Abstract

Sex workers have high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), many of them easily curable with antibiotics. STIs as co-factors and frequent unprotected exposure put sex workers at high risk of acquiring HIV and transmitting STIs and HIV to clients and other partners. Eliminating STIs reduces the efficiency of HIV transmission in the highest-risk commercial sex contacts—those where condoms are not used. This paper reviews two STI treatment strategies that have proven effective with female sex workers and their clients. 1) Clinical services with regular screening have reported increases in condom use and reductions in STI and HIV prevalence. Such services include a strong peer education and empowerment component, emphasize consistent condom use, provide effective treatment for both symptomatic and asymptomatic STIs, and begin to address larger social, economic and human rights issues that increase vulnerability and risk. 2) Presumptive treatment of sex workers, a form of epidemiologic treatment, can be an effective short-term measure to rapidly reduce STI rates. Once prevalence rates are brought down, however, other longer-term strategies are required. Effective preventive and curative STI services for sex workers are key to the control of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, and are highly synergistic with other HIV prevention efforts.

Résumé

Les professionnel(le)s du sexe connaissent des taux élevés d'infections sexuellement transmissibles (IST) répondant souvent aux antibiotiques. Les IST comme cofacteurs et les relations sexuelles non protégées mettent les professionnel(le)s du sexe à haut risque de contracter le VIH, et de transmettre le virus et des IST à des clients et autres partenaires. Eliminer les IST réduit la transmission du VIH dans les contacts sexuels commerciaux à plus haut risque—quand les préservatifs ne sont pas utilisés. Cet article examine deux stratégies qui se sont révélées efficaces avec les professionnelles du sexe et leurs clients. 1) Des services cliniques avec tests réguliers ont abouti à un accroissement de l'utilisation de préservatifs et à la réduction de la prévalence des STI et du VIH. Ces services comprennent un fort élément d'éducation par les pairs et d'autonomisation, préconisent l'emploi de préservatifs, fournissent un traitement efficace pour les IST symptomatiques ou non, et abordent les questions sociales, économiques et des droits de l'homme plus larges qui accroissent la vulnérabilité et les risques. 2) Le traitement présomptif des professionnelles du sexe peut être efficace à court terme pour réduire rapidement les taux d'IST. Néanmoins, une fois que la prévalence a diminué, d'autres stratégies à long terme sont nécessaires. Des services de prévention et de soins efficaces pour les professionnelles du sexe sont fondamentales pour lutter contre les IST, notamment le VIH, et exercent une forte synergie avec d'autres mesures de prévention du VIH.

Resumen

Las trabajadoras de sexo tienen altas tasas de infecciones transmitidas sexualmente (ITS) que se pueden curar con antibióticos. El riesgo de adquirir el VIH y de transmitir las ITS y el VIH a sus clientes y otras parejas es alto debido a las ITS como co-factores y a la frecuente exposición sin protección. Eliminar las ITS reduce la eficiencia de la transmisión de VIH en los contactos sexuales comerciales de alto riesgo—cuando no se usa condón. Este artı́culo examina dos estrategias de tratamiento de ITS de probada eficacia con trabajadoras de sexo y sus clientes. 1) Los servicios clı́nicos con despistaje regular han reportado aumentos en el uso del condón y reducciones en la prevalencia de ITS y VIH. Dichos servicios incluyen un fuerte componente de educación entre pares y empoderamiento, un énfasis en el uso consistente del condón, provisión de tratamiento eficaz para las ITS sintomáticas y asintomáticas, y empiezan a abordar los asuntos sociales, económicos y de derechos humanos que aumentan la vulnerabilidad y el riesgo. 2) El tratamiento presuntivo de trabajadoras de sexo, una forma de tratamiento epidemiológico, puede ser una medida eficaz a corto plazo para reducir rápidamente las tasas de ITS. Una vez que se haya reducido la tasa de prevalencia, sin embargo, se requieren otras estrategias a largo plazo. Los servicios de ITS preventivos y curativos eficaces para las trabajadoras de sexo son claves para el control de ITS incluyendo el VIH, y funcionan en alta sinergia con otros esfuerzos de prevención de VIH.

