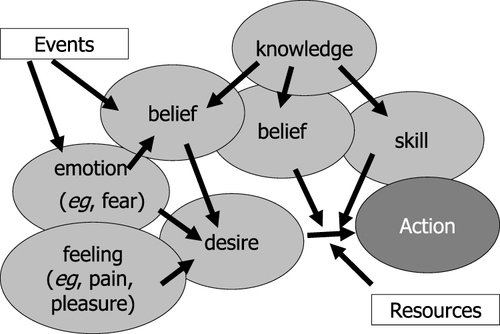

Notes: This model can be applied to all our actions,

eg, increasing the dose of insulin if blood glucose is high. The desire–belief pair represents the main pro-attitude causing this action, playing an instrumental role;

eg, the desire to avoid the recurrence of hyperglycemia and the belief that increasing the insulin dose will satisfy this desire. In addition, the patient must have knowledge (

eg, that insulin lowers blood glucose) and skills (knowing how to decide on the insulin dose). Emotions also influence desires, such as fear of weight gain, which may reduce the desire to avoid hyperglycemia. Furthermore, other beliefs may also alter this desire, such as the belief that increasing the insulin dose will result in the risk of hypoglycemia. Thus, beliefs, in addition to the instrumental role that makes them the driver of our actions, can perform another role associated with emotions. These two types of mental states are triggered by events (for example, the recent occurrence of hypoglycemia). In addition, in this figure, we have represented the possible effect of feelings (such as pain and pleasure) and the involvement of exogenous factors as resources necessary for the realization of the action. This “physiology of the mind” is described in detail in the cited reference. Reach G. The Mental Mechanisms of Patient Adherence to Long Term Therapies: Mind and Care, Foreword by Pascal Engel, Philosophy and Medicine Series, Springer, 2015. This figure was adapted from a figure published in The Mental Mechanisms of Patient Adherence to Long-Term Therapies, Mind and Care, by Gérard Reach Springer © 2015, with Springer’s permission for reprint.

Citation15