Abstract

Community-based health insurance (CBHI) may be a mechanism for improving the quality of health care available to people outside the formal sector in developing countries. The purpose of this paper is to identify problems associated with the quality of hysterectomy care accessed by members of SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association), an Indian CBHI scheme, and discuss mechanisms that would optimize quality of care. Data on hysterectomy care were collected through a review of 63 insurance claims and semi-structured interviews with 12 providers. Quality of hysterectomy care accessed by SEWA’s members varied from potentially dangerous to excellent. Dangerous conditions included operating theatres without separate hand-washing facilities or proper lighting, the absence of qualified nursing staff, performing hysterectomy on demand, removing both ovaries without consulting or notifying the patient, and failing to send the excised organs for histopathology, even when signs were suggestive of disease. Women paid substantial amounts of money, even for poor and potentially dangerous care. In order to improve the quality of care for its members, a CBHI scheme can: (1) gather data on the costs and complications for each provider, and investigate where these are excessive; (2) use incentives to encourage providers to make efficient and equitable resource allocations; (3) contract with providers giving a high standard of care or who agree to certain conditions; and (4) inform and advise doctors and the insured about the costs and benefits of different interventions. In the case of SEWA, it is most feasible to identify a limited number of hospitals providing better quality care and contract directly with them.

Résumé

L’assurance maladie communautaire (AMC) peut améliorer la qualité des soins dans les pays en développement. Cet article identifie les problèmes associés à l’hystérectomie chez les membres de l’Association des travailleuses indépendantes (SEWA), un projet indien d’AMC, et examine les mécanismes qui optimiseraient la qualité des soins. Les données ont été recueillies en étudiant 63 demandes de remboursement et lors d’entretiens semi-structurés avec 12 prestataires. Les soins dispensés aux membres de la SEWA sont qualifiés de potentiellement dangereux à excellents. Parmi les situations dangereuses, des salles d’opération sans installations séparées pour se laver les mains ou sans éclairage suffisant, l’absence de personnel infirmier qualifié, des hystérectomies sur demande, l’ablation des deux ovaires sans consulter la patiente, et négliger d’envoyer les organes retirés pour histopathologie, même en présence de signes de maladie. Les femmes avaient payé de fortes sommes, même pour des soins médiocres et potentiellement dangereux. Afin d’améliorer les soins pour ses membres, un projet d’AMC peut: (1) recueillir pour chaque prestataire des renseignements sur les coûts et les complications, et déterminer où ils sont excessifs; (2) encourager les prestataires à allouer les ressources équitablement et efficacement; (3) passer des contrats avec des prestataires assurant un niveau élevé de soins ou qui acceptent certaines conditions; et (4) informer les médecins et les assurés des coûts et des avantages de différentes interventions. La SEWA peut identifier un nombre limité d’hôpitaux dispensant des soins de qualité et les prendre sous contrat.

Resumen

Este artı́culo identifica ciertos problemas relacionados con la calidad de la atención de histerectomı́a a que tenı́an acceso las socias de la Asociación de Trabajadoras Independientes (SEWA) – un plan de salud comunitario en la India. Después de revisar 63 solicitudes de reembolso, y entrevistar a 12 prestadores de servicios, se concluyó que la calidad de atención para esta intervención variaba desde potencialmente peligrosa hasta excelente. Entre las condiciones peligrosas se incluı́an la falta de iluminación apropiada en los quirófanos, y de instalaciones aparte para lavarse las manos; la ausencia de enfermeras calificadas; y la extirpación de ambos ovarios sin consultar ni notificar a la paciente. Además no siempre se sometı́an los órganos extirpados a exámenes histopatológicos, aun cuando presentaran signos de enfermedad. Las mujeres pagaron sumas altas, aun cuando la atención estuviera deficiente y potencialmente peligrosa. Para mejorar la calidad de atención que reciban sus socios, un seguro de salud comunitario puede (1) recolectar datos sobre los costos y complicaciones correspondientes a cada prestador de servicios, e investigar aquellos que sean excesivos; (2) ofrecer incentivos que animen a los prestadores de servicios a utilizar los recursos asignados eficiente y equitativamente; (3) contratar a los profesionales de la salud que ofrecen servicios de alta calidad o se comprometen a cumplir ciertas condiciones; (4) informar y orientar tanto a los médicos como a los asegurados acerca de los costos y beneficios de las distintas intervenciones.

