Figures & data

Table 1. Sequences of primers used in real-time polymerase chain reaction (real-time PCR).

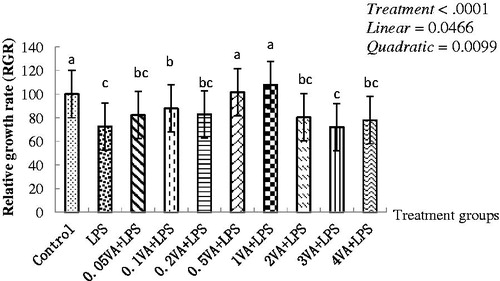

Figure 1. Effect of VA on LPS-induced BMECs proliferation. Bovine mammary epithelial cells (BMECs) were randomly divided into 10 groups with six replicates. The first group was used as a control: without vitamin A (VA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 30 h. Group 2 was the LPS-treated group: without VA for 24 h before treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) alone for an additional 6 h. Groups 3–10 were eight doses of VA plus LPS-treated groups: pre-treated BMECs with 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 μg/mL of VA for 24 h and then incubated in the presence of 1 μg/mL of LPS and VA for a further 6 h. The cell proliferation was evaluated by methyl thiazolyl tetrazo-lium (MTT) cytotoxicity assay. Values are means with their standard deviations depicted by vertical bars (from triplicate experiments). a–cMeans in the treatment groups not followed by the same letter differ significantly (p<.05) whereas the differences were considered to be a statistical trend when .05<p<.10.

Table 2. Effect of VA on the antioxidant enzyme activity and inflammatory cytokines content in BMECs upon LPS damageTable Footnotea.

Table 3. Effect of VA on the gene expression of selenoprotein, inflammatory cytokines, Nrf2, and NF-κB pathway of BMECs upon LPS damageTable Footnotea.

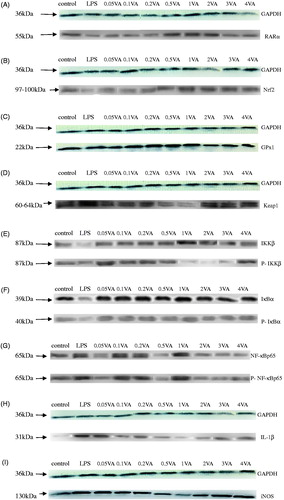

Figure 2. Effect of VA on LPS-induced selenoproteins, RARα, IL-1β protein expression, and phosphorylation of Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways in BMECs. The cells were randomly divided into 10 groups with six replicates. The first group was used as control: without vitamin A (VA) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 h. Group 2 was the LPS-treated group: without VA for 24 h before treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for an additional 6 h. Groups 3–10 were eight doses of VA plus LPS treated groups: pre-treated bovine mammary epithelial cells (BMECs) with 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, or 4 μg/mL of VA for 24 h and then incubated in the presence of 1 μg/mL of LPS and VA for a further 6 h. Expressions of retinoic acid receptor α (RARα) (A), nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) (B), glutathione peroxidase1 (GPx1) (C), Kelch-like ECH2 associated protein 1 (Keap1) (D), interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (H), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (I), and phosphorylated IκB kinase β (P-IKKβ) (E), inhibition kappa-B α (P-IκBα) (F), nuclear factor kappa-Bp65 (P-NF-κBp65) (G) protein levels were detected by Western blotting and normalised to glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) levels.

Table 4. Effect of VA on LPS-induced selenoproteins, RARα, IL-1β protein expression, and phosphorylation of Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways in BMECsTable Footnotea.