Abstract

In communities where early age of childbearing is common and HIV prevalence is high, adolescents may place themselves at risk of HIV because positive or ambivalent attitudes towards pregnancy reduce their motivation to abstain from sex, have sex less often or use condoms. In this study, we analyse cross-sectional survey data from KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, to explore whether an association exists between the desire for pregnancy and perceptions of HIV risk among 1,426 adolescents in 110 local communities. Our findings suggest that some adolescents, girls more than boys, were more concerned about a pregnancy if they lived in environments where youth were perceived to be at high risk of HIV infection. The probability that pregnancy was considered a problem by boys was positively correlated with the proportion of adult community members who thought youth were at risk of acquiring HIV, and for girls by the proportion of peers in the community who thought youth were at risk of HIV. We also found that becoming pregnant would be a bigger problem for the African girls than the white and Indian girls. The analysis suggests that for some adolescents, in addition to effects on educational and employment opportunities, the danger of HIV infection is becoming part of the calculus of the desirability of a pregnancy.

Résumé

Dans les communautés où les grossesses précoces sont fréquentes et où la prévalence du VIH est élevée, les adolescents peuvent être à risque du VIH car des attitudes positives ou ambivalentes à l’égard de la grossesse réduisent leur volonté de s’abstenir d’avoir des relations sexuelles, d’avoir moins de relations ou d’utiliser des préservatifs. Dans cette étude, nous analysons les données d’une enquête transversale à KwaZulu Natal, Afrique du Sud, afin de déterminer si le désir de grossesse était associé à la perception du risque de VIH chez 1.426 adolescents d’une centaine de communautés. Certains adolescents, filles plus que garçons et jeunes garçons plus que leurs aı̂nés, craignaient davantage une grossesse s’ils vivaient dans un environnement jugeant les jeunes à haut risque de contracter l’infection à VIH. De même, la probabilité que la grossesse soit considérée comme un problème par les garçons était corrélée positivement avec la proportion de membres adultes de la communauté qui pensaient que les jeunes risquaient de contracter le VIH, et pour les filles avec la proportion de leurs pairs dans la communauté qui jugeaient que les jeunes étaient à risque du VIH. Nous avons aussi découvert qu’une grossesse était plus problématique pour les filles africaines que pour les jeunes blanches et métis. L’analyse suggère que, outre les conséquences sur l’éducation et l’emploi, certains adolescents tiennent compte du risque d’infection à VIH quand ils calculent la désidérabilité d’une grossesse.

Resumen

En comunidades donde es común tener hijos a una edad temprana y la prevalencia de VIH es alta, los adolescentes puedan exponerse a VIH porque sus actitudes positivas o ambivalentes hacia el embarazo reducen su motivación de abstener de sexo, tener relaciones sexuales con menos frecuencia o usar condones. En este estudio analizamos datos de una encuesta transversal de KwaZulu Natal, Sudáfrica, para explorar si existe una asociación entre el deseo de un embarazo y percepciones de riesgo de VIH entre 1426 adolescentes en unas 100 comunidades locales. Nuestros resultados sugieren que algunos adolescentes–las mujeres más que los varones, y los varones menores más que los mayores–se preocupaban más por un embarazo si vivı́an en ambientes donde habı́a una percepción de alto riesgo de infección con VIH entre los jóvenes. De manera semejante, la probabilidad de que los varones consideraran problemático un embarazo se relacionaba positivamente con la proporción de adultos en la comunidad que pensaban que los jóvenes estaban en peligro de adquirir VIH, y en el caso de las muchachas con la proporción de sus pares en la comunidad que pensaban que los jóvenes estaban en peligro de adquirir VIH. Descubrimos además que un embarazo serı́a más problemático para las muchachas africanas que para las muchachas blancas y hindúes. El análisis sugiere que además de calcular los efectos de un embarazo sobre sus oportunidades de estudiar y tener empleo, algunos adolescentes empiezan a tomar en cuenta el peligro de infección con VIH.

