?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Health sector reforms in China, instituted starting in 1985, have centred on cost recovery, with fee-for-service revenue replacing public budget funding. The share of public funding for maternal health services was reduced greatly, forcing an increasing proportion of pregnant women to pay for deliveries and treatment of pregnancy-related complications out of pocket, as most had no health insurance to cover these costs. This study aimed to identify socio-economic variables associated with utilisation of essential maternal health services and linked to health sector reforms in China, with a focus on cost recovery. A retrospective household survey (n=5756) was carried out in six counties in three provinces of Central China in 1995. Antenatal service utilisation continued to improve in 1990–95, but only in relation to the number of visits, which were pre-paid if the woman was participating in a maternal pre-payment scheme or covered by another health insurance scheme. Significant decreases were found in the utilisation of skilled attendance at delivery and hospital delivery, as well as differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes (miscarriages and stillbirths) between women paying out of pocket and those covered by insurance. This study confirms a strong association between utilisation of delivery services and financing variables of amount of savings in the bank, maternal pre-payment schemes and health insurance. It also shows the critical importance of out of pocket, fee-for-service payments for maternity care as a barrier to the utilisation of these services.

Résumé

Les réformes du secteur de la santé en Chine, commencées en 1985-89, se sont centrées sur la récupération des coûts, la rétribution des services remplaçant le financement public. Une enquête rétrospective auprès de ménages (n=5756) a été menée en 1995 dans six comtés de trois provinces de Chine centrale. L’utilisation des services prénatals a continué de s’améliorer en 1990-95, mais seulement par rapport au nombre de visites, qui étaient prépayées si la femme participait à un plan de prévoyance maternelle ou couvertes par une autre assurance maladie. Des diminutions notables ont été observées dans le recours à une aide qualifiée lors de l’accouchement et des services obstétriques hospitaliers, ainsi que des différences dans les issues négatives de la grossesse (fausses couches et mortinatalité) entre les femmes payant les soins de leur poche et celles qui étaient couvertes par une assurance. Cette étude confirme une nette association entre l’utilisation de services obstétriques et les variables financières que sont les comptes d’épargne, les plans de prévoyance maternelle et l’assurance maladie. Elle montre également que la rétribution personnelle des soins obstétriques est un obstacle à l’utilisation de ces services.

Resumen

Las reformas del sector salud instituidas en China a partir de 1985 se han centrado en la recuperación de costos, con el pago de honorarios por servicios prestados reemplazando el financiamiento público como fuente de ingresos. En 1995, se hizo una encuesta retrospectiva de hogares (n=5756) en seis condados en tres provincias de la China Central. La utilización de los servicios antenatales seguı́a mejorándose en 1990-95, pero solamente en relación al número de visitas, las cuales se pagaban con anticipación si la mujer participaba en un plan de pago prospectivo para los servicios de maternidad o si estaba cubierta por otro tipo de seguro de salud. Se encontraron reducciones significativas en la utilización de personal calificado para la atención de partos y para los partos en hospital, además de diferencias en los resultados de los embarazos (abortos espontáneos y nacidos muertos) entre las mujeres cubiertas por un seguro y aquellas que pagaban honorarios por su cuenta. Este estudio confirma que existe una fuerte asociación entre la utilización de los servicios de maternidad y los variables de financiamiento tales como cuentas de ahorro, planes de pago prospectivo, y seguros de salud. Muestra también que el pago de honorarios por los servicios de salud materna es un obstáculo crı́tico para la utilización de dichos servicios.

In the first ten years of the People’s Republic of China (1949–1959), maternal mortality in Beijing is said to have been brought down from as high as 700 per 100,000 live births before 1949 to 15 per 100,000. Although these statistics may not be entirely reliable, there is little doubt that an impressive reduction in maternal mortality did occur in Beijing. This has been attributed to training in aseptic deliveries, identified as the most important factor, and also to the organisation of a maternal and child health network, the training and equipping of traditional birth attendants, the education of women of childbearing age, a tripling of the number of obstetric beds and the recruitment and training of triple the number of midwives and obstetricians Citation[1]. A decline in fertility and rising abortion rates due to the one-child policy were also contributing factors, though the decline in fertility in China may be overestimated because of the extent of unregistered births of girls Citation[2].

