For women attempting to have a son and experiencing pressure to fulfil their `womanly duty' by having a male child, sex selective abortion can be extremely empowering. Through choosing to terminate a pregnancy when the fetus is female or to carry on with it if the fetus is male, women in many Asian societies can gain legitimacy, earn recognition and acquire status in their family and community. By using sex selective abortion, women may avoid having more children than they want and thus limit the size of their family.

In a village study on son preference that I conducted with Vietnamese colleagues in rural north Viet Nam in 2000, virtually all families with four or more children were composed of daughters only Citation[1]. These large families suffered acute poverty due to small land holdings and the high cost of education. All families of the village continued to have children until a son was born. Those who had a son stopped after two children and enjoyed the social and economic benefits of having a small family. In sonless families, women and daughters suffered the burden of not having a male heir among them.

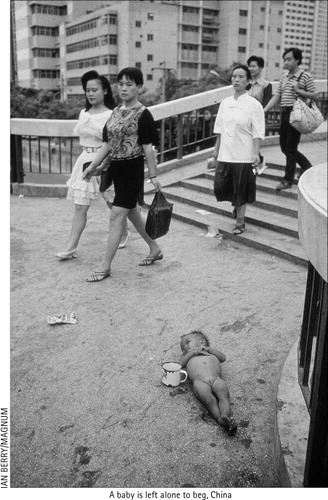

Illtreated and stigmatised sonless women were found in this village as they were in many other villages of Asia where son preference prevails. In a few cases, unwanted daughters were given up for adoption or died in early infancy.

Research has shown that daughters of high birth orders are more likely to be discriminated against than other daughters Citation[2]. Due to this mechanism, Goodkind argues that forbidding sex selective abortion could potentially increase discrimination of unwanted girls in the postnatal period Citation[3]. In our study, daughters in large sibling sets of three or more suffered to a greater extent than girl children in smaller families. They were aware that their parents continued childbearing in an attempt to have a son in spite of sanctions (fines and penalties) for violating Viet Nam's two-child policy and increased poverty. In these large families, poverty obliged daughters to interrupt their schooling, although parents and daughters perceived education to be girls' only way out in a world that is harsh to females. Teenage daughters that I interviewed were struggling to make sense of their parents' desperate attempts to bear a son.

All the sonless women I interviewed were seeking ways to exert some control over the sex of their children. While abortion is widely available in Viet Nam, there is no indication that widespread sex selective abortion is practised. According to the last census, conducted in 1999, the sex ratio at birth was 105:100 Citation[4]. In the village where my study was done, women knew about ultrasound technology but believed it was not possible to determine the sex of the fetus until after five months of pregnancy. Second trimester abortions are difficult to obtain in Viet Nam, making sex selective abortion by that time even more difficult to envision. As an alternative, sonless women turned to traditional medicine and healers, spent a fortune and travelled many kilometers in an effort to increase the likelihood of producing a son. Some families faced accrued poverty due to the cost of some of these treatments. While I did not find any clear evidence of sex selective abortion in that village, it is possible that rural women will soon be resorting to it. Recent hospital data point to the existence of sex selective abortion in Hanoi, Citation[4] which is likely to spread to rural areas in the years to come. While family planning has given women a means of controlling the number of children they want to have, they feel betrayed that they must limit the size of their families to two or three children, yet also produce a son. To be sure, women suffer a great deal from the clash between the high demand for sons and the low demand for children, and sex selective abortion has the power to free them from such contradictory internal desires and external pressures. For the moment, most Vietnamese women, particularly the youngest ones, have to struggle with these competing demands on their fertility.

Viewing sex selective abortion as strictly empowering is unquestionably shortsighted. Sex selective abortion is a powerful tool by which gender inequalities are perpetuated and reproduced, not only by male and senior (male and female) family members who put pressure on women, but also by women themselves needing to guarantee their status and position in their family and community. Sex selective abortion, while empowering women in the short term, will most likely continue to further threaten their position in the long term. One factor of this long-term outcome is demographic.