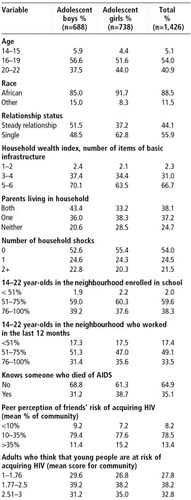

Table 2 Logistic regression model predicting proportion for whom a pregnancy would present a big problem among sexually active adolescents, KwaZulu Natal, South Africa, 1999

Patterns of adolescent childbearing and HIV infection are not independent of one another. Conditions and behaviours producing high levels of teenage pregnancy are also likely to bear upon the risk of acquiring HIV. This is borne out in sub-Saharan Africa, where some of the highest levels of adolescent childbearing occur in countries where HIV infection is most pervasive among the young. For example, in Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe, more than 40% of 20–24 year-olds have given birth by the age of 20, and more than 25% of 15–19 year-old girls attending antenatal clinics in the capital cities have HIV infection.Citation1Citation2 Although these statistics suggest a relationship between two daunting demographic trends, in social science and public health literature these phenomena are often considered distinct. Studies focus on the determinants of either HIV transmission or early pregnancy; few consider how (perceived) risk of HIV transmission might influence the desirability of pregnancy or vice versa.

Researchers in South Africa have coined the term “fertility conundrum” to capture the sense of conflict between either using condoms or abstaining from sex and the desire to become pregnant.Citation3 They argue that although this dilemma affects women in many settings, African women are particularly vulnerable because of the cultural emphasis on fertility. Furthermore, adolescents, because of rapid physiological and developmental changes, inexperience and a sense of invulnerability, may experience greater conflict than adults in considering the costs and benefits of pregnancy and risk reduction. This conflict may be exacerbated by inter-generational tensions around partner choice, sex, and condom or contraceptive use.Citation4 In communities where early childbearing is common and HIV prevalence is high, is there any evidence that adolescents who wish to delay childbearing are doing so because of the HIV risk environment? Using data collected among youth in 1999, we sought to answer this question in the case of adolescents in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa.

South Africa has high levels of teenage childbearing: about 30% of 20–24 year-old girls have given birth by the age of 20.Citation5 Moreover, youth in South Africa have been disproportionately affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Although having less than 1% of the world's 15–24 year-olds, South Africa accounts for roughly 15% of HIV infection globally in this age group.Citation6 Data from a population survey conducted in 2002 indicate that 9% of 15–24 year-olds nationally (12% of girls and 6% of boys) and 8% in KwaZulu Natal, the site for the present study, have HIV infection.Citation7 Among pregnant 15–19 year-old girls attending antenatal clinics, HIV prevalence escalated from 7% in 1994 to 22% in 1998 then fell to 15% in 2001.Citation8 Awareness of HIV/AIDS is widespread, with 95% of 15–19 year-old girls reporting that they had heard of the disease and 13% knowing someone with HIV or AIDS.Citation9

Reproductive decision-making and HIV in Africa

Numerous studies have documented lower fertility rates among populations of HIV-infected women in sub-Saharan Africa.Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15 Many focus on the biological mechanisms that reduce fertility among HIV-infected women: secondary amenorrhoea, fetal wastage and accelerated disease progression associated with pregnancy and/or co-infection with other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Increasingly, however, research has also revealed behavioural links to lower fertility. People may avoid pregnancy so as not to have a child that might be orphaned.Citation16 Death, unemployment or divorce in the wake of HIV infection may have important economic or psychological consequences that affect the desirability of pregnancy. Sexual intercourse may not occur as often as a result of divorce, illness or death.Citation17Citation18 Studies in Burkina Faso and Zambia revealed a widely held belief that all children born to HIV-positive women are infected with AIDS from their mothers and die, and that if diagnosed as HIV-positive, a woman should not become pregnant.Citation16Citation19 To date, however, no studies have isolated deliberate fertility control among women living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa as a behavioural cause of lower fertility. Interventions with HIV-positive women in Africa have not been found to motivate a significant change in reproductive outcomes. Couples have appeared cognisant of HIV risk and reported changes in family planning behaviour, yet fertility levels have not been greatly affected.Citation20Citation21Citation22 In studies in Zambia and Côte d'Ivoire, when asked if the risk of HIV had changed the way people in their community thought about the number of children they would like to have or when, respondents were perplexed about how HIV would affect these decisions unless the person knew they were infected.Citation16Citation23