Over the last 20 years there has been growing interest in health insurance for the informal sector in developing countries. Community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes (also referred to as micro-insurance and mutual health insurance) involve prepayment for some component of health care and pooling of revenues such that there are cross-subsidies from low-risk to high-risk individuals. CBHI schemes can vary tremendously in terms of their design, management and the nature of the “communities” covered (see Citation[1] for a review of 82 schemes). Policymakers generally see CBHI as a means of improving access to effective health care, and preventing indebtedness and impoverishment as a result of trying to access such care.

A CBHI scheme also has the potential to shape the quality Footnote1 of care accessed by its members. For example, Bennett et al Citation[1] found that “more successful schemes” did take on a more strategic purchasing role, including “selective contracting with providers and use of essential drug lists, to help ensure quality of care”. CBHI might prove helpful in addressing poor quality and inefficiency in India’s health care system. Health care in India is largely privately financed (75% of all health expenditures are private) and privately provided (80% of allopathic doctors and 57% of hospitals are in the private sector) with minimal government regulation Citation[3]. This system pays providers more for doing more, whether or not there is any evidence more is beneficial to the patient. Because there is regulation of neither the quality nor the price of medical care, the system may pay more for poor quality.

The purpose of this paper, based on a small, preliminary study, is first, to identify problems associated with the quality of hysterectomy care accessed by members of an Indian CBHI scheme, the Self-Employed Women’s Association’s (SEWA) Medical Insurance Fund. Since 1992, SEWA has operated a voluntary Medical Insurance Fund for its members. Secondly, it will discuss mechanisms that might be put in place by SEWA, and community-based insurance schemes more generally, to optimize quality of health care.

Hysterectomy was chosen as a tracer of quality for two main reasons. First, hysterectomy is the single most common cause of hospitalization for which SEWA members submit claims Footnote2. Secondly, the technical quality of hysterectomy care is highly important, given the potential benefits and risks of this procedure. Benefits of hysterectomy may include prolongation of life, e.g. when it used to rid the body of cancer of the cervix or uterus. Quality of life may be enhanced if hysterectomy is used to cure irregular or painful menstruation, or to provide relief from a prolapsed uterus. However, the risks of this major surgery include intra-or post-operative death and nonfatal complications, such as urinary tract infection, incisional hernia, sepsis, intestinal obstruction, coronary artery disease, depression and other psychiatric problems Citation[4].

SEWA’s medical insurance fund

SEWA is a union for women working outside the formal sector, with 68% of its 215,000 members residing in Gujarat. SEWA’s Integrated Social Security Scheme was initiated in 1992. This Scheme provides life insurance, medical insurance and asset insurance (against the loss of house or working capital in case of flood, fire or communal riots). In order to join the Medical Insurance Fund, women must be between 18 and 58 years of age. Those who pay the yearly Social Security Scheme membership fee of 72.5 rupees (30 rupees of which is earmarked for medical insurance) are covered to a maximum of 1200 rupees yearly in case of hospitalization. Women also have the option of becoming Lifetime Members of the Social Security Scheme by paying 700 rupees. Special benefits to which only the Lifetime Members are entitled include: maternity benefit of 300 rupees with the birth of each child; reimbursement for cataract surgery up to 1200 rupees; reimbursement for a hearing aid up to 1200 rupees; and, reimbursement for dentures up to 600 rupees. Exempted from coverage are certain chronic diseases (for example, chronic tuberculosis, certain cancers, diabetes, hypertension, piles) and disease caused by addiction.

The choice of provider is left entirely to the discretion of the SEWA member. They are eligible for reimbursement whether they use private for-profit, private non-profit (i.e. trust or charitable) or public facilities. At the time of discharge from hospital, the SEWA member is required to pay the full bill out-of-pocket. The insured must then submit to SEWA the following documents within a three-month period: a doctor’s certificate stating the reason for hospitalization and the dates of admission and discharge; doctors’ prescriptions and bills for medicines purchased; and reports of laboratory tests done during the hospital stay. After submission of these documents, the member is usually visited by a SEWA employee who verifies the authenticity of the claim. All documentation is reviewed by a consultant physician (to assess for fraudulent claims, or cases of chronic disease, but not the quality or appropriateness of the services provided), and a final decision on the claim is then made by an insurance panel. Finally, the SEWA member is notified of the panel’s decision and, when applicable, is paid by cheque. Of approximately 1930 claims submitted in Gujarat between 1994 and 2000, 89% were approved for reimbursement.

