Figures & data

Figure 1. A foil design from one of the Vendel ceremonial helmets (500–700 AD). This foil depicts two figures wearing horned-helmets (terminating in bird beaks) and light robes. They are wielding swords upright in one hand and crossing spears in the other. Their feet are presented as if in motion, with one foot off the ground and the other set firmly forward, as if they had just leapt forth. As a result, they are interpreted as dancing, a classic example of the weapon dancer motif. (Viking Rune Citation2018)

Figure 2. Plate D of the Torslunda Die Matrix (500–700 AD). This foil depicts a horned, naked male figure—suggested to be Odin—dancing while wearing a sheathed sword and wielding two spears, one angled upward and another angled downward. Much like Figure , the figure’s feet is presented as if he had just leapt forward, interpreted as dance. This example, however, portrays the dancer with a spear-bearing warrior wearing a wolf-skin. This may suggest that this picture portrays the Norse god Odin leading a mortal warrior of the wolf-warrior group in the weapon dance. As a result it portrays the function of animistic transformation attributed to Odin and the weapon dancer ritual, in which the participated wolf-warrior would be granted the ability to transform into a wolf, lending him its predatory strength and speed. (Stjerna 1903)

Figure 3. Drawings from the different sections of one of the Danish Gallehus Horns (AD 400–500). Looking at the top-most section, one can see two naked horned-figures wielding various weapons in their hands (one holding what seems to be a spear and an axe, while the other holds a spear and a sword). To the left of these figures are what seem to be bare-chested figures holding swords and shields. As the Gallehus horns have been interpreted to provides scenes from Norse myth, it could be possible that this represents an early portrayal of the weapon dance. Where naked Odin-like figures are leading human warriors in the ritual, much like Figure . (Rasmussen 2011)

Figure 4. The Danish Års bracteate (400–500 AD). Representing a profile view of a helmeted Odin participating in the weapon dance ritual, the reader can observe a line of ornamented dots extending from his lower body on the left. This ornamentation can be interpreted as a tail, possibly that of a wolf. As such, this bracteate once again portrays the animistic functions attributed to the Norse weapon dance. (Weng 2001)

Figure 5. The Swedish Kungsängen figurine (800–1050 AD). This figurine portrays the Norse god Odin wearing a helmet with attached horns, terminating in bird beaks. These features have been interpreted as eagle beaks, alluding to the importance of the animal as a form often selected by Odin for shapeshifting. (Denstoredansk Citation2018)

Figure 6. A recreation of one of the Vendel ceremonial helmets (500–700 AD). Notice how a foil from Plate D of the Torslunda die, depicting Odin a wolf-warrior participating in the weapon dance, is featured prominently for all to see (top right design). When worn in a fire-lit hall, this design would be emphasized by the light, connecting the owner to this ritualistic tradition. (Deligiannis 2012)

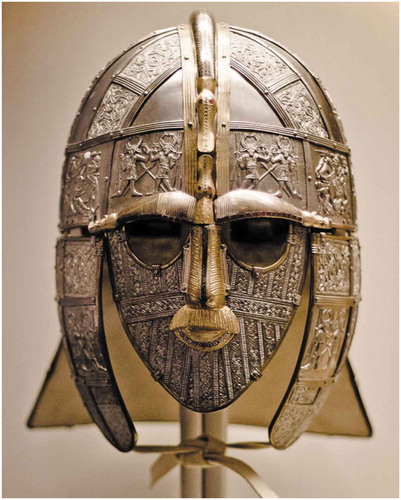

Figure 7. A recreation of the Sutton Hoo ceremonial helmet (500–700 AD). Notice how, like the above Vendel helmet, the dual weapon dancing Odin foil is featured prominently on the front of the helmet, meant to be seen by the viewer. This once again reinforces the idea that Iron Age elite wanted to emphasize this relief, and possibly the social values connected with it, in a ceremonial setting (Ramsay 2017)

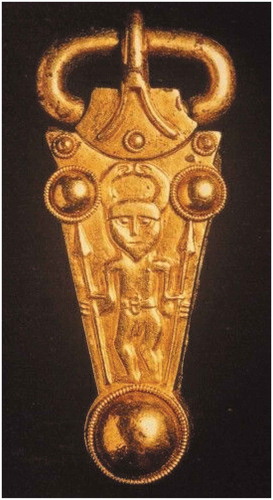

Figure 8. The Anglo-Saxon Finglesham belt (500–700 AD). Borrowing heavily from Scandinavian designs, this belt-buckle depicts a naked Wodan/Odin wearing a horned-helmet, wielding spears in either hand. Another example of the weapon dance on material culture, this piece is suggested to have belonged to a retainer of an Anglo-Saxon lord. This represents another instance where the elite were both connecting themselves and their retinue to images of warrior rituals. Much like the Vendel helmets, this may represent an elite-driven effort to signal both the social importance of a warrior identity and elite leadership of this identity (Viking Archeurope Citation2018)

