Figures & data

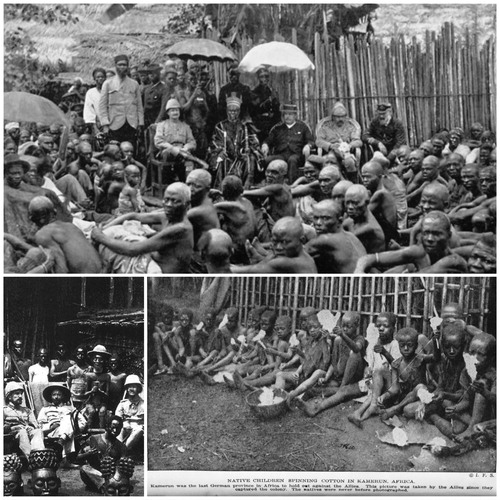

Figure 2 A corporate feedback loop establishes a baseline rhetoric of local suffering. Screenshots from an oil promotional video, The Chad/Cameroon Development Project: Views and Voices (Citation1999). Source: The Chad/Cameroon Development Project: Views and Voices (Citation1999). Collage by author.

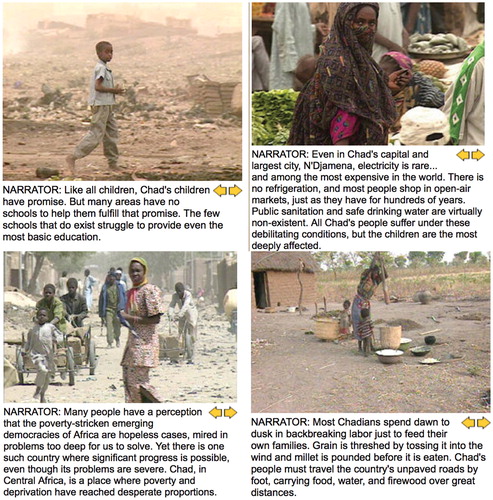

Figure 3 A collage of colonial imagined geographies of “local” African landscapes. From the top right is an opening scene of the oil consortium promotional video, Chad, Land of Promise (Citation2003), capturing the sun setting on an oil rig. This image has been juxtaposed with countless other iterations, each reflective of the pervasive colonial fantasy of the “promise” of “empty” frontier spaces in Africa. Collage by author.

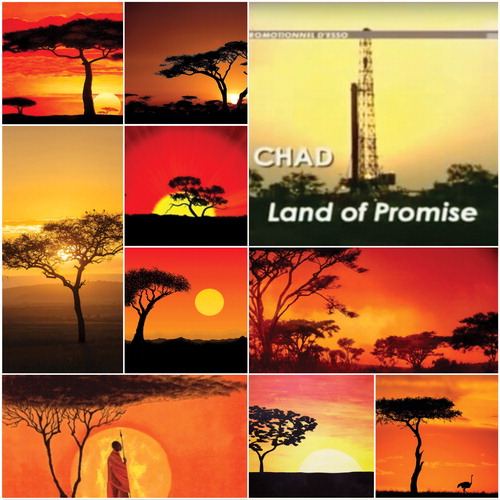

Figure 4 Online archives of the World Bank Group’s public briefings and press announcements regarding the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline (1999–2005). These selected sites illustrate the frequency of references to and naturalizations of poverty in the early phases of the project. Source: World Bank Group. Collage by author.

Figure 5 The former director of Esso Chad, Ronald William Royal, tours Esso facilities and neighboring towns in southern Chad. Source: Tchad: Main basse sur l’or noir (Citation2005). Collage by author.

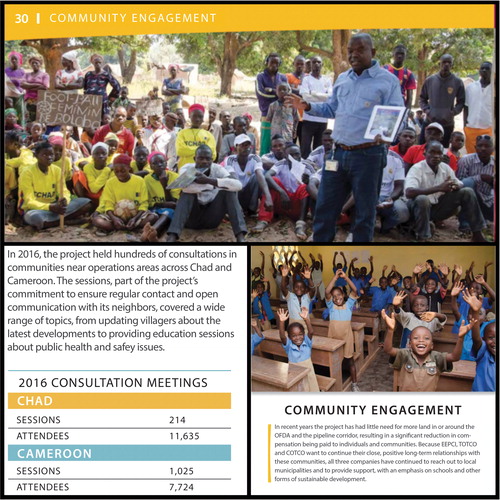

Figure 6 Images of a passive and supportive local appear throughout the pages of Esso’s Year-End Reports for the Chad/Cameroon Development Project. Source: Esso Chad/Cameroon (Citation2016). Collage by author.

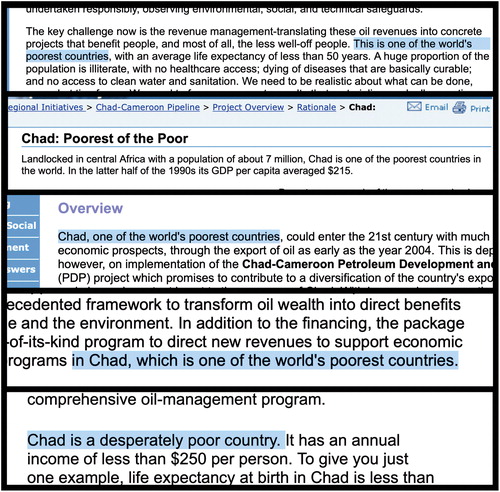

Figure 7 Juxtaposing oil consortium images with images from colonial archives reveals similarities in visual aesthetics and the colonial fantasy of a passive local. Top: A ceremony marking the formal “incorporation” of the Ewi of Ados Kingdom into the British Lagos Protectorate, 1897. Source: The Queens Empire: A pictorial and descriptive record. London: Cassell and Company, 1897–99 (FCO Historical Collection DA11 QUE). Bottom right: Photograph of children spinning cotton in Kamerun (Cameroon) in 1919. The original caption reads, “Native Children Spinning Cotton in Kamerun, Africa. Kamerun was the last German province in Africa to hold out against the Allies. This picture was taken by the Allies since they captured the colony. The natives were never before photographed.” Source: Kelly Miller’s History of the World War for Human Rights, originally published in 1919 by A. Jenkins and O. Keller. Bottom left: Young boys surround seated German colonists in Bamoun, Kamerun/Cameroon, 1905. Collage by author.