Abstract

Abstract

Thanks to initiatives since 1994, most reproductive health programmes for refugee women now include family planning and safe delivery care. Emergency contraception and post-abortion care for complications of unsafe abortion are recommended, but provision of these services has lagged behind, while services for women who wish to terminate an unwanted pregnancy are almost non-existent. Given conditions in refugee settings, including high levels of sexual violence, unwanted pregnancies are of particular concern. Yet the extent of need for abortion services among refugee women remains undocumented. UNFPA estimates that 25–50% of maternal deaths in refugee settings are due to complications of unsafe abortion. Barriers to providing abortion services may include internal and external political pressure, legal restrictions, or the religious affiliation of service providers. Women too may be pressured to continue pregnancies and are often unable to express their needs or assert their rights. Abortion advocacy efforts should highlight the specific needs of refugee women and encourage provision of services where abortion is legally indicated, especially in cases of rape or incest, and risk to a woman's physical and mental health. Implementation of existing guidelines on reducing the occurrence and consequences of sexual violence in refugee settings is also important. Including refugee women in international campaigns for expanded access to safe abortion is critical in addressing the specific needs of this population.

Résumé

Grâce à des initiatives menées depuis 1994, la plupart des programmes de santé génésique pour réfugiées incluent désormais la planification familiale et les soins obstétriques. La contraception d'urgence et le traitement des complications d'avortements non encadrés sont recommandés, mais ces services tardent à venir, alors que les services pour les femmes souhaitant interrompre une grossesse non désirée sont presque inexistants. Compte tenu des conditions de vie des réfugiés, notamment les niveaux élevés de violence sexuelle, les grossesses non désirées sont particulièrement préoccupantes. Pourtant, on n'a pas évalué le besoin de services d'avortement chez les réfugiées. Le FNUAP estime que dans les sites de réfugiés, 25–50% des décès maternels sont dus aux complications d'avortements non encadrés. Les obstacles aux services d'avortement incluent des pressions politiques internes et externes, des restrictions juridiques ou l'appartenance religieuse des prestataires de services. Les femmes sont aussi incitées à poursuivre leur grossesse et se révèlent souvent incapables d'exprimer leurs besoins ou de faire respecter leurs droits. Les efforts en faveur de l'avortement doivent cerner les besoins des réfugiées et encourager la prestation de services quand l'avortement est juridiquement indiqué, particulièrement en cas de viol ou d'inceste, et de risque pour la santé physique ou mentale de la femme. L'application des directives sur la réduction de la violence sexuelle et de ses conséquences dans les sites de réfugiés est également importante. Pour satisfaire les besoins des réfugiées, il est essentiel de les associer aux campagnes internationales prônant un accès élargi à un avortement sûr.

Resumen

Gracias a iniciativas impulsadas desde 1994, la mayorı́a a de los programas de salud reproductiva para mujeres refugiadas incluyen la planificación familiar y la atención al parto. Para las complicaciones de abortos practicados en condiciones de riesgo se recomiendan la anticoncepción de emergencia y la atención post-aborto, pero la provisión de estos servicios ha quedado rezagada mientras que los servicios para las mujeres que quieren terminar un embarazo no deseado a penas existen. Dadas las condiciones en que se encuentran las refugiadas, donde los niveles de violencia sexual suelen ser altos, los embarazos no deseados son especialmente preocupantes. Sin embargo no está documentada la demanda de servicios de aborto entre mujeres refugiadas. FNUAP calcula que entre el 25 y el 50 por ciento de las muertes maternas de refugiadas se debe a las complicaciones de abortos inseguros. La provisión de servicios de aborto puede estar obstaculizada por presiones polı́ticas internas y externas, restricciones legales, o la afiliación religiosa de los proveedores de dichos servicios. Las mujeres pueden estar presionadas para continuar sus embarazos sin poder expresar sus necesidades ni exigir que se les respeten sus derechos. Al promover la disponibilidad de servicios de aborto sin riesgo se debe hacer hincapié en las necesidades especı́ficas de las mujeres refugiadas e impulsar la provisión de dichos servicios en las circunstancias en que el aborto esté legalmente indicado, especialmente en casos de violación e incesto, y riesgo de daños a la salud fı́sica y mental de la mujer. Es igualmente importante implementar las pautas existentes para reducir tanto la violencia sexual a que estén expuestas las refugiadas como sus consecuencias. Al abordar las necesidades especı́ficas de esta población, es preciso incluir a mujeres refugiadas en las campañas internacionales a favor de ampliar el acceso al aborto seguro.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that as of 1999 there were over 22 million documented refugees worldwide, as well as numerous internally displaced persons (IDPs) who have also been uprooted from their homes but remain within their national boundaries and are not accorded legal refugee status. Many of the challenges regarding health care needs and provision are common to both populations; hence, in this article both refugee and IDP populations will be termed “refugees” Citation[1].

Where is abortion in reproductive health care for refugees?