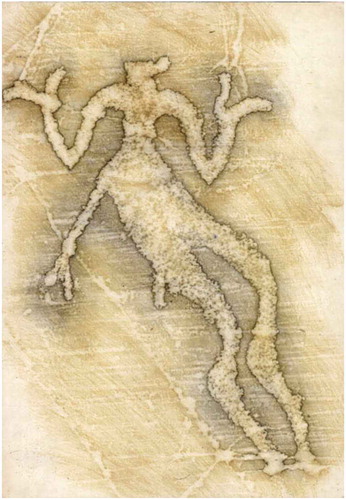

Figure 9. A rubbing of the Järrestad “Dancing God”. Starting with the head, one can see possible bird-like characteristics of the figure—representing the head of a swan or goose. Proceeding downward, the un-pecked band splitting the figure’s two upper halves seems to be attached to the scabbard and the potential knife sheath shown in the image, possibly representing a belt. Pairing the large size this figure with its stance, shown with its knees bent and its legs together (as if about to leap), it is hard to deny the ritualistic interpretations attributed to this image. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives Citation2008)

Figure 10. The “Dancing God” of Järrestad and the various motifs surrounding it. As one can see, a large amount of footprint images and cupmarks surround the more central figure on all sides. If the current interpretations of these signs are accurate, specifically their various associations to divine and ritual contexts, it further reinforces the potential socio-ritual significance of the central dancing figure. (Coles, Citation1999)

Figure 11. A drawing of the various horned and non-horned weapon-bearing figures observed at Bro Utmark. As one can see, the horned figures are placed centrally in the motif with a particular emphasis on their weapons and how they are wielding them. As stated in the paper, John Coles suggests that their bearing seems to give off an impression of waving. (Coles, Citation2004)

Figure 12. John Coles’ drawing of the layout of the Bro Utmark petroglyphs. As shown by the drawing, the weapon-bearing figures were placed centrally in not only their own panel, but also more or less centrally in the midst of all the images found at Bro Utmark—perhaps indicating their importance to the groups who maintained them. (Coles, Citation2004)

Figure 13. A close-up image of the horned figures of the Bro Utmark panel. Comparing the central figure on the left to the Järrestad figure, one can observe a similar leg position which gives off the impression of built-up tension—as if the figure were about to leap. This suggests that not all of the figures depicted were stationary. Overall, paired with the acrobat placed above them and the particular emphasis which all show in waving their weapons, a general impression of motion is given off. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2015)

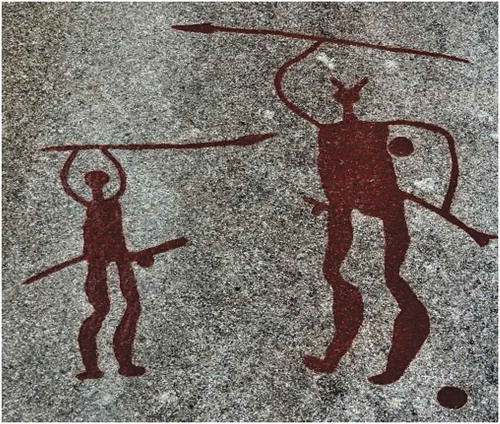

Figure 14. A rock carving from Tanum in Bohüslan depicting a similar motif to that found at Bro Utmark. In this carving, a large horned-figure and a smaller non-horned figure are wielding spears in a position similar to that of Bro Utmark, possibly waving them. Both of the figures are also depicted naked and with sword scabbards attached to their waists. Several characteristics—including the cup marks surrounding the figure on the right, its exaggerated characteristics and larger size, and its horns—have led many to characterize this motif as a possible depiction of a heroic or divine figure from Bronze Age myth leading a mortal in the weapon dance (Horn et al. Citation2018).

Figure 15. The panel found at Hede, Kville, on which this case study focuses. As shown, a large number of both horned and non-horned figures are depicted amongst several different forms of abstract imagery. The large amount of figures shown with weaponry, and what seems to be many shields and swords deposited throughout the scene, gives off an impression of battle (expanded on below) (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2019)

Figure 16. The possible motif of ritual dancing taken from the uppermost limit of the Hede panel. As stated, this scene depicts two horned figures possibly dancing with their weapons as a non-horned figure observes the ritual taking place. Looking at the two right-most figures, it seems that tail-like lines are descending from their lower bodies. These figurative details could represent an instance of animistic transformation, with both the horned dancer and non-horned adorant shapeshifting as a result of the possible ritual which is taking place. This possibility is reinforced by the cup mark placed above the two dancers. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2019)

Figure 17. A motif found close to the battle scene at the Hede panel. Much like the scene placed above the battle motif, this scene could represent yet another instance of a possible weapon dancing ritual. While sedentary leg-wise, the figure on the left is waving its weapon and the figure on the right has its arms raised in possible adoration of the weapon-waving figure. These figures seem to be placed amongst various cupmarks and possibly discarded shields, suggesting a possible connection with power and battle. The repetition of this motif of ritualistic motion is interesting, especially when taking in its possible martial surroundings. (Swedish Rock Art Research Archives 2019)