Abstract

Universal access to comprehensive reproductive health services, integrated into a well-functioning health system, remains an unfulfilled objective in many countries. In 2000–2001, in Tanzania, in-depth interviews were conducted with central level stakeholders and focus group discussions held with health management staff in three regional and nine district health offices, to assess progress in the integration of reproductive health services. Respondents at all levels reported stalled integration and lack of synchronisation in the planning and management of key services. This was attributed to fear of loss of power and resources among national level managers, uncertainty as to continuation of donor support and lack of linkages with the Health Sector Reform Secretariat. Among reproductive health programmes, sexually transmitted infection (STI) control alone retained its vertical planning, management and implementation structures. District-level respondents expressed frustration in their efforts to coordinate STI service delivery with other, more integrated programmes. They reported contradictory directives and poor communication channels with higher levels of the Ministry of Health; lack of technical skills at district level to undertake supervision of integrated services; low morale due to low salaries; and lack of district autonomy in decision-making. Integration requires a coherent policy environment. The uncoordinated and conflicting agendas of donors, on whom Tanzania is too heavily reliant, is a major obstacle.

Résumé

Peu de pays garantissent un accès universel à des services complets de santé génésique, intégrés dans un bon système de santé. En 2000-2001, on a mené en Tanzanie des entretiens avec des responsables du niveau central et des discussions de groupes avec du personnel de gestion dans trois bureaux régionaux et neuf bureaux de district, pour évaluer les progrès de l’intégration des services de santé génésique. Les répondants à tous les niveaux ont noté un blocage de l’intégration et un manque de synchronisation dans la planification et la gestion de services clés. Ils l’attribuaient à la crainte des administrateurs du niveau national de perdre des pouvoirs et des ressources, aux incertitudes quant à la poursuite de l’appui des donateurs et au manque de liens avec le Secrétariat de la réforme du secteur sanitaire. Seul, parmi les programmes de santé génésique, le programme de lutte contre les IST conservait complètement ses structures verticales de planification, de gestion et d’exécution. Les répondants au niveau du district ont cité des difficultés pour coordonner les services d’IST avec d’autres programmes plus intégrés, dues à des directives contradictoires et à des réseaux médiocres de communication avec les niveaux supérieurs du Ministère de la santé, aux compétences techniques insuffisantes pour mener une supervision intégrée, au mauvais moral dû aux bas salaires, et au manque d’autonomie de décision des districts. L’intégration exige un climat politique cohérent. Les priorités non coordonnées et opposées des donateurs, dont la Tanzanie est trop dépendante, sont un obstacle majeur.

Resumen

El acceso universal a servicios completos de salud reproductiva integrados en un sistema de salud operante sigue siendo un objetivo sin alcanzar en muchos paises. Para evaluar avances de la integración de los servicios de salud reproductiva en Tanzania, en 2000-2001 se realizaron entrevistas en profundidad con las partes interesadas a nivel central, y grupos focales con el personal de gestión en salud en tres servicios de salud regionales y nueve servicios de distrito. Se reportó un estancamiento en la integración a todo nivel y una falta de sincronización en la planificación y gestión de servicios claves. Se atribuyó la situación al temor entre los administradores a nivel nacional a perder poder y recursos, a inseguridad con respecto a la continuación de apoyo financiero, y a la falta de vı́nculos con el Secretariado de la Reforma del Sector Salud. El único programa de salud reproductiva que mantuvo completamente sus estructuras de planificación, gestión e implementación verticales fue el programa de control de las infecciones transmitidas sexualmente (ITS). A nivel de distrito se expresó frustración con los esfuerzos por coordinar la entrega de servicios de ITS con otros programas más integrados. Se reportaron directivas contradictorias y canales de comunicación deficientes con los niveles superiores del Ministerio de Salud; falta de capacidad técnica para emprender la supervisión de servicios integrados; bajo moral debido a salarios bajos; y falta de autonomia para la toma de decisiones a nivel de distrito. La integración requiere un ambiente politico coherente. La falta de coordinación entre las agendas de los donantes, y conflicto entre ellos, son un obstáculo mayor, ya que Tanzania depende tanto de ellos.

