Abstract

This paper examines the role of oversight in influencing the health sector, using examples from sexual and reproductive health services in India. Rather than simply trying to provide services through traditional bureaucratic mechanisms, governments can make use of oversight tools to influence how health care is delivered through the public and private sectors. Three main oversight functions are described: understanding health system performance, deciding when to intervene in the health system and strategizing and implementing change. Governments also need to understand the ethical basis for decisions. The potential for administering oversight through policymaking, disclosing and informing, regulating, collaborating, and strategically subsidising and contracting services in sexual and reproductive health is described. This approach implies an engagement with a broader set of stakeholders in the health sector than is often the case. It requires a set of skills for public officials beyond managing public programmes, and relies on a larger role for other stakeholders and the general public. When applied to reproductive and sexual health, implementation of the full range of oversight functions offers new opportunities to provide more effective, equitable, accountable and affordable services.

Resumen

Este artı́culo examina la influencia de la vigilancia sobre el sector salud, utilizando ejemplos tomados de los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva en la India. En lugar de simplemente pretender proveer servicios mediante los mecanismos burocráticos tradicionales, los gobiernos pueden utilizar las herramientas de la vigilancia para incidir en la provisión de los servicios de salud en los sectores públicos y privados. Se describen tres funciones fundamentales de la vigilancia: comprender el desempeño del sistema de salud, decidir cuándo intervenir en el sistema de salud, y diseñar estrategias e implementar cambios. Los gobiernos deben además comprender las bases éticas de la toma de decisiones. Se describe la capacidad potencial de gestionar la vigilancia mediante la elaboración de polı́ticas, la divulgación e información, la regulación, la colaboración, y el subsidio y contratación estratégica de servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva. Este enfoque implica tratar con un conjunto amplio de partes interesadas en el sector salud. Requiere que los funcionarios públicos adquieran capacidades que les permita ir más allá de la administración de los programas públicos, y que otras partes interesadas, y el público en general, tengan un papel mayor. Cuando se aplica a la salud sexual y reproductiva, la implementación de una gama completa de funciones de vigilancia ofrece nuevas oportunidades para proveer servicios más eficaces, equitativas, responsables y alcanzables.

Résumé

Cet article examine l’influence du contrôle sur le secteur de la santé, et l’illustre avec des exemples des services de santé génésique en Inde. Au lieu d’essayer simplement de fournir des services par les mécanismes bureaucratiques traditionnels, les autorités peuvent utiliser les outils de contrôle pour influencer la prestation des soins de santé dans les secteurs public et privé. Trois principales fonctions de contrôle sont décrites: comprendre les performances du système sanitaire, décider quand intervenir dans le système sanitaire, définir des stratégies et appliquer les changements. Les autorités doivent aussi comprendre les bases éthiques des décisions. L’auteur décrit le potentiel de gestion des services de contrôle par la définition des politiques, l’information, la réglementation, la collaboration et les subventions stratégiques et l’établissement de contrats pour les services de santé génésique. Cette approche suppose de s’engager avec un ensemble plus large d’acteurs du secteur de la santé que ce n’est souvent le cas. Elle demande aux fonctionnaires un ensemble de compétences allant au-delàde la gestion des programmes publics, et est fondée sur un rôle plus vaste pour d’autres parties intéressées et pour le public. Quand elle s’applique à la santé génésique, la mise en œuvre de tout l’éventail des fonctions de contrôle offre de nouvelles possibilités de fournir des services plus efficaces, équitables, responsables et abordables.

The current epidemic of health sector reforms around the world has prompted a renewed look at how such changes are arranged. Questions are increasingly raised about how reforms are conceived and conducted, and what effect they have on health programmes and people’s health. In addition to concerns about who gains or loses from health sector reforms Citation[1]Citation[2]Citation[3]Citation[4], those involved with sexual and reproductive health or other specific health programmes need to know how reforms affect their areas of interest Citation[4]Citation[5]. In this paper, I argue that addressing these questions is central to the role of oversight in the health sector. In comparison to the provision of health services and their financing, oversight roles are often neglected in the analysis of health systems. Using examples largely from India, the paper examines how oversight functions can be used to influence sexual and reproductive health services in low-income countries.

In this paper, I use “oversight” to mean an active watching over of the health sector, actions that are based in ethics and economics. Underlying all policy decisions or articulation of a vision for the health sector is a set of implicit or explicit values. These values may be translated into a legal framework or expressed through ideologies. A narrow view of oversight deals with the set of laws, regulations, and orders that provide a legal framework for health sector activities. This article examines a broader set of oversight functions that shape the health sector. In the case of some command economies (i.e. countries where there is strong public control over economic resources and production for state or collective interests) and post-colonial settings, government oversight efforts have been aimed at rigidly controlling activities in the health sector Citation[1]. In other countries, oversight has been used more indirectly. The World Health Report 2000 proposes a stewardship model for the health sector, wherein the state acts as an agent responsible for the welfare of its population Citation[6]. Saltman and Ferroussier-Davis, who trace the stewardship concept from its religious roots to its ecological and sociological uses, note that this approach has placed a consistent emphasis on trust, legitimacy, and the pursuit of a common good Citation[7]. In this paper, I am less concerned with the particular style of intervention than with the opportunities for improving the health system that are created through various oversight functions. Whatever the approach taken, oversight should not imply neglect or a failure to fulfil these functions.

