Abstract

This paper analyses the impact of decentralisation on the political organisation, management and provision of sexual and reproductive health services in Ghana. It draws on qualitative research and interviews with key informants from the Ministry of Health, donors, NGOs, regional and district health management teams, local government and community leaders. Within a national reproductive health policy framework, previously disparate family planning, maternal and child health, STI and HIV/AIDS programmes have become more integrated, and donors have pooled or co-ordinated their funding. Some decision-making about resource allocation is meant to happen at district and regional level but in practice, this remains centrally controlled, which may be a necessary safeguard for sexual and reproductive health services. Earmarked donor funds still ensure a regular supply of contraceptives and STI drugs. However, paying for these is problematic at local level. Sexual and reproductive health staff make up a large proportion of primary health care staff, but especially in rural areas they experience poor working conditions, and there is high turnover and vacancies. District and sub-district level links are working well in this new system, but clarity is still needed on how different national sexual and reproductive health bodies relate to each other and to regional and district health authorities. The development of formal mechanisms for priority setting and advocacy at local levels could help to secure benefits for sexual and reproductive health care.

Résumé

Cet article analyse l'impact de la décentralisation sur l'organisation politique, la gestion et la prestation de services de santé génésique au Ghana. Il s'appuie sur des recherches qualitatives et des entretiens avec des informateurs du Ministère de la santé, des donateurs, des ONG, des équipes de gestion au niveau régional et de district, des responsables locaux et communautaires. Des programmes disparates de planification familiale, de santé maternelle et infantile, d'IST et de VIH/SIDA ont été intégrés dans un cadre national de santé génésique et les donateurs ont coordonné leur financement. Certaines décisions sur l'allocation des ressources qui devraient être prises au niveau régional et du district demeurent contrôlées centralement, ce qui peut être une précaution nécessaire pour les services de santé génésique. Les fonds réservés par les donateurs garantissent un approvisionnement régulier de contraceptifs et de médicaments pour les IST. Le personnel de santé génésique représente une forte proportion du personnel de soins de santé primaires, mais, surtout en zone rurale, les conditions de travail sont mauvaises, avec un fort taux de rotation. Les liens entre le district et le sous-district fonctionnent bien dans ce nouveau système, mais il faut clarifier les relations entre les organes nationaux de santé génésique et les autorités sanitaires régionales et de district. La création de mécanismes locaux de définition des priorités et de plaidoyer pourrait être bénéfique pour les soins de santé génésique.

Resumen

Este artı́culo analiza el impacto de la descentralización sobre la organización polı́tica, gestión y provisión de servicios de salud reproductiva en Ghana. Se basa en la investigación cualitativa y en entrevistas con informantes claves del Ministerio de Salud, organismos donantes, ONG, equipos de gestión en salud regionales y de distrito, y dirigentes comunitarios y de gobierno local. Una polı́tica nacional de salud reproductiva ha integrado programas de planificación familiar, salud materno-infantil, ITS y VIH/SIDA, y los organismos donantes han cooperado para coordinar el financiamiento. Algunas decisiones tocante a la distribución de recursos deben tomarse a nivel regional o de distrito, pero en la práctica siguen siendo controladas a nivel central, lo cual puede ser necesario para salvaguardar los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva. Los fondos restringidos todavı́a aseguran un abastecimiento regular de anticonceptivos y medicamentos. Una proporción significativa del personal de salud primaria presta servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva, pero las condiciones de trabajo son deficientes, especialmente en las áreas rurales, y hay mucho recambio. Los vı́nculos de distrito y sub-distrito funcionan bien en el sistema nuevo, pero falta claridad acerca de la relación entre las distintas entidades nacionales de salud salud y entre ellas y las autoridades regionales y de distrito. El desarrollo de mecanismos formales para fijar prioridades y para la promoción a nivel local podrı́an ayudar a obtener beneficios para la atención en salud sexual y reproductiva.

The Cairo International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD, 1994) acknowledged the need for reproductive health services to address a broader range of sexual and reproductive health issues. The Cairo approach was defined by a number of underlying principles such as equity, client-centredness, gendered democratisation, accountability and sustainability, as well as reaffirming access, quality and effectiveness of services. Moreover, Cairo suggested mechanisms by which these could be achieved, namely multi-sectorality, community involvement and comprehensive service delivery. Parallel to the post-Cairo discourse there has been much talk and debate about how the range of health sector reforms being seen across the globe is affecting sexual and reproductive health services. Interestingly, and perhaps surprisingly to some, many of the aims and mechanisms of reforms, in particular decentralisation, are mirrored in the Cairo approach.

Health sector reform and reproductive health debates have developed largely independently of each other and with distinct groups of actors.Citation1 Despite the apparent incompatibility of the economic and efficiency goals of reforms with the individual welfare and rights concerns of sexual and reproductive health, there are many shared values and common approaches. For example, where Cairo called for democratisation of power, health systems reforms have been concerned with better governance and involvement in civil society promoting devolution of power. The ICPD underlined principles of client-centredness and participation; decentralisation is intended to bring greater accountability to communities. The Cairo approach requires linkage with other sectors and actors; decentralisation offers greater opportunities for partnership with NGOs and other locally appropriate actors and other reforms explicitly promote public–private partnerships.

It appears then that decentralisation could provide a means of furthering post-Cairo sexual and reproductive health service delivery. Whether it is doing so is a question that is being asked frequently, yet there have been few analyses of what the decentralisation of health services would mean for sexual and reproductive health. This paper provides a case study of the experience of decentralisation in Ghana vis-à-vis sexual and reproductive health services.