A central theme of the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) was that the provision of comprehensive reproductive health programmes would be facilitated through integrating service delivery.Citation1 The rationale for integration is two-fold: to make reproductive health services more accessible and convenient to users, and to increase service efficiency by sharing facilities and personnel, and reducing duplication in administration and service delivery.Citation2 Citation3 Cardinal features of health sector reforms in sub-Saharan Africa over the last 15 years have been the deconcentration of administration and service implementation, and the devolution of decision-making powers to the district level. Efforts to reform how the health sector is organised, through decentralising planning, management and decision-making “down the administrative hierarchy”,Citation4 preceded the ICPD by several years.Citation5

One of the objectives of health sector reform, which corresponds with the ICPD agenda, has been to “improve service organisation by reducing duplication of service provision, enhancing the effectiveness of care delivered at each level and overcoming access and communication problems”.Citation4 Health sector reform provides the systems context for the delivery of reproductive health services in many African countries. Where resources and decision-making are decentralised to political structures at the district level, which is the reform model being implemented in Tanzania,Citation6 it should deliver the benefits of integration, including intersectoral HIV/AIDS control.Citation7 However, more than 15 years into health sector reform and almost a decade after the ICPD, universal access to comprehensive reproductive health services, integrated within a well-functioning health system, remains in many countries an unfulfilled objective.Citation1

Selective and comprehensive approaches to delivering primary health care (PHC) were hotly debated during the 1980s,Citation8 with the former seen as donor-driven approaches, which resulted in programmes having separate and parallel systems of funding, planning, management and implementation.Citation5 The influence of donors, whose control over resources can distort or impede policy implementation, has been an obstacle to integrating reproductive health services, notably to incorporating HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) control into comprehensive reproductive health programmes.Citation9 The result in several sub-Saharan African countries has been piecemeal integration and uncertainty around who should be responsible for supervision and quality assurance of services.Citation9 Citation10 Citation11 Lubben et al attribute contradictory policies and the stalling of integration processes to a lack of dialogue between health sector reform and reproductive health policy groups, despite widespread acknowledgement of the need for a holistic approach to reproductive health.Citation9

How have health workers and managers at the district level been responding, as they have attempted to work within a discordant policy environment? What have the effects of central level directives and management processes been on district-level efforts to provide integrated reproductive health services? This paper is based on a multi-level analysis conducted in Tanzania in 2000–2001 to assess progress and identify obstacles towards ensuring that comprehensive, quality reproductive health services were being provided at the primary health care level. It reports the views of district and central level stakeholders on what they understood by integration and how to achieve programme co-ordination in a reforming health sector. STI control is used as a tracer, so as to identify the obstacles at different levels of the health system to integrating it within an otherwise decentralised reproductive health programme. Problems of low capacity and morale at the district level are reported. A subsequent paper will report on service outcomes.

The health sector in Tanzania

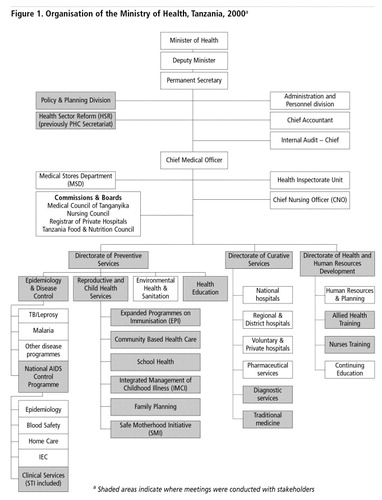

In 1995, one year after the ICPD, Tanzania established a new Reproductive and Child Health Service (RCHS) section, located in the Preventive Health Services Directorate of the Ministry of Health (MoH). Its purpose was to ensure that the reproductive health needs of Tanzanians were addressed in a comprehensive way. During 2000–2001, RCHS included sub-units responsible for Family Planning, School Health, Community-Based Health Care, Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses, and the Safe Motherhood Initiative (). Epidemiology and Disease Control was a separate section, under Preventive Health, housing disease control programmes, including the TB/Leprosy and Malaria Units and the National AIDS Control Programme (NACP). The National AIDS Control Programme included five technical sub-units responsible for: Clinical Services (including STIs), Home-based AIDS Care, Information Education and Communication, Blood Safety and Epidemiology.