Health statistics for the country as a whole for the first decades of the People’s Republic are patchy, incomplete and probably unreliable. However, maternal mortality in the rural areas of China was not reduced as substantially as in Beijing Citation[1]. China experienced exceptional economic growth during the Deng Xiaoping or post-Maoist era (from 1978), the same year as the Alma Ata declaration; net per capita household income in the country increased nearly fivefold from 1978 to 1998 Citation[3]. Health is strongly related to income levels. Although it would be reasonable to expect a reduction in maternal mortality in this period, reliable signs are not to be found. According to Chinese health statistics the average maternal mortality ratio in the period 1988–92 was 77 per 100,000 live births Citation[4]. An in-depth (ongoing) study in 300 townships in 1998 found a somewhat higher figure of 115 per 100,000 live births Citation[5]. The results are not comparable due to differences in methodology, but the latter figure is likely to be more reliable.

Maternal health policy in transition

At the time of the Alma Ata Conference, a global consensus on the strategy to advance maternal health in developing countries appeared to have been reached. However, even in the early 1980s the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) disagreed on whether to follow a more comprehensive or a more targeted, vertical approach Citation[6].

During the 1980s the global political climate changed and structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) in many developing countries severely affected basic public services such as education, health and social care, including maternal and child health services. The cutbacks in public budgets necessitated a search for alternative financing. World Bank policy supported a shift from public to private health financing in the 1980s, through privatisation of services, user fees and private health insurance Citation[7].

In 1987 UNICEF published Adjustment with a Human Face, which critically reviewed the experiences of SAPs to that point Citation[8]. The study concluded that growth-oriented adjustment would not be sufficient to ensure protection of vulnerable groups in the short or medium term, but that these groups could be protected by targeted programmes, even in the absence of growth. The report advocated improving the efficiency and equity of social services by moving away from high-cost services to low-cost, basic services.

In 1987, the Safe Motherhood Initiative was launched with the aim of reducing maternal mortality globally by 50% by the year 2000. The initiative covered family planning, antenatal services, delivery care and other pregnancy-related services.

From the late 1980s, the policy role of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the health sector appears to have been challenged, if not taken over, by the World Bank, reducing the role of WHO to one among many suppliers of intellectual inputs Citation[9]. The World Bank added weight to the vertical strategy of targeted interventions, based on cost-utility analyses in the World Development Report 1993; Investing in Health Citation[10]. The Report listed antenatal and delivery care as among the most cost-effective health interventions and recommended they should be included in the “minimum essential package” of clinical services. It was estimated that improvements in antenatal and delivery care could reduce the total disease burden in low income countries by 4%. But these recommendations came in the form of integrated “packages of interventions”, unlike the totally vertical interventions promoted earlier by UNICEF.

Regrettably, the Safe Motherhood Initiative has failed to date in settings where levels of maternal mortality are particularly high. Global maternal mortality has not fallen anywhere near the target set. Instead, at the end of the 1990s, there were more than 585,000 deaths annually and a lack of conclusive progress in many countries, including the poorest. In addition, at least 7 million women annually suffer serious health problems due to complications of pregnancy, abortion and delivery Citation[5].

The two main causes of the failure to reduce maternal deaths identified in 1997 and 1999 were inadequate political commitment and resources, and the fact that priorities were not always clearly defined and interventions not always the most effective Citation[11]Citation[12]. Notably, however, the effects of health sector reforms and the impact of privatisation of health insurance and user fee financing were not explicitly identified as contributing causes of the failure.

China’s health sector reforms: key features

The Chinese health system has been praised for its efficient and accessible network of basic health services, giving priority to prevention. The achievements in health protection have been impressive, especially considering the relatively low level of economic development. Mass organisations and social mobilisation have been prominent features of the Chinese system Citation[13].

