Figures & data

Table 1. Sociodemographic comparisons between full-term (n = 31) and preterm children (n = 30).

Table 2. Total of preterm births (n = 30) split by related risk factors followed by mood of delivery, according to medical records.

Table 3. Pre-natal and post-natal comparisons between full-term (n = 31) and preterm children (n = 30).

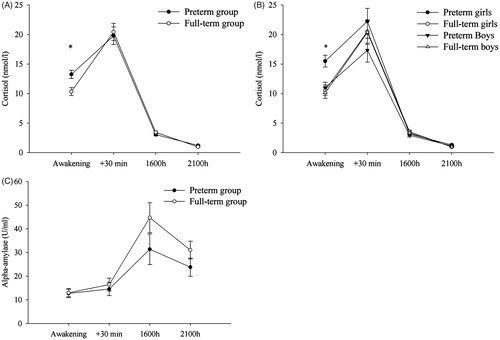

Figure 1. (A) Salivary cortisol profile of preterm and full-term children. (B) Salivary cortisol profile of preterm and full-term children split by sex. (C) Salivary alpha-amylase (sAA) profile of preterm and full-term children. Statistical analyses were performed using log-transformed data (log +1). The graphs show the estimated marginal means (raw scores adjusted for covariates) of cortisol concentrations as well as sAA concentrations measured on two consecutive days. Error bars represent standard error of mean (SEM). For cortisol, a significant preterm birth by time interaction and a trend of preterm birth by sex interaction were observed in the conducted analyses. Post-hoc analyses (Bonferroni adjusted for multiple comparisons) revealed that preterm children differed from their full-term peers at awakening cortisol concentrations, with preterm girls displaying significant larger cortisol at awakening than full-term girls. Additionally, preterm children showed an attenuated CAR (see “Results” section for additional information). No sex-differences were found in CAR. *p < 0.05 (post-hoc Bonferroni-adjusted univariate tests).

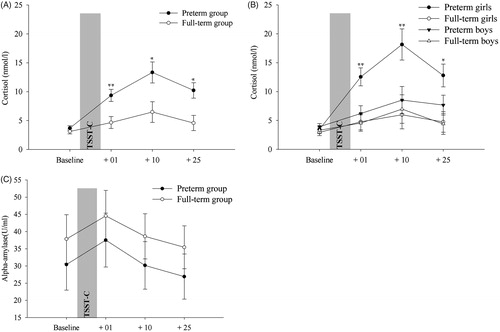

Figure 2. (A) Salivary cortisol in response to the Trier Social Stress Test for Children (TSST-C) for preterm and full-term children. (B) TSST-C results from preterm and full-term children split by sex. (C) sAA response to the TSST-C. Statistical analyses were performed using log-transformed data (log +1). The graphs show the estimated marginal means (adjusted raw data for covariates). Error bars represent standard error of mean (SEM). Stress-induced cortisol changes over time, and a significant main preterm birth effect was found using Bonferroni adjusted analyses. Furthermore, such effect was more pronounced in girls, with preterm girls showing significant larger cortisol response to TSST-C than full-term girls. (A) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 between preterm and full-term children and (B) *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (post-hoc Bonferroni-adjusted univariate tests) between preterm girls and full-term girls.

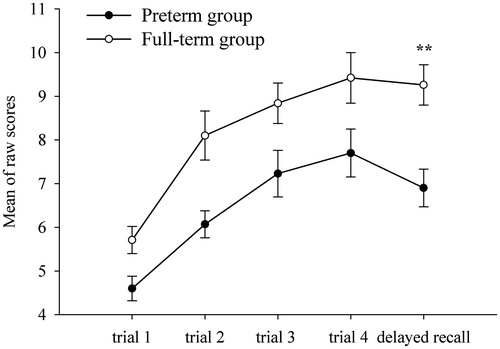

Table 4. WRAML2 performance and group comparisons.