?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Abstract

Unsafe abortion is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in Africa. In international human rights law, there are two possible approaches to tackling the problem of unsafe abortion. One is to advocate the right of privacy, which means states must refrain from interfering in women's abortion decisions; the other is to advocate the right to life of women, which stresses the duty of states to take affirmative measures to minimise the consequences of unsafe abortion. African societies are communal and duty is the central element in them. The African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights reflects communal values by stressing the duty of individuals to help their communities. Unlike other human rights documents, it does not have a right of privacy provision. This paper focuses mainly on the right to life and discusses the interpretation of this right for women, as applied to unsafe abortion, under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Advocating states' duties in ensuring women's right to life, to minimise the consequences of unsafe abortion, is more consistent with duty-based African communal values than the right of privacy.

Résumé

L'avortement non médicalisé est l'une des principales causes de mortalité maternelle en Afrique. Dans le droit international humanitaire, deux approches sont possibles pour aborder le problème. L'une est de promouvoir le droit à la vie privée: les Etats doivent s'abstenir d'intervenir dans les décisions des femmes en matière d'avortement. La deuxième est de soutenir le droit des femmes à la vie: les Etats ont le devoir de prendre des mesures pour minimiser les conséquences des avortements non encadrés. Les sociétés africaines sont communautaires et le devoir en est l'élément central. La Charte africaine des droits de l'homme et des peuples reflète les valeurs communautaires en soulignant le devoir des individus d'aider leur communauté. Contrairement à d'autres instruments des droits de l'homme, elle ne contient pas de clause sur le droit à la vie privée. Cet article porte sur le droit à la vie et étudie l'interprétation de ce droit pour les femmes appliqué à l'avortement non encadré, en vertu du Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques. Promouvoir le devoir des Etats d'assurer le droit des femmes à la vie, pour minimiser les conséquences des avortements non encadrés, convient mieux aux valeurs communautaires africaines, fondées sur le devoir, que le droit à la vie privée.

Resumen

El aborto inseguro es una de las causas principales de la mortalidad materna en Africa. La ley internacional de derechos humanos provee dos vı́as posibles para abordar el problema del aborto inseguro. Una de ellas es defender el derecho a la privacidad, lo que significa que los estados deben dejar de entrometerse en las decisiones de las mujeres tocantes al aborto; la otra es defender el derecho a la vida de la mujer, el cual pone hincapié en el deber de los estados de tomar medidas afirmativas para atenuar las consecuencias del aborto inseguro. Las sociedades africanas son comunales y el deber es un elemento central en ellas. La Carta Africana de los Derechos Humanos y de los Pueblos refleja los valores comunales al subrayar el deber de los individuos de ayudar a sus comunidades. A diferencia de otros documentos de derechos humanos, no contiene ninguna provisión para el derecho a la privacidad. Este artı́culo está enfocado en el derecho a la vida y analiza su interpretación como un derecho de la mujer, aplicado al aborto inseguro, bajo el Pacto Internacional de Derechos Civiles y Polı́ticos. Promover el deber del estado de asegurar el derecho a la vida de la mujer para reducir las consecuencias del aborto inseguro es más consecuente con los valores comunales africanos basados en el deber que lo es promover el derecho a la privacidad.

Political attention to the issue of abortion has evolved through three stages of development: first, the law was used to enforce the “moral prohibition of abortion” in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Then, starting in Europe, public health arguments were put forward focusing on women's health and welfare. More recently, safe abortion has been advocated within a human rights and social justice framework, in order to oppose the consequences of criminal barriers to safe abortion Citation[1]. When human rights are discussed in relation to abortion, the focus is usually on the pro-choice/pro-life dichotomy, and the debates are mainly based on the Western assumption of the individualistic nature of social values. In the USA, for example, the court judgement in Roe v. Wade in 1973 which made abortion legal was based on the right to privacy, whereas arguments for prohibiting abortion put forward by the Western pro-life movement have been based on the right to life of the fetus. Attempting to resolve this dichotomy may not effectively address the specific problems of unsafe abortion in Africa, however, where complications of unsafe abortions claim tens of thousands of women's lives annually. Thus, both the pregnant woman and the fetus are killed. In Africa, unsafe abortion and abortion policy affect and concern the whole community.