In 1994, health services for refugees took a dramatic and long-awaited turn. Representatives of relief agencies gathered with reproductive health specialists to address the reproductive health needs of refugee women, and discuss how best to include those needs in the delivery of traditional primary health care services for refugee populations. This move was supported by the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, which called for the inclusion of reproductive health services in primary health care systems and offered specific guidance for integrating women's health care needs into refugee programmes. With this global impetus, needs assessments were conducted and implementation packages and guidelines were created to illustrate how relief organisations could include reproductive health for refugees in their health strategies and programmes.

Today, eight years on, refugee women's access to family planning has undoubtedly increased, and programmes focusing on safer deliveries in refugee settings have expanded, with emergency obstetric services for complications of pregnancy and delivery slowly making their way into refugee health planning Citation[2]Citation[3]. Many organisations recognise that the reproductive health needs of refugees still far outweigh available services, but with the leadership of the headquarters and regional offices of UNHCR, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), UNICEF and other key international players, progress has been made to improve the ability of refugee women to plan their families and receive pregnancy care.

The problem with this mostly positive picture is that these efforts focus primarily on childbirth as the pregnancy outcome. Although reproductive health recommendations for refugees include emergency contraception for women who want to avoid pregnancy after rape or contraceptive failure, and post-abortion care (PAC) for women suffering complications of unsafe or spontaneous abortion, provision of such services has lagged far behind Citation[4], while services for women who wish to terminate an unwanted pregnancy are almost non-existent.

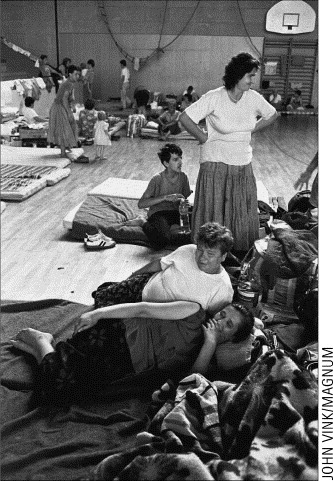

Unwanted pregnancy occurs everywhere, but it is of special concern in refugee settings. Refugee women are among the most vulnerable of at-risk populations. In addition to being displaced from their place of origin and temporarily homeless, refugee women lack protection in the social and physical milieu where they find themselves, are often separated from family and partners and may continuously be targets for violence. Increasingly, rape is being documented as a weapon of war, affecting women in many countries, including the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Bangladesh, Uganda, Myanmar and Somalia Citation[5]. Violence against refugee women can take place at any time during social disruption and flight, and is committed by military troops and police, fellow refugees, border guards and others. Unfortunately, a refugee settlement is commonly not a safe haven. Refugee settings tend to be resource-poor environments and once settled, many women are forced to use sex as a means of supporting themselves and their dependents and children. Cases of women being forced to exchange sex for food, being raped while seeking firewood, and having to submit to sex in exchange for protection are all well documented in refugee settings Citation[5]Citation[6]Citation[7]. In addition, increased levels of domestic violence and marital rape among refugee women have been reported Citation[3]Citation[5].

High exposure to frequent, forced and unprotected sex clearly puts refugee women at high risk of unwanted pregnancy. Additionally, refugee women often have limited or interrupted access to contraception and little or no access to emergency contraception. Even where emergency contraception is available, women may not know about it and provider knowledge of its use may be low, or supplies limited Citation[3].

Experience supports the need for safe abortion services among refugee women. In Tanzania, where the abortion law is highly restrictive, a doctor at one health centre received five requests a day for abortion from Rwandan refugees in the year following the 1994 civil war Citation[8]. In situations as varied as Thailand, Guatemala and Somalia, refugee clinic admissions for complications of unsafe abortion have been reported Citation[2]. In 1999, two Kenyan refugee camps implemented PAC services for treatment of complications on site. In one camp with a total population of 115,000, six women a month were given emergency PAC. The second camp, with a population of 64,000 treated on average nine women a month for PAC. Given that only a small percentage of women with abortion complications are able to seek treatment, i.e. those who know where services are available and have access to transport and familial or other support, it is likely that these numbers represent only a fraction of the true need Citation[9]. UNFPA estimates that 25–50% of maternal deaths in refugee settings are due to complications of unsafe abortion Citation[10].

Why is safe abortion left out?

Although access to safe abortion services should be part of any comprehensive reproductive health care package, this is rarely the case in refugee health care for a variety of reasons. First, there is a paucity of hard data on the abortion-specific needs of women in refugee settings. Many organisations do not collect such data, and in any case, it is rarely published. Without data to demonstrate need, programming rarely follows. Furthermore, with a primary health care and relief focus, many organisations working primarily with refugees do not prioritise broader reproductive health needs. At the implementation level, the ambiguity of local law and medical practice similarly create barriers. Women seeking refuge in a foreign country may be unaware of when abortion is permitted under local law and may have limited or no information about the availability of safe, legal abortion care. Health care practitioners working in refugee settings in countries where the law is restrictive also may not be fully informed of broader indications for abortion, such as in the case of rape and incest, or may not understand how a broader interpretation of protecting physical and mental health would permit them to provide a legal abortion. Furthermore, many refugee clinics are not organised for abortion services, meaning abortion would only be offered at a referral centre located off-site. Even where referral services exist, gaining access to them could still be a problem because of transport, organisational, financial or communication difficulties. Furthermore, as many relief agencies are religiously affiliated, religious standards and practice could represent a barrier as well.