Methods

Data for this paper are based on a multiple-level qualitative case study undertaken in Ghana between 1996–98 with follow-up visits made in 1999 and 2002. The research involved a variety of methods, including policy analysis, document analysis, key informant and semi-structured interviews with policymakers, donors, managers, service providers and service users. National key informants were identified from lists of participants at policy discussion meetings and key conferences, and furthered using snowball techniques (asking each interviewee to recommend other key informants). At regional, district, sub-district and facility levels, interviewees were purposively sampled from official lists according to position (rank and cadre). The research analysed the processes involved in developing and implementing sexual and reproductive health-related policies, with particular focus on changes in district health systems and the evolving relationships between the centre, regional authorities and districts, and between the health sector and other sectors.

At the national level in-depth, non-structured interviews (using a topic checklist rather than structured questions) were conducted with 93 key informants from the Ministry of Health (MoH), other Government Ministries, donors, international and local NGOs, national professional organisations and mission groups. At regional level 25 semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions were conducted with representatives from the Ministry of Health, other sector ministries (particularly Local Government), NGOs, church missions and community leaders in the Upper East Region. District Directors from all six districts in the Upper East were interviewed and a further 37 semi-structured interviews and informal conversations were held in Bawku-West district and Binaba-Zongoire sub-district with representatives from health management teams, local government (District Assembly) and other government sectors, NGOs and missions working locally, and community leaders. At each level the interviews sought to draw out the linkages between the Ministry of Health and other sectors and organisations in the decentralised system, and to document the perceptions of actors at the different levels with regard to what decentralisation could offer sexual and reproductive health services. Structured and semi-structured interviews (using open and closed-ended questions) were conducted with 87 clinical staff and facility managers at 27 facilities purposively sampled by type and location throughout the Upper East Region. The results of structured facility-level interviews and service delivery analysis have been discussed elsewhereCitation2 Citation3 and are not presented here.

Analysis of policy- and management-related documentation took place at four organisational levels (national, regional, district and sub-district) including flows of resources between them, finances and reporting, and clinic-level inventories at the 27 facilities. The purpose of this was to map the routes of key organisational and logistic inputs through the system and to analyse the impact of this on SRH services. International literature on Ghana and the decentralisation process was also reviewed.

Defining and analysing decentralisation

There are three main models of decentralisation: deconcentration, delegation and devolution.Citation4 Some also include privatisation, but this is heavily disputed since under this model services are not retained within the public sector. Deconcentration involves a shift of power from central offices to peripheral offices of the same administrative structure (e.g. to regional and district Ministry of Health offices). Delegation involves a shift of authority and responsibility from centre to semi-autonomous agencies (e.g. autonomous hospitals; separate regulatory commission or accreditation commission). Finally, devolution shifts responsibility and authority from central offices of the Ministry of Health to separate administrative structures within the public administration (e.g. local and provincial governments, and municipalities). Within the three models there are a wide range of variants,Citation5 and although there are common components and goals, there are no blueprints for the exact form decentralisation should take.

To assess the impact of decentralisation on sexual and reproductive health services in Ghana this study addressed the following questions:

Do coherent, streamlined policies exist on the aims, organisation and management structures of the decentralised system and of sexual and reproductive health programmes within it?

Do clear, workable and equitable financial and resource allocation arrangements for sexual and reproductive health services exist within the decentralised system?

Are logistic and supply flows for sexual and reproductive health services within the decentralised system clear, efficient and sufficient?

What are the human resource arrangements and implications for sexual and reproductive health services within the decentralised system?

How far do inter-organisational linkages occur under decentralisation? Do they benefit sexual and reproductive health services?

Policy, governance and organisation

Ghana's health sector has undergone two key policy changes in the last decade: first, decentralisation and more recently the increased co-ordination of donors through a sector-wide approach (SWAp). Ghana has developed a mixed model of decentralisation, which formally began in 1992 with a constitutional commitment to decentralisation of public administration. The new institutional structures and the roles and functions of the various national, regional and district agencies are defined in a number of legal instruments covering civil service reform, local government restructuring and health sector deconcentration. Citation6 Citation7 Citation8 Citation9 Citation10 Citation11 Citation12 There are some discrepancies between the policies, however.Citation13 The 1993 Local Government Act envisages the health sector as competing with other sectors for decentralised funds, held by the Ministry of Local Government at the district level. Under the 1997 Ghana Health Service Act, however, the Ministry of Health retains financial autonomy, and it seems likely that this latter situation will prevail.Citation12

The role of the centre remains strong, with the Ministry of Health retaining policymaking functions but contracting out service delivery to provider agencies: the Ghana Health Service (GHS), teaching hospitals and non-governmental providers (usually contracted through the GHS).Citation14 Regional and district health management teams and regional hospitals have the status of Budget Management Centres, who sign performance contracts with the GHS. The regional management teams were intended to mediate communications between the national and local level, but their exact role and functions remain unclear. There are functioning district health management teams in each of the 110 districts, and most have sub-district health management teams, whose capacity is mixed. Despite the deconcentration of budget flows, the central Ministry of Health retains control over staff pay and recruitment, budgetary allocations and planning specifications. Although the effect of these changes on the functioning of programmes remains to be clarified, programmes remain strongly defined within the system.