Throughout the ten districts of Gujarat where it operates, the Medical Insurance Fund had 23,214 members (47% lifetime, 53% annual) in 1999–2000. Statewide, coverage by the Medical Insurance Fund was 16% (23,214 insured among 147,600 SEWA members). It is very difficult to estimate the costs of administering the Medical Insurance Fund; many of the administrative functions are shared with the life and asset insurance components as well as with other activities of SEWA. A recent study by the International Labour Organization found that basic administration costs accounted for 9.3–19.7% of SEWA’s Integrated Social Security Scheme expenses annually (Michaela Balke, ILO, personal communication).

Study methodology

This study was carried out in August, 2000. It focused on providers who had performed hysterectomies on the 63 SEWA members in Kheda District who had submitted claims from July 1994 to August 2000. Quality was assessed based on Donebedian’s “structure, process, outcome” approach Citation[5]. Structure refers to the availability of inputs or infrastructure necessary to provide good quality care. The key aspects of structure examined were the availability of staff and equipment. Process refers to the procedures of delivering care, in particular the correctness of the diagnosis and choice and process of delivering a therapeutic regime. Here we assessed the appropriateness of performing hysterectomy (and oophorectomy), patterns of pre-, intra-and post-operative care, and the processes of information sharing and decision-making. Outcome, which is the achievement of the expected improvement in health status, could not be assessed in this study. Data on the cost of hysterectomy care was also collected.

Relevant information was first obtained directly from the insurance claims, including: age of claimants, cost of hospitalization, type of provider (public, private non-profit or private for-profit) and providers’ contact details. In order to compare monetary amounts for different years (for example, data on income and cost of treatment), values have been standardized to 1999/2000 Indian rupees. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflators for India Citation[6] were used in these calculations.

The number of hysterectomies performed by each provider in the database was tallied. The authors, with the help of two research assistants experienced in qualitative research and fluent in Gujarati (the local language), sought to visit all providers who had operated on three or more SEWA patients. Three methods of data collection were used: (1) semi-structured interview; (2) a visit to operating theatre and ward; and (3) where available, a review of at least one in-patient medical record. The semi-structured interview was designed to collect information in the following domains: provider characteristics (regarding staff and operating facilities); pattern of care provided to hysterectomy patients during the pre-operative, operative and post-operative periods; the process of information sharing and decision-making; and fees charged. All interviews were conducted in the providers’ facilities. Data collected during visits to the wards and operating theatres was limited to presence of: scrub room, dome light, operating table, Boyle’s apparatus, autoclave and air-conditioning. In-patient records were reviewed to validate the course of pre-operative, operative, and post-operative care as described by the provider.

A single focus group discussion was held among ten SEWA members in order to explore their perceptions of the hysterectomy procedure and hospital care available in Kheda District.

Participants

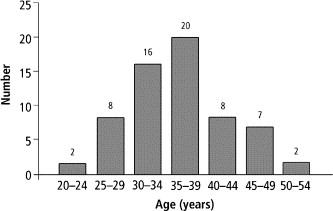

The average age of the 63 hysterectomy claimants was 35.32 years (median 35; age distribution shown in

). The average duration of hospitalization was 9.1 days (median 8 days). Four of the claims were for care at a public hospital, six claims were for care at three different private non-profit hospitals, and the remaining 53 claims were for care at 27 different private for-profit hospitals (Table 1 For each provider, the number of hysterectomy claimants, their average age and income, duration of hospitalization, cost of hospitalization, and amount reimbursed

Twelve of the 31 providers were interviewed (see ), representing 39 of the total 63 SEWA members operated on (62%). No provider refused to be interviewed. Of the eight providers who had performed three or more of the surgeries, seven were interviewed.

Of the 12 doctors interviewed, nine worked in private for-profit hospitals, two in private non-profit (mission) hospitals and one in the public hospital. Seven of the providers were diploma or degree holders in gynaecology, while the remaining four (all of them in private for-profit facilities) were general surgeons.