A number of factors may contribute to this lack of deliberate fertility limitation. In the absence of HIV testing, pregnancy has been used to demonstrate absence of infection and continuing good health. An upsurge in pregnancies in Kampala in 1989–90 was explained locally as due to the belief that if a newborn child survived for one year, the mother was free of HIV.Citation24 Women frequently say that underlying the motivation to demonstrate good health and hide their HIV status is the fear of abandonment and rejection by spouse, family and community.Citation22Citation25Citation26 Contraception may not be accessible or affordable, especially among women at high risk of HIV infection, e.g. sex workers or adolescent girls engaged in cross-generational sex.Citation27 Finally, regardless of their own desires, for many women the decision whether to have sex or to have another child is made by someone else.Citation28Citation29

Context of teenage sexual activity in South Africa

Early childbearing in South Africa has been the norm for many decades and has produced, if not an expectation, at least an acceptance of teenage childbearing.Citation30Citation31Citation32Citation33 However, recent evidence suggests this norm is changing as fertility among adolescents declined by about 35% between the late 1980s and late 1990s.Citation9 In a study of young people from three metropolitan areas, RichterCitation34 reports that the majority wish to delay childbearing at least until completion of their schooling or until they have the means to provide for a child. Of the 12% of 16–19 year-old girls who wanted to have a child within two years, most said they wanted to prove fertility. Focus group participants in Khutsong township said that loss of educational and economic opportunities were reasons why, as teenagers, they had avoided rather than welcomed pregnancy.Citation35 According to the 1998 South African Demographic and Health Survey (SADHS), 33% of adolescents had been pregnant by the time they reached age 20, but only 20% of births to adolescents in the three years before the survey were reported as wanted.Citation9

Although the majority of adolescents may not wish to become pregnant soon, they are nonetheless under a great deal of peer pressure to have a boyfriend or girlfriend, and for boys especially, to have many partners. Sexual activity with a partner confers the status of a relationship, and for girls may bring benefits in the form of gifts or financial support. For boys, having many girlfriends can be an affirmation of manhood.Citation33Citation36Citation37 As a result, sexual activity is common among South African adolescents.Citation34Citation38 The SADHS found that 38% of unmarried 15–19 year-old girls and 71% of unmarried 20–24 year-old women had at least one sexual partner in the 12 months before the survey.Citation9

The high rate of HIV infection among the young indicates that much sexual activity is unprotected by condoms. Nationally, about half of sexually active 15–24 year-old women use injectables as a method of contraception, while 21% of 15–19 year-old and 19% of 20–24 year-old unmarried women used a condom the last time they had sex with their regular partner. Even lower proportions used condoms with spouses or casual partners.Citation9 Recent figures show high levels of awareness of HIV/AIDS for the younger age groups, and uneven but still relatively high awareness of HIV prevention in both urban and rural settings.Citation39 However, even where knowledge of HIV/AIDS is high, ignorance about reproduction and fertility remains pervasive and formal sex education or life skills programmes may be introduced after adolescents are already sexually active and at risk.Citation40 Moreover, education and increased reproductive knowledge are not always sufficient for preventing early sexual activity or HIV transmission. For example, in focus groups, girls argued forcefully that sex education is a part of school and everyone who goes to school should be aware of the dangers of “having boyfriends”.Citation41Citation42 Nevertheless, skills for communicating and negotiating with partners are low or non-existent, especially among adolescent girls.Citation32Citation36Citation43Citation44 In addition, many first sexual experiences may have been coerced,Citation36Citation41Citation45 and violence may be related to condom use if condoms are seen to convey mistrust of a partner or a presumption of infidelity or uncleanliness.Citation33Citation37Citation44Citation46