The Co-operative Medical System (CMS), a rural public health insurance system, was one of the cornerstones of the Maoist strategy to make basic health services accessible to the rural population in the early years of the People’s Republic. During the post-Maoist era however, the collective economy in the rural areas was transformed into a market system, with the family as the key production unit. Starting from the mid-1980s, health sector reforms (Yiliao Gaige) were launched with cost recovery as a key component. Simultaneously, the coverage of the CMS shrank from 95% of villages at the end of the 1970s to less than 8% just ten years later Citation[14].

The Chinese health sector reforms included both supply-and demand-side reforms, which were necessitated following cutbacks in public funding for health care in 1980–85. A national survey of health services, carried out by the Ministry of Health in 1993, showed that the total county government budget share of hospital funding in China had decreased by 50% in the six years from 1986 to 1992. In urban areas the county government share decreased from 17.8% to only 7.7% and in rural areas from 19.6% to 10.3% Citation[15]. In the same period, the total health sector expenditure increased by 60% in nominal value.

The health sector in China has increasingly been decentralised, with central level influence shrinking at the same pace as the share of public financing has diminished. The system operates in an increasingly diversified manner, and the organisation and quality of services varies from county to county. Thus, the health sector reforms also have local characteristics. A common feature across the country, however, has been increased reliance on cost recovery. On the supply side, the decreasing levels of public funding compelled the decentralisation of management responsibilities, followed by bonus systems for the staff, increases in fee-for-service revenue and revisions of medical pricing. On the demand side, the economic reforms led to the disintegration of the CMS and to extreme levels of out-of-pocket financing. The central control of medical pricing is the key remaining instrument to control supplier-induced demand. The majority of rural Chinese now completely lack health insurance coverage and pay out-of-pocket for all expenditures, including in the case of catastrophic events. Public budgets contribute only a small share of the financing of rural health care and an even lower share for maternal health care, only 25% of the share for curative care Citation[14].

In a previous report, we showed that the impact of health sector reform at macro level has been visible in escalating health care expenditures and a shift to a mix of fewer MCH and other preventative services and more curative and higher level care. A comparison of health care expenditure trend data between an insurance-based county and a county with out-of-pocket financing of health services indicated that out-of-pocket financing constituted a barrier to care Citation[14]. The combination of fee-for-service revenue and profit-related bonus payments for the doctors are a likely cause of this development. Interviews with providers confirmed that supplier-induced demand drives the health system in China towards fewer preventative and more curative services and increasingly more sophisticated care. A majority of clinical doctors (57%) said that it was likely or very likely that the bonus systems commonly in use in Chinese hospitals also encourage overuse of expensive drugs Citation[16].

One of the six counties in the study, Jintan, in Jiangsu province, has developed a relatively comprehensive health financing system, based on the CMS, in order to overcome some of the problems thrown up by the reforms, and has been held up by the Chinese Ministry of Health as a possible national model Citation[14].

The study

In 1995 we carried out a study to identify variables associated with utilisation of maternal health services. We studied trends and identified nine socio-economic variables associated with maternal health care utilisation. We were particularly interested in cost recovery, which is linked to the Chinese health sector reforms.

The study was conducted in six counties with a total population of 3,360,000, in three provinces (Jiangsu, Anhui and Jiangxi) in the Yangtse River valley of Central China, home region of half the Chinese population. The analysis is based on data from a cross-sectional and retrospective household survey (n=5,756) and micro-level observations. The survey covered 2,676 pregnancies in total, with more detailed questions on the most recent delivery (1,222).

The households were selected by multi-stage sampling. Three provinces were selected on the basis of having different rural health insurance systems, representing high, medium and low levels of GNP per capita, and with differences in infant mortality rates (IMRs). The IMRs in Jiangsu were low, in Anhui medium and in Jiangxi high Citation[17].

Because of financial and time constraints, provinces within a reasonable travelling distance from Shanghai were selected. Within each of the three provinces, two counties with similar socio-economic characteristics and different health financing systems (insurance vs. out-of-pocket) were purposely selected. The selection of the provinces and counties was contingent on the willingness of provincial and local health authorities to participate. All the counties that were approached, however, agreed to participate.

