Figures & data

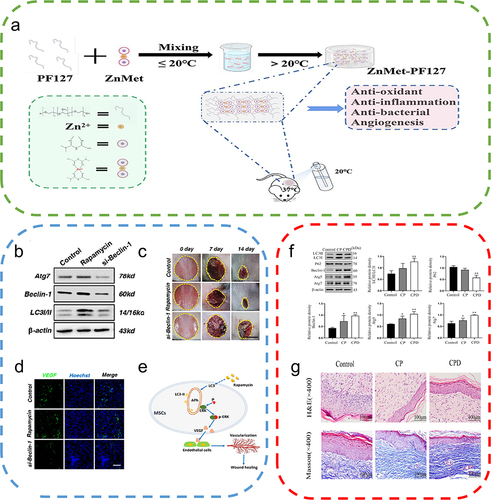

Figure 1 The mechanisms underlying skin wound repair by autophagy-based nanomaterials. Autophagy is strongly related to skin repair and exerts anti-infective anti-inflammatory and antioxidation effects, thereby promoting cell proliferation and differentiation and neovascular formation.

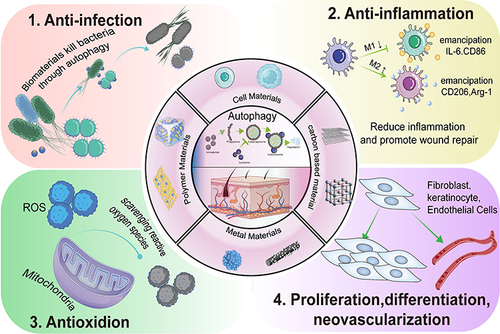

Figure 2 Regulation of autophagy. (a) The ULK1 complex undergoes dephosphorylation in response to external nutrient deprivation or external cell injury to induce autophagy. (b) The PI3KC3 complex, ATG 9, and ATG 18 mediate the formation of autophagosome membranes and the recruitment of ATG. (c) ATG 12 UBL system. (d) The LC3-PE UBL system is involved in autophagosome maturation and transport. Autophagy is strongly related to several factors, among which mTOR plays a key role. AMPK and ERK 1/2 upregulate autophagy by inhibiting mTOR phosphorylation, while the P53 and PI3K/AKT pathways lead to the inhibition of autophagy.

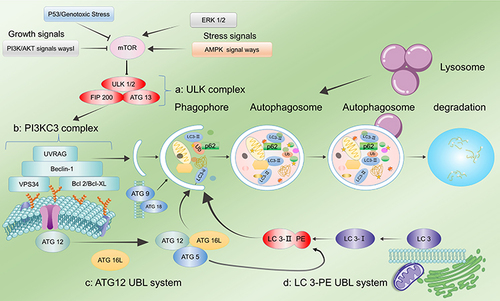

Figure 3 The role of autophagy in skin wound healing. Autophagy is involved in four phases of wound healing (hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodelling). Autophagy facilitates the survival, proliferation and migration of neutrophils, macrophages, endothelial cells, keratinocytes and fibroblasts, thereby improving their biological function and enhancing wound healing. (Image created with BioRender.com).

