Figures & data

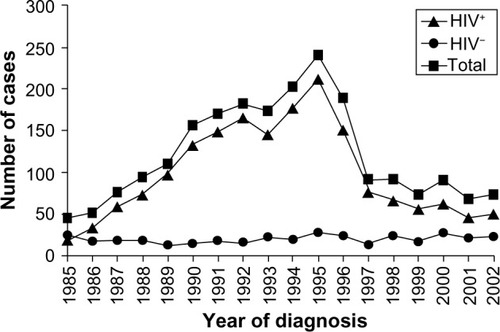

Figure 1 Evolution of the incidence of cryptococcosis, by year of diagnosis in France (1985–2001), as reported to the National Reference Centre for Mycosis.

Abbreviation: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

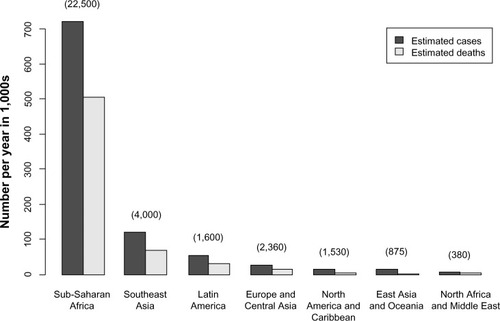

Figure 2 Global incidence and mortality from cryptococcal meningitis among United Nations global regions from 1997 to 2007.

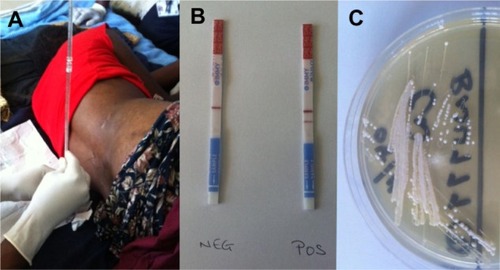

Figure 3 (A–C) Diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. (A) Lumbar puncture being performed on a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient with suspected meningitis in Malawi. (B) Lateral flow immunoassay test strips for cryptococcal antigen detection (the strip on the left shows a negative result, indicated by a single horizontal “control” band in the center; the strip on the right shows a positive result, indicated by adjacent horizontal “control” and “test” bands). (C) Cryptococcus neoformans growing on Sabouraud media. Images kindly supplied by Kate Gaskell, College of Medicine, University of Malawi, and Brigitte Denis, Malawi Liverpool wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme.

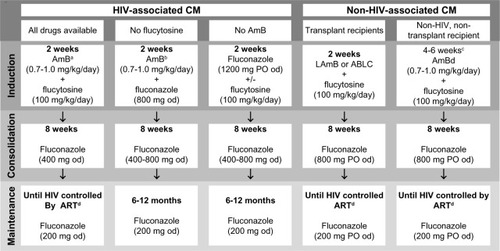

Figure 4 Treatment options for cryptococcal meningitis (CM), summarized from infectious Diseases Society of America and world Health Organization guidelines.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; AmB, amphotericin B; LAmB, liposomal amphotericin B (3–6 mg/kg/day); ABLC, amphotericin B lipid complex (5 mg/kg/day); od, once daily; PO, per os (by mouth); ART, antiretroviral therapy.

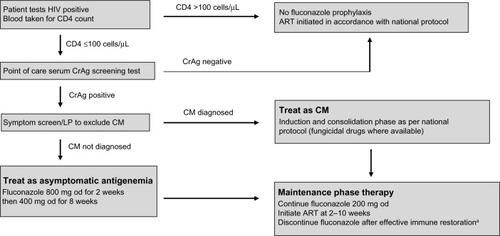

Figure 5 A screening and management strategy for asymptomatic antigenemia.

Abbreviations: HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CrAg, cryptococcal antigen; LP, lumbar puncture; CM, cryptococcal meningitis; od, once daily; ART, antiretroviral therapy.

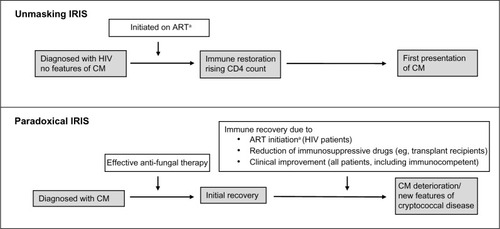

Figure 6 Types of immune restoration inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) in cryptococcal disease.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; CM, cryptococcal meningitis.

Table 1 Prospective open-label randomized trials to assess optimal timing of antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation in human immunodefciency virus (HIV)-infected patients with cryptococcal meningitis (CM)