Sexual and reproductive health within the decentralised system

Ghana, like many countries, has a long tradition of strong donor support for distinct family planning (FP), maternal and child health (MCH) and sexual health programmes (including HIV/AIDS), which comprise “sexual and reproductive health care” in large part. Traditionally, donors supported independent and parallel organisational and financing structures for each of these components. Under decentralisation and SWAps, however, these previously disparate programmes have become more streamlined, as donors have pooled and co-ordinated their funding. While many of these donors (notably USAID and the UN agencies) retain their priority areas for support, their contributions and their programme activities are far more co-ordinated. The attempt to bring together these programmes is exemplified in the national Reproductive Health Policy and Standards (1996) and its attendant Service Policy, Standards and Protocols, which form an overarching policy framework. A range of policy documents and manuals that pre-date the Protocols were still being used as more detailed, specialist documentsCitation15 Citation16 in 1996–98 by reproductive health staff in the Upper East Region. Since then, training has taken place in all districts on the use of the overarching Protocols, and it is expected that these will become the main reference documents.

Nevertheless, at the national level there remains some segregation of structures and responsibility. The Maternal, Child Health and Family Planning Unit (MCH–FP) Unit is responsible for MCH–FP and sexual health activities, while the National AIDS Control Programme in the Disease Control Unit is responsible for STI/HIV/AIDS activities—although STI treatment comes under the Institutional Care Division, as do midwives, since both of these staff types are considered to be “clinical”. These separate organisational structures have ostensibly been retained nationally to ensure the visibility of specialist policies and standards (particularly to donors). At regional and district level, the civil service reforms have only partially succeeded in unifying the programmes at regional and district management levels. Public health nurses are responsible for MCH–FP services, among others, while specialist HIV/STI officers co-ordinate these activities, although there is greater “team-work” between different staff at the regional and, particularly, district management levels. At the implementation level the two areas of activity are becoming more integrated, although personnel and supervisory structures are constrained by the continuing strong direction from programme and unit headquarters. The Protocols for implementing reproductive health aim to streamline activities as far as possible, for example, the protocols for managing sexually transmitted diseases are the same in the MCH–FP Unit's documents and the STI Unit's documents. Training in the different units also utilises the same Protocols. There is considerable co-ordination between the national MCH–FP Unit and the National AIDS Control Programme, but some difficulties remain on the ground regarding how integrated delivery of services is reported back to the different Units and Programmes at national level.

Finance and resource allocation

Health sector funding flows in Ghana have been subject to both deconcentration and sector-wide streamlining, resulting in a range of parallel financing and budget disbursal arrangements. Donors who are part of the new sector-wide approach (SWAp) channel their funds through the “Health Fund”. Donors who remain outside (notably, USAID and the UN agencies) retain earmarked funding flows, which are disbursed separately as “Earmarked Development Partner Funds”, and require separate reporting mechanisms at regional and district levels.Citation14 Nevertheless, the earmarked funds still support Government policies and form part of the Government's consolidated health budget.

Considerable progress has been made in deconcentrating health budgets. Financial allocations now go directly to the districts from central government, improving disbursement times.Citation14 The budget approval process, however, remains cumbersome, requiring all district and regional budget plans to be drawn up according to national guidelines and approved against nationally-set ceilings and priorities. This can delay disbursements, e.g. Upper East regional health management team members reported delays of up to six months in receiving approved budget estimates, with negative effects on planning and implementation.

Technically, district and regional health management teams are supposed to have some flexibility in decision-making about sexual and reproductive health care resource allocations and activities at local levels, based on the expressed needs of facility staff and the District and Regional MCH and STI officers. Reality is somewhat different:

“…by the time money passes through the MoH, from the region, through the regional director, the district director, by the time it gets to the village, we know how it is all to be spent.” (Interview, Assemblyman, Upper East Region)

Funding under the SWAp

Health Fund budgets to district level come earmarked not by service allocations but by salaries, capital expenditure, administration and service-related expenses. Districts cannot re-allocate these budget lines, although transfers may be made within a budget line and greater flexibility is envisaged for the future. Each line comes through a different disbursement mechanism, so their arrival is not co-ordinated, creating difficulties for district planners and managers.Citation14 Although service-specific earmarking no longer occurs, districts are expected to meet national priority targets. Reproductive health indicators are included in the 22 national indicators agreed by donors and the MoH under the SWAp. Thus, each district is now required to report on antenatal coverage, family planning coverage, post-natal care and maternal health and death audits.

Previously, programme activities at district level relied heavily on vertical donor funding that came earmarked for STI/HIV or MCH–FP activities. As these have declined, questions have been raised over adequate funding for sexual and reproductive health, especially in poorer, rural regions, where issues of access to clean water and sufficient food are of paramount concern and other national priority areas become sidelined:

“[Money] used to come purely from donors and NGOs but the whole of this year we've received nothing… There is no money to AIDS or even disease control; it comes to the directorate, and for running costs, vehicles, and maybe for health education… So far as I'm concerned no money comes to me for STD/HIV.” (Interview, Regional officer)

Earmarked funds

In this environment, the earmarked funds (which may be either government or donor managed) that still exist give a significant boost to sexual and reproductive health services within the decentralised system, as they tend to focus on specific programme activities such as training or mobilisation for vertical activities. According to one regional administrator, these funds are “normally addressed to the regional director of health services, and the accompanying letter will specify what the money should be used for and how returns will be submitted to headquarters” (Interview, 1997). Nevertheless, despite the “strings” attached to these funds, district officers maintain some leeway and managers talk of “ways and means” by which they can shift programme funds at the implementation level, “providing the main thrust of the project is achieved” (Interviews, Regional Health Management Team members, Upper East Region).