The issue of unsafe abortion in international human rights law involves several rights, Footnote1 which are protected in various human rights instruments Citation[2]. This article focuses mainly on the right to life and discusses the interpretation of this right, as applied to unsafe abortion, under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) Citation[3].

Human rights: a brief overview

The modern concept of human rights emerged from the devastation of World War II. At the end of the war, contemporaneous with the task of reconstruction, world thinking emphasised respect for individual human rights and health, when the atrocities committed by Nazi Germany were fresh in mind Citation[4]. In 1948, three years after the birth of the United Nations, the General Assembly approved the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Citation[5].

In deciding how to put the principles of the Universal Declaration into legally binding treaties, the then members of the United Nations were divided into two groups Citation[6], a manifestation of the socialist vs. capitalist ideologies of the Cold War era. Governments led by the USA advocated for civil and political rights, while countries led by the former Soviet Union called for economic, social, and cultural rights. For the purposes of accommodating these competing views, the General Assembly finally approved two separate Covenants in 1966, the ICCPR and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) Citation[7].

As the depth of understanding of the concept of human rights grew, the Universal Declaration and the two covenants were followed by various other international and regional conventions. Among those instruments relevant to a discussion of safe abortion are the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (Women's Convention) Citation[8] the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights (African Charter) Citation[9] and the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (European Convention) Citation[10].

ICCPR includes the political and civil rights provided in the Universal Declaration. Most of these rights require states to refrain from arbitrary actions against individual citizens and to take legislative and other measures to ensure the realisation of these rights. In Article 6, for example, ICCPR requires states to respect the right to life of individuals, and in Article 9, to refrain from arbitrary arrest and detention of individuals. The Covenant also protects citizens from torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment under Article 7.

The implementation and enforcement mechanisms of ICCPR depend on the status of a country in the Covenant. States which only sign a treaty (Signatory Parties) are not bound by the treaty unless they ratify it and become `States Parties'. Non-signatory states may be States Parties to a treaty by a single act called `accession', while newly independent countries could also be States Parties to a treaty ratified prior to their independence by `succession'. Currently, 46 African countries Footnote2 are States Parties to ICCPR Citation[11]. According to article 40, States Parties to the Covenant have a duty to submit reports to the UN Secretary General on measures they have taken to realise the rights enumerated in the Covenant. The Secretary General in turn forwards the report to the Human Rights Committee, which is entrusted with overseeing the proper implementation of the Covenant, and which in recent years has ruled on the problems of unsafe abortion in countries. The Committee then studies the reports and responds to the States Parties concerned and if necessary, provides appropriate General Comments on the relevant articles. The States Parties submit to the Committee their observations on its comments.

Under article 41(1) of the Covenant, a State Party may submit a communication (pleading) alleging that another State Party is not fulfilling its obligation under the Covenant (if the latter state recognises the competence of the Committee to consider such a communication). Individuals also have a right to submit a communication, according to articles 2–4, to the Committee against any violation of rights provided in the Covenant if their country is a State Party to the First Optional Protocol to the Covenant Citation[12]. The individuals, however, must exhaust all available remedies before submitting a written communication to the Committee. Considering the admissibility of the communication, the Committee forwards the allegation to the attention of the State Party concerned. The State Party then, within six months, submits to the Committee a written statement explaining the matter and the remedy taken, if any. The communication should not be anonymous. Of the 46 African States Parties to the Covenant, 32 countries Footnote3 are States Parties to the Optional Protocol. This has allowed NGOs to submit communications to the Human Rights Committee on the problem of unsafe abortions.

Two human rights approaches to unsafe abortion

There are at least two strategies using human rights provisions that can be applied to combating the consequences of unsafe abortion. The first advocates the right of privacy and the autonomy of women to have exclusive decision-making power in relation to abortion, in order to limit state interference in the matter (privacy approach). One of the philosophical bases of the privacy approach is that the right to privacy is the right to self-determination, i.e. certain decisions are decisive to the personal identity of an individual, and a state should not be “allowed to interfere with them” Citation[13].

