Figures & data

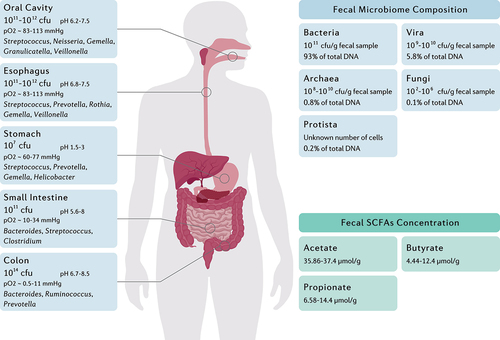

Figure 1. The main genera and total abundance of bacteria vary along the gastrointestinal tract. The colon is characterized by low levels of oxygen as well as the presence of enormous numbers and species of bacteria. On the other hand, the microbial composition and metabolite concentration of stool samples are distinguished from gut biopsies, in which the bacteria and the fungi constitute the majority and minority of total fecal DNA, respectively.Citation12–15 Fecal concentration of SCFAs are also demonstrated as they might be considered key regulators of the intestinal homeostasis.

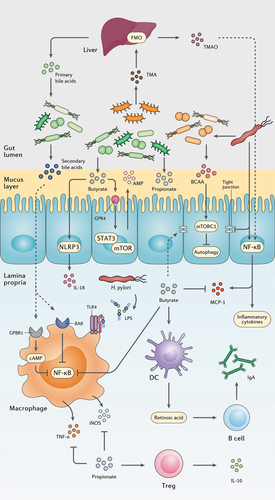

Figure 2. The interplay between the gut metabolome, H. pylori, and the host immune system. H. pylori induces chronic gastric inflammation through the activation of transcriptional factors such as NF-κB. By stimulating the production of BCAA from the gut microbiota, H. pylori activates the mTORC1 complex and ultimately inhibits autophagic response. H. pylori further disrupts the integrity of the gastric epithelial barrier by suppressing the expression of tight junction proteins. On the other hand, microbiota production of SCFAs and secondary bile acids modulate gastric inflammation and immune system activation by reducing NF-κB activation, promoting the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines, AMPs, and IgA, and preserving the integrity of the gut barrier.

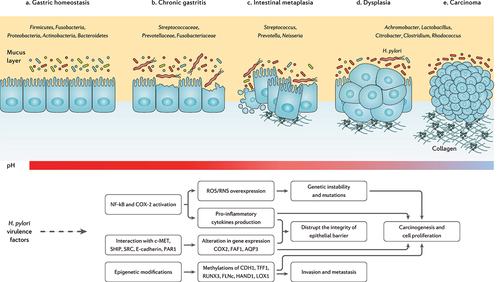

Figure 3. The progression of chronic gastritis toward gastric carcinoma has been characterized by the reduction in the Helicobacter genus, overgrowth of opportunistic bacteria, increased apoptosis, necrosis, and collagen production, changes in the cytoskeleton and polarity of the gastric epithelium, and gradual suppression of gastric acidity. The main mechanisms of action through which H. pylori virulence factors promote the risk of developing gastric cancer are further depicted.Citation71–73

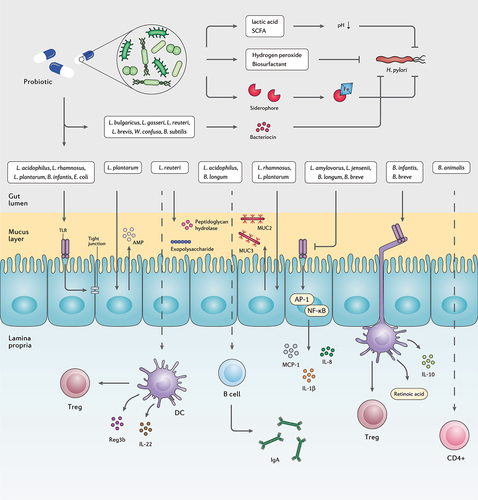

Figure 4. The interplay between probiotic strains, H. pylori, and the host immune system. Several probiotic strains can directly eliminate H. pylori cells by producing bacteriocins, siderophore, hydrogen peroxide, biosurfactant, lactic acid, and SCFAs. Probiotic bacteria can retain the activity of the gut barrier by stimulating the production of mucin and tight junction proteins. Certain probiotic species preserve the inherent structure of the gut microbiota by increasing the concentration of AMPs, peptidoglycan hydrolase, and exopolysaccharides. Furthermore, several probiotic bacteria regulate the host inflammatory response and prevent the development of chronic inflammation.

Table 1. Summary of studies examining the effects of probiotic co-supplementation to H. pylori eradication on the human gut microbiota.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this work.