Figures & data

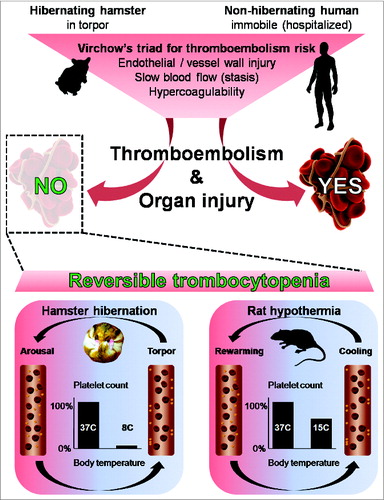

Figure 1. Following Virchow's triad, animals in hibernation are at high risk of thromboembolism and subsequent organ injury, similar to hospitalized humans, subjected to a period of prolonged immobility. Consequently, bedridden patients sooner or later develop thrombosis and embolism with organ injury, whereas hibernating mammals (such as the hamster) do not. Unraveling why they do not suffer thromboembolism, we show that during the repetitive phases of torpor there is a reversible decrease (by 96%) in circulating platelet count (thrombocytopenia). The thrombocytopenia is likely due to margination of platelets to the vessel wall, as depicted in the blood vessel during torpor, which rapidly reverses upon phases of arousal. Similarly, but to a lesser extent, thrombocytopenia can be induced in a non-hibernating mammal by forced hypothermia, also this low platelet count is reversible upon rewarming. Disclosing the shared underlying mechanism in hibernating and non-hibernating species can help us improve anticoagulant control for humans at risk of thromboembolism and organ injury.