All the townships in the selected counties were listed and divided into two groups, according to income levels. Counties with a CMS were divided into four groups of townships, and from these, four townships and one town were randomly selected. All villages in the selected townships were listed and five from each township were randomly selected. Finally, all households in the selected towns and villages were listed from police registers and enumerated. Fifty households in each of the towns and ten in each village were randomly selected.

The household survey was conducted in August and September 1995. The questionnaire used was developed through a consultative process involving Karolinska Institutet in Sweden and Shanghai Medical University, and was field tested in different locations in China. Questions were asked about educational status, occupation, family income, health insurance, distance to health facilities, health, disease history and health care expenditure (out-patient in last two weeks and in-patient in last twelve months) for all household members. Women aged 15 to 49 years were asked about their pregnancy and delivery histories, and antenatal, delivery and postnatal service utilisation. If the members of a household were absent, the interviewers returned up to three times. If they were still absent, the household was substituted by the first neighbour on the left.

There were two quality controllers in each county, of which at least one was from Shanghai Medical University. They went back to two or three households in each township (5% of the sample) to re-interview, comparing the responses item by item and checking that they were recorded accurately. If there were errors, the questionnaire was sent back for re-interviewing. In March 1996 a Chinese-speaking Swedish research assistant re-interviewed 25 households, 10% of the sample in one county for quality control.

Antenatal, delivery and postnatal service utilisation and two negative pregnancy outcomes (miscarriage or stillbirth) were analysed by chi-square and logistic regression analysis.

Socio-economic characteristics

The key socio-economic characteristics of the participating counties are shown in . The lowest GNP per capita was found in Duchang (RMB 1,177) and Yugan (RMB 1278), both in Jiangxi province. The highest was in Jintan (RMB 6,313) and Jurong (RMB 5,272), both in Jiangsu. The two Anhui counties ranged from RMB 2,001 in Fanchang to RMB 2,897 in Tongling.

Table 1 Demographic and socio-economic data, six survey counties, China, 1994

In Jintan more than 90% of the household members were covered by health insurance, leaving less than one in ten to pay out of pocket for health care, while in the other five counties health insurance coverage was only 10–22%.

Educational levels ranged from the highest ratio of senior middle school and higher schooling in Jintan (17.9%) and Duchang (13%) and the lowest in Fanchang (5.9%) and Tongling (6.1%).

The average distance to (public) health facilities was short, with only small differences between the counties. The average distance to primary care (village health station) varied from half a kilometre or less in Jintan, Jurong and Duchang to 1.1 kms in Fanchang. The average distance to secondary care (township hospital) ranged from 1.8 to 3.2 kms. Duchang had the shortest distance and Tongling the longest. Duchang also had the shortest average distance to tertiary care (county hospital), 13.4 kms, while Fanchang had the longest, 18.9 kms.

The cost of antenatal and delivery services

In many counties in China, women planning a pregnancy may join a local maternal pre-payment scheme, which involves a modest annual prospective payment (e.g. RMB 37 in Jintan in 1992) and entitles a pregnant woman to a number of free antenatal and postnatal visits. Health instruction is included, but not the cost of delivery services, drugs, laboratory tests or any treatment fees. The scheme also includes a life insurance element; if the woman dies, a certain amount is paid to her family (RMB 2,000 in Jintan in 1992).

However, the maternal pre-payment scheme had a very low participation rate in five of the six counties: nil in Fanchang, 1.7% of eligible women in Duchang, 3.6% in Tongling, 4.9% in Yugan and 14.9% in Jurong. Jintan, in contrast, had a participation of 43.3%. The cost of participation, RMB 40–60, represented approximately 1% of GNP per capita in the two Jiangsu counties and 2–5% in the other four counties.