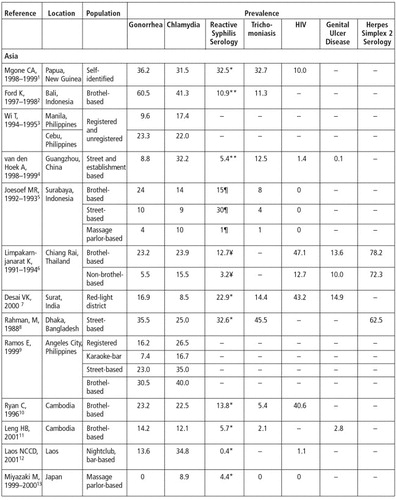

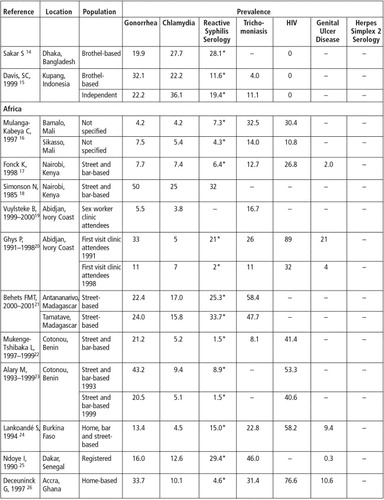

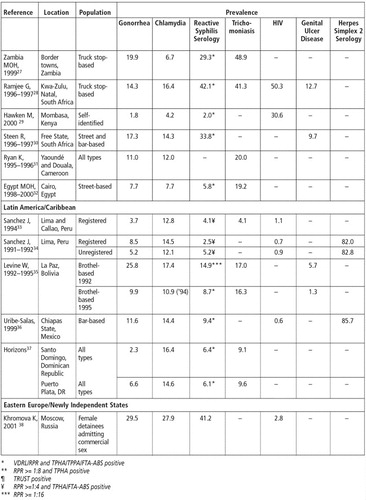

Sex workers often have high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), many of them easily curable with antibiotics (Table 1)Citation1Citation2Citation3Citation4Citation5Citation6Citation7Citation8Citation9Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15Citation16Citation17Citation18Citation19Citation20Citation21Citation22Citation23Citation24Citation25Citation26Citation27Citation28Citation29Citation30Citation31Citation32Citation33Citation34Citation35Citation36Citation37Citation38. In commercial sex settings where condom use is inconsistent and access to effective STI treatment limited, half to two-thirds of women working as sex workers typically have a curable STI at any one time. In some settings, 10% or more have an active genital ulcer and over 30% reactive syphilis serology. Gonorrhoea and chlamydia are often found in a third or more of sex workers, trichomoniasis is common, and many women have multiple infections. Where testing has been done, over three out of five sex workers have evidence of herpes infection. Regardless of the region, poor access to services correlates with high STI prevalence.

These STI co-factors and frequent unprotected sexual exposure also put sex workers at high risk of acquiring HIV and of transmitting STIs and HIV infection to their clients and other partners. Such transmission dynamics in commercial sex can sustain high STI incidence and prevalence in wider sexual networks. Epidemiologic surveillance has consistently confirmed the role of commercial sex in driving heterosexual HIV transmission, especially in early epidemics.Citation39

Clients and other partners of sex workers also have high rates of STIs and HIV,Citation 40 and serve as both a constant source of re-infection for sex workers and as a transmission bridge to the general population. Effective STI control among sex workers and their clients and partners would thus be beneficial for sex workers as well as have potentially large public health benefits for the general population. Such benefits would include:

| • | reduced burden of disease and fewer STI complications (such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility and ectopic pregnancy) for the sex workers themselves, | ||||

| • | reduced transmission and prevalence of STIs (and their complications) among sex workers, their clients and regular sex partners, and | ||||

| • | reduced efficiency of HIV transmission within the sexual networks most important to HIV transmission. | ||||

This last effect can be especially large in areas where genital ulcer disease (GUD) is common. Ulcerative STIs increase transmission efficiency of HIV by up to 300 times, raising low infection probabilities to as high as one in twelve.Citation41Citation42Citation43 This effectively amplifies transmission through commercial sex networks that in turn drive generalized HIV epidemics.

Effective STI control in commercial sex is feasible and has been achieved in diverse settings. When STI interventions are implemented with the active involvement of sex workers themselves, chances for success are greater and additional benefits accrue—increased sexual health knowledge and skills acquired by sex workers lead to greater diffusion of prevention information through often hard-to-reach transmission networks. Rather than remaining passive recipients of services, sex workers can become “part of the solution”.Citation44

This paper reviews several public health strategies that have been employed for reducing STI transmission in commercial sex networks, with emphasis on STI treatment strategies that have proven effective for women sex workers. Related and complementary interventions that are beyond the scope of this paper include efforts to directly increase condom use and reduce STI prevalence among the clients and regular partners of sex workers, and among male sex workers. Also not discussed in detail is the broader structural, legal and policy environment in which sex work takes place, which frames vulnerability and risk, and greatly influences STI transmission dynamics.

Public health approaches to STI control

Attempts to reduce STI transmission in commercial sex networks date back to times of earlier STI pandemics. In the 19th century, the link between commercial sex and syphilis spurred efforts to repress prostitution and reform prostitutes, which did little more than drive sex work underground. Regulatory approaches—which attempted to diagnose and treat STIs in sex workers and/or curb the activity of women with infection—were limited in part by their lack of accurate diagnostic tools and effective treatment. The prevalence of syphilis and other STIs eventually declined in Europe and North America in spite of these efforts, however. The discovery of antibiotics and improvements in STI diagnostics contributed to better STI control, but reductions on the supply side of commercial sex that accompanied economic development and improvements in women's status were probably more important.Citation45

More recently, efforts to reduce STI prevalence among sex workers have concentrated on three areas of intervention:

| • | increasing condom use between sex workers and their clients, | ||||

| • | improving identification and treatment of curable STIs, and | ||||

| • | reducing demand for commercial sex (largely by means of risk reduction messages targeting men). | ||||

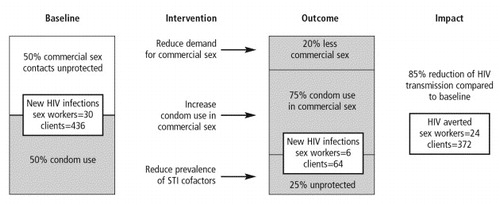

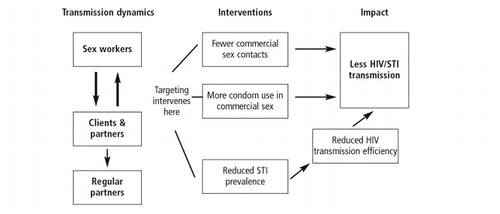

Interventions to reduce STI prevalence among sex workers are synergistic with condom promotion and other sex worker prevention efforts (“care–prevention synergy”).Citation46 illustrates how these three interventions act in different ways to reduce transmission. First, reducing demand for commercial sex reduces the number of potential exposures. Second, increasing the proportion of remaining commercial sex acts protected by condoms reduces exposure further. Third, STI interventions act to reduce transmission efficiency during remaining sex acts, both commercial and non-commercial, where condoms are not used.