The major drawback of earmarked funds is that they frequently fail to be connected to the planning and activity schedules of regional and district staff. In particular, donor funding was said to come in bits to various programmes throughout the year, making it very difficult to implement ongoing integrated programmes.

“Every group wants to have their own constituency… You have HIV/AIDS people who have drawn up the plan of action, who have funds from different donors for particular activities… and the same for MCH–FP. And what happens then is that from nowhere, they [District Health Management Teams] get a cheque for two million cedis—could you please do training on counselling and so on and we will send you a resource person. And the next week they get another amount of money—can you do TBA refresher training, or can you do something on baby-friendly hospitals or breast-feeding—very disruptive for them…” (Interview, senior official, Ministry of Health, Accra)

Local funding sources

The non-central sources of finance are limited at regional and district levels. Some non-SWAp donors and international NGOs continue to fund directly to regional and district levels, although central government discourages this.Citation15 Donor monies and support may also come into the region in kind (as contraceptives, test-kits, vehicles and so on). Districts are also permitted to levy fees and local taxes (e.g. on market stalls, registration and operation of druggists and private clinics) to use for locally defined priorities.Citation7 Citation8 Citation17 More significant for health are the user fees that account for 20% of district Ministry of Health spending in total and are included in the health sector budgets for planning purposes. In poor regions, although income from user fees is small, it does enhance decentralised decision-making since it remains under district and facility jurisdiction. Fees go into revolving drugs funds and are charged for consultations, theatre and equipment. The scale of fees and which items should be charged for is currently undergoing review after internal research suggested widespread abuse of the system through charging of illegal fees.Citation15 The District Assembly (DA) common fund (i.e. extra finances from central government for local priority spending) also represents a source of funding for health. District Health Management Teams must apply for this on a competitive basis with other sector ministries and success in receiving an allocation depends on priority setting and individual lobbying ability:

“This common fund is meant for priority projects in the district. So if it happens that a health project is seen to be a priority project within the DA's overall plan, then they will finance it from this common fund… So if the district director of health services is able to make his case very clear, and win the confidence of the DA members, then automatically they will assist him with whatever plans that he has there.” (Interview, officer, Upper East Region)

Logistic and supply flows within a centralised procurement system

Effective sexual and reproductive health services depend on reliable contraceptive and drug supplies. Currently logistics and supply procurement run through two parallel systems: government procurement through centralised Central Medical Stores, and donor procurement, notably of family planning supplies and equipment. Under the Government's new “Partnership Outsourcing” scheme these parallel arrangements are intended to be unified over a five-year period as part of wider reforms in public procurement and financial management.Citation14 The Ministry of Health will select a procurement agent through competitive tendering but will retain overall control of the process. Procurement plans will be developed by district and regional management teams and supplies will flow through a strengthened Central Medical Stores.

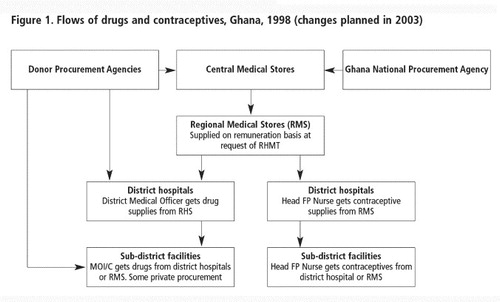

shows the donor and government procurement systems for contraceptive and drug flows. The relative reliability of contraceptive availability is due to reliable donor supplies. Contraceptives procured by USAID and UNFPA are delivered to the regions quarterly from the Central Medical Stores in Greater Accra. They have their own vertical delivery and accountability structures, with Family Planning Unit heads in each region and at each facility being responsible for procuring contraceptives and collecting monies for them, separate from other medical supplies and drugs. Reagents for STI and HIV tests also come through Central Medical Stores, and again are often from donors. It is as yet unclear how the new procurement system will affect these flows.

Budgets to buy supplies from Central Medical Stores are allocated from central Ministry of Health according to estimates from district and regional health management teams, based on aggregated reported facility-level needs. Currently, in the Upper East Region, district and regional staff report generally good contraceptive supplies, despite occasional shortages and “fluctuations”.Citation17 There are, however, major issues around the expense of many drugs, both for health management teams to buy for the regional stores, and for patients who must pay for them.

“The major problem is the availability of cash… At first, we were sold drugs on credit… But the patients couldn't pay, so now we have to pay before we get the drugs.” (Interview, Dispensing Technician, Health Centre, Bolgatanga)

During the study period, regional health management teams procured supplies from Central Medical Stores to stock regional medical stores, and the districts collected the supplies they needed from the regional stores on a regular basis. Facility-level MCH–STI officers were, in turn, responsible for ensuring adequate supplies at their facility (Interviews, regional, district and facility key informants). From June 2003, however, district-level procurement is set to be removed, with contraceptives and drugs flowing from Central Medical Stores first to regional levels and then direct to health facilities. This is expected to reduce the cost of drugs to the facilities, since drugs bought from Central and Regional medical stores are cheaper than those procured at district level, due to economies of scale from bulk-buying. It is also intended to improve the time-flow, although the time and transport costs may be increased for facilities, who will now have to collect supplies from the regional stores rather than district hospitals. Under the current system, regions, districts and facilities must bear the costs of transportation; in poor or rural areas far from the capital, this can be a major impediment to regular supplies. The new arrangements intend that each region will be allocated a vehicle to distribute supplies to each facility, but this has yet to be implemented.