Public oversight in the health sector has been a concern of governments throughout history. The earliest documentation of regulation in the practice of medicine dates back to the Code of Hammurabi (c.1750 BCE), wherein eight of the 282 provisions are devoted to regulating medical fees, and two to punishing doctors when their treatments cause harm Citation[8]. With the development of modern states in the 19th and 20th centuries, many governments developed laws to protect the health of their citizens, social insurance to finance health care and public health systems to provide services Citation[9]. In the modern Indian state, the foundations for a public role in the health sector were described at the time of Independence, in the Bhore Report Citation[10], the Indian Constitution and the five-year national development plans. As was the case for many other former colonies and countries emerging from war, India envisioned heavy state involvement in the provision of health services to all. The private health sector, which at the time of Independence consisted of a few missionary hospitals and a large number of practitioners of Indian systems of medicine, was largely ignored. As a result, government created an extensive network of public rural health facilities to provide curative care and maternity and child health services, and little attention was paid to the role of the private sector and how it would be directed or influenced through oversight.

The traditional framework for oversight in most low-income countries involves a number of common elements: international treaties and conventions; national constitutions and founding acts of public agencies; criminal law; civil law; and contract law. Whereas these legal tools usually exist on paper in most developing countries, their application is often erratic. India, for example, has a comprehensive set of legal instruments for the health sector, including a Constitution that identifies equitable access to health care as a directive principle of the state, though not explicitly a fundamental right of its citizens Citation[11]. In part because of the inability of India’s legal system to deal with an enormous burden of litigation, a new set of consumer laws has helped to establish a parallel set of courts to deal with public complaints over goods and services, including the practice of medicine. Recent studies have shown that the consumer laws may have potential to improve health care Citation[12], but in practice the cases involving medical complaints have been infrequent, time-consuming and biased towards wealthier and literate complainants Citation[13].

Unfortunately, there are many examples in India of well-intentioned laws that have not provided sufficient oversight in the health sector. The list of inadequacies and abuses include laws against sex determination tests that have done little to stem the tide of abortions of female fetuses Citation[11], an abortion law of 30 years ago that legalized the procedure but did far too little to reduce the level of unsafe abortions Citation[14], misuse of the Mental Health Act to incarcerate sane women in asylums because of dowry disputes or marital conflict Citation[15], and unethical clinical trials of contraceptives Citation[15]. Rather than focusing on the traditional legal and regulatory channels, this article examines alternative ways for governments, health professionals, and concerned civic-minded organizations and citizens to provide leadership through oversight of the health sector. The main oversight functions can be categorized into three areas:

| • | understanding health system performance | ||||

| • | deciding when and how to intervene in the health system | ||||

| • | strategizing and implementing change | ||||

Understanding health system performance

If governments, professional associations, or other interested parties are to provide leadership in overseeing the health sector, they need to understand the nature of the health system, how to measure its performance, and how to identify the underlying problems and solutions. An understanding of the health sector involves recognizing the key stakeholders (from government, to the private sector and the public itself), the main functions, the outcomes of the system, and the underlying ethical values of policy decisions.

When a health sector is undergoing reforms, ethical values may be in conflict with each other. For example, a government may want to promote equity and justice (e.g. by providing fair access to reproductive health services) but it may also be limited by the need to promote economic efficiency (e.g. by containing costs and aggregate public spending on health). India’s National Population Policy has promoted a plan to provide equal access to reproductive and child health services Citation[16], though government has more recently acknowledged that the public sector has not provided sufficient resources for health Citation[17]. Government is encouraging freedom of choice by allowing people to freely choose providers (and more recently health insurers), and by allowing providers to retain considerable autonomy over their practices, at least in the private sector. However, these choices may need to be limited because of equity and efficiency considerations, or by the desire to promote social cohesion through a strong public health service or social health insurance scheme.

Clarifying the ethical foundations of decisions in the health sector is an oversight activity that can help to differentiate positions that people hold, as well as to provide support for day-to-day decision-making. Identifying and making explicit the values that underlie policy decisions may be an important factor in either changing policy or mobilizing support. Whether or not the ethical foundations are made explicit, health sector policies and decisions will inevitably reflect values of some key stakeholders.