Figure 1 A model of targeted interventions for interrupting transmission dynamics in commercial sex settings

As an example, illustrates the number of new HIV infections that would be expected among 1,000 sex workers (50% HIV prevalence) and their clients (5% HIV prevalence) under two different scenarios. The first scenario assumes 50% condom use, 10% prevalence of genital ulcers and 25% prevalence of non-ulcerative STI. The second reflects a 20% reduction in demand for commercial sex, 75% condom use, 80% reduction in genital ulcers and 40% decline in non-ulcerative STI. The AVERT model projects HIV infections averted over one year in both sex worker and client groups.Citation 47 Assuming sex workers have 100 different clients per year and an average of two contacts per client, AVERT estimates 81% fewer HIV infections among sex workers and 85% fewer among clients. Similar estimates of the efficiency of targeted interventions for sex workers have been made, based on data from Nairobi.Citation48

Thailand successfully applied these principles on a national scale in the early 1990s. Targeting communication, condom and STI interventions to commercial sex settings, they intervened successfully in these same three areas. Fewer men reported commercial sex contacts, consistent condom use in commercial sex increased from 14% to over 80% and the incidence of curable STIs decreased over 95% during the decade. At the same time HIV prevalence in the general population stabilized and eventually declined.Citation49Citation50 Similar trends from interventions targeting communication, condom promotion and STI care have been reported from Cambodia, and among sex workers in Nairobi, Abidjan and Cotonou.Citation11Citation51Citation52Citation53

Even successful interventions such as these can be strengthened. Direct STI control interventions should always be complemented by efforts to improve the conditions that increase vulnerability and the limited access to services in communities where sex work takes place. The health and human rights of targeted populations must be seen not only as elements of STI control strategies, but as legitimate ends in themselves.

STI treatment strategies for sex workers

Effective STI control among sex workers is a critical element in the above models. Eliminating STI co-factors greatly reduces efficiency of HIV transmission in the highest risk commercial sex contacts—those where condoms are not used. Moreover, effective STI control involving sex workers can have a significant impact on the burden of STIs in the general population. How then can STI prevalence among sex workers be reduced?

A review of STI control strategies involving sex workers reveals several categories of potential interventions with different strengths and weaknesses. All include a strong emphasis on consistent condom use as essential primary prevention. Specific STI treatment strategies include:

| • | Diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic sex workers on clinical, etiologic or syndromic grounds is probably the most commonly used clinical response, but is constrained by reliance on symptoms to identify individuals with infection. Most women (and many men) with STI are asymptomatic. Clinical approaches have the additional limitation of being imprecise, and accurate aetiologic diagnosis requires laboratory tests that are often not available in low-resource settings, due to expense or logistics. Syndromic management solves some operational problems (immediate treatment reduces loss to follow-up) but similarly cannot be applied unless patients have symptoms. | ||||

| • | Regular screening of sex workers regardless of symptoms with clinical examination, augmented where possible with laboratory tests, overcomes the problem of asymptomatic infections. Regular screening and treatment with high quality diagnostics, where available, can be highly cost-effective, given sex workers' high rates of curable STI. This approach is often limited by poor performance of locally available screening methods, however, and by lack of screening tests for many infectious aetiologies. | ||||

| • | Presumptive treatment of sex workers regardless of symptoms addresses both problems of asymptomatic infections as well as the limitations and cost of screening tests. Presumptive treatment given on a one-time or periodic basis has been shown to be effective in rapidly lowering STI prevalence, but requires longer-term strategies to maintain low rates. | ||||

Combinations of the above approaches are possible that address both symptomatic and asymptomatic sex workers. Asymptomatic infections among women in general comprise, in fact, the major STI management challenge. A related problem is that the most common symptom in women, vaginal discharge, is usually due to non-sexually transmitted reproductive tract infections (RTIs) and is not a good indicator of STI.Citation 54 The following sections discuss how screening and presumptive treatment can be used to address these obstacles.

Sex worker screening programmes

Clinical services for sex workers that include regular screening coupled with prevention messages have reported increases in condom use and reductions in STI and HIV prevalence. Regular screening and treatment services for sex workers in Senegal (where sex work is legal) have been credited with contributing to low and stable HIV seroprevalence.Citation55

A comprehensive approach to STI prevention and care was taken at Projet SIDA in Kinshasa, Zaire, where condom use and voluntary clinic attendance were promoted within networks of sex workers.Citation 46 Regular screening for curable STIs was conducted using sensitive laboratory tests. Over the life of the project, condom use increased and STI prevalence and HIV incidence decreased significantly. Similar strategies (clinical screening and peer education components), with comparable impact on condom use and STI rates, have been reported from La Paz, Abidjan, Cotonou and Nairobi.Citation20Citation35Citation53Citation56

Despite the documented success of this approach, regular screening using sensitive laboratory tests has not been widely replicated beyond research and demonstration project settings in countries with limited resources, probably because of the expenses involved (related to the establishment and maintenance of the laboratory infrastructure, trained laboratory technicians and recurrent costs of diagnostics). Attempts to develop less expensive algorithms for detection of STIs (primarily cervical infections) in sex workers, based on risk factors, clinical signs and microscopy have been reported from Côte d'Ivoire, Senegal and the Philippines.Citation3Citation25Citation57 Results (among populations of sex workers with gonorrhoea and chlamydia prevalence rates of 20–35%) suggest that such approaches perform better than in general population women with lower STI rates. While facilities for speculum exam and microscopy may not be universally available, this approach is more feasible for widespread application than screening using gonorrhoea cultures or current chlamydia testing technologies. Still, the limitations of this approach should be recognized—two-thirds of all women screened in the Abidjan study received treatment, and one in seven infections were missed. Authors of several of these studies noted that treating all sex workers (presumptive treatment) might be a more effective and cost-effective alternative. Such an approach would treat all infections (100% sensitive) whether symptomatic or not, and could be used at a sex worker's first visit (when STI prevalence is highest) or on a periodic basis.