Policy and Planning is a division of the MoH directly accountable to the Permanent Secretary, the Deputy Minister and the Minister of Health. The Health Sector Reform Secretariat (HSR) is a unit under Policy and Planning, responsible for driving implementation of the reforms, including integration of vertical programmes. HSR is essentially an independent structure within the MoH and does not have direct links with the technical implementing sections of the MoH, including those that come under Preventive Health Services. This has implications for coherent policy implementation and directives to lower levels of the health system, as emerged in the study findings. In 2001, a decision was taken to transfer the STI sub-unit to the RCHS, in line with efforts to integrate vertical programmes.Citation12 The transfer had not yet taken place by the end of the study period.

Methodology

The methodology consisted of interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs) and document review. In-depth interviews were conducted in English with 52 key informants at the central level: MoH policymakers and programme managers, mainly those with some responsibility for reproductive health services (see ); and representatives of multilateral agencies, bilateral donor and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Tape-recorded FGDs were conducted with each of three Regional Health Management Teams and each of nine District Health Management Teams (DHMTs). Regions were purposively selected where STI control programmes had been in place for six, four and two years respectively, in line with the objective of the larger study to evaluate STI service outcomes. This selection enabled the process of reproductive health service integration to be evaluated in districts at different stages of STI control implementation. Three districts were randomly selected within each region. The interview and FGD guides covered issues of procurement and distribution of drugs and other health products; supervision of health workers, decision-making and team work; the influence of health sector reform and local government reform on their activities; and the impact of decentralisation on autonomy and power.

FGDs were attended by 8–12 participants each. In each case, these included Reproductive and Child Health, HIV/AIDS and STI Co-ordinators, and District or Regional Medical Officers, depending on the level. Additional participants included pharmacists, Cold Chain Coordinators, TB/Leprosy Coordinators and other District or Regional Health Management Team members. During the discussions, participants were encouraged to share the work difficulties they faced on a daily basis. Other discussion items were to do with funding, planning for and implementing sexual and reproductive health services (particularly safe motherhood, family planning, STI and HIV/AIDS services), handling directives from higher levels and providing technical support to health delivery staff. FGD respondents were invited to speak in whichever language they were most comfortable, either English or Kiswahili. Audio-recordings were where necessary translated, transcribed and analysed using the Nudist qualitative research software package.

The findings are presented under the following themes: understanding what is meant by integration; co-ordination of activities and responsibilities; integration of STI control into reproductive health programmes; fear, power and autonomy; and human resource issues.

Understanding integration

The policy of the MoH in Tanzania is to promote integration:

“The MoH [appreciates] the desirability of integrating vertical programmes which were hitherto controlled either from the centre or directly by donors. This does not undermine the integrity of vertical programmes as most—EDP [Essential Drugs Programme], EPI [Expanded Programme on Immunizations] and malaria for example—have had a very significant role, but which now need to be incorporated into PHC management.” Citation13

Among respondents, there were some common understandings of the overall purpose of integration, which was to achieve the smooth co-ordinated programming and delivery of key components of reproductive health services to men and women. However, definitions of integration and understandings of how to implement it varied widely, often according to programme perspective or role within the health system. Some saw it as integration at the point of service delivery:

“Here is an example: counselling and condoms, a client gets both of these in one room—that is integration.” (Safe Motherhood Initiative, RCHS, MoH)

“Integration… means that sexual and reproductive health should be part and parcel… If we talk about malaria, we will also talk about STIs, reproductive health and HIV. The patient comes to the health unit, we address all these issues.” (Regional Administration and Local Government)

Others emphasised integration of management or logistical functions:

“Integration is integration of the logistical aspects. We… try to avoid duplication and wastage of resources. For example, if the truck is half-empty, adding a few cartons for another vertical programme does not change the cost, that is integration.” (Medical Supplies Division, MoH)

In many cases there was uncertainty:

“Integration, does that mean workplan sharing, integrating logistics or does that mean moving STIs to MCH [Mother and Child Health]? … So that leads to (the question) is integration at the service level, all services under one roof, or all services in one room, or is it planning that is integrated?” (Family Planning Unit, RCHS, MoH)

In general none of the central-level respondents were clear about how to operationalise integration: “It does not come with detailed instructions on how to use it,” reported one MoH official, frustrated by the frequent use of the term in documents on reproductive health and health sector reform. However, as one donor observed:

“It is difficult to talk about integration in a country where even vertical programmes like the STI programme are not working.” (Donor)

Health sector reform: co-ordination and role confusion

Reproductive health initiatives and health sector reform share common goals of increasing equity and efficiency through improving access to high quality services.Citation14 Historically, the inability of the MoH to deliver services that achieved the measurable outputs demanded by donors resulted in the birth of vertical programmes. Where individual reproductive health programmes, such as STI control, retain vertical management structures, efficiency depends on how well they are co-ordinated and avoid duplication with integrated programmes. MoH reports had made clear that not only should there be integration at the point of service delivery but that management functions were also to be integrated at different levels:

“The vertical programmes should be redesigned so that the components which are common to all programmes (district based planning, supplies, training and Health Management Information Systems) be integrated into the district system, and their specialist management, monitoring and evaluation be kept as central functions.” Citation13

Central level programme managers were of the view that a degree of vertical management at the centre was essential to ensure efficiency, while integration needed to be operationalised at the district and delivery level. Although programme managers and other MoH officials had been assigned the responsibility of coordinating programmes, in line with government policy, some perceived “health sector reform” as another programme or project. This view was perpetuated by the location of the HSR Secretariat, isolated in the upper ranks of the MoH and lacking links with, and marginalised from, the technical implementing sections of the MoH (). As a result, many central and district players perceived HSR as a well-funded vertical programme, not as a vision or framework for reforming the health sector.

“It is our responsibility to run our projects, while it is the responsibility of the Health Sector Reform to ensure that the pieces work together.” (CBHC, RCHS, MoH)

“The responsibility of this unit is to promote IEC [Information, Education, Communication] to educate others on health. It is the responsibility of the Health Sector to build capacity and spearhead reorientation of clinicians and reproductive health providers for integration.” (IEC Unit, NACP, MoH)

Lacking the power to undertake its overall responsibility for coordinating and reforming the health sector, HSR's role was largely restricted to investing in infrastructure and training at the district level. At the central level, it was unable to implement the institutional changes necessary to improve coordination and promote integration of vertical programmes. HSR has no full-time “guardians” or “representatives” within the technical units at the central level, to facilitate understanding and ownership of the reforms. Respondents at the district level reported that directives from HSR did not correspond to and often conflicted with those from technical implementing programmes.

“…the issue of integration is a problem, We are told that the integration is supposed to be at district level while it is not at Ministerial [central] level… Even the Health Sector Reform is talking about this but the Ministry itself is not integrated, these are the problems. We've been trying to do it [integration], but get problems from the top.” (DHMT member)

Lack of definition and clarity around new roles, and shifts of responsibilities between the centre and the periphery, had led to significant “role confusion” at the district level. District staff perceived that the central and regional levels continued to play by the “old rules” while the district was trying to learn and apply the “new rules”, in a decentralised health system.

“The health sector reform shows that policy is made at Ministerial level [central level] and we implement it, the directive comes from the top. But… at the same time they say we are decision-makers and the implementers, yet we are just their tools. That is the confusion we feel.” (DHMT member)

Non-integration of STI control

Respondents at all levels reported that the partial integration of reproductive health programmes taking place at the central level was evident to them, impacting particularly on district level STI control. Those programmes that had been brought together under the RCHS section () were operating in a more coordinated way, allowing co-ordinated planning, management and decision-making to take place in districts and to some degree at the central level. However STI control was being managed from the central and regional levels as a vertical programme. Respondents at all levels reported resulting problems, one example being the conflicting ways in which condoms were being promoted. Condoms were being promoted by the RCHS as a family planning method, whereas, social marketing of condoms was focused on the role of condoms in STI/HIV prevention, targeted particularly at men. This made it difficult to promote condoms as a family planning method that could also prevent STI/HIV transmission within marriage. Lack of coordination and communication between STI Control and RCHS at the central level meant that negative effects on the family planning programme were being ignored.