The performance of a health system, like any other system, can be measured in terms of the outcomes it is expected to produce. There are at least three dimensions of outcomes that provide an indication of the overall performance of the health system:

| • | health status (e.g. measures of population mortality, morbidity, disability, and malnutrition); | ||||

| • | financial status (e.g. indicators of the risk of poverty due to illness or paying for health services); and | ||||

| • | satisfaction (e.g. measures of how satisfied people are with services provided in the health system, or the degree to which their rights and dignity have been protected within the health system) Citation[18]. | ||||

Ethical assumptions also affect the choice of indicators for understanding health system performance. The World Health Organization proposed an indicator of financial fairness based on proportionately equal contributions to health expenditures by different income groups Citation[6]. Wagstaff objected to this measurement because it assumes that a pro-poor distribution of financing is just as unfair as a pro-rich distribution Citation[20]. I am more concerned about the problem of financial risk than the question of fairness in contribution. In other words, it is important that people not fall into poverty or debt as a result of illness or paying for health care. In India, for example, what people paid for health as a proportion of per capita income in 1995–96 was actually progressive (i.e. the rich paid a higher proportion of their income than the poor), yet payment for health care is financially risky Citation[18]. In addition to the problem of accumulating debt, nearly one quarter of all hospitalised Indians were estimated to fall below the poverty line as a result of medical payments that year Citation[18].

In the field of sexual and reproductive health, measurements of outcome indicators have been problematic. Despite the appeal of using maternal mortality ratios (or rates), obtaining such data is expensive and full of error, making it difficult to measure progress over time Citation[21]Citation[22]. A cross-country comparison of maternal mortality ratios demonstrates a wide variation in levels, particularly among low-income countries. There is a trend for poorer countries to have higher levels of maternal mortality, but also there is lower variation among richer countries, where the importance of measuring progress is less urgent (

Fig. 1 International comparison of maternal mortality ratio (1980–99) and per capita GDP (1999) Citation[27]

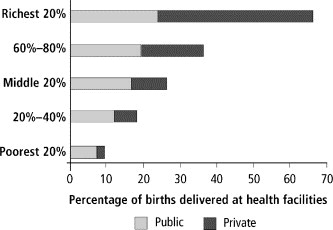

Measures of outcomes of the health system may provide valuable information about its performance, but they are often insufficient for diagnosing the underlying problems of the system or of specific programmes. Measurements of inputs, processes and outputs are needed to assess efficiency, coverage, affordability and equity within the health system. Fortunately, there is an emerging consensus on how to do this in sexual and reproductive health. For example, maternal health programmes and projects can be well monitored through process and output indicators, such as access to essential obstetric care and coverage of skilled attendance at birth Citation[28]Citation[29]. Campbell Citation[26] has argued for better record-keeping and more critical analysis of data to monitor programmes more effectively, while AbouZahr Citation[21] describes a range of useful diagnostic and action-oriented techniques. Despite these advances in measurement and use of data in sexual and reproductive health, there is relatively little attention to the financial risks involved in sexual and reproductive care. The observation that in low-income countries, the rich-to-poor ratios in the rate of attended deliveries is much greater than for immunizations, diarrhoea treatment or pneumonia treatment, suggests that financial risks may play a particularly important role in sexual and reproductive health services Citation[30]. This is evident in India, where a recent analysis of institutional deliveries showed that not only is the overall level quite low (27% in 1995–96), but the differences between pregnant women of different income groups are enormous (

Fig. 2 Percentage of institutional deliveries in the public and private sectors according to income quintile in India, 1995–96 Citation[18]Citation[41]

also raises questions about the roles of the public and private sectors. The private sector is routinely ignored in assessments of health system performance, and is often missing in official statistics Citation[31]Citation[32], despite the major role it plays in delivering health care. In India, the public and private sectors each provide about half of all institutional deliveries. Both sectors tend to favour services to the better off, the private sector even more so. Most births are still occurring at home, however, and without medically trained attendants Citation[19]. In contrast, there are large differences between these figures and figures for inpatient and outpatient curative services, as well as antenatal and other preventive services. For example, about 80 percent of all outpatient treatments in India occur in the private sector, including for patients below the poverty line Citation[18]. Thus, statements about the public-private mix of services and use by the poor need to be specific for the type of health services.

A number of groups have recently analysed issues facing India’s public sector Citation[17]Citation[18]Citation[33] which in large part are applicable to sexual and reproductive health services there and in other low-income countries. Poor governance, rigid management systems and a low level of resources are common features. Budgets are not only small, but rarely do managers have sufficient ability to allocate them as needed. Funds are often not linked to the needs of the community, or to the use of services. Public sector managers often have limited incentives to perform well, are not well trained in management and are not given the authority to make decisions. The climate and culture of the workplace rarely enables workers to take ownership of work responsibilities and organizational goals. Desirable features such as task performance, support to perform work, teamwork and innovation are rarely the major driving forces. Instead, the public sector often emphasizes hierarchy and power. Bureaucratic rules and procedures may dominate behaviour, or political connections, ethnic affiliation or union influence may be more important than individual or group performance. As a result of these problems, the public may have few alternatives to seek better care or to redress problems within the public sector.