There are some district-level sources of funding which could support procurement, but these may be insufficient or inappropriately used. For example, one District director said that shortages and delays in drug supplies were “the result of the district locking up its revolving funds by buying drugs which aren't used… without careful thought about disease priorities… The cash and carry system means we buy as and when.” (Interview, District director). He believed meticulous planning should avoid this, underlining the importance of district management and planning skills.

Human resources management and training

The reform of human resource management has been a smaller and less radical part of the national civil and health sector reforms.Citation18 The appointment, promotion, sacking and retirement of reproductive health staff at all levels within the health sector were, until recently, undertaken by the Head of the Civil Service; however, this is increasingly becoming the responsibility of the Ghana Health Service, with some delegation to the regions. Where staff are seconded from GHS to mission or NGO facilities, they are subject to GHS rules and regulations. However, contracted missions and NGOs may also privately advertise for, employ and pay their own reproductive health staff and are allowed to top-up salaries and offer other incentives, such as good housing or a vehicle (Interviews, Ministry of Health, Christian Health Association of Ghana, Anglican and Presbyterian mission representatives at national, regional and district levels). Districts and regions may also offer in-kind incentives, such as housing and vehicles, but may not increase salaries. However, the poorest regions, who most need to offer incentives to attract and retain staff, have limited ability to do so.

Reproductive health staff who worked in deprived and rural districts of the Upper East Region frequently complained in interviews about poor working conditions and career prospects; there is a high turnover among them and many vacancies. Regional and district health management teams are well aware of the difficulties they face in trying to retain good staff. A regional report from the Upper East records that “the state of staff housing is deplorable… It is therefore needless to say that this is the more reason why qualified personnel are not attracted …”Citation19 Several districts in the Upper East Region were without resident district directors because people refused to move to districts where there were inadequate living conditions, communication facilities or schooling for children.Citation15

Career advancement opportunities, such as training, could be an incentive, but a number of problems emerged during the study period regarding sexual and reproductive health training programmes. The policy of the Ministry of Health is to train regional trainers, who then train service providers in their districts. For training in the use of new guidelines, such as the National Reproductive Health Protocols, this is what has occurred. Other specialist training initiatives, e.g. on syndromic management of STIs, may come from either Ministry of Health headquarters, donor or NGO agencies. Two sorts of problems were being experienced in the Upper East Region. First, senior staff were often selected for training as a perk, rather than lower-ranking staff who were supposed to be providing the service. Second, the frequent absence of senior staff at training sessions was resulting in great disruption of service provision.Citation15 Citation19

Furthermore, Upper East staff noted that training materials were not always left with regional staff to re-use, and follow-up was rarely undertaken. Although national level contact with the region is good—with twice-yearly meetings of senior (regional) health managers and with regional training teams—difficulties were encountered in practice. All training participants received manuals, but of the numerous training initiatives run by donors and central Ministry of Health during the study period, not one left behind a training manual or even a report for district and regional administrations to keep as resources for follow-up and reference. The one-off nature of much training also drew sharp criticism from District Directors:

“Training for training's sake is useless… If the trainers come back and ask questions—‘But we taught you this six months ago why isn't it being done?’, then people would sit up, but they just come once and don't return.” (Interview, District director, Upper East Region)

“In Accra there are funds for training so they do it … People come from Accra to Navrongo to train and then go back and that's the end of it… If they are not going to follow up they shouldn't come to Navrongo at all.” (Interview, District director, Upper East Region)

Decentralised inter-agency linkage

Decentralisation was intended to be accompanied by formal consolidation of communication networks between government sectors and other organisations, to facilitate and enrich health-related activities—something the ICPD also regarded as central to achieving its goals. At a national level some formal contractual arrangements exist between the GHS and providers under the umbrella Christian Health Association of Ghana. Certain other NGO partners are also recognised in the provision of family planning and sexual health care, but operational linkages and co-ordination of activities have been problematic. At regional and especially district levels, the cast of significant actors is relatively small and linkage between organisations and sectors does occur albeit on an ad hoc basis and dependent on personal contacts. True partnership, however, has not yet developed in terms of joint goals and objectives, planning, resource-sharing, service delivery or co-ordination.

Formal regional co-ordination mechanisms between the Ministry of Health and NGOs, and across sector ministries, are also limited. A number of regional level structures are supposed to have a co-ordinating role, to ensure that NGO and sector ministry inputs do not duplicate or overlap but complement each other. For example, the Ministry of Health is supposed to forward information to the National Council on Women and Development (NCWD), who in turn is supposed to co-ordinate district programmes concerned with women (Interview, Regional NCWD Director). In practice, links between health and municipal structures at the regional level seldom extend beyond courtesy calls (Personal observation, key informant interviews). Ineffectual regional co-ordination has led to situations where several missions are operating in the same village without realising it.