Not all information about South African adolescents' sexual practices is discouraging, however. VargaCitation47 and Preston-WhyteCitation3Citation48 found that young men may be willing to use a condom with prostitutes, but not their wives, and MacPhail and CampbellCitation35 found positive views about condom use that could provide a foundation for peer education. KellyCitation49 reported that 22–79% of young people aged 17–24 in six sentinel rural and urban sites had used condoms the last time they had sex. A comparison of condom use across age groups in the 1998 SADHS shows higher levels of condom use among 15–19 year-olds (20%) than among 20–24 year-olds (14%) at last sexual intercourse, compared to 7% or less among other age groups.Citation9 The 2001 South African National HIV Prevalence, Behavioural Risks and Mass Media study provides further evidence of increasing condom use among adolescents, with 49% of 15–19 year-old girls reporting using a condom at last intercourse.Citation7 The 2001 study also suggests an increase in secondary abstinence with 14% of 15–24 year-old sexually experienced women reporting no sexual activity in the previous 12 months in 2002 compared with 9% in the 1998 SADHS. The drop in HIV infection rates among antenatal adolescents between 1998 and 2001 may partially be explained by these trends.

Data and methods

This paper uses data collected in 1999 from the first round of a longitudinal study of adolescents in KwaZulu Natal in South Africa entitled “Transitions to Adulthood in the Context of AIDS”.Citation38 KwaZulu Natal (KZN) is South Africa's largest province. Situated on the east coast, it has a population of 8.4 million and is about 45% urban. Africans, primarily Zulu-speaking, make up 76% of the KZN population, Indians 14%, whites 7% and 3% mixed race. According to antenatal prevalence data, KZN has the highest level of HIV infection in the country, with an estimated 36% of antenatal attendees HIV-positive in 2000.Citation50 National survey data from 2001 estimated prevalence among all adults in KZN to be 12%, attributed to widespread labour migration and its association with multiple partners, lack of condom use, the high value men place on multiple partnerships, high levels of poverty and poor health care services.Citation51

For this study, Durban Metro and Mtunzini Magisterial Districts were selected as representing urban, transitional and rural regions within KZN. We used a modified multi-stage cluster sample approach.Citation52 Information on the household composition, living conditions, recent shocks to the household and selected economic data were collected by means of an interview with the household head, current guardian or adolescent identified for the individual interview. Responding to pre-coded questions developed and pre-tested in KwaZulu Natal and administered by interviewers, adolescents aged 14–22 provided detailed education and work histories as well as information on sexual activity, reproductive preferences, contraceptive use and pregnancies. Data were also provided on perception of HIV/STI risk and stigma, and condom use and accessibility. The data collection teams were composed of men and women, and all interviews were conducted by interviewers of the same race and sex as the respondents.

Household interviews were conducted with 1,974 households in 110 enumeration areas. In these households, interviewers identified 3,770 adolescents aged 14–22 and completed individual interviews with 3,052 respondents. Community characteristics were assessed in an independent data collection effort in 110 of the 118 sampled enumeration areas. The perception of HIV risk and attitudes toward people with AIDS were measured using a street-intercept module, in which people living in the community were interviewed at central locations in the community, e.g. shopping centres, bus stops or busy streets. “Community” was defined by the administrative boundaries of the enumeration area. Interviewers talked with 40 respondents in most enumeration areas distributed evenly by sex and aged 14–30 or over 31. Responses in the street-intercept interviews were similar to those of the interviewed adolescents on questions of safety, crime and HIV risk perception.Citation53

The analysis was restricted to adolescents who had ever had sex because the issue of pregnancy in the near future had greater significance for this group than for others.Footnote* After all exclusions for data or methodological reasons, there were 1,426 adolescent respondents. Data from 98 enumeration areas were used to analyse boys' responses and 94 enumeration areas for girls' responses. The analysis is based on weighted data to control for clustering and non-response.