Refugee settings may also be heavily politicised. Internal politics may lead to restrictions on services for refugees in an effort to ease tensions between the host country and refugee populations, or to hasten the return of refugees. In Croatia, for example, refugee women were not legally entitled to the full range of health services available from the public health system to the local population Citation[11]. External political pressure may also play a role, as seen recently in statements on the Vatican Radio accusing UNFPA reproductive health programmes of promoting abortion in a high visibility Afghan refugee setting Citation[12]. Such situations place refugee women in the middle of a debate that has little to do with their individual needs or rights.

Finally, few refugee women are in a position to demand services in spite of obvious need. Refugee women may face societal pressure to bring a pregnancy to term to replace lost family or clan, or to hide the fact that a pregnancy is the result of rape or trading sex for food and goods, which would be stigmatising if discovered Citation[7]. Additionally, many refugee women are fleeing repressive governments and have little or no experience of expressing their needs or demanding their rights. Individual advocacy is very difficult in such settings. Furthermore, the dynamics of refugee status, including limited resources, overwhelming daily life challenges and the transitory situation of refugee settings can restrict refugee women from organising themselves into a broader activist coalition.

What can be done?

Internationally, supporters of increased access to abortion services must advocate for the needs of refugee women. Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), reproductive health organisations and government health officials working with refugee populations have a responsibility to inform themselves of the need for abortion services among refugee women, the availability of abortion services for them and local abortion law and practice. It is particularly important to look at how the law is most relevant to refugee women's situation, such as where abortion is permitted to protect a woman's health, or following rape or incest. Collecting data on the need for safe abortion and the number of unsafe abortions among refugee women is critical to helping refugee women receive the care they need and want.

At refugee camps or settlement areas, additional advocacy efforts are necessary. Refugee women have the right to information and confidentiality Citation[11]. Organisations and individuals must work to inform refugee women of their right to abortion care, where indicated, and must work to provide access to such care in a confidential manner. Reducing the occurrence and consequences of violence against refugee women through enforcement of UNHCR guidelines on prevention and response to sexual violence in refugee settings should be an integral part of humanitarian efforts Citation[6]. At a minimum, accessible contraceptive services and emergency contraception should be treated as an obligation of health service providers in refugee settings. In all sites, but especially where safe abortion services are not available, treatment for complications of unsafe abortion must be an integral part of on-site health delivery in refugee camps.

Advocacy should lead to services

Whereas the 1994 ICPD Programme of Action created a link between reproductive health and refugees, ICPD+5 highlighted further recommendations for abortion care that should be the basis of planning health care for refugee women:

`… in circumstances where abortion is not against the law, health systems should train and equip health service providers and should take other measures to ensure that such abortion is safe and accessible.' Citation[13]

Advocacy groups should share this message with organisations and governments providing health care to refugee populations and promote its implementation through increased training of refugee health care providers in carrying out abortion, expansion of appropriate technology for induced abortion to refugee settings and links to contraceptive services. Where organisational, logistical or religious constraints are barriers to refugee women's access to legally indicated abortion, organisations must be encouraged to partner with other agencies or government health services to create availability and access to safe abortion services for refugee women.

Finally, refugee women must be given a forum so that their voices are heard on this and related reproductive health issues. Their experiences and perspectives will broaden the international dialogue for expanded global access to safe abortion through awareness of the specific needs of this diverse population.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Refugees and others of concern to UNHCR 1999 statistical overview. Geneva: UNHCR, 2000

- Reproductive Health for Refugees Consortium. Refugees and reproductive health care – the next step. New York, 1998

- L Goodyear, T McGinn. Emergency contraception among refugees and the displaced. JAMWA. 53(5/Suppl 2): 1998; 266–270.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Reproductive health in refugee situations: an interagency field manual. Geneva: UNHCR, 1999

- L Shanks, M Schull. Rape in war: the humanitarian response. CMAJ. 163(9): 2000; 1152–1156.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Sexual violence against refugees: guidelines on prevention and response. Geneva: UNHCR, 1995

- C Palmer, A Zwi. Women health and humanitarian aid in conflict. Disasters. 22(3): 1998; 236–249.

- Sommer A. Massale verkrachtingen in Ruanda: “Mijn zwangerschap is een marteling”. [Mass rape in Rwanda: `My pregnancy is torture']. Onze Wereld 1995; May 24–25

- Onyango S, Orero S. Final report Kenya refugee PAC project. November 2000, unpublished

- UN Populations Fund. Reproductive health for refugees and displaced persons. The State of the World's Population. New York: UNFPA, 1999

- C Shalev. Rights to sexual and reproductive health: the ICPD and the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. Health and Human Rights. 4(2): 2000; 38–66.

- UN Population Fund. UN Population Fund refutes Vatican Radio's baseless charge that it promotes abortion among Afghan refugees. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/news/2002/pressroom/abortion.htm. Accessed 18 January 2002

- United Nations. Key actions for further implementation of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development. New York: UN, 1999