Figures & data

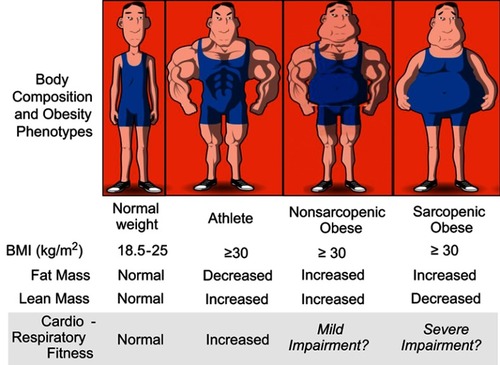

Figure 1 Obesity phenotypes, cardiac function and cardiorespiratory fitness. The figure highlights the proposed major role of lean mass in the development of cardiac dysfunction and cardiorespiratory fitness, suggesting that individuals with similar body mass index (BMI) can present a different body composition, resulting in different cardiac function and cardiorespiratory fitness. Reprinted from Mayo Clin Proc., 92(2), Carbone S, Lavie CJ, Arena R. Obesity and heart failure: focus on the obesity paradox, 266–279, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.Citation9

Figure 2 Obesity and risk for heart failure. Obesity increases the risk of heart failure (HF), particularly of HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (top panel) compared to HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (bottom panel). Reprinted from J Am Coll Cardiol, 69(9), Pandey A, LaMonte M, Klein L, et al, Relationship between physical activity, body mass index, and risk of heart failure, :1129–1142, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.Citation39

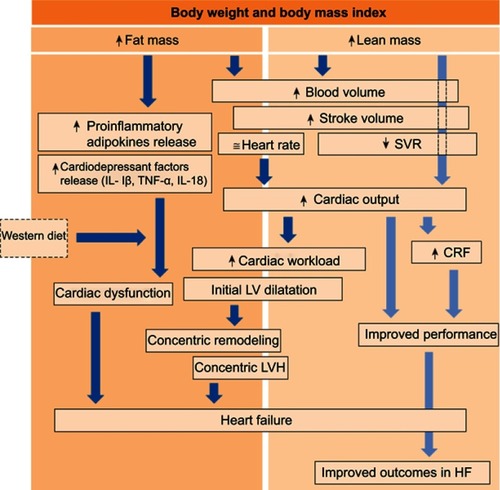

Figure 3 Body composition and heart failure. Proposed mechanisms driving obesity to heart failure (HF) and to the obesity paradox once HF is diagnosed. The dark blue arrows indicate the potential detrimental effects of body composition components (fat mass and lean mass) on cardiac function and eventually HF development. The light blue arrows indicate the potential mechanisms by which body composition improves cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF). Reprinted from Mayo Clin Proc., 92(2), Carbone S, Lavie CJ, Arena R. Obesity and heart failure: focus on the obesity paradox, 266–279, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.Citation9

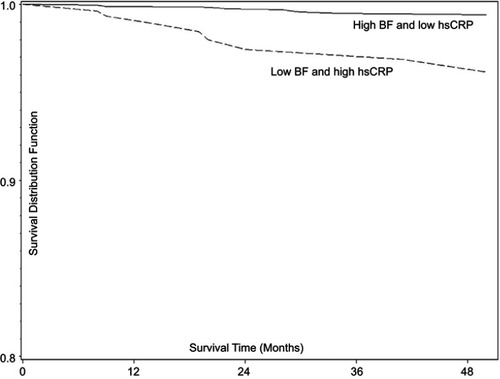

Figure 4 Body fat and systemic inflammation in coronary heart disease. Survival estimates (Kaplan–Meier) by body fat (BF) and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) strata: low hsCRP = CRP<3 mg/L; high hsCRP = CRP ≥3 mg/L; low BF = BF<25%; high BF ≥25%. Copyright ©2016. Reproduced from De Schutter A, Kachur S, Lavie CJ, Boddepalli RS, Patel DA, Milani RV. The impact of inflammation on the obesity paradox in coronary heart disease. Int J Obes (Lond). 2016;40(11):1730–1735.Citation85

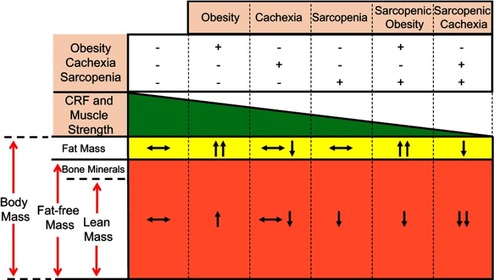

Figure 5 Relationship between body composition phenotypes, cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) and muscle strength in heart failure. Body composition compartments changes can directly affect CRF and muscle strength in patients with heart failure. Reproduced with permission from Ventura HO, Carbone S, Lavie CJ. Muscling up to improve heart failure prognosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20(11):1588–1590. © 2018 The Authors. European Journal of Heart Failure © 2018 European Society of Cardiology.Citation35