Advocates of the privacy approach stress that it should be the woman and not the state that decides whether or not she should terminate a pregnancy. A number of provisions in various international human rights instruments may be invoked: (i) the right to privacy is found in article 12 of the Universal Declaration and article 17 of ICCPR, and (ii) the right to liberty and security of the person is protected by article 3 of the Universal Declaration, article 9 of ICCPR and article 6 of the African Charter.

The second strategy calls for the involvement of a state and its duty to protect the lives of women who are vulnerable to the fatal consequences of unsafe abortion (life approach). The focal point of this strategy is that the state and the public in general have a responsibility to reduce maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion practices. It can be argued that laws which force women to make use of dangerous procedures to induce an abortion or that allow for the arrest and imprisonment of women having abortions violate the right to life of the women. The bases of the life approach are the human rights provisions that protect the right to life and survival of persons: (i) article 3 of the Universal Declaration, (ii) article 6 of ICCPR, and (iii) article 4 of the African Charter. The life approach maintains that the legality of abortion is only one factor in the complex moral, religious and socio-economic patterns attached to unsafe abortion, and that multi-dimensional measures are needed to make abortion safe.

The work of the Human Rights Committee has been supportive of the second approach to date. In dealing with unsafe abortion, the Committee has repeatedly invoked the right to life provision of ICCPR, article 6, when insisting that states minimise the fatal consequences of unsafe abortion. Although the right-to-life provision historically was meant to require governments to refrain from arbitrarily taking individuals' lives, over time the scope of the right to life has been expanded to include an obligation on the part of states to take appropriate measures to minimise the extent of deaths resulting from socio-economic factors.

In 1982, expressing its concern about the then narrow interpretation of the right to life, the Committee clarified that this right calls for states to adopt positive measures to reduce infant mortality and to increase life expectancy Citation[14]. Similarly, the Committee noted in 1993 that the increasing rate of infant mortality in Romania was a violation of the right to life Citation[15]. In 1999, the Committee held that Canada had a duty under the right to life in ICCPR to take positive measures to address the fatal effects of homelessness Citation[16].

Considering the report of Ecuador in 1998, the Committee extended its interpretation of the scope of the right to life provision to the tragic consequences of unsafe abortion practices. It expressed its concern about the high suicide rate of young pregnant Ecuadorian women, the cause of which was in part a restrictive abortion law and specifically noted that the failure of the state party to address the problem of abortion for rape victims constituted a violation of the right to life Citation[17]. In 1999, regarding the report of Chile, the Committee said:

`The criminalization of abortions, without exception, raised various issues … The State Party is under a duty to take measures to ensure the right to life of all persons, including pregnant women whose pregnancies are terminated' Citation[18].

In discussing the report from Poland in 1999, the Committee regarded strict abortion laws that aggravated clandestine abortion practices to violate the right to life of women who are vulnerable to unsafe abortion practices Citation[19]. The Committee's broad interpretation of the right to life applies to all 46 African countries that are States Parties to ICCPR.

The right to life approach in Africa

Given the reality of African societies and the gravity of the consequences of unsafe abortion in them, it is appropriate to consider using the `life approach' to deal with the problems of unsafe abortion, as this would enable advocates to appeal to their respective governments to remove the legal, economic and social causes of unsafe abortion. African countries that are States Parties to the ICCPR in particular have a duty to take all steps to identify the causes and minimise the consequences of unsafe abortion. Such a duty includes mobilising communities to reduce unwanted pregnancies, educating the public to understand the consequences of unsafe abortion, reconsidering restrictive abortion laws, providing health services that would make abortion safe and other appropriate measures.

The `life approach' is pertinent to Africa for a number of reasons. An estimated five million African women resort to unsafe abortion annually, of which 1,900,000 are in Eastern Africa, 600,000 in Middle Africa, 600,000 in Northern Africa, 200,000 in Southern Africa, and 1,600,000 in Western Africa respectively Citation[20]. Unsafe abortion claims the lives of 34,000 African women annually, making the issue of unsafe abortion in Africa a matter of life and death for women.