Structure: staff and equipment

The number of beds in each private for-profit hospital ranged from 10 to 60, whereas the number of beds in private non-profit hospitals and the public hospital ranged from 75 to 150. The bed to staff ratio (including full-time physicians, nurses, administrative, cleaning and other support staff) ranged from 1.3 to 4.3 at private for-profit facilities, 0.9 to 1.1 at private non-profits, and 3.6 at the public hospital. Neither the private for-profit hospitals nor the public hospital employed qualified nurses (that is, nurses with any formal training) but used “nurses” who had received on-the-job training. Both of the private non-profit facilities had approximately one qualified nurse for every four in-patient beds.

The operating theatres at the private non-profit hospitals and the government hospital all had at least one scrub room, dome light, Boyle’s apparatus and air-conditioner. This equipment was also possessed by three of the private for-profit hospitals. Operating theatres in five of the private for-profit hospitals were without scrub room, four without dome lights (simple fluorescent tube lights or floor lamps were used), four without Boyle’s apparatuses, and two without air-conditioning. No single operating theatre was lacking in all four amenities.

Process: hysterectomy (and oophorectomy) performed only when medically indicated?

The general surgeons admitted that they would perform surgery in the absence of signs or symptoms of disease, on request by the patient (as discussed below, it is common for women to request hysterectomy for non-medical reasons). The gynaecologists generally acknowledged that it was unhealthy practice to remove the uterus unnecessarily, however, most performed the surgery “on demand” as patients denied surgery (and instead offered medical treatment) would simply present to another hospital requesting the operation. Only the gynaecologists in the two private non-profit hospitals reported denying surgeries to those who did not seem to have underlying disease.

Three of the five general surgeons routinely removed both ovaries, while one removed a single ovary in every case (“the left ovary is left”), and another removed ovaries only in women older than 35 years. The gynaecologists reported performing bilateral oophorectomy in 10–30% of all cases, and rarely before the age of 40 or 45 years.

Process: pre-operative, intra-operative and post-operative care

Table 2 Worst-case (private general surgeon) and best-case (trust hospital gynaecologist) protocols

All providers claimed to perform history, physical and vaginal examination when the patient first presented. Ultrasound was available in five of the nine private for-profit hospitals as well as the two private non-profit hospitals. Approximately half of providers reported occasionally performing cervical smear, generally when cervical erosions were seen on vaginal examination. None of the doctors reported routinely performing diagnostic dilatation and curettage (some cited high cost as the reason, others the refusal of patients to undergo a trial of conservative, or medical, management for their complaint).

All of the general surgeons stated that they would admit and operate on the same day. The gynaecologists generally reported admitting 24 or 48 hours prior to the procedure so as to conduct pre-operative tests and to prepare the patient for surgery. At all providers, blood tests and urine microscopy were routinely performed. Only when patients were willing to pay extra were tests such X-ray, HIV test, or ECG (ultrasound) performed. Generally, providers would not operate unless haemoglobin was at least 8 or 8.5. However, chart review revealed surgeries being performed with haemoglobin as low as 6.4 (in this case, the general surgeon stated that haemoglobin was not so important given that “little blood was lost during this [hysterectomy] procedure”). HIV testing was performed routinely at the two private non-profit hospitals.

The number of hysterectomies performed per operating doctor per year ranged from 35 to 180 (both of these were gynaecologists in private for-profit hospitals). The general surgeons performed abdominal hysterectomies only. The gynaecologists performed abdominal hysterectomies except in the case of prolapsed uterus, where vaginal hysterectomies were performed. The reported duration of surgery varied from 30 minutes to 2.5 hours. All of the providers reported having at least one sterile (or “scrubbed”) assistant available during the surgery, in addition to a (“non-scrubbed”) floor assistant.

None of the doctors reported routinely sending the excised uterus (or ovaries) for histopathology, even when the patient presented with signs or symptoms suggestive of disease. The doctors stated that patients were not willing to pay the 150 to 400 rupees charged for histopathology examination.

Post-operatively, a minority of the doctors routinely gave oral iron, calcium and/or gastro-protective agents (to protect the stomach from the analgesic medications). A single follow-up appointment was generally scheduled for four to ten days after discharge.

Process: information sharing and decision-making

All of the doctors commented that a certain percentage of patients requested hysterectomy even in the absence of signs or symptoms of gynaecologic disease. Similarly, they reported that women who had signs or symptoms of disease were often unwilling to undergo a trial of conservative (that is medical) management. It is not clear the extent to which doctors tried to discourage (or encourage) unnecessary hysterectomies, or warned patients about the potential complications.