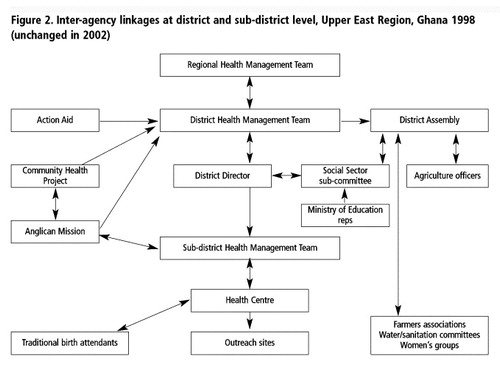

District-level relations between the Ministry of Health and NGOs, churches and local groups, are often well developed, on the other hand. Linkages between districts and sub-districts are also well functioning, because many district actors are also “big men” at sub-district levels of government. At these levels, the number of actors involved in health issues is much broader than at regional and national levels, and links between local, ministry, municipal, NGO and church groupings are often quite fluid. Many of these linkages are informal, with information being shared through personal contact. In the study district, a number of multi-agency initiatives were working on a variety of health issues, including one on maternal health, which was widely regarded as a local priority.

Some linkages between district health management teams and community members sitting on the locally elected District Assembly are ensured through the district director, who sits on the Assembly's social sector sub-committee, which meets quarterly. There are, however, no sexual/reproductive health-specific representatives at this level. Although the District Health Management Team does have a public health nurse responsible for reproductive health it is the district director who represents health concerns to the District Assembly. Unless the director sees reproductive health as a priority it is broader health issues (malnutrition, seasonal illnesses, infrastructure) that receive most attention. The District Assembly has resources that could be tapped by the Ministry of Health under the decentralisation policy, as noted earlier. But commitment may not translate into funds. Lip-service was paid by interviewed District Assembly members to improving local health services and building more clinics in their localities, but no funds had been allocated and one member of the Assembly's Health Committee observed:

“I doubt they have funds for these health issues. They feel they must say it to please the people.” (Interview, Health Committee member, Binaba)

Where district health management teams are led by committed and dynamic personalities much can be achieved. Some district health management teams in the Upper East Region have actively co-opted members from a number of key NGOs working in the area, as well as representatives from other sectors, like Agriculture and Education. They meet monthly and have devised innovative, joint reproductive health-related activities, such as sex education quizzes for schoolchildren, football tournaments for out-of-school youth with safe sex T-shirts and condoms as prizes, and distribution and promotion of condoms by agricultural extension workers.Citation15 Citation19 The links between a range of stakeholders are shown in , as an example of the type of multisector networking that can be achieved under decentralisation and in the spirit of ICPD. The key issue at this level is having reproductive health advocates who are strong enough to keep reproductive health on the agenda vis-à-vis other primary health care needs, which compete as priorities.

Discussion

Decentralisation is about changing organisational, financial and managerial arrangements and responsibilities within the health system. The ICPD also envisaged the expansion and enhancement of the concept and provision of sexual and reproductive health services. As a major component of primary health care at district level, sexual and reproductive health services are central in the changes wrought by decentralisation.

In most countries, decentralisation has been undertaken as part of a much wider-reaching package of civil service and public administration reforms and is never politically neutral.Citation20 The changing roles of the centre vis-à-vis the periphery lies at the core, with considerable national and local political territory at stake. Central governments in many countries have been slow to relinquish power, including in Ghana, where the Government took a deliberate decision to go down the path of deconcentration rather than full devolution. Even in the deconcentration model, there have been widespread concerns in a number of countries regarding the extent of capacity-building needed for regional and district administrations to carry out supervision, training and planning.Citation20 Citation21 This has also been a concern in Ghana, but more obvious have been uncertainties about the nature of the linkages between the different actors in the decentralised system, both vertically (i.e. between central provider agencies, Budget Management Centres and health facilities) and horizontally (i.e. between Ministry of Health actors and other ministries).Citation18

Local-level streamlining and integration are emphasised in this new system. But vertical linkages between reproductive health programmes, units and bodies at national level, within deconcentrated resource allocation, management and financing structures, needs further clarity. At a policy level, it would seem that there is still a need to co-ordinate national and deconcentrated organisation of reproductive health care further, to allow managers to focus on service delivery issues rather than duplicate administrative reporting. There is also a need for policies that clarify Ministry of Health and local government links, in order to further community awareness about sexual and reproductive health issues and to increase the democratic accountability of sexual and reproductive health and other health services.

The deconcentrated Ministry of Health structure was supposed to enable better links with community representatives on elected District Assemblies—and therefore greater accountability—but the slower decentralisation of the Ministry of Local Government has impeded this. Furthermore, the nature of the linkages between regional and district health management teams (who are centrally appointed), District Assemblies (who are elected) and other community organisations remains unclear. The uneven speed of decentralisation and the different forms it has taken in different ministries are issues that have also been raised in other countries.

Decentralisation of financing is particularly political, and Ghana is no exception. While the handling of finances is in the process of decentralising, decisions on spending are not, and funding flexibility is still centrally controlled. In many ways the consequences of this for sexual and reproductive health are positive. Several countries have reported problems with decentralised spending, with poorer regions unable to meet priority targets or reproductive health not being made a priority for district spending, resulting in lack of drugs and equipment for reproductive health services.Citation1 Citation22 Citation23 Although a range of avenues for financing of reproductive health programmes exists in Ghana, harnessing them requires active advocacy and imaginative employment of existing resources, rather than the more passive reliance on vertical donor funding for specific activities. For example, the common fund at district level could become a potentially important extra source of funding for reproductive health, as could local tax allocations, providing a strong case can be made vis-à-vis other district priorities. Where advocacy skills do not exist, or sexual and reproductive health is not considered a local priority, or communities are too poor to generate sufficient extra funds to support these services, central earmarking of funds may help to ensure adequate financing of reproductive health components. This is most clearly manifest in the continued reliability of contraceptive supplies, which are still supported by earmarked donor funding.