Sex selective abortions create an imbalance in the sex structure of populations. Once this imbalance reaches marriageable age groups, a shortage of women poses serious problems, particularly in societies where marriage is a nearly universal norm. In the early 1980s, when sex selection of children began to get attention, demographer Nathan Keifitz predicted that “if as a result of sex selection women become fewer, their relative position will change” Citation[5]. Keifitz predicted that sex selective abortion held the potential to reduce gender inequalities by making women fewer and thus more powerful. So far, however, research does not indicate any trend in that direction. If anything, I believe that in societies where gender inequalities are high, a shortage of women will be detrimental to women's well-being. Guttentag and Secord's Citation[6] important work on this issue identified potential consequences of a shortage of women, such as increased violence (or even war due to a shortage of brides) and a decline in women's political power (less of them to vote).

Discouraging the perpetuation of gender inequalities through sex selective abortions by taking legal action has not been successful so far. Going back to the case of Viet Nam, sex selective abortion cannot be fought there, as in other countries, unless fundamental social changes take place. The legal battle will never be successful unless parents have incentives to desire daughters. Sons are generally preferred for three reasons: they hold a high symbolic value, given the importance of carrying on the family line; they hold a high social value because they give status and legitimacy to adults who have them; and, finally, they hold economic value, since they are responsible for their parents in old-age and generally have more earning power than daughters. Returns from sons take numerous forms and surpass those that daughters may provide. The examples of South Korea and Taiwan indicate the pervasiveness of the symbolic value of sons. They illustrate that socio-economic development, low fertility and women's improved position in society do not necessarily contribute to reducing gender inequalities among children or the `gendered' reasoning attached to girls and boys. Policy initiatives focusing on the girl child are absolutely necessary. Programmes aimed at increasing daughters' self-esteem and self-assertiveness, among other initiatives, would better equip women to reflect upon their reproductive choices and decisions when they become mothers.

In sum, I am in agreement with Oomman and Ganatra's opposition to sex selective abortions. But to blame the medical community for its economic motives and senior and male family members for exerting pressure on women prevents us from recognizing that women, too, are extremely motivated to have sons and may resort to sex selective abortion to do so. While women's choices and decisions are clearly not primarily individual, women's agency cannot be evacuated. Women's motivations for undergoing sex selective abortions are perfectly legitimate, given the kinship system in which they marry, have children, and become elderly. Increasing daughters' value may be the only sustainable and viable option for winning the battle against sex selective abortion. Whenever arguing against sex selective abortion, also advocating for the value of daughters to parents for the sake of today's daughters and daughters-to-be born is constructive, realistic and imperative, as Croll forcefully argues Citation[7].

Fundamental changes in children's gender roles will take time, but are the only effective way to reduce the strong demand for sex selection of children. In the meantime, today's mothers struggle for their identity and survival and sex selective abortions can help them in that struggle. In spite of the costs of sex selective abortions, the payoffs it offers in their daily lives largely justify their actions.

References

- Bélanger D. Son preference and demographic change in Viet Nam. In: Paper presented at International Conference, International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, August 2001, Brazil

- M. Das Gupta, P.N.M. Bhat. Fertility decline and increased manifestation of sex bias in India. Popul. Stud. 51: 1997; 307–316.

- D. Goodkind. Should prenatal sex selection be restricted? Ethical questions and their implications for research and policy. Popul. Stud. 53: 1999; 49–61.

- Bélanger D, Khuat TO. Are sex ratios at birth increasing in Vietnam? (unpublished manuscript, 2002)

- N. Keifitz. Forward. N.G. Bennett. Sex selection of children. 1983; Academic Press: New York, xi–xiii.

- M. Guttentag, P.A. Secord. Too many women: the sex ratio question. 1983; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills.

- E. Croll. Endangered daughters. Discrimination and development in Asia. 2000; Routledge: London. [p. 207].