A complex variety of social, cultural, economic and medical factors seemed to underlie the willingness to undergo hysterectomy. As reported in the focus group discussion, it was the tradition in some households that, during menstruation, a woman was not permitted to enter temples, to cook for her family, and more rarely, to enter the house. Women felt that avoidance of such problems may in some cases justify hysterectomy, but agreed that the decision whether to go for hysterectomy was ultimately made by the doctor:

“The doctor gives advice that, ‘You will have to get it (the uterus) removed, then you won’t have any problems again.’ So we have to do it.”

The women acknowledged that doctors (particularly private for-profit) had an interest in performing unnecessary hysterectomies:

“There are doctors who do it for money only … Yes. It is there in many places. At many places they do the operation for money. Nobody gives true advice. If we go to the government hospital, then we get good advice. But not in the private hospital.”

None of the doctors consult the patient about oophorectomy pre-operatively, and often they do not inform her post-operatively that the ovaries have been removed. The argument given by doctors in favour of “blanket oopherectomy” was that this helps the woman by preventing future ovarian disease. These same doctors downplayed the potentially harmful consequences of early removal of the ovaries. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was never prescribed by the general surgeons, and only rarely by the gynaecologists. Reasons cited for not prescribing HRT included high cost to the patient, limited patient compliance, and, “Indian women never have complaints related to this”.

Only one of the five general surgeons routinely provided a discharge summary, compared with six of the seven gynaecologists. The instructions provided to the patient at the time of discharge varied considerably. Most, though not all, of the doctors advised the patient to refrain from heavy lifting (for anywhere between two weeks and three months). Very few of the doctors advised the patient about sexual intercourse (at least one doctor told patients to abstain for three months).

Cost

Among the 63 surgeries for which claims were submitted to SEWA, the average official cost (based on receipts for bed fees, doctors’ fees, medicines, and lab fees) was 5010 rupees (median 5292 rupees), and average reimbursement 1277 rupees (median 1307 rupees). Data suggest that the cost of hospitalization in public facilities was less than in private facilities, and that there was little difference between private for-profit and private non-profit (see ).

Providers reported that the cost of surgery and hospitalization (inclusive of medicines and tests) was generally tailored to the socio-economic status of patients. For the poorest patients, the cost varied from 3210 rupees at the government hospital (this included drugs purchased outside the hospital and bribes or “unofficial gifts” of 500 rupees) to 6000 rupees at one private non-profit hospital. For the wealthiest patients the cost was as high as 15,000 rupees; this higher cost was accounted for primarily by extra laboratory tests and “special room” charges (special rooms are typically private with air-conditioning and attached bathroom).

On average, the fees were highest among gynaecologists at private non-profit hospitals (5500 rupees), followed by gynaecologists at private for-profit hospitals (5100 rupees), and were lowest among the general surgeons at private for-profit hospitals (4300 rupees).

Discussion: what can be done?

Weaknesses of the current study include its small size, and the focus on structure and process indicators of quality as opposed to outcomes, for example, the frequency of medical complications following hysterectomy. While structure (staff and equipment) could be assessed fairly objectively, data on process were collected through provider in-depth interviews, and hence may be prone to bias. More objective but time-and resource-intensive measures of process might involve direct observations (for example, of the hysterectomy surgery itself, or pre-operative visits) or more thorough review of medical records (not available for most of the facilities studied).

This study suggests that the quality of hysterectomy care among SEWA’s members varies tremendously, from potentially dangerous to excellent. This variation is present in both structure and process indicators of quality. Seemingly dangerous aspects of structure included operating theatres without separate hand-washing facilities or proper overhead lighting, and the absence, in the majority of facilities, of qualified nursing staff. Dangerous aspects of process included performing hysterectomy on demand without diagnostic work-up; removing both ovaries without consulting (pre-operatively) or notifying (post-operatively) the patient; and failing to send the excised uterus (and ovaries) for histopathology, even when symptoms and signs suggested underlying disease. These dangerous practices seem (with the exception of oophorectomy) geared towards increasing the number of procedures performed and keeping costs to the provider down. In general, it can be concluded that the standard of care was higher among the gynaecologists than the general surgeons. Given the small size of this study, it is impossible to make conclusions regarding the relative quality of care provided by public versus private facilities. The cost of a hysterectomy was higher when provided by a gynaecologist versus a general surgeon, suggesting that there may in this setting be an association between higher price and better quality. Many women are, however, paying substantial amounts of money for care of poor, and potentially dangerous, quality.

