Figures & data

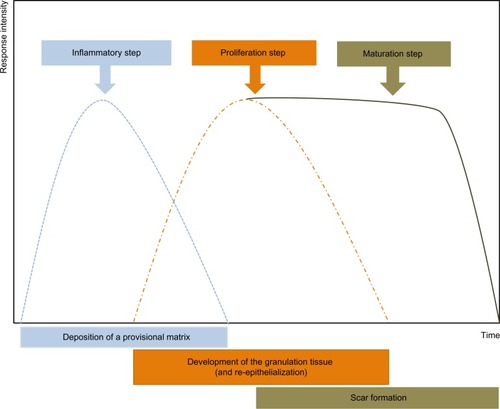

Figure 1 The various phases of the healing process.

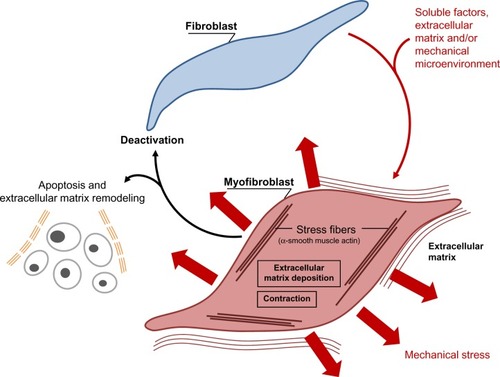

Figure 2 Schematic illustration showing the evolution of the (myo)fibroblast phenotype.

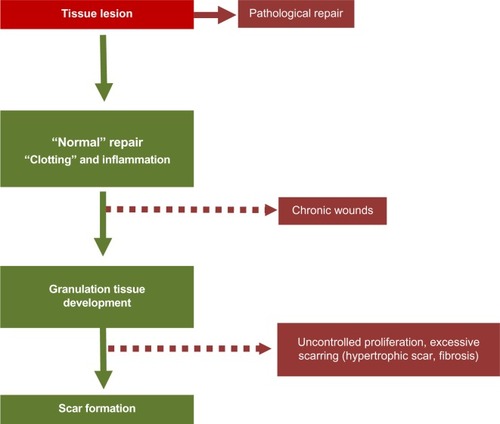

Figure 3 Pathological situations.

Figure 4 Processes leading to normal wound repair and pathological scarring.

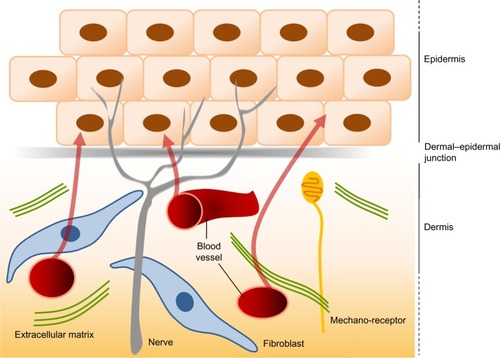

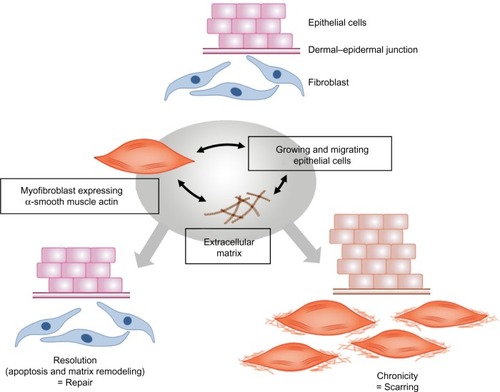

Figure 5 The interactions between the dermis and the epidermis.