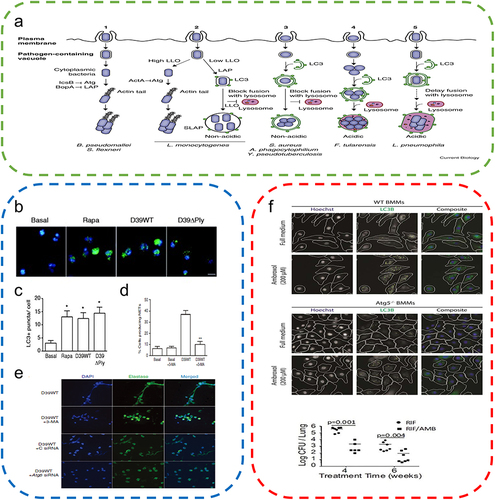

Figure 4 Autophagy in bacterial infection. (a) Removal of bacteria from the host cell by autophagy. After rapamycin or IFNγ treatment, bacteria such as M. tuberculosis and S. Typhimurium were digested by phagocytosis. Reproduced from Cemma M, Brumell JH. Interactions of pathogenic bacteria with autophagy systems. Curr Biol. 2012;22(13):R540–R545.Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc.Citation62 (b) After rapamycin treatment and Streptococcus pneumoniae infection, LC3 levels in neutrophils significantly increased, promoting autophagy. (c) Quantitative analysis of the LC3 levels in neutrophils. (t-tests) (d) Quantitative analysis of NET expression in neutrophils. (t-tests) (e) Expression of NETs was significantly reduced after inhibition of autophagy in neutrophils using the autophagy inhibitors 3-MA, Atg5, and siRNA, indicating that autophagy is essential for NET formation in neutrophils in humans infected with pneumococci. Reproduced from Ullah I, Ritchie ND, Evans TJ. The interrelationship between phagocytosis, autophagy and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps following infection of human neutrophils by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Innate Immun. 2017;23(5). © The Author(s) 2017. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).Citation55 (f) Significant increase in the expression levels of LC3 in macrophages of wild-type and autophagy-deficient mice after reduced Mycobacterium tuberculosis following ambroxol treatment. Reproduced from Choi SW, Gu Y, Peters RS, et al. Ambroxol induces autophagy and potentiates rifampin antimycobacterial activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(9):e01019–18. Copyright © 2018, American Society for Microbiology. Citation61*P<0.05, **P<0.01, relative to the Basal group.

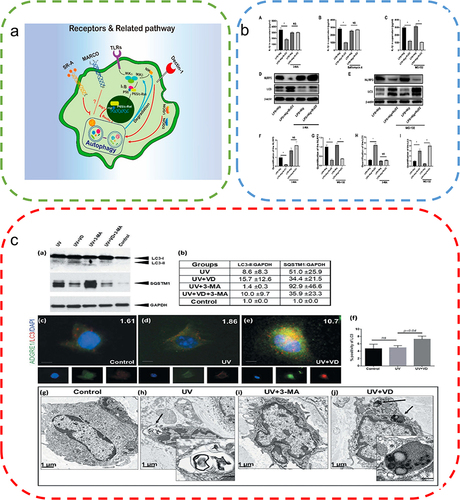

Figure 5 Autophagy attenuates the inflammatory response. (a) Regulation of macrophage functions by the autophagic pathway. Reproduced from Wu MY, Lu JH. Autophagy and macrophage functions: inflammatory response and phagocytosis. Cells. 2019;9(1):E70. Copyright © 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).Citation76 (b) RvD2 promotes NLRP3 degradation through autophagy. (One-way ANOVA) Reproduced from Cao L, Wang Y, Wang Y, Lv F, Liu L, Li Z. Resolvin D2 suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome by promoting autophagy in macrophages. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(5):1222. © Cao et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution.Citation70 (c) Vitamin D augments autophagic flux in macrophages of UV exposed mouse skin. Reproduced from Das LM, Binko AM, Traylor ZP, Peng H, Lu KQ. Vitamin D improves sunburns by increasing autophagy in M2 macrophages. Autophagy. 2019;15(5):813–826. Copyright © 2019, The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License.Citation7 *P<0.05.

