancer Progression