The factors that force women to resort to unsafe abortion practice in Africa are complex, and include legal, socio-cultural and economic factors. Most abortion laws inherited from the former colonial powers have remained stagnant for the past four decades, despite the fact that social values regarding sex and pregnancy have greatly changed. The Penal Code of Ethiopia, that prohibits abortion except to save the life of a pregnant woman, for example, was adopted from France in 1957. In France, however, the Abortion Act of 1975 as amended in 1979 permits abortion on request during the first trimester of pregnancy Citation[21]. In contrast, the Ethiopian Penal Code has not been amended.

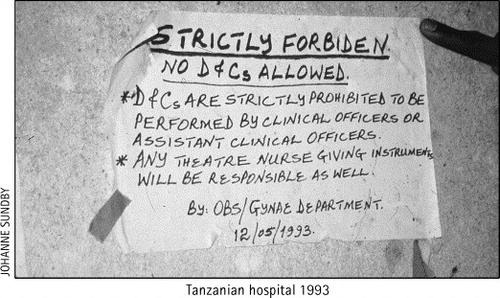

Some African countries permit abortion on grounds such as rape and incest, but these are permitted on paper only, e.g. in the Penal Code of Eritrea Citation[22]. Footnote4 These laws lack detailed guidelines specifying the procedures that a victim, law enforcement officials, and health professionals should follow for an abortion to be performed, and the uncertainty allows concerned bodies to deny abortion access to rape victims in order to avoid the risk of criminal liability.

From a socio-cultural point of view, in many parts of Africa life is structured around communal roles and responsibilities, rather than the wishes of the individual Citation[23], and the day-to-day activities of individuals and their extended families are intertwined. Co-operation and collective responsibility are the basic values of African societies Citation[23]. Individuals have a duty to play a significant role to improve the life of their community, which in turn assumes a duty to protect its members. The concept of `duty' greatly outweighs that of `right of privacy' in such socio-economic settings. The African Charter reflects this by stressing the duty of individuals in various articles. Chapter II of the Charter sets out three provisions (articles 27–29), requiring individuals to help their family, community, society and state. The requirement of individual duty is one of the unique characteristics of the African Charter, compared to other international human rights instruments.

In contrast to the other regional human rights instruments, the African Charter does not have an article that expressly provides the right to privacy of individuals. The absence of this provision reflects traditional communal values. Some articles of the Charter may imply the notion of privacy, such as article 5 (right to the respect of the dignity inherent in a human being) and article 6, (right to liberty and security of the person). However, the overall emphasis of the Charter, compared to similar regional human rights documents, is to protect communities and societies at large. Article 18(2) of the Charter, for example, defines the family as “the custodian of morals and traditional values recognised by the community”.

Other relevant human rights provisions and instruments

Article 6 of ICCPR requires States Parties to take affirmative measures to reverse the tragedy of unsafe abortion. Using the interpretation of the Human Rights Committee, advocates can urge African states to take affirmative measures to minimise maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion. They may also invoke relevant provisions in other international human rights instruments to which a country is a State Party, a number of which directly or indirectly relate to the consequences of unsafe abortion, especially those expressly dealing with the right to health. The ICESCR (article 12) and African Charter (article 16), for instance, require States Parties to ensure the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. The ICESCR Footnote5 and the African Charter Footnote6 have 44 and 53 States Parties respectively Citation[24]Citation[25].

Similarly, the Women's Convention (article 12 and 14(2)(b)) lays down states' duty to provide access to appropriate health services and facilities, including information, counselling and services in the area of family planning. The Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women affirmed article 12 of the Women's Convention to be central to women's well-being. The Committee requires States Parties to the Convention to ensure “access to health care services … particularly in the areas of family planning, pregnancy and confinement and during the post-natal period” Citation[26].

Individuals or institutions on behalf of individuals can submit a communication against any alleged violation of the rights set out in the Women's Convention. The country against which the communication is submitted must be a State Party to both the Convention and the Optional Protocol to the Convention (Optional Protocol) Citation[27]. Of the African countries which are States Parties to the Convention Citation[28], three are States Parties to the Optional Protocol Citation[29]. Footnote7

The status of the fetus in human rights law

The `life approach' is likely to be more relevant and acceptable than the `privacy approach' to tackling the consequences of unsafe abortion in Africa, because it is responsive to the complex causes of the problem in the continent. An inevitable legal issue related to the `life approach', however, is the legal status of the prenatal entity (fetus) under international law, i.e. whether or not a fetus is a person recognised to have a right to life according to article 6 of the ICCPR.