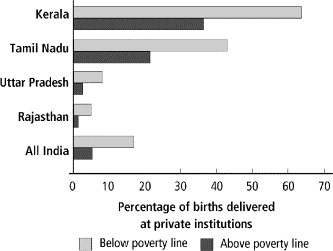

In India, as in other low-income countries, there is a double-edged problem with private sector health service provision. First, there is a missed opportunity to capture the energy of the private sector to pursue public objectives. Second, there is a failure to counteract the market failures of the private sector Citation[18]Citation[34]. These occur in part because private providers are rarely held accountable for the quality of services or for the prices they charge. This results from a lack of institutional quality assurance mechanisms and the absence of large group purchasers who would demand better rates and quality than individual patients Citation[35]. Providers have an incentive to provide services that are not needed, particularly since most are paid on a fee-for-service basis Citation[36]. In India, the consequences can be seen in excessive caesarean section rates Citation[37]Citation[38], unnecessary hysterectomies Citation[39] inappropriate drug treatments Citation[40] and unsafe abortions Citation[14]. Private providers will complain that they face a wide range of business constraints, including arcane and difficult regulations, extortion from public officials, erratic public utilities, limited access to credit, and “unfair” competition from informal or unqualified providers Citation[18]. These factors influence the location, quality and pricing of private services in ways counter to public policy objectives. , for example, shows how institutional deliveries in the private sector are five to ten times more common in the Indian states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu than in Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, where health outcomes are much poorer. The utilization rates for those above the poverty line are two to four times greater than those below the poverty line. Large differences in prices can also be seen across the country: the price per day of hospitalisation in Tamil Nadu is twice as great as it is in Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan Citation[41].

Fig. 3 Percentage of deliveries in private health institutions in four states of India and all-India for those above and below the poverty line, 1995–96 Citation[41]

Deciding when to intervene in the health sector

In India and other low-income countries, where public sector health budgets are too small, inequitably distributed, and focused on urban, curative care but without the institutional capacity to share risks (i.e. through health insurance), and where public service delivery is top-heavy and inefficient, there is a particular need for governments to carefully choose when to intervene. Such decisions are invariably political, and sensitive to the context in which they occur, the policy processes involved and the roles of various stakeholders Citation[42].

Understanding the potential justifications for government involvement in the health sector is a useful tool to influence policy processes, and particularly if the strategy is to convince those who resist greater involvement. In India and many other low-income countries, the fiscal constraints on the public budget often prevent Ministries of Finance or Planning from allocating greater resources to the health sector. Because Finance Ministries represent a key stakeholder in allocating resources and determining the ability of the public sector to intervene in the health sector, it is important to be able to communicate on their terms.

The economic arguments commonly used to justify state intervention in the health sector were summarized recently by Musgrove Citation[43]. This is a utilitarian approach to optimising efficiency and equity that is based on the economic nature of various health services, and the failure of health markets. The criteria can be summarized as follows:

| • | Does the health service benefit only the individual who uses the service, or do others also benefit? | ||||

In economic terms, one justification for government intervention is based on whether the service is a public good or has positive externalities. A private good is one that only benefits the individual who uses it, whereas a pure public good is non-excludable (those who haven’t paid for a service cannot be excluded from benefiting from it), non-rival (use of the service by one person does not reduce its availability to another) and non-rejectable (one cannot choose to forego consumption). Externalities refer to the benefits or harm that affect others, and not just the individual who uses the service. Economists often describe most health services as being mixed public-private goods, with a varying degree of externalities Citation[44]. Oversight activities are primarily public goods, while financing interventions may provide significant externalities if they can be used to reduce poverty or improve quality and efficiency in the health system.

When national and state governments of India develop population policies or implement vector control initiatives, these interventions are seen as largely public goods, and therefore deserving of government intervention. When a non-profit organization prepares an assessment of the Indian health system to inform public debate, as was done by the Voluntary Health Association of India, Citation[45] it too has provided a largely public good. Family planning interventions are considered a mixed public-private good with considerable positive externalities. Since contraceptives consumed by one couple cannot be simultaneously consumed by another, people can choose to reject family planning, and contraceptive products can compete for market share; they are not considered a purely public good. Nonetheless, governments and other civic-minded organizations promote family planning because of the positive externalities for family health, the economy and the environment.

Among health services, public health preventive services tend to offer greater externalities than other health services. Inpatient curative services have the least benefits accruing beyond the individual who receives the services, and are therefore more like private goods. This viewpoint may provide a partial explanation of why Finance Ministries are reluctant to allocate more funds to curative care, which is often considered as a bottomless pit that benefits only private individuals. Of course, politicians often recognize that hospital care is highly visible and valued by the public, which may partly explain why they are able to attract relatively high levels of government funds.

| • | Is the intervention needed to counteract what would happen if the service were left entirely to the private sector? | ||||

| • | Is the intervention needed to reduce poverty or inequities? | ||||

| • | Is the intervention cost-effective? | ||||

Although it is disputed whether cost-effectiveness should be a main criteria for setting public priorities, it is at least clear that any intervention provided from public resources ought to produce a desired effect and be designed to provide the best value for money. This criterion is used most often in helping to define basic or essential packages of care in many countries, including the set of reproductive and child health services provided by the public sector in India. But if cost-effectiveness is defined as the cost compared to a health system outcome, such as the cost per life saved, then it is difficult to assess how oversight and financing interventions would produce the same kind of impact on health as public health or clinical service provision, in part because of a problem in attribution for these interventions. Cost-effectiveness is also highly variable among service delivery functions, with outpatient and public health services generally having greater cost-effectiveness than inpatient care.