“There are family planning condoms and others for STIs, but they are all condoms—it seems at the central level they see this differently!” (DHMT member)

Most district staff believed that fuller integration could increase efficiency, for example through common systems, rather than each programme (STI, Essential Drugs Programme and the units within RCHS) ordering and distributing drugs and other essential commodities separately. They expressed frustration at the inefficiencies that resulted from a failure at the central level to integrate support functions. While this was a particular problem for STI control, it exemplified a more general failure to integrate support functions at higher levels of the health system, and poor communication from those levels with districts.

“One of the issues is the drugs for STIs. We wanted to know why these drugs couldn't be distributed via MSD [Medical Stores Department] like other drugs directly to us at the district… We were not permitted to interfere, we in the periphery still just receive the orders, and if we choose to do it differently in our district and it does not work we're in trouble; if it works they praise themselves.” (DHMT member)

“Three weeks ago, I tried to phone MSD [the phone was broken]; then I tried again and they said these drugs would be sent, but up to today we have not received them. So, we don't know where the problem is: whether the drugs are not available or something else. There is a breakdown of communication, because last week we got EPI [Expanded Programme of Immunisation], but not family planning, today we got EDP [Essential Drug Programme] kits, but not family planning. Why isn't there a way for everything to come together at the same time?” (RCHS Co-ordinator)

Analysis of the relationship between districts and regions, specifically around management of the STI programme, helps to explain these inefficiencies. At the time of the study, STI Control at the central level was the responsibility of the National AIDS Control Programme (), managed by regional STI coordinators under the direction of Regional Medical Officers. STI drugs and reagents for syphilis testing were distributed to districts through regional headquarters, whereas supplies for other reproductive health services were distributed directly from the central level to the districts. The result was duplication of roles and parallel drug distribution systems, with frequent delays in the arrival of essential commodities to districts. DHMTs, who reported a clear preference for an integrated supply system, believed that some central and regional managers were resisting this.

Fear, power and autonomy

A consistent comment at all levels was that fear at the central and regional levels of losing power and resources was slowing the transition from vertical to integrated programmes, in that integration would mean the merging of programmes and funds, with the possibility of redundancies. This fear was sometimes ascribed to managers' and policymakers' fears of how donors who favoured vertical programmes and projects might respond. Central level respondents were also concerned that integration could result in the loss of technical quality in service delivery. Despite decentralisation, the National AIDS Control Programme wished to retain its link with regions, which was a remnant of its successful regional HIV/AIDS programmes from the early 1990s. This regional focus would change if STI Control were to join the RCHS, which was working directly with districts.

The history of the STI programme in Tanzania helps to explain the resistance to integrating programmes. Of particular relevance is the European Union-funded, community-based, randomised, controlled trial in Mwanza region.Citation15 The trial demonstrated that improved STI case management at the community level resulted in an important and significant reduction in the incidence of HIV infection among men and women of reproductive age in rural Tanzania. The success of this trial influenced the decision of the European Union to fund STI control in most regions across Tanzania, implemented through a regional rather than a district approach.

At the time of this study (2000–2001), however, future funding for the STI programme was uncertain. The proposed move of STI Control to the USAID-funded RCHS, as well as making for a more integrated Reproductive and Child Health Programme, could help remove that uncertainty. But such a move would create its own uncertainties for staff associated with STI Control. It was also planned that the newly formed Tanzania AIDS Commission (TACAIDS), under the Prime Minister's Office, would take over the advocacy roles of the National AIDS Control Programme, leaving it smaller, less influential and less well-funded than before. Respondents at all levels perceived that some national and regional managers were seeking to retain control of the residual vertical reproductive health programmes, including STI control and syphilis testing for pregnant women.