The legal status of a fetus has never been a central issue in abortion cases in any of the UN human rights bodies. Regional human rights organisations and most national courts are reluctant to discuss the issue of personhood of a fetus. The European Commission on Human Rights has decided very few abortion cases but it has never discussed this issue. In Paton v. United Kingdom Citation[30], Mr. Paton forwarded his application to the European Commission, pleading that a High Court decision that permitted abortion violated article 2(1), Footnote8 the right to life of the fetus, under the European Convention. The Commission declined to discuss the issue of whether article 2 of the Convention protects a fetus or not. Instead, it said that whether a fetus was recognised to have the right to life had not been “considered by the Commission in any other case Citation[30]”. In Roe v. Wade, the US Supreme Court expressly refrained from determining the status of a fetus. It stated:

`[w]e need not resolve the difficult question of when life begins. When those trained in the respective disciplines of medicine, philosophy, and theology are unable to arrive at any consensus, the judiciary, at this point in the development of man's knowledge, is not in a position to speculate as to the answer Citation[31].'

Similarly, the Canadian Supreme Court, in the leading abortion case, said that the issue whether or not the word `everyone' under Section 7 Footnote9 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms included a fetus “was not dealt with” Citation[32].

Conclusion

A large number of African women resort to unsafe abortion in order to respect the values of their community. The reasons that render a pregnancy `unwanted' may include, for instance, to avoid the social stigma of pre-marital sex and pregnancy. In such a case, even if the law permits abortion, a woman may still resort to unsafe abortion in order to keep her transgression of social values secret.

The consequences of unsafe abortion and the gravity of maternal mortality in Africa are of great concern. Even if laws were liberalised, poverty would still pose an important obstacle to access to abortion services, unless the state ensures that abortion services are not only available, but also affordable and accessible. The `privacy approach' may therefore not be an effective strategy in Africa. Economic constraints and negative social values, which lead African women to resort to unsafe abortion, call for the involvement of states in resolving the problems, rather than leaving the matter to women alone. Insisting that states take affirmative measures is indispensable in tackling the multi-dimensional causes of unsafe abortion, making the `right to life of women approach' a more effective strategy.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Professors Rebecca Cook and Bernard Dickens, Faculty of Law University of Toronto, and Charlotte Hord of Ipas for their valuable advice and comments on this article.

Notes

1 Of the common `rights' invoked in abortion discourses are: right to life and survival; right of privacy, liberty, and security; right to benefits of scientific progress; right to private and family life; and right to non-discrimination on grounds of sex and gender. See Citation[2].

2 The States Parties are: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopian, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe. See Citation[11].

3 The States Parties are: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Lesotho, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritius, Namibia, Niger, Norway, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia. See Citation[11].

4 Article 534(1) says: “Termination of pregnancy is not punishable where it is done to save the pregnant woman from grave and permanent damage to life or health, or on account of an exceptionally grave state of physical or mental distress following rape or incest.” [Translated from Proclamation no. 4 in local language, Tigrinya].

5 The States Parties of ICSECR include: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. See Citation[24].

6 Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Comoros, Congo, Congo (RD), Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Uganda, Rwanda, Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, S o Tomé & Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Chad, Togo, Tunisia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. See Citation[25].

7 The following countries are States Parties to the Women's Convention: Algeria, Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe. The States Parties to the Optional Protocol are Mali, Namibia, and Senegal. See Citation[27].

8 The article provided that: “… No one shall be deprived of his life intentionally save in the excess of a sentence of a court following his conviction of a crime for which the penalty is provided by law.” See Citation[10].

9 Section 7 of the Canadian Charter says, “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” See Citation[31].

References

- R.J. Cook, B.M. Dickens, L.E. Bliss. International developments in abortion law from 1988 to 1998. American Journal of Public Health Law. 89(4): 1999; 579.

