Figures & data

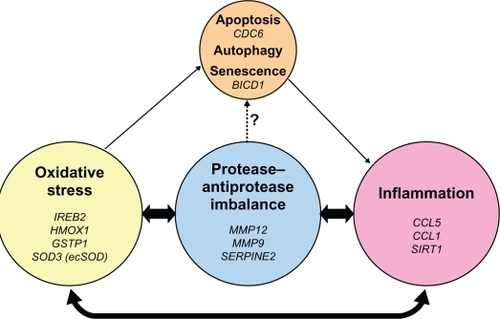

Figure 1 Histologic features of chronic bronchitis. (A) A section of bronchiole wall with luminal accumulation of mucous, goblet cell hyperplasia, basement membrane thickening (arrow), and scattered mononuclear inflammatory cells. (B) A bronchial wall with squamous metaplasia of the luminal epithelium (arrow head) and hyperplasia of the subepithelial seromucinous glands (arrow).

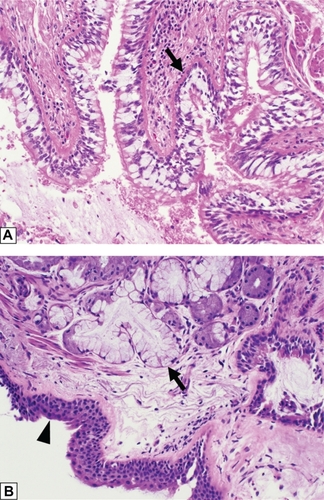

Figure 2 Histologic features of centrilobular emphysema. A section of lung tissue shows fragmented and “free-floating” alveolar septa (arrow) characteristic of emphysema.

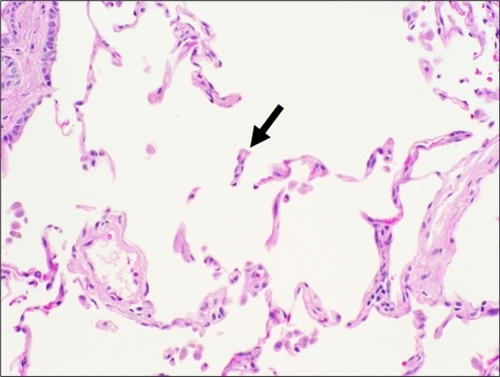

Figure 3 Histologic features of small airways disease. A section of lung tissue shows accumulation of macrophages with smoker’s pigment (arrow) within and around a respiratory bronchiole (arrow head).

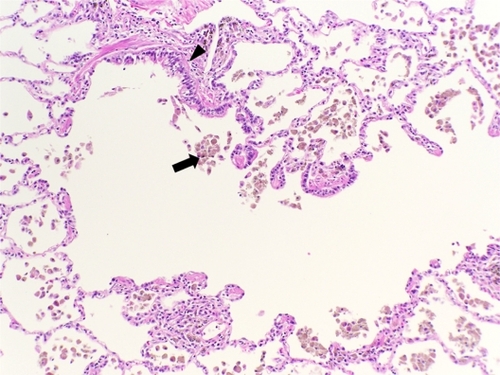

Figure 4 Pathogenic triad of COPD: oxidative stress, protease–antiprotease imbalance, and inflammation. Oxidative stress, protease–antiprotease imbalance and inflammation each are important in the pathogenesis of COPD; however, they constantly interact and may at times overlap with each other in the overall pathogenesis of COPD. As a consequence of oxidative stress, in particular cigarette smoking-induced oxidative stress, apoptosis, autophagy, and senescence are each potential lung cell fates. Senescent cells express a pro-inflammatory phenotype. Proteases, such as neutrophil elastase, have been shown in vitro to induce airway epithelial apoptosis,Citation83 but this relationship has not yet been specifically demonstrated in human subjects. Listed in italics are the genetic polymorphisms that have been reported and discussed in this review, to be associated with COPD or emphysema in that area of the pathogenic triad.