Experience with presumptive treatment of sex workers

Presumptive treatment of sex workers is a form of epidemiologic treatment (treatment of individuals or populations with a high likelihood of having disease). The decision to give STI treatment is based not on the presence of symptoms, signs or laboratory tests, but on increased risk of exposure—a defining feature of sex work where condom use is not the rule. Epidemiologic treatment of sex partners (contact tracing or partner referral and treatment), an accepted component of STI control, is justified on similar grounds. In presumptive treatment, full treatment doses of antibiotics are given to treat probable infection. Presumptive treatment also has some prophylactic effect, depending on the pharmacokinetics of the drugs used and treatment intervals. Single-dose antibiotics are available that have long half-lives and broad STI coverage (see Table 2).

Table 2 Select antibiotic treatment regimens used for presumptive treatment (PT) of sex workers

The public health rationale for presumptive treatment of sex workers is based on STI epidemiology and the limitations of other clinic-based strategies.Citation58Citation59 Because of high rates of partner change, sex workers are frequently exposed to STI and, when infected, are capable of transmitting infection to many susceptible partners. For this reason, the number of secondary infections averted by preventing or curing STIs in core groups of sex workers has been estimated to be more than 100 times greater than would be prevented by treating the same number of cases in the general population.Citation60Citation61 Presumptive treatment of the most epidemiologically important core groups can thus be an efficient and cost-effective approach to reducing STI prevalence in the general population.

The primary objective of presumptive treatment strategies is to achieve a rapid reduction in prevalence of infection. By definition, therefore, presumptive treatment strategies are temporary measures—as prevalence falls, the epidemiologic justification for the intervention becomes weaker. In order to maintain reduced prevalence levels, other more sustainable control measures, such as primary prevention and improved case management, must be in place and strengthened.

Early experience with targeted epidemiologic treatment of sex workers for STI control was mixed.Citation 62 Holmes reported on gonorrhoea control implemented near a US naval base in the Philippines in the 1960s. After four months of weekly screening and treatment, gonorrhoea prevalence in sex workers fell from 11.9% to 4.0%, and the incidence of new infections among servicemen was halved. A single round of epidemiologic (presumptive) treatment temporarily reduced prevalence further to 1.6%, but the added effect of one dose of presumptive treatment lasted only a short time. The experience confirmed that targeted sex worker services—in this case, weekly screening and treatment—could reduce sex worker STI prevalence as well as transmission beyond the core group.

Jaffe reported in the 1970s on a syphilis epidemic in the US among California farm workers.Citation 63 A control programme that included presumptive treatment of sex workers led to decreases in incidence of infectious syphilis by 51% among prostitutes and 27% among farm workers. Similarly, outbreaks of chancroid in Orange County, California and Winnipeg, Canada were easily brought under control by focusing efforts on sex workers and their clients.Citation64Citation65

One-time presumptive treatment may be effective in controlling isolated STI outbreaks, but some kind of periodic treatment may be necessary to achieve control in more endemic areas. Sex workers in Surabaya, Indonesia have received regular presumptive treatment for syphilis since 1957.Citation 66 Prevalence of reactive non-treponemal antibody serology among registered prostitutes fell from 87% in 1957 to 1.5% in 1992, likely due to both presumptive treatment and a mass treatment campaign against endemic yaws.

Periodic presumptive treatment was used in a South African mining community where tens of thousands of male migrant workers live apart from their families in single-sex hostels.Citation 30 Baseline prevalence of gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia in a core group of women at high risk living in areas around the mines was 24.9%, and 9.7% of the women also had clinical evidence of genital ulcers. The Lesedi project sought to reduce the prevalence of curable STIs by providing monthly presumptive treatment (azithromycin 1 gram) to the sex workers along with prevention education and condoms. After nine months, rates of curable STIs declined between 70% and 85% for women using the services, and reported condom use with clients increased. Among hostel-based miners living in the area of the intervention, prevalence of gonococcal/chlamydial infection fell by one-third and genital ulcers by almost 80%. Rates of symptomatic STIs seen at mine health facilities decreased among miners in the intervention area compared with miners living farther from the site and with less exposure to the project, and these decreases were sustained over four years of follow-up.Citation67

In Madagascar, presumptive treatment was evaluated in a pilot project in two cities where sex workers were screened for syphilis and offered presumptive treatment for bacterial STIs (azithromycin 1 gram plus ciprofloxacin 500 mg). Two months later, prevalence of cervical gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia declined 28% (from 30.4% to 21.9%) and the prevalence of active syphilis (RPR>1:8 with positive treponemal confirmatory test) fell 80% (from 14.6% to 2.9%). Based on these results, presumptive treatment was included in revised STI algorithms developed for and with the active participation of sex workers. Algorithms included speculum exams; syphilis treatment based on serologic screening; presumptive treatment for gonorrhoea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis during initial visits, and individual risk-based treatment at three-month follow-up visits.Citation21 No follow-up information has been reported.

An intervention in Angeles City, Philippines used a single round of presumptive treatment for sex workers to reduce STI prevalence, then attempted to improve routine prevention and screening services. Presumptive treatment (azithromycin 1 gram) was given to all women sex workers reached during a one-month period of enhanced outreach. Prevalence of gonorrhoea and chlamydia, measured by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) one month later and stratified by type of sex work, fell 41% overall (58% among the women who received presumptive treatment one month earlier). Reductions were significant for all groups and were related to coverage and mobility.Citation9

A syphilis prevention programme in Vancouver, Canada provided presumptive syphilis treatment (azithromycin 1.8 grams) to 1,055 sex workers on several occasions in January–February 2000.Citation68 A peer-based distribution technique called “secondary carry” was used to provide treatment to an additional 1,926 individuals at high risk. Reported cases of syphilis declined for six months but later rebounded to higher levels. As the authors point out, population mobility, incomplete coverage and importation of cases probably contributed to continued syphilis transmission. The short-term impact of one-time control interventions highlights the importance of ongoing prevention efforts to sustain reduced rates.

