The Bush Administration is increasing its efforts to weaken existing international agreements on sexual and reproductive health and rights, including the Programme of Action of the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) and its five-year progress review (ICPD+5). Hence, at the UN General Assembly Special Session on Children, 8–10 May 2002 in New York, the US delegation – aligning itself with the Holy See, Iran, Iraq, Libya and Sudan – used its superpower status to try to undo the ICPD. Indeed, John Klink, the Holy See’s strategist at ICPD, Beijing and ICPD+5, was this time a member of the US delegation. Fortunately, the US and its allies did not prevail.

More than 60 heads of state and numerous representatives of non-governmental organizations – 3,000 in all from 170 countries – attended the Special Session to review the achievement of goals set at the 1990 World Summit for Children and agree on future actions. For the first time, young people – more than 350 of them – attended a UN conference as participating delegates.

The final document, A World Fit For Children Citation[1], was adopted by consensus after 17 months of strenuous and tense negotiations. It sets out a global action agenda for the health, development and rights of all children (aged under 18). It outlines specific action to be taken to combat HIV/AIDS. It reiterates the central ICPD goal of making accessible, through the primary health care system, reproductive health for all individuals of appropriate ages as soon as possible and no later than 2015 Citation[2]. And it clearly reaffirms international agreements reached at the ICPD and Fourth World Conference on Women (1995) and at their five-year progress reviews. Those agreements richly detail adolescents’ rights to sexual and reproductive health education, information and services Citation[3].

Despite threats to pull out of the negotiations and other forms of retaliation, the Bush Administration could not achieve its goals. For example, it could not secure the inclusion of language promoting “abstinence-only” sex education. Other governments recognized that, the world over, a great many adolescents are already sexually active, not least the millions who are already married or in a stable union. An “abstinence-only” statement would have been very damaging, since there is no evidence that abstinence-only programmes delay sexual initiation or have any value for adolescents who are already sexually active. In contrast, there is evidence that young people who receive comprehensive sexuality education become sexually active later, and are more likely to use contraceptives than those who go through abstinence-only sex education programmes Citation[4]Citation[5]. These facts left the US delegation unmoved, as did the surveys reporting that the vast majority of US parents want their children to receive information in school about a broader range of topics, including contraception, HIV/AIDS, rape and how to handle the pressure to have sex Citation[6].

Prolonged wrangling occurred over whether the phrase “reproductive health services” should, as the US delegation insisted, be redefined to exclude legal abortion. The vast majority of government delegations agreed that reproductive health services for adolescents should remain as defined in the ICPD Programme of Action and in subsequent UN conference agreements. This definition specifies that decisions about abortion services for all women, including adolescents, can only be made at the national level, in accordance with national law Citation[7]. The definition was thus left untouched.

The US delegation was also unsuccessful in its attempts to characterize the family as marriage between a man and woman only. Delegates agreed once again that: “…in different cultural, social and political systems, various forms of the family exist” Citation[8]. Neither could the US insert a statement asserting absolute parental rights to the detriment of children’s rights. Similarly, progressive delegations blocked US efforts to include wording that would have recognized couples’ right to information about family planning, but not access to contraceptives.

In fact, after the adoption of the final text by the UN’s General Assembly, the US issued an extensive “Explanation of Position” restating the Bush Administration’s views on all these elements, presumably because they felt they had lost the battle on these counts.

Success on sexual and reproductive health had a price. The final document is not as inspiring as women’s health and youth advocates, and many governments, had wanted. Much of the detail – e.g. on the content of comprehensive sexuality education programmes – had to be deleted to curtail debate. The phrase “reproductive health services” was also removed from the health section of the document. Nevertheless, the unqualified endorsement of prior UN conferences means that the detailed content of those agreements remains the gold standard, and can be used to garner support for programmes that fulfill adolescents’ sexual and reproductive rights.

Moreover, the final document contains a separate section on HIV/AIDS, which escaped controversy since it reiterates the key agreements on children and adolescents reached only months before at the June 2001 UN Special Session on HIV/AIDS. These include the goal first agreed at ICPD+5 to reduce HIV prevalence among young men and women aged 15–24 in the most affected countries by 25% by 2005, and globally by 25% by 2010 Citation[9]Citation[10]. Also included is a commitment to ensure that by 2005, at least 90%, and by 2010, at least 95% of young people have access to the information, education (including peer education and youth-specific HIV education), and services necessary to develop the life skills required to reduce their vulnerability to HIV infection Citation[11]. Reference to “reproductive health services” was retained in this section, which calls on governments to provide women and adolescent girls “health care and health services, including sexual and reproductive health…” Citation[12].

Sadly, the rights of young people are not affirmed throughout the document as strongly as they would have been, had the Bush Administration agreed to describe the Convention on the Rights of the Child as the framework for A World Fit For Children. With Somalia expected to ratify the Convention shortly, along with East Timor, which has just attained statehood, the US will stand alone among the world’s governments in its opposition to the Convention.

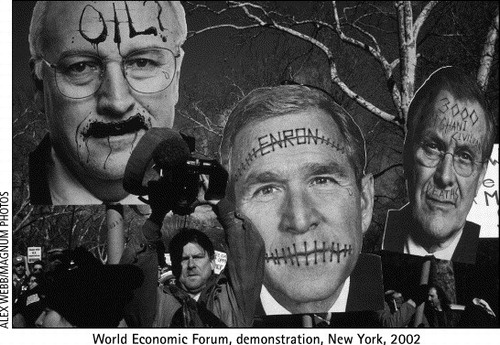

The US was thwarted by governments from around the world, including those from Latin America, the European Union and other industrialized nations such as Canada, New Zealand and Switzerland. Asian and sub-Saharan African countries remained strangely silent throughout negotiations on health issues, but joined the final consensus. The participation of many non-governmental organizations from both the developed and developing world and their concrete, country-based experiences, was also crucial to preventing a rollback. The International Sexual and Reproductive Rights Coalition, comprising 20 organizations and youth networks from around the world, was particularly effective.

Successfully opposing the mighty US proved to be possible, but it was an exhausting and bruising experience for all involved. The Special Session on Children also made clear the need for continued vigilance and mobilization in the months and years to come. A similar US attack on ICPD also took place (unsuccessfully) at the May 2002 World Health Assembly, and another is expected at the August-September 2002 World Summit for Sustainable Development.

References

- United Nations. A World Fit for Children. A/S 27/19/Rev1. New York: UN, 2002

- Op cit [1], para 36 (f)

- Op cit [1], para 37 (3)

- Kirby D. Emerging Answers: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy. Washington DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, 2001

- US Surgeon General David Satcher. Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Promote Sexual Health and Responsible Sexual Behavior. Washington DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 2001. p11

- Schemo DJ. Survey finds parents favor more detailed sex education. New York Times, 4 October 2000. pA1

- United Nations. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development, Document A/Conf. 171/13. New York: UN, 1994. paras 7.6 and 8.25

- Op cit [1], para 15

- Op cit [1], para 46(a)

- United Nations. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Whole of the Twenty-first Special Session of the General Assembly. Document A/S-21/5/Add.1. 1 July 1999. para 70

- Op cit [1], para 47 (2)

- Op cit [1], para 47 (4)