Outcome and explanatory variables

The main outcome measured was attitude towards a pregnancy in the near future, based on the following question: “In the next few weeks, if you discovered that you were pregnant, would that be a big problem, a small problem or no problem at all?” For boys the question was modified to begin: “If you discovered that your partner was pregnant…”. Although the extent to which pregnancy would be a big or small problem or no problem at all is not a measure of fertility, it does capture adolescents' fears and concerns regarding a pregnancy in their lives.

We also asked whether the respondent personally knew anyone who had died or who they thought had died of AIDS. Macintyre et alCitation18 found that personal experience of high levels of mortality from AIDS predicted behavioural change to reduce the risk of HIV infection among men in a three-country study in eastern and southern Africa. A second implication was that higher levels of disclosure or lower levels of denial of AIDS as a cause of death may affect behaviour.

A strong association exists within peer groups concerning sexual behaviour, e.g. the proportion who are sexually active, the rate of partner change and condom use.Citation54 Hence, the first measure of risk included in this analysis was the proportion of peer respondents in an enumeration area who believed that their friends were at risk of HIV infection. The second measure of risk was based on whether community members thought that young people in their community were at risk of acquiring HIV. Three responses—low, medium or high risk—were recorded. In our models, we do not include an individual measure of perception of risk because, using cross-sectional data, we are unable to tell the direction of influence on behaviour. For example, we cannot tell whether individual risk perception and protective behaviours such as condom or contraceptive use determine pregnancy preferences, or are outcomes of pregnancy preferences, or whether individual risk perception, risk behaviours and attitudes towards pregnancy are jointly determined by the same environmental and individual factors.Citation55 This analysis will be possible using longitudinal panel data in the future.Citation56

Additionally, we asked about aspects of the demographic, socio-economic and community context that might influence adolescents' calculation of the costs and benefits of pregnancy. These were selected on the basis of previous findings in the literature and exploratory analysis that suggested their importance for understanding attitudes towards pregnancy. These included age (14–15, 16–19, 20–22), race (African, white or Indian) and whether or not the respondent was involved in a current stable relationship with a spouse (1% of respondents were married) or a steady boyfriend or girlfriend. About 55% of respondents with a steady boy or girlfriend and 45% of single respondents reported having sex in the previous four weeks. This is not a measure of sexual activity but is included to capture whether the respondent was in a relationship likely to be socially sanctioned and lasting, and whether it might offer support for a baby.

Three further variables, derived from the household data, had been significant predictors of condom use and possibly attitudes towards pregnancy in this population in a previous analysis.Citation54 The first was a wealth index (based on roof type, wall type, toilet type, water source, electric supply and telephone ownership). The second was whether the household had both parents, or one or neither, living in the house, to measure the level of parental supervision of adolescents as well as household cohesion. The third was the number of “shocks” experienced in the household in the previous 12 months, whether unemployment, divorce, illness or death from any cause.

Finally, we measured the proportion of adolescents in the community enrolled in school and the proportion of young people who had worked for money in the previous 12 months by aggregating individual responses for each enumeration area, as conditions in communities, e.g. level of unemployment or crime can exert an influence on the choices young adults make.Citation57Citation58

Logit regression techniques were used to model the relationship between attitudes towards pregnancy and measures of risk perception. We estimated each model separately for boys and girls.