There are problems both on the patient and providers sides, for which it may be difficult to improve quality of hysterectomy care in Kheda District. For patients, decisions around whether, when and where to have a hysterectomy are difficult, given the imperfect information available to them. In general, “the consumer (of health care) is unlikely to have good information about her own health, what treatments are available, what the effectiveness of treatment is likely to be and what the cost of treatments will be” Citation[7]. This lack of information is exacerbated in rural Gujarat, where the literacy rate of women older than six years of age is only 49% Citation[8] and where decision-making is complicated by the domestic, religious and economic implications of hysterectomy. Ideally, the woman should be able to rely on her physician to make a well-informed decision that is in her best interest. However, providers may not know what is the most efficient rate or quality at which hysterectomy surgeries should be performed. For example, a study by McPherson et al Citation[9] found a more than two-fold variation in age-standardized hysterectomy rates between hospital service areas in the US (New England), Norway and England. Furthermore, it may be difficult for a doctor to make a decision in the patient’s best interest when there are financial incentives to do otherwise. For example, a doctor who is paid out-of-pocket by patients for each hysterectomy performed may be inclined to encourage women to have hysterectomies even in the absence of indications.

For more than eight years, the SEWA Medical Insurance Fund has been running in Kheda District. Having acknowledged that it is difficult to establish what the ideal rate and quality of hysterectomy care is, why has SEWA failed at least to protect its members from the dangerous practices described above? Several factors seem to be responsible for this:

| • | SEWA has not attempted to monitor the frequency or quality of care provided to its members. | ||||

| • | SEWA does not actually act as an intermediary (financial or otherwise) between the purchaser and provider, and thus has had no influence on provider behaviour. | ||||

| • | Levels of reimbursement under the SEWA scheme are low relative to the cost of hospitalization, and are not conditional on the hospitalization being necessary or an acceptable level of quality. Thus, the scheme appears to have done little to direct consumer behaviour. | ||||

What things might a CBHI scheme do to optimize the quality and efficiency of the care it finances? The community-based insurer must be a strategic purchaser of health care (i.e. must serve as the financial intermediary), attempting to influence the behaviour of both providers and consumers so as to maximize quality and efficiency while at the same time keeping costs under control Citation[10]Citation[11].

First, the insurer must establish guidelines as to what constitutes efficient care, and gather data on outcomes and resource use for each provider (physician profiling). For example, “a good insurance-based information system would be able to compare referral rates by different doctors and investigate those cases where excessive referrals seem to have been made” Citation[1]. Similarly, an information system should allow comparison of costs and outcomes for a certain intervention across different providers. Cases where costs or complications are excessive could then be investigated. For SEWA, as for other CBHI schemes, it would be relatively easy to collect and compare data on costs. However, it would not be feasible for SEWA to collect provider-specific information on outcomes, given that myriad different providers are used under the scheme, and the beneficiary population would be difficult to contact in follow-up as they live in villages over a very wide area. It might be feasible and useful for SEWA to monitor structure and process aspects of care by more thoroughly reviewing receipts that are being submitted, and perhaps by requiring doctors to submit a copy of the in-patient record.

Secondly, “insurers should take a very active role in establishing institutional mechanisms that encourage providers of health services to make efficient and equitable resource allocation decisions” Citation[12]. Perhaps most important here is determining the method by which doctors and other health care providers will be remunerated for their services. Mooney Citation[7] states, “… while we know we can influence what doctors do by changing the financial and non-financial incentives they face, there is (1) too little recognition of this as a policy tool in health care; (2) too little information about just what the impact of different incentive and remuneration systems is on doctors’ behaviour; and (3) too little thought given to trying to decide what societies want their doctors to do anyway!”

Different methods of payments present providers with different incentives and each of the methods has its strengths and weaknesses. For example, a doctor who is paid by salary to provide hysterectomy care might try to limit the number of patients he sees, as well as the time spent with each patient. A doctor paid by fee-for-service has the incentive to perform as many surgeries as possible, and if there is no constraint in the purchaser’s ability to pay, to use the best available surgical technology, drugs, accommodation, etc. Payment mechanisms can be combined (for example, a doctor can be paid by salary that is topped-up with a fee for each service provided), they can vary from one disease or intervention to another, and they may need to be adjusted periodically based on experience. SEWA, if it is to have any significant impact on quality of care, will need to become an intermediary between patients and providers. However, if SEWA is to use any method of payment other than fee-for-service (for example, capitation, fixed budget or case payment) then it will almost certainly have to restrict the number of health care providers in order to make this administratively feasible.

