Figures & data

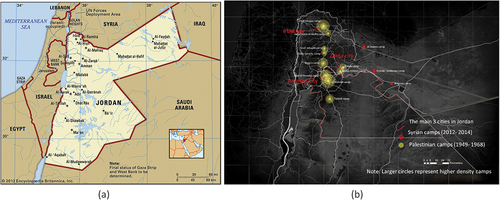

Figure 1. (a) Jordan is situated between politically conflicted areas, making it a main refugee zone. Source (Britannica Encyclopaedia, 2012). (b) Graphical representation of camps locations and densities of camps in Jordan, 2021–2022. Larger circles indicate higher density camps. Author’s map. Generated using Open Street data in ArcGIS Pro.

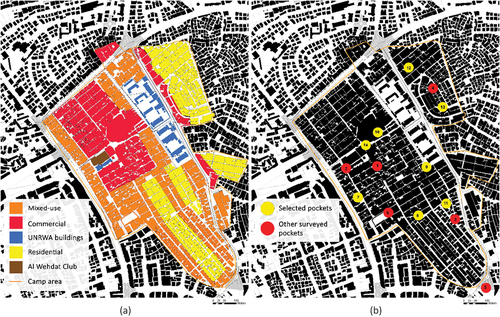

Figure 2. (a) The built-up area map was created using satellite imagery mapping in ArcGIS Pro, while zoning was based on the Department of Palestinian Affairs’ plot distribution map, which is publicly accessible. (b) mapping of potential pocket spaces.

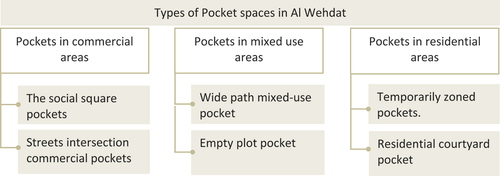

Table 1. Pocket space characteristics analysis.

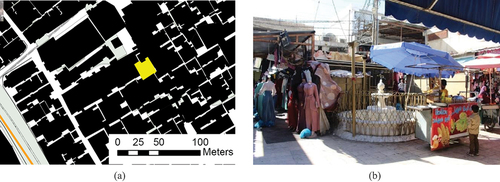

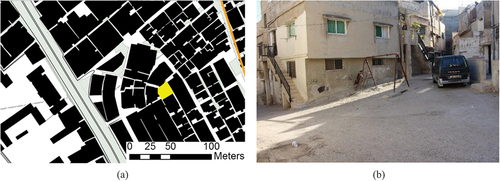

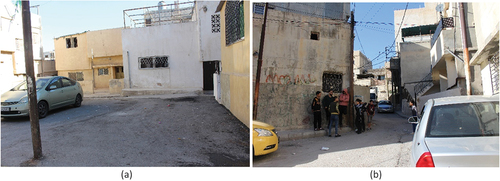

Figure 4. (a) An example of social square pocket (pocket number 1). (b) An example of street intersection commercial pocket (pocket number 10).

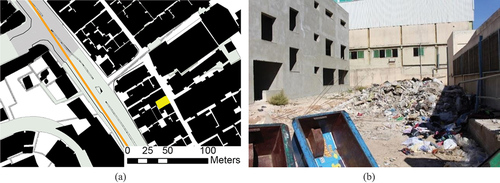

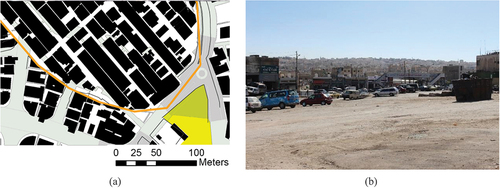

Figure 5. Pocket spaces in residential areas, (a) Residential courtyard pocket (pocket 12 in ), (b) Temporarily zoned pocket (pocket 4 in ).

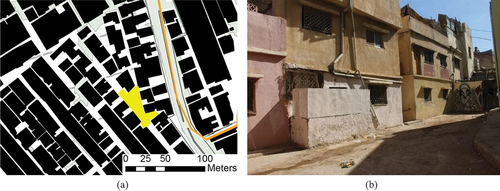

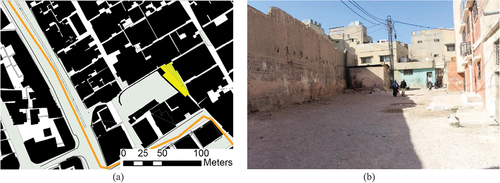

Figure 6. Examples of pocket spaces in mixed-use areas. (a) Wide path pocket space (pocket 9). (b) Empty plot (pocket 5).

Table 2. Example of how the decision matrix was used to assess the potential of each pocket for revitalization, based on the observations in .

Figure 7. Al Mutamaizoon team small scale greening and painting dilapidated houses to improve the neighbourhood aesthetics. Images are courtesy of Rania Alkouz.

Figure 8. Al Mutamaizoon team painting Palestinian and Jordanian landmarks. (a) displays the phrase ‘’We will return’’ on a Palestinian landmark. (b) shows Palestinian traditional patterns with the ‘’Palestine’’ written on one of the residence homes. It also shows a painting of a woman wearing a Palestinian traditional dress and carrying a water jug on her head- a common task carried out by women in rural areas of Palestine in the past (c) shows the Roman columns in Jerash, a landmark in Jordan, which symbolise harmony with their host country.

Table 3. Summary of the community perspective on the opportunities and challenges facing the revitalization of pocket public spaces in Al Wehdat refugee camp.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (22.9 KB)Data availability statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within this article as supplementary appendices. These appendices provide detailed information on the following:

Appendix A – Pocket Selection (Decision Matrix): This appendix presents the detailed decision matrix used to evaluate and select pockets for analysis. It includes criteria, scoring, and comments for each pocket, providing transparency into the pocket selection process.

Appendix B – Samples of Thematic Analysis: This appendix offers a selection of thematic analysis samples, including verbatim excerpts from interviews or textual data. These samples illustrate the emergence of key themes and support the qualitative findings discussed in the manuscript.