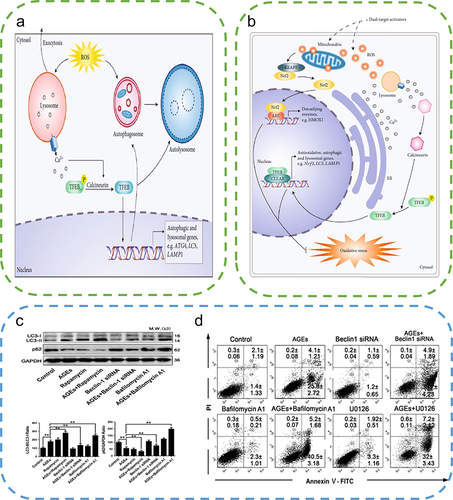

Figure 6 Autophagy alleviates ROS accumulation around the wound. (a) High levels of ROS stimulate TFEB dephosphorylation and activate autophagy, thereby removing excess ROS. (b) Sulforaphane induces low levels of ROS to activate the Nrf2 pathway and promotes TFEB-dependent autophagy to eliminate ROS. Reproduced from Li D, Ding Z, Du K, Ye X, Cheng S. Reactive oxygen species as a link between antioxidant pathways and autophagy. Oxid Med Cell Longev.2021;2021:5583215. Copyright © 2021 Dan Li et al. Creative Commons Attribution License.83 (c) Examination of the changes in LC3 and P62 protein expression by Western blotting to evaluate the effects of AGEs indicated the promotion of autophagy by AGEs. (One-way ANOVA) (d) Apoptosis was detected by the annexin V-FITC/PI kit, which indicated that autophagy inhibition exacerbated AGEs/ROS -induced apoptosis. Reproduced from Xu L, Fan Q, Wang X, Zhao X, Wang L. Inhibition of autophagy increased AGE/ROS-mediated apoptosis in mesangial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(11):e2445. Published by Nature Publishing Group under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Citation87 **P<0.01.

Table 1 Regulation of Biomaterial-Based Autophagy in Skin Repair

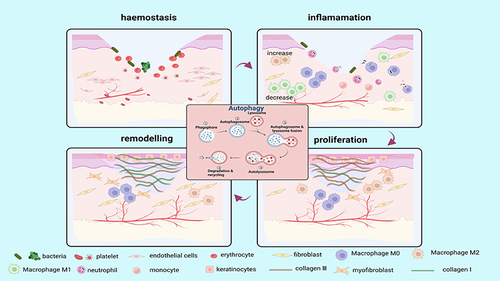

Figure 7 Autophagy-based biomaterials promote wound repair. (a) Schematic diagram of the preparation process and application of ZnMet-Pluronic F127. Reproduced from Liu Z, Tang W, Liu J, et al. A novel sprayable thermosensitive hydrogel coupled with zinc modified metformin promotes the healing of skin wound. Bioact Mater. 2023;20:610–626. © 2022 The Authors. CC BY-NC-ND license. Citation122 (b) Changes in ATG7, Beclin-1, and LC3 protein levels after treatment of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) with the autophagy activator rapamycin and the autophagy inhibitor si-Beclin-1. (c) Cutaneous wound healing in different groups of mice, with rapamycin-treated MSCs exhibiting the highest therapeutic effect on wound healing. (d) Immunofluorescence staining of VEGF in wound area tissue after 2 weeks, where rapamycin-treated MSCs promoted the expression of VEGF on the wound surface. (e) Autophagy regulates ERK phosphorylation to increase VEGF release from MSCs, which in turn promotes endothelial cell vascularization. Reproduced from An Y, Liu WJ, Xue P, et al. Autophagy promotes MSC-mediated vascularization in cutaneous wound healing via regulation of VEGF secretion. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):58. Published by Nature Publishing Group under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.Citation129 (f) Effect of the nanocomposite membrane loaded with chitosan and polyvinylpyrrolidone (CP) and the nanocomposite membrane loaded with chitosan, polyvinylpyrrolidone and dihydroquercetin (CPD) on the expression of LC3II/I, P62, Beclin-1, ATG5, and ATG7, with CPD significantly promoting autophagy-related protein expression. (One-way ANOVA) (g) Images of H&E-stained and Masson-stained skin wounds treated with nanocomposite membrane CP and CPD on day 16. Reproduced from Zhang J, Chen K, Ding C, et al. Fabrication of chitosan/PVP/dihydroquercetin nanocomposite film for in vitro and in vivo evaluation of wound healing. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;206:591–604. Copyright © 2022, Elsevier Inc.Citation121 *P<0.05, **P<0.01, relative to the control group.