Whether based on economic arguments outlined above, political expedience or other criteria such as human rights or social preference, the ability to justify government intervention is an important oversight task. Although largely a government responsibility, non-governmental stakeholders contribute to this oversight function by providing information or directly engaging in public debate on when the public sector should intervene.

Strategizing and implementing change

Strategizing and managing the process of change in health systems are important functions of health reform Citation[48], and are here considered as a part of oversight functions. Strategizing for change may be as important as the technical features of the reform itself, as it may well make the difference between whether a major health reform is implemented or not. As identified in Saltman Citation[49], the main steps include:

| • | Analysing the stakeholders and their interests in reforming the health system. | ||||

This step involves a mapping of interest groups and key individuals likely to promote or resist a change in policy at the national, state, and institutional levels Citation[50]Citation[51]Citation[52]. Their interests may be parochial, but reviewing the underlying ethical implications involved may be helpful. Different groups may be trying to promote equity, fulfil legal responsibilities, guarantee human rights or simply save costs or address technical deficiencies. One example of a stakeholder analysis in India examined the potential of hospital accreditation as a means of improving the quality of health services in Mumbai Citation[53]. As a result of a collaborative approach in charting out the concerns of different interest groups, a fledgling accreditation body was established with the support of major private hospitals and other stakeholders.

| • | Assessing the ease of implementing change and making adjustments. | ||||

This step involves assessing the conditions for facilitating change in the health system. The type of factors that need to be considered include: the number of implementing agencies involved, the clarity of goals, the degree and duration of policy change, the visibility of costs and benefits, and the time frame. Health reforms would need to be adjusted according to the analysis. In India, most reforms in the health sector in the last decade have been slow, incremental and fragmentary Citation[18]. Yet within the Family Welfare Programme, there has been a major shift away from a target approach to increasing contraceptive prevalence Citation[16]. The target approach was adopted in the 1960s as a management tool to pursue a limited set of clear and visible reduction in population growth rates in a specific time Citation[54]. Although contraceptive coverage was increasing, the corresponding fertility rates were not declining as expected, and significant gaps in quality and range of services remained Citation[54]. By 1995, the government was experimenting with a non-targeted approach in one district in each state, in part to respond to the objections from numerous constituencies to the coercive and ineffective nature of the target approach. Today, a target-free approach has become national policy, but problems in service quality persist, along with an increasing divergence in conditions between the Indian states Citation[18]. This leaves the door open for the states to develop their own policy and programme initiatives Citation[16]. Although a number of states have developed their own population policies in the last two years, it remains to be seen whether this will lead to improved performance and a reduction in gaps between the states.

| • | Creating the processes to implement change. | ||||

The main feature of this step is to find ways to mobilize support for change. Roberts et al suggest specific political strategies for implementing reform Citation[48]. All involve identifying networks of supporters for change and managing communications. Mobilizing support may involve seeking consensus, coalition building or finding ways to keep opposition constructive or marginalized. When reforms are highly politicised, reformers may try to undermine opposition. Saltman points out that to gain support within a bureaucracy, one approach is to involve planners and managers in the analysis of how to execute policy Citation[49]. Yet mechanisms for broader consultation and re-planning may also need to be built in. Promoting public awareness and involving people in the planning process are particularly appropriate for populist reforms. The major analogy in India concerns the recent emphasis on strengthening local government bodies and increasing the participation of women and vulnerable groups in local political processes, whose mandate covers the management of primary health services. Despite constitutional amendments in 1993 and considerable investment in local bodies to support these changes, in much of India, the reforms have been very slow.

The main ways to intervene in the health sector involve the delivery and organization of services and their financing, and in oversight. Administration of oversight is especially dependent on government, and includes a wide set of tools, including:

| • | policymaking, | ||||

| • | disclosing and informing, | ||||

| • | regulating and mandating, | ||||

| • | collaborating, and | ||||

| • | strategically subsidizing and contracting services. | ||||

Policymaking is intended to articulate the vision for the health sector, and to provide a framework for actions. As discussed above, policymaking is largely a government function, though considerable inputs are needed from various interest groups for policies to gain acceptance and have a greater chance of success in implementation. Providing information to the public, health providers, and financiers is intended to improve accountability and reduce information asymmetry that causes market failures in the health sector, and to balance the power of different stakeholders Citation[55].

Regulation is commonly used to mean the formal enforcement of laws and rules set by government, though broader definitions are also available Citation[56] and more comprehensive frameworks exist Citation[57]Citation[58]. Mandates are a type of regulation that place a positive requirement to provide a certain service (e.g. a requirement to offer publicly financed tetanus immunizations if maternity services are offered). In high-income countries, regulation usually includes activities such as licensing doctors and hospitals, controlling the quality, distribution, and pricing of drugs, as well as the use of incentives, self-regulation and consumer information. While some low-income countries have adopted these tools, many have adapted an approach of dictating compliance to standards in a rigid and bureaucratic manner. Even though few countries have the capacity to enforce such regulations effectively, this remains a common approach in India and other post-colonial countries Citation[1]. Alternative approaches that do not depend on government enforcement capabilities therefore need to be tried.