“There is… resistance from [central level] programme officials, there is vested interest—they receive their own funding, they fear that with integration they will lose control over resources; now to move to another unit means they lose control by putting it into the big bundle with the RCHS.” (UN agency)

“You tell me to integrate, but there is fear; although we say we are integrated, we are not; there is fear of integration. People in the projects are afraid of losing their position.” (NGO)

“One of the fears is losing donor support, they are not sure if they integrate whether they will lose financial support… There are worries that there would be loss of accountability, programme identity and credibility. And then who would ultimately be responsible?” (EPI unit, RCHS, MoH)

DHMT members were equally or even more forthright than central level respondents in citing reasons why integration was being implemented in a piecemeal fashion, with retention of vertical management structures at higher levels.

“The core of the problem is at the top. Integration for us is not a problem; we can make the necessary changes. It seems there is some resistance to integration at Ministerial [central] level. These reforms might cause some individuals to lose their power and others to gain. Human nature does not allow a person to surrender power early [laughter] without resistance.” (DHMT member)

The theory of health sector reform is that DHMTs have the power and autonomy to decide how to implement programmes and deliver services. However, in practice, the source of funding and the control associated with those funds meant that most districts continued to implement programmes according to central level—partly donor-influenced—directives. Moreover, in the absence of clear and consistent directives from higher levels, reinforcing the MoH's new “hands-off” policy, most districts were not prepared to take the initiative and use their decentralised powers to make decisions.

“Normally, power is not given easily, and anyone with power won't relinquish it easily. It has to be taken from him. The implementation of decision-making at district level will be very hard. It is mentioned in various documents, in various health sector reform guidelines, but actual implementation is difficult. I feel that there will still be interference from the higher levels even though the decision is ours to make.” (DHMT member)

Human resources: low capacity and morale

Despite widespread enthusiasm for the reforms and their desire to see the integration process completed, most DHMTs expressed reservations around their capacity to undertake some of the new responsibilities assigned to them, especially supervision. Facility-based supervision was usually carried out jointly by a team of three DHMT members. None of them generally had sufficient knowledge or skills to carry out clinical supervision for more than one programme, let alone integrated programmes. Teams rarely managed to supervise all of a facility's services during one visit, despite supervision being primarily administrative. District teams openly admitted that quality assurance and clinical supervision were a rarity.

“If there are three members going for supervision during a particular day in a week, what they are going to supervise is related to their ability… They do not go to supervise on behalf of the Reproductive Child Health Co-ordinator or, say, Family Planning. They will only supervise their own activities, say STI or sanitary matters… So all the activities, which are carried out [in the facility] are not supervised during one visit. The next time [three months later]if the person involved with FP goes, she will focus on that only.” (Acting District Medical Officer)

An RCHS Coordinator reported that they were all “fumbling” with regard to supervising health workers in STI management: “When you ask us questions [about STIs], we don't know heads or tails about this.” District level respondents said the problems were due to the failure to build district level supervisory skills, especially clinical skills, as well as top-down planning. They reported that the health workers they supervised were sometimes more knowledgeable than the supervisors themselves on specific components of reproductive health, and that the supervisors needed training. Training of district supervisors to undertake clinical supervision of STI care, which was not yet integrated within RCHS, had not taken place. Yet, in practice, district staff were attempting to provide it:

“We were given a few instructions on supervision, but very little… We DHMT need this training so we can integrate supervision—supervision is more than a checklist, but when you don't know about STIs [for example] you have to rely on the [supervision] checklist; not so?” (District Cold Chain Co-ordinator)

DHMT members were unhappy about lack of recognition and reward, in the light of the many new tasks and responsibilities assigned to them by the central Ministry. The issue of how incentive systems worked, low salaries of district staff and their perception that central government officials were benefiting most, were initially taboo subjects but emerged towards the end of most focus group discussions. Low salaries, inadequate to meet basic needs, were somewhat compensated for by more generous per diems, especially when staff left their districts to attend meetings elsewhere.