- R.J. Cook, B.M. Dickens. Considerations for formulating reproductive health laws. 2nd ed, 2000; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 19 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171, reprinted in 6 ILM 368, 1967 (entered into force 23 March 1976)

- L.P. Freedman. Human rights and women's health. M. Goldman, M. Hatch. Women and Health. 2000; Academic Press: San Diego, 428–431.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res. 217(III), UN GAOR, 3d Sess., Supp. no. 13, UN Doc. A/810 (1948) 71

- C. Devine, C.R. Hansen, R. Wilde. Human Rights. H. Poole, V. Tomaselli. 1999; Oryx Press: Phoenix, 63.

- International Covenant in Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 16 December 1966, 993 UNTS 3, reprinted in 6 ILM 360, 1967 (entered into force 3 January 1976)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 18 December 1979, 1249 UNTS 20378 (entered into force 3 September 1981)

- African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, 27 June 1981, OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/67/3/Rev. 5, reprinted in 21 I.L.M. 58, 1982 (entered into force 21 October 1986). Article 18(2)

- Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 4 November 1950, 213 UNTS 221, Eur. TS 5 (entered into force 3 September 1953). Article 8

- United Nations, Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary-General. Available from: http://untreaty.un.org/ENGLISH/bible/englishinternetbible/partI/chapterIV/treaty6.asp. Last modified 15 February 2002

- Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 23 March 1966, 999 UNTS 171 (entered into force 23 March 1976)

- J. Rubenfeld. The right to privacy. Harvard Law Review. 102: 1989. 737, 753.

- High Commission for Human Rights, The right to Life (art. 6) [ ] CCPR General Comment 6, 16th Sess., UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Add. I. (1982) at 2, para 5

- Human Rights Committee, Concluding Comments of the Human Rights Committee: Romania, UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add. 30 (1993) para. 11

- Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Canada, 65th Sess., UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add. 105 (1999) para. 12

- Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Ecuador, 63rd Sess., UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add. 92 (1998) Para. 11 and 15

- Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Chile, 65th Sess., UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add. 104 (1999) para. 15

- Human Rights Committee, Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee: Poland, 66th Sess., UN Doc. CCPR/C/79/Add. 110 (1999) para. 11

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of incidence of and mortality due to unsafe abortion with a listing of available country data, 3rd ed., WHO/RHT/MSM/97.16, Geneva, 1998. p. 8

- Code de la Santé Publique, JO, 1 January 1980, c 3, as am. by Art. 4, Law No. 79-1204, Art. L.162-1, Available from: Harvard Law School http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/population/abortion/France.abo.htm. Last modified 13 September 2000

- Transitional Penal Code of Eritrea, Penal Code of the Empire of Ethiopia, Proclamation No. 158, 1957, as am. by Proclamation of Eritrea No. 4, 1991, art. 534(1)

- J. Swanson. The emergence of new rights in the African Charter. New York Law School Journal of International and Comparative Law. 12: 1991; 307–328.

- United Nations, Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary-General. Available from: http://untreaty.un.org/ENGLISH/bible/englishinternetbible/partI/chapterIV/treaty4.asp. Last modified 15 February 2002

- Human Rights Library, List of countries who have signed, ratified/adhered to the African Charter on Human and People's Rights. Available from: http://heiwww.unige.ch/humanrts/instree/ratz1afchr.htm. (Last modified 4 June 2000)

- See generally, Women and Health: CEDAW General recom. 24 (General Comments), General Recommendation No. 24, UN Doc. A/54/38/Rev. 1, Chapter I, (1999), UN Doc. A/54/38/Rev. 1, Chapter I, Available from: UNHCHR, http://www.unhchr.ch/tbs/doc.nsf/(symbol)/CEDAW+General+recom.+24.En?OpenDocument. Accessed 25 February 2002

- Option Protocol to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 2 December 2000, UN Doc. A/RES/54/4 (entered into force 22 December 2000)

- United Nations, Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary-General. Available from: http://untreaty.un.org/ENGLISH/bible/englishinternetbible/partI/chapterIV/treaty9.asp. Last modified 15 February 2002

- United Nations, Multilateral Treaties Deposited with the Secretary-General. Available from: http://untreaty.un.org/ENGLISH/bible/englishinternetbible/partI/chapterIV/treaty11.asp. Last modified 15 February 2002

- 1980, 3 Eur. Comm. HR DR 408. p. 412

- Wade Rv. 410 US 113 (1973) at 159

- Morgentaler Rv. 1988 1 SCR 30 at 38. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c. 11