Results

The 1,426 sexually active adolescents were nearly evenly divided between boys and girls and most of them were aged 16 or older (Table 1). Nearly 90% were black South Africans, a majority (56%) were single, and most of those in a relationship reported their partner to be their boyfriend or girlfriend. Boys were more likely than girls to be in a relationship. One-third of the adolescents surveyed lived in households that lacked two or more items of basic infrastructure. Some 38% lived with both parents and 25% with neither parent. Boys were more likely than girls to live with both parents and in better-off households. Nearly half of the adolescents' households had experienced a significant shock in the previous year.

These adolescents were living in communities with substantial levels of school enrollment and work opportunities. Nearly all (98%) adolescents lived in communities where more than 50% of youth aged 14–22 were enrolled in school, and more than 33% lived in communities where 75–100% of adolescents aged 14–22 were currently attending school. Eighty-three per cent lived in communities where more than 50% of young people had earned money for work within the last 12 months.

One-third of the adolescents, more girls (39%) than boys (32%), knew someone who had died of AIDS. More than 75% of the adolescents lived in communities where 10–35% of youth said their friends were at risk of acquiring HIV. Fewer than 10% lived in communities where few adolescents thought their friends were at risk, and about 13% lived in communities where more than 33% of adolescents thought their friends were at risk. Not surprisingly, the cross-section of adults interviewed in the community perceived more risk for the young people in their communities than the adolescents themselves, who were inclined to underestimate their own vulnerability. Just over 25% of the adolescents lived in communities where a relatively small proportion of community members thought the young there were at risk of acquiring HIV, almost 40% lived in communities where around half of members perceived this risk, and 33% lived in communities where most members believed that the young were at risk of acquiring HIV.

The majority of boys and girls (74%) said a pregnancy in the next few weeks would be a big problem. Girls (78%) were more likely than boys (70%) to give this response, but the difference was not statistically significant. The results of the logistic regressions (Table 2) suggest that adolescent boys who wished to delay pregnancy were more concerned about their ability to support a child and how it would affect their opportunities for schooling, job training and personal development than about acquiring HIV. For example, boys younger than 20, who were more likely to be in school and less likely to be working than older boys, were more concerned about a pregnancy in the near future than older adolescents who may have completed school, those who were working and those able to support a child. White and Indian boys were more likely than African boys to view a pregnancy in the near future as a big problem, perhaps because these populations evince stronger social disapproval of early childbearing and typically experience higher opportunity costs of paternal responsibilities. This concern is somewhat attenuated when there are more household assets.

Attitudes towards the desirability of a pregnancy among young men were significantly associated with the extent to which community members thought adolescents were at high risk of acquiring HIV. A higher perception of risk within the community was associated with boys' increased desire to avoid a pregnancy in the near future and may be an indicator of the extent to which risky behaviours were practised. A significant association between this measure of risk and pregnancy preferences suggests that HIV is entering boys' calculus of the risk of unprotected sex and unintended pregnancy.

The results for girls were strikingly different. For them, age did not make a difference to preferences for timing of a pregnancy. Unlike the boys, the African girls were more than three times more likely than white or Indian girls to say that a pregnancy in the near future would be a big problem. Girls were particularly concerned about the impact on their education, with the proportion of 14–22 year-olds in their community enrolled in school being significantly associated with wanting to delay a pregnancy. The importance of material and emotional support was also shown; girls without a regular partner were more likely to perceive pregnancy as a problem than those with a partner.

Girls' preferences about the timing of a pregnancy were also significantly associated with their peer group's perceptions of risk—perhaps a proxy for their perception of their own personal risk. Young women who lived in communities where a high percentage of adolescents thought their friends were at high risk of acquiring HIV were significantly more likely to perceive that becoming pregnant in the near future would be a big problem than young women who lived in communities where peers perceived less risk to their friends. Young women seemed to be more sensitive to peer influences, whereas boys seemed to be more sensitive to adult influences in their community.