The Government health insurance (Gongfei) and the labour health insurance (Laobao) pay for all medical care, including obstetric services, for women who are formal sector employees, up to a ceiling. Women who are married to formal sector employees are reimbursed for 50% of the costs Citation[18]. The CMS similarly covers the cost of medical and obstetric services. Gongfei is tax-financed with co-payments, Laobao is enterprise-financed with co-payments and the CMS is a co-operative prospective plan with co-payments. “Health insurance” in the analysis refers to these three systems. The share of women covered by any form of health insurance (excluding maternal pre-payment schemes) ranged from 90% in Jintan to as low as some 20% in Jurong and around 10% in the other four counties.

The average cost of a delivery in the six counties in 1994, including both normal deliveries and caesarean sections, ranged from RMB 380 to RMB 700, with a mean of RMB 493. The mean annual per capita income in 1994 was RMB 1632 (range RMB 1379–3081), implying that the mean delivery fee was about 30% of the mean annual per capita income, or nearly 10% of the average annual household income, a very high amount to expect families to pay out at one time, along with other associated costs.

Negative pregnancy outcomes: miscarriage and stillbirth

The women of reproductive age were asked about their delivery histories, with follow-up questions on the last pregnancy. The proportion of negative pregnancy outcomes – miscarriages and stillbirths – significantly increased in the 1990s after health sector reforms were introduced in 1985–89 (

Fig. 1 Trends in skilled attendance at birth and negative pregnancy outcomes (miscarriage of stillbirth)

Table 2 Adverse pregnancy outcomes (miscarriage or stillbirth) per 1000 pregnancies, pre-1975–1995, Chi-square test, all pregnancies (n=2676)

When we examined the association between out-of-pocket payments and adverse pregnancy outcomes, we found that the odds ratio for women paying out-of-pocket in the period 1985–89 was 1.54 compared to those covered by some form of health insurance. The odds ratio increased dramatically to 4.54 in the period 1990–95 (P<0.01, Chi-square test) (

Table 3 Trends in delivery outcomes per 1000 live births, pre-1975–1995, Chi-square test, all pregnancies (n=2676), Chi-square (109.21, 12 df)![]()

Trends in maternal health care utilisation

Trends in use of antenatal, delivery and postnatal services in the six counties, from the period before 1975 up to 1995, are presented in . Antenatal service utilisation improved in the 1980s and continued to improve in the 1990s, in line with official policy, while utilisation of other, more vital services dropped significantly from 1990–95.

Table 4 Trends in utilisation of maternal health services, most recent pregnancy, pre-1975–1995 (n=1222)

The proportion of out-of-hospital deliveries decreased after 1975, but rose again in 1990–95 (P-value<0.001, Chi-square test). The proportion of unattended deliveries or deliveries attended only by unskilled staff had fallen to 26% in 1985–89, but rose again in 1990–95, when cost recovery was being promoted (P-value<0.0001, Chi-square test).

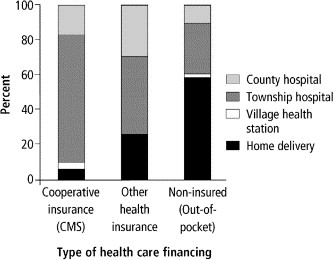

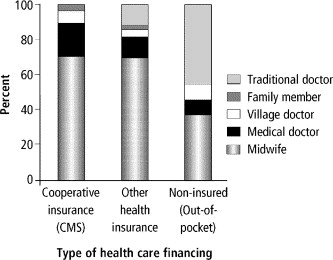

The majority of non-insured women delivered out-of-hospital, while more than 90% of those covered by CMS and more than 75% of those covered by another form of health insurance delivered in a township or county hospital (most recent delivery, ). Less than half of the non-insured women had their deliveries supervised by a doctor or midwife, while more than 90% of those covered by CMS and 85% of those covered by another form of health insurance had access to qualified supervision of delivery (most recent delivery, ).

Utilisation of antenatal services

Significant differences (Chi-square, P<0.0001) were found between the provinces in antenatal service utilisation. Jiangsu, which had the highest participation in maternal pre-payment schemes logically had the highest utilisation rate, 83%, of which 92% of women made three or more visits. Jiangxi had the lowest coverage of maternal pre-payment schemes and also the lowest utilisation, 38%, of which only 37% made the prescribed three or more visits.