Operational issues for designing a comprehensive package of services

A number of operational issues are important to consider in designing a comprehensive package of services and replicating field interventions in different settings. These include the optimal interval between presumptive treatment (or screening) visits, how and when to taper or withdraw presumptive treatment, choice of antibiotics, the target STI pathogens and monitoring of antibiotic resistance both of STI and other community pathogens, such as respiratory or diarrhoeal. Primary parameters for such service delivery decisions are epidemiological (STI incidence and prevalence), behavioural (rates of partner change and condom use) and structural (commercial sex conditions, access to health care services and respect for human rights). Some of these issues have been partially addressed in interventions previously cited.

Presumptive treatment intervals

In the South African gold mining communities served by Lesedi, periodic presumptive treatment was initially given monthly because of high baseline prevalence of curable STIs, extremely low condom use (3%) and high HIV prevalence (estimated at 50%). As STI prevalence came down and condom use increased, periodic presumptive treatment frequency was reduced to every three months. Women were still encouraged to attend the clinic monthly and emphasis was shifted to condom use as the best protection against both curable and incurable STIs, including HIV. An evaluation following this periodic presumptive treatment tapering showed that prevalence of genital ulcer disease remained stable among women and miners in the area but non-ulcerative STI prevalence increased.Citation 69 This observation appears to be consistent with other experience with presumptive treatment—genital ulcers, particularly chancroid, respond most rapidly and are controlled more easily than non-ulcerative STIs. At condom use rates below 60%, there were apparently enough unprotected exposures to permit increased transmission of gonorrhoea and chlamydia. At another periodic presumptive treatment site in Carletonville, South Africa, tapering was introduced earlier but at higher reported rates of condom use (above 70%). No significant increase in any curable STI was measured.Citation70

An alternative approach is a single round of presumptive treatment to rapidly reduce prevalence followed by strengthening of other STI control measures, including regular screening. This model was adopted in Madagascar and piloted in Angeles City, Philippines.Citation9Citation21 Screening services in Angeles City were improved for brothel and street-based sex workers (but not for two types of registered sex workers) by broadening criteria for treatment to include clinical signs and cervical gram stain criteria. This resulted in more women receiving treatment. Six months later, prevalence remained below baseline for brothel (p<0.001), and street-based (p=0.05) sex workers, but had returned to baseline for the registered sex workers. The prevalence of gonorrhoea and/or chlamydia among clients of brothel-based sex workers declined from 28% to 15% (p=0.03) during this six-month period.

Choice of antibiotics

Single dose treatment effective against gonorrhoea, chlamydia, chancroid and incubating syphilis is feasible, and several possible combinations are summarized in Table 2.

Azithromycin 1 gram, the most commonly used, is the only single-dose, anti-chlamydia treatment available, and provides high cure rates for the above infections. Some guidelines recommend 2 grams of azithromycin for treatment of gonorrhoea, arguing that the higher dose will delay development of resistance. Gastro-intestinal side effects are very common at this dosage, however, which might discourage women from coming back for further presumptive treatment visits. An alternative would be to add another effective gonorrhoea treatment, such as cefixime 400mg, to azithromycin. Other antibiotics active against gonorrhoea have disadvantages. Ceftriaxone requires injection and gonorrhoea has developed resistance to quinolone antibiotics in several regions. Doxycycline and tetracycline (effective against chlamydial infection but not gonorrhea and chancroid) require seven days of treatment, posing adherence problems.

Whatever the antibiotic choice, careful monitoring for development of antibiotic resistance (including N. gonorrhoeae and any non-sexually transmitted pathogens for which the drugs are used) should be planned. This applies to other treatment strategies (syndromic management, screening and treatment) used with sex workers as well, and concerns about potential resistance should be considered in light of the benefits of reduced STI prevalence. Any antibiotic treatment of sex workers has the potential to select for resistant organisms for the same reasons that STI transmission in commercial sex is so efficient–sex workers are subject to high rates of exposure and have frequent contact with susceptible partners. Risk of resistance can be minimized by directly observed single-dose therapy that eliminates problems of poor adherence and sub-therapeutic doses.

Replicability

Replicating sex worker interventions such as those cited above requires adaptation based on an understanding of STI transmission dynamics in local commercial sex settings. Defining the operational details of interventions should thus be based on local data collected with the active participation of sex workers and others involved in commercial sex networks. Rapid assessments—including mapping, enumeration and behavioural components—can give a picture of the people, places, behaviours and context of commercial sex in a given area, as well as provide baseline data for intervention monitoring and evaluation.

Assuring participation of sex workers in data collection and intervention planning is a critical step. Women and men who perceive that health services are doing something for them are more likely to take prevention messages seriously. Involvement of sex workers themselves in the design and implementation of STI control and related services helps to ensure that services will be used, and is often the first step to improving conditions that increase risk and vulnerability.Citation 71 Sex workers themselves participated in algorithm development and intervention design in South Africa and Madagascar.Citation69Citation72 Strong coordination between clinical services and peer networks that promote prevention and encourage women to use services have been reported to be important programme elements associated with increased condom use and strong clinic attendance.Citation30Citation46

Provision of related health and social services valued by sex workers helps to improve programme credibility and strengthens prevention efforts.Citation 73 Sex workers have similar needs for reproductive health and other services as others, and can be expected to ask early for family planning and general medical care for themselves and their dependents.Citation 74 In addition, especially where sex worker HIV prevalence is already high, access to HIV testing and counselling, and HIV care and support services for sex workers and their families should be strengthened. Discussion of these and other operational issues are beyond the scope of this paper.

Discussion

A comprehensive approach to reducing STI transmission in commercial sex, with attention to important structural factors that increase risk and vulnerability, is a critical if often overlooked component of STI prevention and control.Citation 75 Such an approach can lead to large reductions in prevalence of common curable STIs and have immediate and long-term benefits for sex workers.