“The issue of salary… it's been on the agenda for many years. When I went for studies…[overseas], I found I was the least paid doctor in the world! [laughter]… But if I go [out of my district] for a whole week I get 30,000 shillings a day as per diems [US$45 per week]. I get more in one week outside my district than I do in my monthly salary. The donors pay the per diems while the government pays the salaries. The government is using donor money to give incentives to the higher officers and ignoring the ones at the lower levels. So the donors wanted to increase salaries and lower per diems, but the government refused. We as DHMT have a very slim chance of convincing the policymakers otherwise.” (District Medical Officer)

The impression being given to district staff was that training and the rewards it brings were ends in themselves, rather than the means to improve and be rewarded for delivering high quality services. This was reflected in policy documents and the implicit messages they were receiving from higher levels of the system, from both donors and government. The indicators proposed to measure progress in human resource development under Tanzania's health sector reforms illustrate this:

“…the proportion of health facilities with staff qualified to a specific standard; and the proportion of District Health Management Teams, Regional Health Management Teams and District Health Boards that have undertaken training including planning, management, health economics and financing.”Citation13

Discussion

Our findings illustrate that district health workers and programme staff are struggling to integrate existing initiatives, lacking adequate resources, coherent policy direction and capacity to undertake the tasks required of them, and are having to deal with disjointed policy directives from higher levels.

The findings support the conclusions of Lubben et al that there has been inadequate dialogue at the policy level between the reproductive health and health sector reform communities.Citation9 Here, as elsewhere, attempts to link policies addressing reproductive health and health sector reform have not been operationalised. Contradictions may arise from the different perspectives of the two communities, who speak different languages, the former an advocacy and service delivery language and the latter a “managerial-technocratic” language.Citation9 Citation16

The findings also suggest that uncertainty around future donor intentions and fear of losing financial support weigh heavily on managers at the central MoH level. Moreover, MoH structures reflect the contradictory influence of different donors. The Health Sector Reform Secretariat has relied heavily on support from one bilateral donor, which sought to drive an overall reform of the health sector. However, HSR has remained disconnected and has had limited influence on reproductive health programmes, which have relied on support from other donors. In theory, the implementation of a sector-wide approach (SWAp), where donors and government jointly pool and disburse funds in a co-ordinated way, should prevent the piecemeal, fragmented approach that comes with separately financed and planned programmes. However, this assumes the participation of all donors in this process. Some donors are partly committed to co-ordinated funding, while continuing to vertically fund some projects, whereas others rely on vertical approaches, over which they have more control.

In practice, implementation of the SWAp in Tanzania has therefore been slow and the MoH at the central and district levels has continued to be heavily dependent on funding from a wide range of donors. Some, including several bilateral donors, have been committed to the reform and integration process, yet they continue to channel some or even much of their money into specific projects. Other donors and NGOs still support only the funding and implementation of vertical programmes and projects, especially high-profile priorities such as HIV/AIDS, where results can more easily be attributed to their own inputs.Citation6

In 2003, the challenges of implementing the ICPD Cairo agenda have become even more apparent as the importance of HIV/AIDS control grows. The comprehensive vision of integrated sexual and reproductive health care faces challenges at the delivery and managerial level, through lack of capacity of district staff and poorly co-ordinated logistical support. At the planning and funding level, fear of losing resources and fear of losing track, especially if impact cannot be demonstrated, mean that the drive to put in place comprehensive, integrated programmes has become stalled. If these contradictions are not resolved, it could result in a worst-case scenario: (i) poor quality services, because district staff do not have the capacity to supervise and assure quality, and (ii) inefficient management, due to poorly co-ordinated, parallel planning and support systems. The degree of criticism articulated by district staff of performance at the central level is not routinely expressed by those working and living at lower levels, given such a hierarchical system, and expresses the frustration they feel at being given the responsibility but not the necessary resources or support to provide these services.

HIV/AIDS control initiatives may bring new opportunities—or threats—if the goals of improved and equitable access to high quality Reproductive and Child Health services are to be achieved.Citation17 The advent of new financing mechanisms, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, brings pressures to establish new vertical management structures and monitoring and evaluation systems, to satisfy contributors' demands for evidence of impact.Citation18 Reproductive and child health and HIV/AIDS programmes—and more broadly the goal of health sector reform—may be submerged if they are unable to cope with these new global health initiatives.