Thirdly, the insurer should contract with providers who will be responsible for caring for the insured. Limiting the number of providers may allow the insurer to take advantage of economies of scale and physician experience, and may facilitate the gathering of data (say on rates and quality of procedures). Perhaps the biggest problem with limiting the number of providers is that it may hinder geographic access among the insured, particularly those who live farthest from the facilities. At the extreme, the community-based insurer may provide the health care services itself (known as the direct pattern of insurance). Or, in countries like India, where there is a large and active private sector, the insurer might merge, or contract, with a single existing provider. Under the indirect system of insurance, the third-party insurer reimburses a separate health care provider for its services. The insurer should contract selectively with providers who are observed (retrospectively) to provide a high standard of care or those who (prospectively) agree to certain conditions. Conditions might include following standard treatment protocols, a rational referral process and/or drug formularies. Even under such a scheme, ongoing monitoring of volume and quality of services would have to be conducted. Given that many hospitals already operate in Kheda District and Gujarat, it would not make sense for SEWA to establish its own system for delivering hospital care. However, SEWA could contract with a limited number of hospitals. Most feasibly, SEWA could identify providers of better-quality care through small-scale research like this study of hysterectomy care. Having limited the number of providers, SEWA could then monitor process and outcome indicators, and renew contracts periodically (annually or biennially) based on satisfactory performance. The process of identifying, contracting with and monitoring a group of providers would require that SEWA build up (or hire on a temporary basis) individuals with expertise in medical outcomes and contracting.

Fourthly, the insurer can inform and advise both doctors and the insured about the costs and benefits of different interventions. For example, SEWA can educate its own members around the indications for and complications of hysterectomy. This would be a useful adjunct to some of the aforementioned purchasing strategies. Alone, however, it is probably unrealistic to expect this largely illiterate group of women to absorb and act on technical information. Under the current SEWA scheme, the fact that patients and providers are dispersed geographically also makes education difficult.

As an initial step towards monitoring and improving quality of care, SEWA recently established a monitoring and evaluation cell and there are plans to establish a research cell. Activities to date have focused on entering the insurance claims into a computer database. Activities of the research cell may include: more carefully reviewing incoming claims, receipts, and where available, inpatient records; more systematically monitoring outcomes, including consumer satisfaction with hospital care and medical complications resulting from hospitalization; and identifying hospitals that provide high quality care (at least one per district). The research cell, which will consist of at least two full-time researchers (one of them most likely a medical doctor), will be partly funded by external donors. At present, it is not clear what the administrative costs of this research cell will be, or whether its cost can ultimately be incorporated into members’ premiums. The complexity and cost of monitoring quality of care and medical outcomes are likely to be high, given that subscribers to SEWA’s Integrated Social Security Scheme are fairly widely scattered among ten districts. In other situations, where the CBHI scheme is based on a smaller geographic area (for example, a village-or district-based scheme) more intensive interventions might be feasible.

Conclusions

A well-designed and managed community-based health insurance scheme should serve to improve the quality of health care available to people outside the formal sector in developing countries. This study of hysterectomy care provided to a group of insured women in rural Gujarat found that: (1) the quality of care can vary from excellent to dangerous; (2) women spend a substantial amount of money on hysterectomy care of poor quality; and (3) for a variety of reasons, SEWA’s Medical Insurance Fund has had minimal impact on quality of care. In order to improve the quality of care available to its members, SEWA must take on a strategic role in purchasing health care. Most feasibly, this would involve identifying a limited number of hospitals providing better quality care and contracting directly with them. Future research should: (1) help community-based insurers to establish the most cost-effective rate and means of delivering different interventions; and (2) determine the mechanisms (for example, different modes of provider reimbursement, drug formularies, practice guidelines, patient and provider education) most cost-effective in ensuring that providers deliver care of acceptable quality and cost.