Collaborative interventions are one such approach. These are partnerships that include the voluntary association of different types of actors around areas of common interest, and usually include groups outside Ministries of Health. Collaborations may be organized around single issues, as often occurs with research collaborations among different organizations. Collaborations are also established to deal with more complex problems than can be tackled by a single organization and affect multiple interest groups, as is common in the health sector. Recently, a number of collaborative ventures have become prominent at the global level (e.g. Global Alliance on Vaccines and Immunizations, Roll Back Malaria, International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, Onchocerciasis Control Program, Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention) Citation[59] and national level (e.g. sector-wide approaches in health) Citation[60]. Although local level collaborative approaches have been shown to be successful in fragmented health systems such as in the United States Citation[61]Citation[62]Citation[63], their value in low-income countries has not been well documented. Good collaboration can take on many forms and issues, but usually occurs when there is interdependence of partners and joint ownership over decisions and future directions Citation[61].

Subsidizing and contracting could be viewed as financing tools, but since there are also considerable non-financial elements in these arrangements, they are highlighted here as well. Subsidies and contracting often include stipulations about the type of services to be provided, as well as monitoring and reporting requirements. In India, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are contracted by government to provide a set of reproductive and child health services under the supervision of a “mother NGO”, and are required to report on their activities. The effectiveness of this approach has yet to be evaluated comprehensively, though the practice is expanding.

Although this article presents oversight as primarily a government responsibility, public action should not be equated with government action. There are alternative ways in which oversight can be administered for public objectives without direct government intervention. In addition to the traditional model of government enforcement of regulations, there are at least four other approaches:

| • | Engage independent monitors to assess the performance of public and private sector providers. To some degree this happens through the monitoring of reproductive health service utilization and outcomes from the Reproductive and Child Health Surveys and National Family Health Survey, but the identity of individual providers and their performance is not reported in these surveys. | ||||

| • | Support consumer organizations to act as advocates for consumers. For example, the Voluntary Organization in Interest in Consumer Education in India has recently become involved in advocating for the rights of patients, and in testing drugs and medical products sold to consumers. | ||||

| • | Encourage professional self-regulation, as is being done for accreditation of hospitals in Mumbai Citation[53], or for continuing medical education, or patient redress. | ||||

| • | Foster public-private collaboration to build networks of providers, to share information and materials, and jointly develop and use quality standards. Public-private forums have been started in a number of Indian states to develop a common agenda for action in the health sector. | ||||

In most countries, no single approach seems likely to succeed by itself, as each is vulnerable to “capture” by particular stakeholders. Each of these approaches can also make use of the media to facilitate the flow of information, raise public awareness and demand, and add pressure on providers to behave according to publicly acceptable norms.

Discussion

Oversight functions cut across the main ways to intervene in the health sector, including the ways that services are provided, organized and financed. For example, it is an oversight decision whether a government will provide health services to everyone, or just for specific programmes and populations. In India, the practice is that public resources for sexual and reproductive health services are spread thinly across the country, with relatively little concentration of efforts on vulnerable groups, or in areas that are not served by the private sector. It is an oversight function to choose how resources for health are generated, whether and how they should be pooled, and how practitioners should be paid. In India, government has acted to raise revenues through general taxation and allocates only a little for public health, leaving the majority of health financing to private individuals to pay on a fee-for-service basis Citation[18]. As is the case in other countries, sexual and reproductive health services have become more integrated in India since the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo. Although specialized family planning clinics and sterilization camps still exist in India, additional family welfare and sexually transmitted infection services have been added in many cases. Most of the organizational changes in the health sector in India and other low-income countries have occurred within the public sector. Few countries have attempted to define a clear role for the various types of private sector actors, despite their importance in the provision of health services, and an increasing role in medical education Citation[64].

The broad range of interventions available in the health sector highlights the importance of monitoring and reporting the results of these interventions. Good oversight of the health sector would involve monitoring the effects of changes made. Though there is a growing movement to provide evidence-based medicine Citation[65], there is less evidence about what works best in interventions for health financing and organization of health care. Oversight interventions themselves have rarely been a subject for evaluation, particularly in trying to link them to health outcomes. For example, two recent reviews of interventions for oversight of the private sector in low-income countries found many examples of good practice but a very weak evidence base Citation[66]Citation[67]. It is therefore important that oversight interventions be tested in a more rigorous way so that countries can assess what will work best in their own context.

Given the dominance of private sector provision in low-income countries and the scarcity of public resources, governments and civic bodies need to pay more attention to oversight. The oversight interventions described in this paper offer opportunities to assure more effective, equitable, and affordable reproductive and sexual health services. Rather than simply trying to provide services through traditional bureaucratic mechanisms, governments can make use of oversight tools to influence how health care is delivered through both the public and private sectors. This paper argues that to do so effectively, governments need to understand the ethical basis for decisions, how the health sector performs, what types of interventions it can justify within the health system, and how it can implement them. This approach implies an engagement with a broader set of stakeholders in the health sector than is often the case. It also requires a set of skills for public officials beyond managing public programmes, and relies on a larger role for other stakeholders and the general public.

