Figures & data

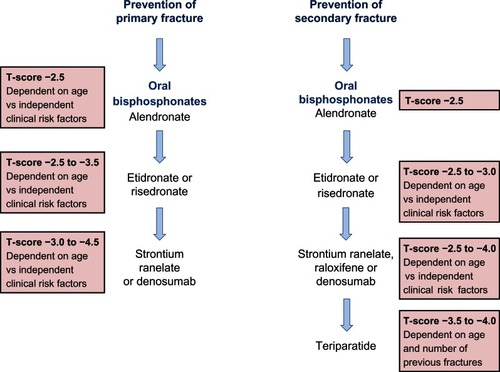

Figure 1 The cells responsible for bone remodeling, highlighting key signaling pathways that are targets for therapies recommended for the prevention of osteoporotic fracture.

Abbreviations: CatK, cathepsin K; CTR, calcitonin receptor; E2, estrogen; ERα, estrogen receptor; LRP5/6, lipoprotein-related protein 5/6; OPG, osteoprotegerin; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR, PTH receptor; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB; RANKL, RANK ligand.

Figure 2 Key milestones in the lifecourse of osteoporosis therapy. Strontium ranelate is not approved by the FDA but all other agents have been approved both by the FDA and EMA.

Abbreviations: EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IV, intravenous.

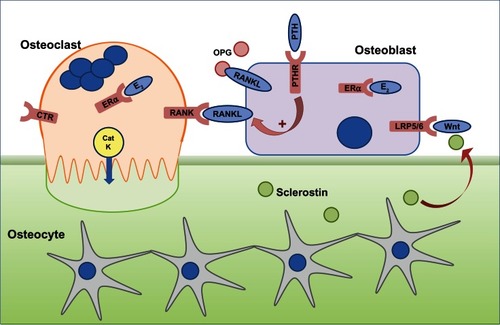

Figure 3 Sites of action of different classes of drugs that are either in clinical use (left hand side) or in development (right hand side).

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; BP, bisphosphonate; CaSR, calcium-sensing receptor; CatK, cathepsin K; CTR, calcitonin receptor; ERα, estrogen receptor; LRP5/6, lipoprotein-related protein 5/6; OPG, osteoprotegerin; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR, PTH receptor; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB; RANKL, RANK ligand; OB, osteoblast; OC, osteoblast.

Table 1 Serum biomarkers for osteoporosis

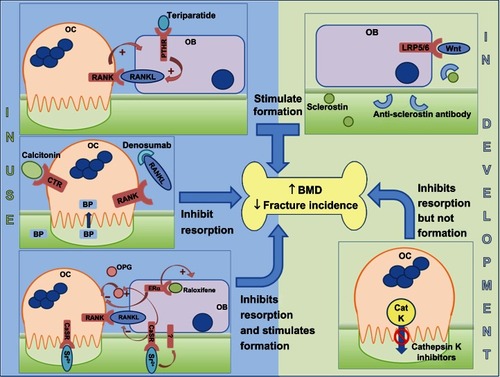

Figure 4 A summary of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (available at http://publications.nice.org.uk) for the therapeutic management of primary and secondary osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women.