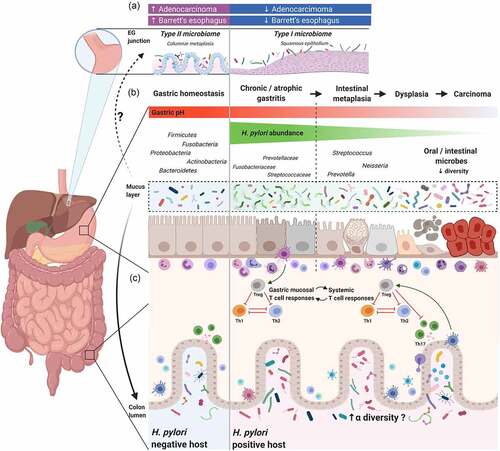

(A) Case-control and epidemiology studies demonstrated

H. pylori infection is inversely associated with Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Studies suggest that the healthy esophagus is associated with a Type I microbiome, which is dominated by

Streptococcus, while Barrett’s esophagus is associated with a Type II microbiome, containing a lower relative abundance of

Streptococcus and a greater proportion of Gram-negative bacteria. Whether

H. pylori directly or indirectly influences the esophageal microbiome, and the relationship between

H. pylori, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, and the esophageal microbiome still needs to be elucidated. (B) Schematic plot presentation of the influence of

H. pylori on gastric and colonic microbiota. In healthy, non-inflamed mucosa, the gastric mucosa comprises a thick layer of mucus, which serves as a protective barrier and as a highly diverse, specialized niche for colonization of gastric microbiota. In

H. pylori–positive patients with chronic (atrophic) gastritis,

Helicobacter dominates the gastric mucosa, resulting in reduced microbial diversity. Other bacteria, like Streptococcaceae, Fusobacteriaceae, and Prevotellaceae, may be present to a lesser extent. After a long period of co-infection and co-colonization, combined with the presence of risk factors that determine the gastric dysbiotic parietal cell loss with an increase in pH, the innate immune response and gastric microbiota interactions promote the progression of pre-neoplastic lesions. In the later stages of carcinogenesis, ranging from intestinal metaplasia to gastric adenocarcinoma, a reduction or depletion of

H. pylori is seen in the gastric mucosa. In gastric cancer, microbial diversity is reduced, and oral or intestinal-type bacteria are enriched. (C) In chronic

H. pylori infections, the

H. pylori–experienced dendritic cells retain a semi-mature phenotype and induce immunosuppressive regulatory T cell (Treg) differentiation, rather than Th1 or Th17 cells from naive Th0 cells.

Citation93,Citation136,Citation137 Tregs produced in the gastric mucosa are trafficked to other lymphoid tissues in distant organs to exert a systematic immunoregulatory effect that influences the pathogenesis of various immune-related diseases, such as asthma and inflammatory bowel disease.

Citation138,Citation139,Citation140,Citation141 The immunoregulatory effect induced by

H. pylori strengthens the host’s resilience against microbiome perturbations and may result in increased colonic microbiota diversity. Additionally, chronic

H. pylori infection alters the acidic environment in the stomach, permitting more microorganisms to pass through the gastric acid barrier and colonize the distal gut. The gut microbiota may also induce Tregs and in turn, regulate

H. pylori–associated immune responses, which includes complex crosstalk between

H. pylori and colonic microbiota.