Effective preventive and curative STI services for sex workers are also key to control of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, in the larger community. STI control, by reducing HIV transmission efficiency when condoms are not used, is highly synergistic with other HIV prevention efforts. For such services to have maximum impact, they must:

| • | include strong peer education and empowerment components that support women to work collectively to address barriers to safer sex. | ||||

| • | emphasize consistent condom use as the only effective way to prevent HIV infection and other incurable viral STIs in sex work. | ||||

| • | provide effective treatment for both symptomatic and asymptomatic STIs. | ||||

| • | begin to address the larger social, legal, economic and human rights issues that increase vulnerability and risk. | ||||

There are limitations as well as benefits to STI control interventions. No one intervention is 100% effective at interrupting transmission. Synergistic combinations of interventions need to act at several levels to have maximum impact. Ideally, this would include a coordinated response to reduce vulnerability, stigma and discrimination, actively support 100% condom use in commercial sex, and improve access to effective STI prevention and care for sex workers and their clients. Presumptive treatment of sex workers, as an effective measure to rapidly reduce STI rates in high transmission areas, can strengthen STI prevention and control. Once prevalence rates are brought down, however, other longer-term strategies are essential to maintain reduced rates

It is important to recognize that curative modalities such as presumptive treatment are not effective against some important STIs, particularly viral infections such as herpes simplex virus (HSV-2), human papilloma virus (HPV) and HIV. Clinical staff and outreach workers should be aware that, without strong prevention efforts, sex workers may be drawn into a false sense of security that erodes rather than reinforces condom use. The limitations of presumptive treatment should always be explained to sex workers and the importance of maintaining consistent condom use emphasized by peer educators and clinic staff at every contact.

Further research to improve STI control and HIV prevention efforts in commercial sex networks should focus largely on operational issues to better define the optimal combination of preventive and curative services. Better methods are needed to reach clients and other vulnerable populations in areas where commercial sex takes place. Optimal intervals for screening or presumptive treatment have not been established and are likely to require adaptation to local epidemiologic and behavioural conditions. There is little experience with strategies for tapering or withdrawing periodic presumptive treatment as STI prevalence falls and condom use improves. Depending on the antibiotics used, control programmes should monitor STI and other important “bystander” pathogens for development of resistance. The role of HSV-2 in ongoing HIV transmission is increasingly recognized.Citation 76 Given the chronic nature of the infection and sub-clinical shedding, control measures are not clear but may include chronic suppressive therapy in some settings. Finally, evaluation of STI control efforts in commercial sex settings should be carried out where possible to measure impact on HIV incidence.

One of the biggest challenges in STI control and HIV prevention is how to scale up effective interventions to have sustainable impact. STI control and HIV prevention efforts should certainly be extended beyond easily identifiable groups of sex workers and clients, typically the domain of HIV/STI control programmes. Sex work is usually broader than its most obvious brothel or street-based forms—other types of transactional sex can be extensive and largely hidden. Appropriate prevention and treatment should be available to vulnerable populations living in areas where commercial sex takes place.

Reproductive health services have a role to play in supporting STI control efforts.Citation 77 Targetted interventions to reduce STI/HIV transmission in commercial sex should be seen as part of a larger effort to improve the reproductive health of communities. It should be recognized, and strongly advocated for, that improving preventive and curative services for sex workers and their clients results in fewer infections and fewer complications for all.

Acknowledgements

This paper was funded in part by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through FHI's Implementing AIDS Prevention and Care (IMPACT) Project (Cooperative Agreement HRN-A-00-97-00017-00). The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of FHI or USAID.

References

- CS Mgone, ME Passey, J Anang. Human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in two major cities in Papua New Guinea. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 29(5): 2002; 265–270.

- K Ford, DN Wirawan, BD Reed. The Bali STD/AIDS study: evaluation of an intervention for sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 29: 2002; 50–58.

- T Wi, V Mesola, R Manalastas. Syndromic approach to detection of gonococcal and chlamydial infections among female sex workers in two Philippines cities. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 74(Suppl.): 1998; S118–S122.

- A van den Hoek, F Yuliang, NH Dukers. High prevalence of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases among sex workers in China: potential for fast spread of HIV. AIDS. 15(6): 2001; 753–759.

- MR Joesoef, M Linnan, Y Barakbah. Patterns of sexually transmitted diseases in female sex workers in Surabaya, Indonesia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 8(9): 1997; 576–580.

- K Limpakarnjanarat, TD Mastro, S Saisorn. HIV-1 and other sexually transmitted infection in a cohort of female sex workers in Chiang Rai, Thailand. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 75: 1999; 30–35.

- VK Desai, JK Kosambiya, HG Thakor. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and performance of STI syndromes against aetiological diagnosis, in female sex workers of red light area in Surat, India. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 79: 2003; 111–115.

- M Rahman, A Alam, K Nessa. Etiology of sexually transmitted infections among street-based female sex workers in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 38: 2000; 1244–1246.

- Ramos ER, Wi T, Steen R, et al. Rapid and sustainable reductions in curable STDs among urban sex workers in the Philippines. Abstract TuOrD1152. XIV International Conference on AIDS, Barcelona, Spain, 6–10 July 2002.

- CA Ryan, OV Vathiny, PM Gorbach. Explosive spread of HIV-1 and sexually transmitted diseases in Cambodia. Lancet. 35: 1998; 1175.

- Leng HB, Wantha SS, Saidel T, et al. Success of Cambodian HIV prevention efforts confirmed by low prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and declining HIV and risk behaviors. Abstract. XIV International Conference on AIDS, Barcelona, Spain, 6–10 July, 2002.

- HIV Sentinel Surveillance and STI Periodic Prevalence Survey. National Committee for the Control of AIDS Bureau, Lao PDR, 2001.

- M Miyazaki, S Takagi, M Kato. Prevalence of and risk factors for sexually transmitted diseases among Japanese female commercial sex workers in middle- and high-class soaplands in Japan. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 13: 2002; 833–838.