Commodity flows in Ghana are expected to improve with the introduction of new procurement and disbursal procedures that remove the district as a bureaucratic layer. While retaining centralised procurement of sexual and reproductive health commodities ensures that the cost to facilities of drug supplies is kept at a minimum, the issue of transport costs from regional stores to facilities has yet to be resolved. For poorer regions and facilities unable to afford all supplies they need, some kind of national “top-up” allowance may be necessary, as has been introduced in Brazil,Citation22 since decentralised resources (user fees, local taxes) are not sufficient to ensure the ability to pay for constant supplies.

In many countries' decentralisation policies the management of human resources has featured only slightly.Citation20 Unlike many decentralising countries, Ghana has not de-linked its health sector staff to the control of the Ministry of Local Government; instead, the Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Service retain jurisdiction over all areas of human resource management. This avoids problems associated with loss of career paths and specialist advancement experienced in some countries. At district level, however, especially in poor and rural areas, Ghana has experienced problems common to many other countries in terms of retention of staff because of lack of career prospects or training opportunities in rural and poorer areas.

Though these are generic health sector problems, sexual and reproductive health staff make up a large proportion of primary health care staff, especially in rural areas. Work is often more attractive in the private sector or with missions and NGOs, who may offer top-up payments, better working conditions and career prospects. There is mixed evidence as to the efficacy of decentralising recruitment and payment of human resources, particularly where decentralised management capacity is weak.Citation20 In Ghana, where human resource management remains highly centralised, nationally allocated incentives for key reproductive health staff (e.g. midwives and public-health trained family planning nurses) in deprived areas could be given serious consideration. Human resource capacity could be strengthened if national and donor trainers were required to leave behind the resources they use for district and regional personnel. This would also facilitate decentralised follow-up of training by district and regional management. Also beneficial would be allowing district and regional health management teams the authority to co-ordinate training initiatives more locally, to minimise disruption of service.

Vision and commitment to inter-sectoral linkage are limited in many countries,Citation1 Citation21 and links between government structures and communities, NGOs and other agencies are mixed.Citation21 Citation23 The Ghanaian experience has shown that district-level networks can offer valuable opportunities for creative, innovative and locally-responsive initiatives for sexual and reproductive health, since district Ministry of Health personnel usually have good (often personal) links with mission and NGO workers. Links between district health and local government officials, however, remain weak, and advocacy needs strengthening if sexual and reproductive health issues are to be seen as a priority at community level. Formal linking mechanisms may need to be established to secure sustainable multi-organisational and multi-sector initiatives at district level, although evidence is lacking as to the best ways to ensure these are functional.

It is hard to assess the current effect of reforms in Ghana (or elsewhere), since there are no published data measuring the impact of sectoral changes on sexual and reproductive health indicators. This is probably in part because of the difficulties in attributing direct causality, even though there is a general assumption that improved service quality, coverage and functioning will lead to better health indicators. A comparison of selected reproductive health indicators for Ghana in 1993,Citation24 the year that decentralisation began, and 1998–99,Citation25 the last year for which data are available, shows that there has been little or no improvement in the contraceptive prevalence rate (10% vs. 13%), antenatal coverage of live births (86% vs. 89%), or supervised deliveries (42% vs. 43%). However, it may be too early to see any population-level impact from the reforms. The most important negative change has been an increase in reported cases of HIV infection and AIDS.Citation26 Citation27

Conclusions and considerations for the future

This paper has identified a number of issues and concerns which sexual and reproductive health advocates and policymakers in Ghana might want to consider:

Policies and guidelines on the aims, organisation and management of sexual and reproductive health services within the decentralised system are still fragmented. Clarity is needed on how different national sexual and reproductive health bodies relate to each other and to regional and district health authorities.

Financial flows to districts have improved considerably with deconcentration of budgets. Decision-making remains centralised, and this may be necessary to safeguard district sexual and reproductive health activities, through national earmarking of funding for these services. Additionally, advocacy for sexual and reproductive health needs strengthening at district level to help to secure extra funds.

Logistic and supply flows for sexual and reproductive health commodities also display a mix of centralisation and decentralisation: procurement is centralised and non-donor supported commodities like STI drugs can be expensive for poorer districts. Districts must bear responsibility for transportation and payment for drugs; hence, poor districts may need national “top-up” funds to ensure adequate and regular supplies.

Human resource arrangements are also still centralised. This means poor and rural districts are unable to offer adequate working conditions and cannot retain staff. A national incentive scheme could be considered, or a decentralisation of responsibility to allow districts to offer incentives—though again, poor districts may need national help.

Inter-organisational linkages often occur at district level on an ad hoc basis. The extent to which this benefits sexual and reproductive health care depends on the personalities and commitment of local sexual and reproductive health advocates (whether public health or NGO staff). The addition of more formal links might ensure ongoing linkages are maintained.

The development of formal mechanisms for priority setting and advocacy could also help to secure benefits for sexual and reproductive health in the context of the full range of health needs.Citation28

Given the increase in reported HIV/AIDS cases, serious consideration must be given to the most effective way to strengthen the National AIDS Control Programme as a multi-sectoral, priority programme, e.g. with earmarked funding and resources, as has been done in South Africa, and at the same time consider how best to involve the MCH–FP Unit and the Institutional Care Division who are responsible for STI treatment, within the decentralised system.

