Figures & data

Table 1 Lists of behavioral outcomes associated with deployment conditions and responses

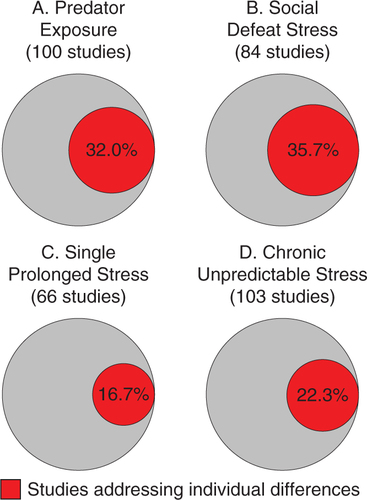

Fig. 1 Proportional diagrams of the number of studies from a PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) literature search (all references until December 2013) for: (A) (stress disorder or depressive disorder or anxiety disorder) AND animal AND predator; (B) (stress disorder or depressive disorder or anxiety disorder) AND animal AND social defeat; (C) (stress disorder or depressive disorder or anxiety disorder) AND animal AND single prolonged stress; (D) (stress disorder or depressive disorder or anxiety disorder) AND animal AND chronic unpredictable stress. The review articles were filtered out. The remaining studies were divided into studies not addressing individual differences or studies addressing individual differences (genetic, sex-related, epigenetic, or related to prior experiences).

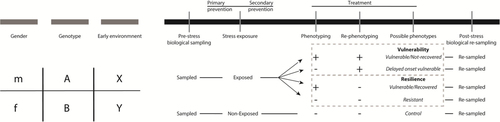

Table 2 Exposure characteristics of the reviewed animal models of PTSD

Fig. 2 Theoretical longitudinal experimental design using an animal model of PTSD. On the left part, three predisposing factors (gender, genotype, and early environment) are depicted on a gray discontinued line which could be examined or controlled for in an animal experiment. In the right black continuous bar, the experimental design includes sampling, stress-exposure, behavioral testing and re-sampling. The time windows for primary/secondary prevention and treatment are also depicted. Pre-stress sampling is important for the discovery of a priori differences that could have predictive value on post-stress phenotypes. Yet, the possible tissue-types for sampling are limited. Stress-exposure depending on the animal model may include a single, repeated or multiple stressors. Behavioral testing should be repeated (phenotyping, re-phenotyping) to evaluate persistence of phenotypes or to detect phenotypes with delayed onset. According to phenotyping/re-phenotyping outcome (–, +) exposed animals can be classified in “Vulnerable/Not-recovered,” “Delayed onset vulnerable,” “Vulnerable/Recovered,” and “Resistant.” Often in literature the terms “Vulnerable/Not-Recovered” and “Delayed onset vulnerable” are merged into the term “Vulnerability” and “Vulnerable/Recovered” and “Resistant” are merged into “Resilience.” Phenotyping/re-phenotyping can differentiate between the overlapping groups. Post-stress re-sampling can be performed after behavioral testing with the advantage of more extensive tissue collection and the disadvantage of the numerous factors (e.g., behavioral testing) that can influence the biological material apart from stress-exposure and group differences.