- S Sarkar, N Islam, F Durandin. Low HIV and high STD among commercial sex workers in a brothel in Bangladesh: scope for prevention of larger epidemic. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 9(1): 1998; 45–47.

- SC Davis, B Otto, S Partohudoyo. Sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Kupang, Indonesia: searching for a screening algorithm to detect cervical gonococcal and chlamydial infections. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 30(9): 1998; 671–679.

- D Mulanga-Kabeya, E Morel, D Patrel. Prevalence and risk assessment for sexually transmitted infections in pregnant women and female sex workers in Mali: is syndromic approach suitable for screening?. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 75: 1999; 358–359.

- K Fonck, R Kaul, J Kimani. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of monthly azithromycin prophylaxis to prevent sexually transmitted infections and HIV-1 in Kenyan sex workers: study design and baseline findings. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 11: 2000; 804–811.

- NJ Simonson, FA Plummer, EN Ngugi. HIV infection among lower socio-economic strata prostitutes in Nairobi. AIDS. 4: 1990; 139–144.

- B Vuylsteke, V Ettiègne-Traoré, C Anoma. Assessment of the validity of and adherence to sexually transmitted infection algorithms at a female sex worker clinic in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 30: 2003; 284–291.

- PD Ghys, MO Diallo, V Ettiegne-Traore. Increase in condom use and decline in HIV and sexually transmitted diseases among female sex workers in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, 1991–1998. AIDS. 16(2): 2002; 251–258.

- FM Behets, JR Rasolofomanana, K Van Damme. Evidence-based treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infections developed with and for female sex workers. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 8: 2003; 251–258.

- L Mukenge-Tshibaka, M Alary, CM Lowndes. Syndromic versus laboratory-based diagnosis of cervical infections among female sex workers in Benin: implications of nonattendance for return visits. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 29: 2002; 324–330.

- M Alary, L Mukenge-Tshibaka, F Bernier. Decline in the prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases among female sex workers in Cotonou, Benin, 1993–1999. AIDS. 16(3): 2002; 463–470.

- S Lankoandé, N Meda, L Sangaré. Prevalence and risk of HIV infection among female sex workers in Burkina Faso. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 9: 1998; 146–150.

- I Ndoye, S Mboup, A. De Schryver. Diagnosis of sexually transmitted infections in female prostitutes in Dakar, Senegal. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 74(Suppl.): 1998; S112–S117.

- G Deceuninck, C Asamoah-Adu, N Khonde. Improvement of clinical algorithms for the diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis by the use of gram-stained smears among female sex workers in Accra, Ghana. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 27: 2000; 401–403.

- Behavioral and Biologic Surveillance Survey, Female Sex Workers, Round 1. Tropical Disease Research Center/National AIDS Council, Ministry of Health, Zambia/Family Health International, 1999.

- G Ramjee, SS Abdool Karim, AW Sturn. Sexually transmitted infections among sex workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 25: 1998; 346–349.

- MP Hawken, RDJ Melis, DT Ngombo. Part-time female sex workers in a suburban community in Kenya: a vulnerable hidden population. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 78: 2002; 271–273.

- R Steen, B Vuylsteke, T DeCoito. Evidence of declining STD prevalence in a South African mining community following a core-group intervention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 27(1): 2000; 1–8.

- KA Ryan, L Zekeng, RE Roddy. Prevalence and prediction of sexually transmitted diseases among sex workers in Cameroon. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 9(7): 1998; 403–407.

- Evaluation of Selected Reproductive Health Infections in Various Egyptian Population Groups in Greater Cairo, 1998–2000. Cairo: Ministry of Health and Family Health International, 2002.

- J Sánchez, PE Campos, B Courtois. Prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in female sex workers: prospective evaluation of condom promotion and strengthened STD services. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 30: 2003; 273–279.

- J Sánchez, E Gotuzzo, J Escamilla. Sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers: reduced by condom use but not by a limited period examination program. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 25: 1998; 82–89.

- WC Levine, R Revollo, V Kaune. Decline in sexually transmitted disease prevalence in female Bolivian sex workers: impact of an HIV prevention project. AIDS. 12(14): 1998; 1899–1906.

- F Uribe-Salas, CJ Conde-Glez, L Juárez-Figueroa. Sociodemographic dynamics and sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers at the Mexican–Guatemalan border. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 30: 2003; 266–271.

- Promoting 100 per cent condom use in Dominican sex establishments. 2001; Horizons Research Summary, Population Council: Washington DC.

- Khromova YY, Safarova EA, Dubovskaya LK, et al. High rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), HIV and risky behaviors among female detainees in Moscow, Russia. Abstract ThPeC7600. XIV International Conference on AIDS, Barcelona, Spain 6–10 July 2002.

- UNAIDS. Second generation surveillance for HIV: the next decade. WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC/2000.5 and UNAIDS/00.03E. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO, 2000.

- SN Tabrizi, S Skov, V Chandeying. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among clients of female commercial sex workers in Thailand. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 27(6): 2000; 358–362.

- RJ Hayes, KF Schulz, FA Plummer. The cofactor effect of genital ulcers on the per-exposure risk of HIV transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene. 98(1): 1995; 1–8.

- DW Cameron, JN Simonsen, LJ D'Costa. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 2(8660): 1989; 403–407.

- N O'Farrell. Targeted interventions required against genital ulcers in African countries worst affected by HIV infection. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 79(6): 2001; 569–577.

- Overs C. Sex workers: part of the solution. An analysis of HIV prevention programming to prevent HIV transmission during commercial sex in developing countries. Unpublished report, 2002.

- AM Brandt. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880. 1987; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- M Laga, M Alary, N Nzila. Condom promotion, sexually transmitted diseases treatment, and declining incidence of HIV-1 infection in female Zairian sex workers. Lancet. 344: 1994; 246–248.