In Jiangsu more than 86% of the antenatal check-ups took place at secondary level (township hospital), while in Anhui this figure was 64% and in Jiangxi 37%. In Jiangxi 44% of antenatal check-ups were carried out at tertiary level, compared to 20% of visits in Anhui and 10% in Jiangsu. The fact that in Jiangsu, which has the highest per capita income, the antenatal check-ups took place at township hospitals and not at county hospitals, was probably due to the high participation in the maternal pre-payment scheme, which requires ante-natal check-ups to be done at a township hospital.

Table 5 Antenatal service utilisation in relation to socio-economic variables, deliveries in 1990–95, utilisation in percent of category, Chi-square p-value

The distance to the nearest health facility had a predictable influence on utilisation, but more so for secondary-level than tertiary-level care. Where the distance was less than 5 kms, more than half of the women (54%) went to the county hospital. With a distance of 20 kms or more, less than 2% of women went to the county hospital (Chi-square, P<0.0001). Parity was also significantly associated with utilisation (Chi-square, P<0.0001), decreasing with higher parity.

These differences are often found in data on maternity service utilisation in comparable poor developing country settings. However, differences were also found in coverage by employment position, which in turn was related to health insurance status. Women in government employment had the highest average antenatal utilisation rate (85%), followed by other formal employees (79%), with women farmers significantly lower (57%, Chi-square, P<0.05). Government employees had a higher proportion of three or more visits (100%), than other formal sector employees (92%), with farmers significantly lower (58%, Chi-square, P<0.001).

Means of payment for antenatal services was an important determinant of antenatal service utilisation. Utilisation was significantly higher for government (Gongfei) and labour health insurance (Laobao) participants (85%), followed by CMS participants (83%) and lowest for the non-insured (55%) (Chi-square, P<0.001). Gongfei and Laobao participants had a significantly higher proportion of three or more antenatal visits (80%), CMS participants slightly lower (71%) and non-insured much lower (31%) (Chi-square, P<0.001). Participation in a maternal pre-payment system was a strong indicator of service utilisation (Chi-square, P<0.0001). Participation in a maternal pre-payment system was associated with 90% of the check-ups at secondary level (Chi-square, P<0.01), obviously related to coverage regulations.

Utilisation of delivery and postnatal services

There was significant variation between the six counties in the utilisation of skilled delivery attendance and hospital deliveries (Chi-square, P<0.0001), which was expected, as the insurance cover differs. In Jiangsu province, 95% of the deliveries took place in a hospital, while this figure was 34% in Anhui and 32% in Jiangxi. All the deliveries in Jiangsu were supervised by skilled attendants, contrasting with only 41% in Jiangxi and 38% in Anhui, reflecting the lower levels of insurance coverage.

Almost two-thirds (66%) of the women in Jiangsu, but only one-third (33%) of the women in Anhui had a postnatal check-up within 42 days of delivery.

Utilisation of delivery services was associated with urban vs. rural residence, level of education and occupation (

Table 6 Delivery service utilisation in relation to socio-economic variables, deliveries in 1990–1995, utilisation in percent of category, Chi-square p-value

Delivery service utilisation showed a strong correlation with means of payment. Women covered by government, labour or cooperative health insurance had a significantly higher proportion of hospital deliveries (Chi-square, P<0.0001), skilled attendance at delivery (Chi-square, P<0.0001) and postnatal check-ups. Participation in maternal pre-payment systems was also a strong indicator of service utilisation (Chi-square, P<0.0001).

Service utilisation was correlated with per capita income, increasing with higher income. Only 18% of the women with an annual income of less than RMB 800 had their most recent delivery in hospital and only 21% had skilled attendance at delivery. In contrast, 78% of women with an annual income of RMB 2500 or more delivered in hospital and 81% had skilled attendance at delivery.

Shorter distance to the nearest health facility was associated with greater utilisation of secondary-level care, but not tertiary-level. With a distance to the nearest township hospital (secondary-level) of less than 1 km, more than 85% of the women delivered in hospital and 89% had skilled attendance. With a distance of 3 kms or more, only 37% delivered in hospital and only 23% had qualified supervision. Finally, utilisation decreased significantly with higher parity (Chi-square, P<0.0001).

