Figures & data

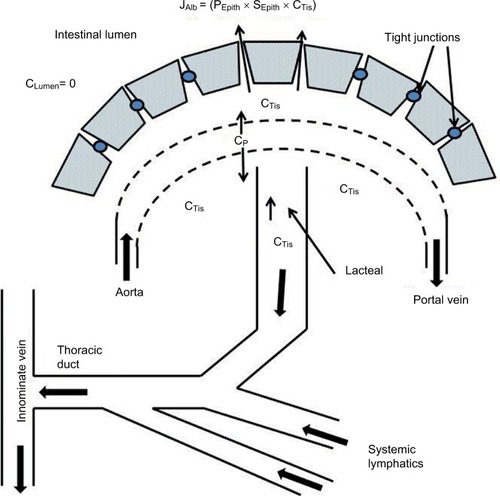

Figure 1 Schematic diagram of normal intestinal mucosa.

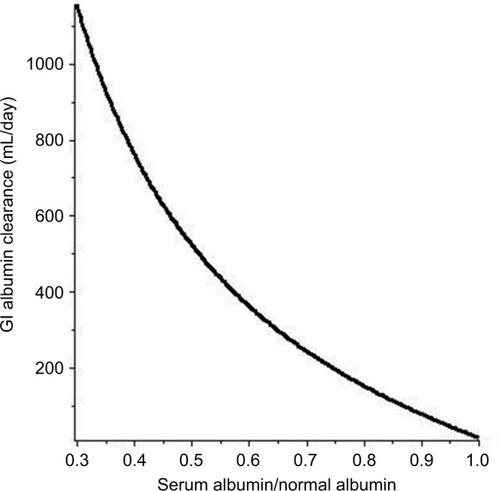

Figure 2 The predicted relationship between the increase in GI albumin clearance and the resulting steady-state serum albumin (serum albumin/normal albumin) in a PLE subject with normal renal and hepatic functions.

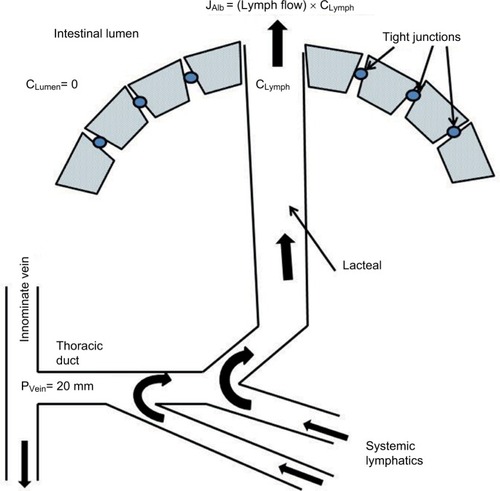

Figure 3 Schematic diagram illustrating the pathophysiology for the PLE produced by increased lymphatic pressure resulting from increased venous pressure (PVein).

Abbreviation: PLE, protein losing enteropathy.

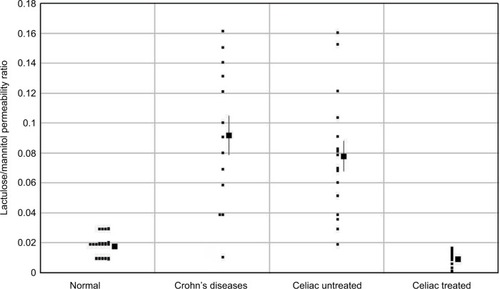

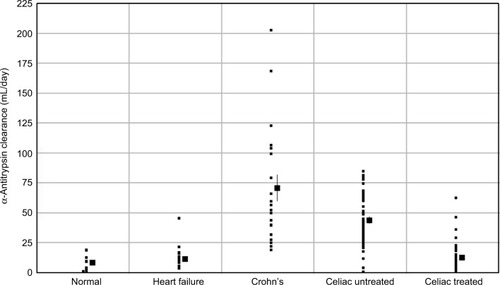

Figure 4 Fecal α-antitrypsin clearance in various disease states.

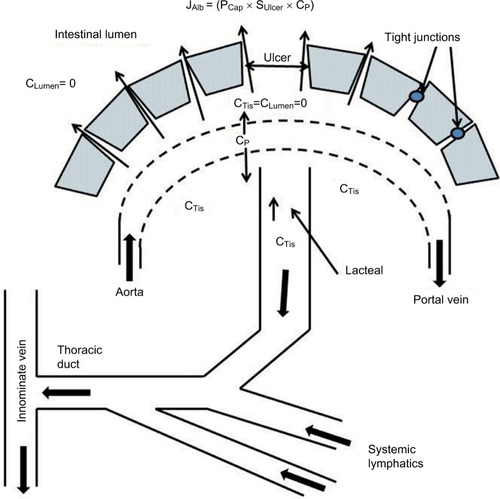

Figure 5 Schematic diagram of the PLE occurring in diseases with mucosal erosions.

Abbreviation: PLE, protein losing enteropathy.

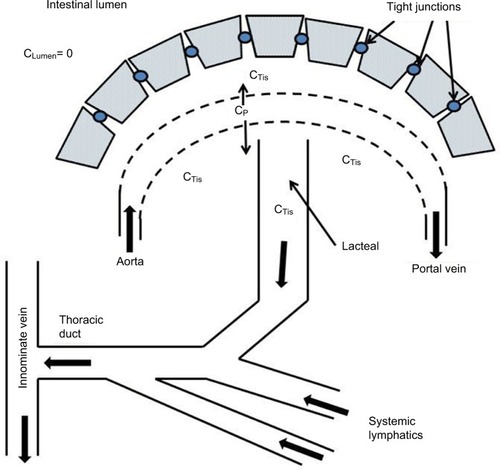

Figure 7 Schematic diagram of the PLE occurring in diseases without mucosal erosions.

Abbreviation: PLE, protein losing enteropathy.