Figures & data

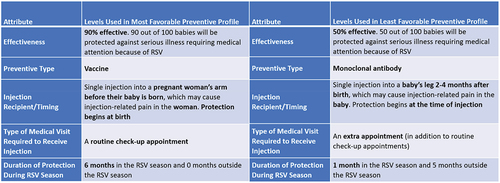

Table 1. Discrete choice experiment attributes and levels.

Table 2. Respondent characteristics by latent class.

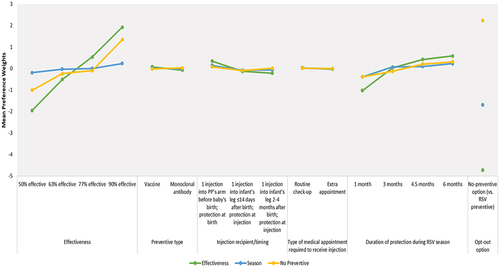

Figure 1. Attribute-level preference weights by latent class.

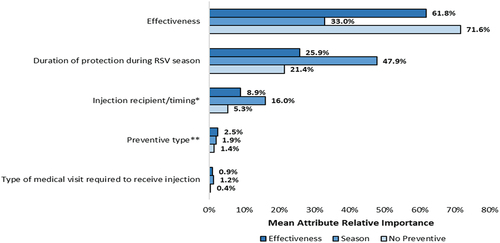

Figure 2. Attribute relative importance by latent class.

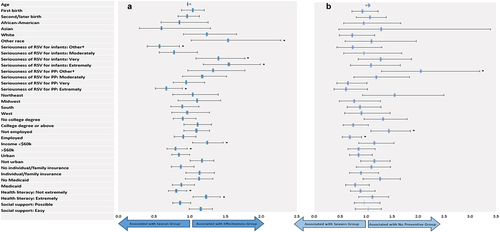

Figure 3. Association of respondent characteristics and latent class membership for (a) effectiveness group versus the season group and (b) no preventive group versus the season group.

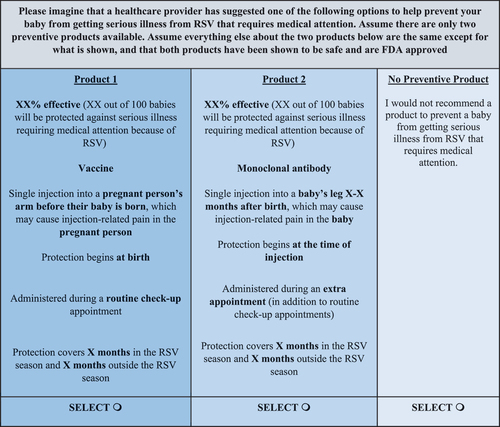

Figure A1. Example discrete choice experiment choice task.

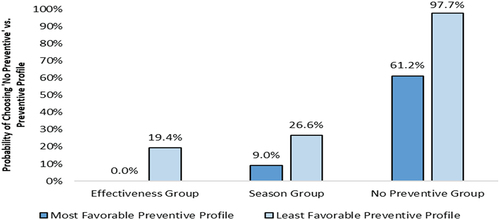

Figure A3. Probability of choosing the no-preventive option versus the most and least favorable RSV preventive profiles by latent class.