Nine independent socio-economic variables were tested for covariance using stepwise logistic regression to eliminate confounding: urban/rural residence, education, occupation, health insurance coverage, maternal pre-payment system, distance to secondary-level care, per capita income, amount of savings in the bank and parity. All except per capita income (five classes) and parity (1, 2, 3 or more births) were entered as dummy variables. The P-value was 0.05 for entering the model and 0.10 for removal.

The results (

Table 7 Utilisation of maternal health services and association with socio-economic variables, summary of stepwise logistic regression, deliveries in 1990–95, odds ratio 95% confidence intervals (P-value)

Discussion

As a result of the agricultural reforms starting from 1979 in China, the co-operative financing of rural health services through the CMS disintegrated. Cost recovery became the key element in the health sector reforms of 1985–89, characterised by a shift from public financing of health services to fee-for-service financing, combined with the introduction of profit incentives for providers and reform of the medical pricing system Citation[14].

Our household survey in the six counties shows that maternity service utilisation was significantly affected by method of payment. There also appears to have been a dramatic increase in two adverse outcomes of pregnancy, miscarriages and stillbirths, in the first half of the 1990s. The pregnancy histories reported in our survey go back many years in time, even several decades. For such long recall periods, there is an obvious risk of recall bias. Further research is needed to determine to what extent these negative outcomes truly have a cause-and-effect relationship with the change in service utilisation. The findings, however, are indeed a cause for concern.

Our data show that antenatal service utilisation continued to improve in 1990–95, but only in relation to the number of visits, which were pre-paid if the woman was participating in a maternal pre-payment scheme or covered by another health insurance scheme. We also found significant differences in the utilisation of skilled attendance at delivery and hospital delivery, and crucially, also in adverse outcomes between the population paying out of pocket and those covered by some form of insurance. The odds ratio indicated a 4.5 times higher risk of adverse outcomes for women paying out-of-pocket in 1990–95. Multivariate analysis and logistic regression analysis confirmed a strong association between utilisation of vital delivery services and financing variables of amount of savings in the bank, maternal pre-payment systems and health insurance.

The drop in maternal health service utilisation was subsequent to the propagation of cost recovery in the Chinese health system, particularly affecting the substantial population of women not covered by affordable health insurance schemes. The majority of rural women in particular have no health insurance. Some participate in maternal pre-payment schemes, but the pre-payment schemes do not cover high-cost events, either normal delivery fees or any complications that may occur. The cost of any necessary treatment or drugs would also not have been covered by the maternal pre-payment scheme.

The association between these variables has not yet been studied in many countries. However, an analysis of the socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilisation in Turkey, based on the 1993 Turkey Demographic and Health Survey, also identified an association between health insurance coverage and utilisation of maternal health services Citation[19]. Given that the differences between the Chinese and Turkish health systems are considerable, the possibility of such an association in other countries is suggested.

Over the period under study, fertility patterns in China altered considerably and this is likely to have had an influence on use of maternity services. In general, as fertility declines, families tend to invest more resources in ensuring care for each child, which is likely to be true in the context of one-child families. This makes the decreased use of maternity services all the more striking. It should be noted, however, that women having more than one child in a society with a policy of one-child families may face additional barriers to health care use apart from financial ones.

This study confirms the critical importance of out-of-pocket, fee-for-service payments for health care as a barrier to the use of essential maternal health care. This is not surprising in our study location, bearing in mind that the average cost of a normal delivery in 1994 was 30% of the mean per capita income, or nearly 10% of the average annual household income.

As discussed earlier, aseptic delivery in hospital and skilled birth attendants have been identified as the most important factors in reducing maternal mortality. Although reliable data are scarce, the ongoing, in-depth study quoted at the beginning of this paper Citation[5] shows continuing falls in maternal mortality in China during the 1990s. However, these are national data and could well hide stagnation in certain areas.