Postscript 2002 by M Kent Ranson

Almost two years have passed since this study was conducted. During that time, SEWA has taken some small steps toward improving the quality of inpatient care, and hysterectomy care in particular, available to its members. First, in Kheda district, SEWA’s village-level representatives and members were provided with information on the medical indications for hysterectomy and the potential complications that can arise from this major surgery. Importantly, they were also provided with information about alternative forms of birth control. Since then, the frequency of insurance claims for hysterectomy as a percentage of all claims has dropped from 15% in 1994–2000 to 11% in 2000–2001, though it is not clear to what extent this drop can be attributed to the education of members.

A second major initiative has been the development of a state-wide computerised Management Information System (MIS) into which every insurance claim is entered soon after a decision on the claim has been made. The database is analysed at regular intervals, with some very revealing results. For example, analysis showed the decline in hysterectomy cases in Kheda district described above and highlighted geographic differences in the frequency of hysterectomy claims. In 2000–2001, for example, while hysterectomies accounted for 11% of claims (10 out of 92 claims) in Kheda district, which is largely rural, the proportion was only 2% of claims in Ahmedabad city (6 out of 295 claims). The database still does not include any indicators of quality of health care, however.

Third, SEWA administrators have met with provider-based associations in Ahmedabad city, where the Integrated Insurance Scheme has approximately one-third of its members. It is likely that the Ahmedabad Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Association (AOGA) will ask its members to voluntarily “adopt” wards of Ahmedabad city. The AOGA member in each ward would agree to provide a certain standard of care, set by the AOGA, and would provide care to SEWA members at a concessionary rate. In return, SEWA would recommend that its members use these “preferred providers”, and ultimately might pay these providers directly for care provided to insured members.

While they appreciate that poor quality of inpatient care remains an important problem, SEWA administrators have not yet taken the bolder step of restricting reimbursement to a panel of approved health care providers. This is the approach that has recently been taken by Tribhuvandas Foundation, Gujarat’s other large community-based health insurance scheme. SEWA administrators worry that their insured members would suffer as a result of reduced freedom of choice, and that accessibility of health care, particularly in rural areas, would be reduced. Instead, they have opted to try and test the interventions described above.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank members of the Self-Employed Women’s Association for their support and Prof Anne Mills, Dr Amie Cullimore and Ms Mirai Chatterjee for stimulating review comments. Thanks to Ms Swati Vyas and Ms Dimple Save for their research assistance. This research was supported by the Department for International Development, UK.

Notes

☆ Reprinted with kind permission of Oxford University Press from Health Policy and Planning 2001;16(4):395–403 (slightly adapted).

1 We use the term quality as defined by Donabedian Citation[2]: “Quality shall mean a judgement about the goodness of both technical care and the management of the interpersonal exchanges between client and practitioner.”

2 A separate study by one of the co-authors (MKR) found that more than 15% of claims (63 of 417) submitted in Kheda District from July 1994 to August 2000 were for hysterectomies.

References

- Bennett S, Creese A, Monasch R. Health insurance schemes for people outside formal sector employment. Geneva: World Health Organization, Division of Analysis, Research and Assessment, 1998

- A Donabedian. Reflection on the effectiveness of quality assurance. R.H Palmer, A Donabedian, G.J Povar. Striving for Quality in Health Care: An Inquiry into Policy and Practice. 1991; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 59–128.

- R Bhat. Characteristics of private medical practice in India: a provider perspective. Health Policy and Planning. 14: 1999; 26–37.

- S.I Sandberg, B.A Barnes, M.C Weinstein. Elective hysterectomy: benefits, risks and costs. Medical Care. 23: 1985; 1067–1085.

- A Donabedian. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. 1980; Health Administration Press: Ann Arbor MI.

- International Monetary Fund. International Financial Statistics Yearbook. Washington DC: IMF, 1999

- G Mooney. Key Issues in Health Economics. 1992; Harvester Wheatsheaf: London.

- Government of Gujarat. Health Review, Gujarat, 1995–96. Gandhinagar: Government of Gujarat, 1996

- K McPherson, J.E Wennberg, O.B Hovind. Small-area variations in the use of common surgical procedures: an international comparison of New England, England, and Norway. New England Journal of Medicine. 307: 1982; 1310–1314.

- A.C Enthoven. On the ideal market structure for third-party purchasing of health care. Social Science and Medicine. 39: 1994; 1413–1424.

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO, 2000

- J Kutzin, H Barnum. Institutional features of health insurance programs and their effects on developing country health systems. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 7: 1992; 51–72.