Acknowledgements

Comments on previous drafts of this paper from William Reinke were much appreciated. I also acknowledge the work of colleagues who conducted studies on the Indian health system, including those from the National Council for Applied Economic Research, Voluntary Organisation of Interest in Consumer Education, and staff at the World Bank.

References

- G. Bloom. Equity in health in unequal societies: meeting health needs in contexts of social change. Health Policy. 57(3): 2001; 205–224.

- D.R. Watkins. The need for equity-oriented health sector reforms. International Journal of Epidemiology. 30: 2001; 720–723.

- M. Whitehead, G. Dahlgren, T. Evans. Equity and health sector reforms: can low-income countries escape the medical poverty trap. Lancet. 358(9284): 2001; 833–836.

- H. Standing. Gender and equity in health sector reform programmes: a review. Health Policy and Planning. 12: 1997; 1–18.

- A. Langer, G. Nigenda, J. Catino. Health sector reform and reproductive health in Latin America and the Caribbean: strengthening the links. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(5): 2000; 667–676.

- World Health Organization. World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO, 2000. p. 4

- R.B. Saltman, O. Ferrousier-Davis. The concept of stewardship in health policy. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(6): 2000; 732–739.

- Code of Hammurabi. King LW, translator (1910). In: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School, 1996. Available from: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/medieval/hamframe.htm. Accessed 8 July 2002

- M.I. Roemer. National Health Systems of the World. 1991; Oxford University Press: New York.

- Indian Law Institute. Legal Framework for Health Care in India: Experience & Future Directions. New Delhi: Butterworth Publishing, 2001

- Bhore J, Amesur RA, Banerjee AC. Report of the Health Survey and Development Committee. Vol. I. New Delhi: Government of India, 1946

- R. Bhat. Regulating the private health care sector: the case of the Indian Consumer Protection Act. Health Policy and Planning. 11(3): 1996; 265–279.

- Misra B, Kalra P. A Study on the Regulatory Framework for Consumer Redress in the Healthcare System in India. New Delhi: Voluntary Organisation in Interest of Consumer Education. 2000. Available from: http://wbln0018.worldbank.org/SAR/India/HealthESW/AR/DocLib. nsf/Table%20Of%20Contents%20Web?OpenView & ExpandView. Accessed 8 July 2002

- P. Varkey, P.P. Balakrishna, J.H. Prasad. The reality of unsafe abortion in a rural community in South India. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 83–91.

- Gopalan S, Shiva M, editors. National Profile on Women, Health and Development: Country Profile – India. New Delhi: Voluntary Health Association of India and World Health Organization, 2000

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The National Population Policy 2000. New Delhi: Government of India, 2000

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Health Policy 2002. Available from: http://mohfw.nic.in/np2002.htm. Accessed 30 May 2002

- D.H. Peters, A. Yazbeck, R. Sharma. Better Health Systems for India’s Poor: Analysis, Findings, and Options. 2002; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey Summary, India 1998-99. Bombay: IIPS 2000

- Wagstaff A. Measuring equity in health care financing: reflections on and alternatives to the WHO’s fairness financing index. 2001. Available from: http://www.healthsystemsrc.org. Accessed 21 March 2002

- C. AbouZahr. Measuring maternal mortality: what do we need to know?. M. Berer, T.K.S. Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London.

- K. Hill, C. AbouZhar, T. Wardlaw. Estimates of maternal mortality for 1995. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 79(3): 2001; 182–193.

- A. Jain. Implications for evaluating the impact of family planning programs with a reproductive health orientation. Studies in Family Planning. 32(3): 2001; 220–229.

- R. Sadana. Measuring reproductive health: review of community-based approaches to assessing morbidity. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(5): 2000; 640–654.

- H. Zurayk, H. Khattab, N. Younis. Concepts and measures of reproductive morbidity. Health Transition Review. 3(1): 1993; 17–40.

- O. Campbell. Measuring progress in safe motherhood programmes: uses and limitations of health outcome indicators. M. Berer, T.K.S. Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London.

- United Nations Development Program. Human Development Report 2001: Making Technology Work for Human Development. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001

- UNICEF/WHO/UNFPA. Guidelines for the monitoring and availability and use of obstetric services. New York: UNICEF, 1997

- T. Wardlaw, D. Maine. Process indicators for maternal mortality programs. M. Berer, T.K.S. Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London.

- World Bank. Safe Motherhood and The World Bank: Lessons from 10 Years of Experience. Washington DC: Human Development Network, 1999

- K. Hanson, P. Berman. Private health care provision in developing countries: a preliminary analysis of levels and composition. Health Policy and Planning. 13(3): 1998; 195–211.

- D.H. Peters, A.E. Elmendorf, K. Kandola, G. Chellaraj. Benchmarks for health expenditures, services and outcomes in Africa during the 1990s. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 6(78): 2000; 761–769.

- Misra R, Chatterjee R, Rao S. Changing the Indian Health System: Current Issues, Future Directions. New Delhi: Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, 2002

- A. Mills, R. Brugha, K. Hanson. What can be done about the private health sector in low-income countries?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(4): 2002; 325–330.