The joint WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank Statement on Reduction of Maternal Mortality 1999 stresses the importance of governments providing access to good reproductive health care. The Statement notes that in up to 40% of all pregnancies women are likely to need some form of specific care Citation[12]; this goal was not near to being achieved in these six counties.

Evans has argued that cuts in spending on public education resulting from structural adjustment programmes would eventually impact on maternal health, by reducing educational levels among women. Evans further suggested that user fees charged for normal deliveries and caesarean sections would drive more women to have unattended deliveries and into the hands of quacks, with a resulting higher maternal mortality Citation[20]. Our study has clearly shown that the rate of home deliveries without a skilled attendant increased in Central China following the Chinese health sector reforms. It has also shown that equity in access to maternity services, i.e. that equal access is assured for equal needs, has not been achieved under the Chinese reforms, e.g. in the uptake of the maternal pre-payment scheme or other health insurance schemes covering maternity care.

Our results suggest an association between utilisation of maternal health services and a positive impact on delivery outcomes. They also suggest that health insurance coverage, independent of income, may contribute to higher utilisation of hospital delivery and qualified birth attendants.

Jintan county has achieved a near total health insurance coverage for its citizens. It is also the wealthiest of the six study counties. The proportion of population covered by health insurance appears to increase with higher average income level, which indicates a need for cross-subsidisation of poorer counties.

In conclusion, we would argue that maternal pre-payment and health insurance schemes would better contribute to increased utilisation of antenatal and postnatal services as well as hospital delivery and skilled attendants at delivery in settings such as central China if all these service components were covered and schemes were available and affordable to even the poorest Chinese women.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported financially by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Department for Research Co-operation with Developing Countries (SIDA/SAREC). The helpful comments by the reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- R.Y Yan. Maternal mortality in China. World Health Forum. 10: 1989; 327–331.

- L Bogg. Family planning in China: out of control. American Journal of Public Health. 88(4): 1998; 649–651.

- China Statistical Yearbook 1999. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1999

- Selected Edition on Health Statistics of China 1991–95. Beijing: Ministry of Health, People’s Republic of China, 1996 [In Chinese]

- The State of the World’s Population 1999, New York: UN Population Fund, 2000

- A Lafond. Spotlight on international organizations: UNICEF. Health Policy and Planning. 9(3): 1994; 343–346.

- Financing Health Services in Developing Countries: An Agenda for Reform. A World Bank Policy Study. Washington DC: World Bank, 1987

- G.A Cornia, R Jolly, F Stewart. Adjustment with a Human Face: A UNICEF Study. 1987; Oxford University Press for World Bank: New York.

- K Buse. Spotlight on international organizations: the World Bank. Health Policy and Planning. 9(1): 1994; 95–99.

- World Bank. World Development Report 1993 – Investing in Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993

- Safe Motherhood: Evaluation Findings. Issue 10. New York: Office of Oversight and Evaluation, UN Population Fund, January 1999

- Reduction of Maternal Mortality; A Joint WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF World Bank Statement. Geneva: WHO, 1999

- W Hsiao. The Chinese health care system: lessons for other nations. Social Science & Medicine. 41(8): 1995; 1047–1055.

- L Bogg, H.J Dong, K.L Wang. The cost of coverage: rural health insurance in China. Health Policy and Planning. 11(3): 1996; 238–252.

- Research on National Health Services: An Analysis Report of the National Health Services Survey in 1993. Beijing: Ministry of Health, People’s Republic of China, November 1994

- H.J Dong, L Bogg, C Rehnberg. Health financing policies; providers’ opinions and prescribing behaviour in rural China. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 15(4): 1999; 686–698.

- China Statistical Yearbook 1993. Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1993

- A Ron, B Abel-Smith, G Tamburi. Health Insurance in Developing Countries: The Social Security Approach. 1990; ILO: Geneva.

- Y Celik, D.R Hotchkiss. The socio-economic determinants of maternal health care utilization in Turkey. Social Science & Medicine. 50(2000): 2000; 1797–1806.

- I Evans. SAPping maternal health. Lancet. 346(21Oct): 1995; 1046.