Conclusion

Uncertainty around what is meant by integration reflects the uncertainty that national programme managers feel, working in a policy environment which is determined by their perceptions of where power lies, which is usually with the donors who provide the funds for programme implementation. National policymakers have attempted to chart a map for reforming the health sector. However, district staff believe that programme managers at the central level are motivated more by a fear of losing resources and power, than by a willingness to implement the reforms. Underlying this fear is their relative lack of power in dealing with donors. This is compounded by uncertainty around future donor intentions and donor “fashions”. Three things (and probably more) are needed, if the provision of comprehensive and accessible reproductive health services is finally to become a reality:

co-ordinated and sustained resource commitments from wealthy countries, which support developing country-led policymaking;

national programme managers to strengthen their links with, and their support for, district and service delivery staff, turning the rhetoric of reform into reality; and

the introduction of a revised incentive system and salaries, targeted at district staff, that build their morale and reward them for delivering good quality reproductive health services.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Ministry of Health, Tanzania, for permission to carry out the study, AMREF Tanzania for their technical and administrative support, in particular Daraus Bukenya (Country Director), Vera Pieroth (AIDS Advisor), Ole Sepere, Agnes Ndyetabula (Research Assistants) and study participants for their interest and commitment. The research on which this paper is based appears in full as a doctoral thesis by Monique Oliff, “Integration of STI services into reproductive health services in Tanzania: an operational analysis of opportunities, barriers and achievements”, University of London, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2002. The study was funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), UK (Innovations Grant No. SCF296).

References

- United Nations. Programme of Action, International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 1994. 1994; UN: New York.

- K Hardee, KM Yount. From Rhetoric To Reality: Delivering Reproductive Health Promises through Integrated Services. 1995; Family Health International: Research Triangle Park NC.

- KR O'Reilly, KL Dehne, R Snow. Should management of sexually transmitted infections be integrated into family planning services: evidence and challenges. Reproductive Health Matters7(14): 1999; 49–59.

- L Gilson, A Mills. Health sector reforms in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons of the last 10 years. Health Policy32: 1995; 215–243.

- A Mills, GP Vaughan, DL Smith. Health System Decentralization: Concepts, Issues and Country Experience. 1991; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- A Brown. Current issues in sector-wide approaches for health development, Tanzania case study. 2000; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- S Hanson. Health sector reform and STD/AIDS control in resource poor settings—the case of Tanzania. International Journal of Health Planning and Management15: 2000; 341–360.

- S Rifkin, G Walt. Why health improves: defining the issues concerning “comprehensive primary health care” and “selective primary health care”. Social Science and Medicine23: 1986; 559–566.

- M Lubben, SH Mayhew, C Collins, A Green. Reproductive health and health sector reform in developing countries: establishing a framework of dialogue. Bulletin of World Health Organization80(8): 2002; 667–674.

- L Lush, G Walt, J Cleland. Defining integrated reproductive health: myth and ideology. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 77(9): 1999; 771–777.

- SM Mayhew, L Lush, J Cleland. Implementing the integration of component services for reproductive health. Studies in Family Planning. 31(2): 2000; 151–162.

- United Republic of Tanzania. The Health Sector Reform Programme of Work—July 1999–June 2002. 1998; Ministry of Health: Dar es Salaam, 1–66. Draft.

- United Republic of Tanzania. Joint MOH/Partner Appraisal of Health Sector POW and POA. 1999; United Republic of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam.

- K Hardee, J Smith. Implementing Reproductive Health Services in an Era of Health Sector Reform. 2000; Policy Project, Futures Group International: Washington DC, 1–32.

- H Grosskurth, F Mosha, J Todd. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 346(8974): 1995; 530–536.

- H Standing. An overview of changing agendas in health sector reforms. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(20): 2002; 19–28.

- A Papineau Salm. Promoting reproductive and sexual health in the era of sector-wide approaches (SWAps). Reproductive Health Matters. 8(15): 2000; 18–20.

- R Brugha, G Walt. A global health fund: a leap of faith?. British Medical Journal. 7305: 2001; 152–154.