- TM Rehle, T Saidel, SE Hassig. AVERT: a user-friendly model to estimate the impact of HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention interventions on HIV transmission. AIDS. 12(Suppl.2): 1998; S27–S35.

- S Moses, FA Plummer, EN Ngugi. Controlling HIV in Africa: effectiveness and cost of an intervention in a high-frequency STD transmitter core group. AIDS. 5(4): 1991; 407–411.

- RS Hanenberg, W Rojanapithayakorn, P Kunasol. Impact of Thailand's HIV-control programme as indicated by the decline of sexually transmitted diseases. Lancet. 344: 1994; 243–245.

- DD Celentano, KE Nelson, CM Lyles. Decreasing incidence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in young Thai men: evidence for success of the HIV/AIDS control and prevention program. AIDS. 12(5): 1998; F29–F36.

- Moses S, Ngugi EN, Costigan A, et al. Declining sexually transmitted disease and HIV prevalences among antenatal and family planning clinic attenders in Nairobi, Kenya, from 1992–1999. Abstract ThOrC727. XIII International Conference on AIDS, Durban, 9–15 July 2000.

- PD Ghys, MO Diallo, V Ettiegne-Traore. Effect of interventions to control sexually transmitted disease on the incidence of HIV infection in female sex workers. AIDS. 15(11): 2001; 1421–1431.

- M Alary, L Mukenge-Tshibaka, F Bernier. Decline in the prevalence of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases among female sex workers in Cotonou, Benin, 1993–1999. AIDS. 16(3): 2002; 463–470.

- GA Dallabetta, AC Gerbase, KK Holmes. Problems, solutions, and challenges in syndromic management of sexually transmitted diseases. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 74(Suppl. 1): 1998; S1–S11.

- N Meda, I Ndoye, S M'Boup. Low and stable HIV infection rates in Senegal: natural course of the epidemic or evidence for success of prevention?. AIDS. 13(11): 1999; 1397–1405.

- S Moses, EN Ngugi, A Costigan, C Kariuki, I Maclean, RC Brunham. Response of a sexually transmitted infection epidemic to a treatment and prevention programme in Nairobi, Kenya. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 78(Suppl. 1): 2002; 114–120.

- MO Diallo, PD Ghys, B Vuylsteke. Evaluation of simple diagnostic algorithms for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis cervical infections in female sex workers in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 74(Suppl. 1): 1998; S106–S111.

- RC Brunham, FA Plummer. A general model of sexually transmitted disease epidemiology and its implications for control. Medical Clinics of North America. 74(6): 1990; 1339–1352.

- P Rao, FY Mohamedali, M Temmerman. Systematic analysis of STD control: an operational model. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 74(Suppl. 1): 1998; S17–S22.

- M Over, P Piot. HIV infection and sexually transmitted diseases. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 1993; Oxford University Press: New York.

- R Steen, G Dallabetta. The use of epidemiologic mass treatment and syndrome management for sexually transmitted disease control. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 26(4/Suppl.): 1999; S12–S22.

- KK Holmes, DW Johnson, PA Kvale. Impact of a gonorrhea control program, including selective mass treatment, in female sex workers. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 174(Suppl.2): 1996; S230–S239.

- H Jaffe, D Rice, R Voigt. Selective mass treatment in a venereal disease control program. American Journal of Public Health. 69: 1979; 1181–1182.

- C Blackmore, K Limpakarnjanarat, J Rigau-Perez. An outbreak of chancroid in Orange County, California: descriptive epidemiology and disease control measures. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 151: 1985; 840–844.

- PG Jessamine, RC Brunham. Rapid control of a chancroid outbreak: implications for Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 142(10): 1990; 1081–1085.

- D Mugrditchian, G Dallabetta, P Lamptey. Innovative approaches to STD control. G Dallabetta, M Laga, P Lamptey. Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Handbook for STD Managers. 1996; AIDSCAP/Family Health International: Arlington VA.

- Olivier E, DeCoito T, Ralepeli S, et al. Maintenance of STD control in a mining community following introduction of a targeted intervention. In: Abstracts, International Society for STD Research, Berlin, 2001.

- ML Rekart, DL Patrick, B Chakraborty. Targeted mass treatment for syphilis with oral azithromycin. Lancet. 361: 2003; 313–314.

- Steen R, Olivier E, Mzaidume Z, et al. Periodic presumptive treatment as a component of a comprehensive HIV/STD prevention programme in a South Africa mining community. In: Abstracts, International Society for STD Research, Berlin, 2001.

- R. Steen, E. Olivier, Z. Mzaidume, et al. STD declines in a South African mining community following addition of periodic presumptive treatment to a community HIV prevention project. XIV International Conference on AIDS, Barcelona, 6-10 July 2002.

- S Jana, S Singh. Beyond medical model of STD intervention–lessons from Sonagachi. Indian Journal of Public Health. 39(3): 1995; 125–131.

- FM Behets, JR Rasolofomanana, K Van Damme. Evidence-based treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted infections developed with and for female sex workers. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 8(3): 2003; 251–258.

- B Vuylsteke, S Jana. Reducing HIV risk in sex workers, their clients and partners. P Lamptey, D Gayle. HIV/AIDS Prevention and Care in Resource-Constrained Settings: A Handbook for the Design and Management of Programs. 2001; Family Health International: Arlington, VA.

- T Delvaux, F Crabbé, S Seng. The need for family planning and safe abortion services among women sex workers seeking STI care in Cambodia. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 88–95.

- S Day, H Ward. Sex workers and the control of sexually transmitted disease. Genitourinary Medicine. 73(3): 1997; 161–168.

- World Health Organization. Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2: Programmatic and Research Priorities in Developing Countries. Report of a WHO/UNAIDS/LSHTM Workshop. WHO/HIV_AIDS/2001.01. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

- M Berer. Integration of sexual and reproductive health services: a health sector priority. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 6–15.