Decentralisation offers a number of opportunities for promoting the post-Cairo vision of multisectoral, more accountable and locally-oriented provision of sexual and reproductive health services. It also raises the need for strong advocates for sexual and reproductive health services at the district and sub-district levels and consideration of how poorer regions and districts can be supported to ensure a secure and equitable provision of services. Decentralisation will continue, whatever the views of the sexual and reproductive health community. The challenge is to work with the changes and seek to influence them to secure maximum benefit to improve sexual and reproductive health.

Acknowledgements

The bulk of this research was done as part of PhD fieldwork undertaken at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and supervised by Prof Gill Walt. The PhD work was funded by a three-year ESRC studentship; the follow-up trips were made under the auspices of a DFID-funded Knowledge Programme on Sexual and Reproductive Health. Thanks are due to Dr Sam Adjei (Executive Director, Ghana Health Service) for providing introductions, a base and invaluable advice. Thanks also to all the Ministry of Health staff at national level, especially Dr Odoi-Agyarko and her staff in the MCH–FP Unit in Accra, and in the Upper East Region, particularly in the Regional Health Administration and Bawku-West sub-district. Special thanks to Dr Amankuah, Upper East Regional Director of Health, who generously gave the use of Ministry vehicles and our local driver, Mustapha, whose geographical knowledge was invaluable. A big thank-you to all clinic and hospital staff who gave their time to speak to us and who work with compassion against the odds. Finally, thanks to Nancy Gerein, Henrietta Odoi-Agyarko and Sam Adjei for detailed comments on previous drafts.

References

- M Lubben, SH Mayhew, C Collins. Reproductive health and health systems change: establishing a framework for dialogue. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(8): 2002; 667–673.

- SH Mayhew. Integration of STI services into FP/MCH services: health service and social contexts in rural Ghana. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 112–124.

- SH Mayhew, L Lush, J Cleland. Implementing the integration of component services for reproductive health. Studies in Family Planning. 31(2): 2000; 151–162.

- D Rondinelli. Government decentralisation in comparative perspective: theory and practice in developing countries. International Review of Administrative Science. 7(2): 1981; 133–145.

- Bossert T, Beauvais J, Bowser D. Decentralisation of Health Systems: Preliminary Review of Four Country Case Studies. Major Applied Research 6, Technical Report No 1. Bethesda MD: Partnership for Health Reform Project, Abt Associates, 2000.

- Government of Ghana. PNDC Law 207 on rights to local government. Accra, Ghana, 1992.

- Government of Ghana. The Civil Service Law. PNDC Law 327. Accra, 1993.

- Government of Ghana. Local Government Act, Act 462. Accra, 1993.

- Government of Ghana. National Development Planning Commission Act, Act 479. Accra, 1994.

- Government of Ghana. National Development Planning (System) Act, Act 480. Accra, 1994.

- Government of Ghana. Local Government (Urban, Zonal and Town Councils and Unit Committees Establishment) Instrument 1994 (L-1 1589).

- Government of Ghana. Ghana Health Service and Teaching Hospitals Act, Act 525. Accra, 1996.

- Cassels A, Janovsky K. Reform of the health sector in Ghana and Zambia: commonalties and contrasts. 1996. (Unpublished).

- Ghana Ministry of Health. Common Management Arrangements II: For the Implementation of the Second Health Sector Five-Year Programme of Work 2002–2006. Accra, January 2002.

- Mayhew SH. Health care in context, policy into practice: a policy analysis of integrating STD/HIV and MCH/FP services in Ghana. University of London, PhD dissertation. London, 1998–99.

- L Lush, J Cleland, G Walt. Integrating reproductive health: myth and ideology. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(9): 1999; 771–777.

- Ghana Ministry of Local Government. Bawku West and Bolgatanga District Assembly Fee Fixing Resolutions. Bolgatanga, 1997.

- Dovlo D. Comment. In: Kolehmainen-Aitken R-L. Decentralisation and Human Resources: Implications and Impact. Round Table discussion paper, Management Sciences for Health, Boston (undated).

- Ghana Ministry of Health. Upper East Region Annual Report, Regional Health Management Team. Bolgatanga, 1996.

- Y Wang, C Collins, S Tang. Health systems decentralisation and human resources management in low and middle income countries. Public Administration and Development. 22: 2002; 429–453.

- A Jeppsson, SA Okuonzi. Vertical or holistic decentralisation of the health sector? Experiences in Zambia and Uganda. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 15: 2000; 273–289.

- C Collins, J Araujo, J Barboda. Decentralising the health sector: issues in Brazil. Health Policy. 52: 2000; 113–127.

- A Jeppsson. SWAp dynamics in a decentralised context: experiences from Uganda. Social Science and Medicine. 55: 2002; 2053–2060.

- Ghana Statistical Service/Macro International, Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 1993, Accra.

- Ghana Statistical Service/Macro International, Ghana Demographic and Health Survey, 1998, Accra.

- Ghana Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Programme, AIDS Surveillance Report 1996, Accra.

- Ghana Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Programme, AIDS Surveillance Report 1999, Accra.

- LJ Reichenbach. The politics of priority setting for reproductive health: breast and cervical cancer in Ghana. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(20): 2002; 47–58.