- Nandraj S, Muraleedharan VR, Baru RV et al. Private Health Sector in India: Review and Annotated Bibliography. Mumbai: Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes; Foundation for Sustainable Development, Indian Institute of Technology (Madras); Centre of Social Medicine and Community Health, Jawaharal Nehru University (New Delhi), 2001

- J.C. Robinson. Theory and practice in the design of physician payment incentives. Milbank Quarterly. 79(2): 2001; 149–177.

- U.S. Mishra, M. Ramanathan. Delivery-related complications and determinants of caesarean section rates in India. Health Policy and Planning. 17(1): 2002; 90–98.

- Pai MP, Sundaram P, Radhakrishnan KK et al. A high rate of caesarean sections in an affluent section of Chennai: is it cause for concern? National Medical Journal of India 12(4): 156–58.

- K. Ranson, K.R. John. Quality of hysterectomy care in rural Gujarat: the role of community-based health insurance. Health Policy and Planning. 16(4): 2001; 395–403.

- C.A.K. Yesudian. The behaviour of the private sector in the health service market of Bombay. Health Policy and Planning. 9(1): 1994; 72–80.

- Mahal A, Singh J, Afridi F et al. Who “Benefits” From Public Sector Health Spending In India? Results Of A Benefit Incidence Analysis For India. Health, Nutrition, Population Working Paper Series. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2001

- G. Walt, L. Gilson. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 9(4): 1994; 353–370.

- P. Musgrove. Public spending on health care: how are different criteria related. Health Policy. 47(3): 1999; 207–223.

- A. Preker, A. Harding, P. Travis. “Make or buy” decisions in the production of health care goods and services: new insights from institutional economics and organizational theory. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 78(6): 2000; 779–790.

- Mukhopadhyay M editor. Report of the Independent Commission on Health in India. New Delhi: Voluntary Health Association of India Press, 1997

- J.M. Belizan, F. Althabe, F.C. Barros. Rates and implications of caesarean sections in Latin America: ecological study. BMJ. 319: 1999; 1397–1400.

- Self-Employed Women’s Association. Annual Report. Ahmedabad, 2000. Available from: http://www.sewa.org. Accessed 9 July 2002

- Roberts MJ, Hsiao W, Berman P et al. Getting Health Reform Right. Washington DC: World Bank. In press

- Saltman RB, Figueras J. European Heath Care Reform: Analysis of Current Strategies. WHO Regional Publications, European Series, No. 72, 1997

- M.R. Reich. Political Mapping of Health Policy: A Guide for Managing the Political Dimensions of Health Policy. 1994; Harvard School of Public Health: Boston.

- M.R. Reich. The politics of health sector reform in developing countries: three cases of pharmaceutical policy. Health Policy. 32(1-3): 1995; 47–77.

- R. Brugha, Z. Varvasovzsky. Stakeholder analysis: a review. Health Policy and Planning. 15(3): 2000; 239–246.

- S. Nandraj, A. Khot, S. Menon. A stakeholder approach towards hospital accreditation in India. Health Policy and Planning. 16(S2): 2001; 70–79.

- M.E. Khan, J.W. Townsend. Has the Indian Family Welfare Programme Lost Momentum Under the Target Free Approach? Emerging Evidence. 1998; Population Council: New Delhi.

- Loewenson R. Public Participation in Health: Making People Matter. IDS Working Paper No. 4. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, 1999

- T.A. Brennan, D.M. Berwick. New Rules: Regulation, Markets and the Quality of American Health Care. 1996; Jossey-Bass Publications: San Francisco.

- R. Baldwin, M. Cave. Understanding Regulation. 1992; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Busse R, Hafez-Afifi N, Harding A. Regulation of health services. In: Harding A, Preker A, editors. Private Participation in Health Services Handbook. Washington DC: World Bank. In press

- McKinsey & Company. Developing Successful Global Alliances. Seattle: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2002

- D.H. Peters, S. Chao. The sector-wide approach in health: What is it? Where is it going?. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 13(2): 1998; 177–190.

- B. Gray. Collaborating: Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problems. 1991; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco.

- S.M. Shortell, A.P. Zukosky, J.A. Alexander. Evaluating partnerships for community health improvement: tracking the footprints. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 27(1): 2002; 49–91.

- K. Johnson, W. Grossman, A. Cassidy. Collaborating to Improve Community Health: Workbook and Guide to Best Practices in Creating Healthier Communities and Populations. 1997; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco.

- T. Ensor, S. Witter. Health economics in low income countries: adapting to the reality of the unofficial economy. Health Policy. 57(1): 2001; 1–13.

- D.L. Sackett, S.E. Straus, W.S. Richardson. Evidence-based Medicine: How to Practise and Teach EBM. 2nd ed., 2000; Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh.

- A. Mills, R. Brugha, K. Hanson. What can be done about the private health sector in low-income countries?. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(4): 2002; 325–330.

- Waters H, Hatt L, Axelson H. Working with the private sector for child health. Health, Nutrition and Population Discussion Paper. Washington DC: World Bank, 2002