Discussion

Our research sought to determine whether South African adolescents' attitudes toward pregnancy were affected by the environment of risk of acquiring HIV. We found that educational and employment opportunities continue to affect attitudes towards pregnancy, but there was also evidence of the impact of the HIV pandemic. Some significant differences exist in perceptions of adolescent girls and boys, possibly because of the different consequences they experience as a result of pregnancy, or because their perceptions of the consequences of HIV risk in general differ.

The finding that becoming pregnant would be a bigger problem for African girls than for white and Indian girls refutes the suggestion put forth in previous research that babies born to young black South African girls are generally welcomed, and that the girls face few if any consequences.Citation30Citation32 Our results indicate that African girls are deeply concerned about becoming pregnant at an early age.

Although Macintyre et alCitation18 found a significant relationship among adult men between personal experience of high levels of mortality from AIDS and risk reduction behaviour elsewhere in Africa, we did not find an association among adolescents in our study between knowing someone who had died of AIDS and the wish to delay childbearing. This may be because the majority of adolescents did not know anyone who had died of AIDS and the rest did not seem to be aware of high levels of mortality from AIDS; this may be due to the stigma surrounding AIDS deaths, which still often remain hidden in the community. Hence, personal experience of AIDS may hold less relevance for adolescents compared with the attitudes and perceptions of neighbours and peers.

The analysis presented here is based on cross-sectional survey data and has several limitations. We do not account adequately for the significant socio-cultural differences among ethnic backgrounds and we used a crude measure of education (enrollment rates), which does not reflect either educational achievement or whether that education included a life skills curriculum, a major form of HIV prevention education in South Africa schools. Interpretation of the influence of the risk environment was almost certainly complicated by the fact that some of the adolescents in our sample knew their HIV status, whether positive or negative, which might have influenced their perception of the desirability of pregnancy. Finally, while we have carefully chosen community measures of HIV risk perception that we believe are exogenous to pregnancy preferences and reflect broader concerns, it is possible that the direction is reversed and perceptions in communities of risk may reflect young people's attitudes about pregnancy. Analysis of the longitudinal data, which will be available in the future from the Transitions study, will allow us to confirm or re-consider our findings.

Our analysis suggests that some adolescents, and girls more than boys, are more concerned about a pregnancy, which means having unprotected sex, if they live in environments where youth are perceived to be at high risk of HIV. Factors that have been identified in studies of adolescent childbearing conducted over the last 15 years continue to be important: the detrimental impact of a pregnancy on schooling and the increased financial and other responsibilities that follow the birth of a child. However, HIV risk also appears to be a factor in assessing the costs of a pregnancy. For all, the unprotected sex required for conception puts them at risk of HIV transmission. For girls, the double threat of pregnancy and HIV infection carries additional risks of disease transmission to the infant, and antenatal testing with possible disclosure of positive results and rejection.

In order to proceed safely with childbearing in the context of AIDS or to bolster their resolve to avoid an early pregnancy, adolescents need a realistic assessment of their HIV risk. Adolescents would benefit from HIV counselling and testing services that assist them to learn their own and their partner's HIV status and to make informed choices about pregnancy based on that knowledge, with the differing needs of boys and girls taken into account. Equally important is the reduction of the stigma surrounding HIV infection and the expansion of access to information, support and treatment for both adolescents and adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge our co-investigators for the “Transitions to Adulthood in the Context of HIV/AIDS” study, Julian May and Ntsiki Manzini, University of Natal, Durban and Stavros E Stavrou, DRA Development. Also Cathrien Alons Kehus, formerly with the Department of International Health and Development, and Tulane University, for assistance with data management and initial analysis. The study was supported by the Rockefeller Foundation and the US Agency for International Development through the Horizons Program, FOCUS on Young Adults Project and MEASURE/Evaluation project.

Notes

* Most respondents who reported ever having sex had been sexually active in the last year (88% of boys and 85% of girls); however, a much smaller proportion were sexually active in the month before the survey (54% of boys and 53% of girls). Some adolescents may not be having regular sexual relations for an extended period as a deliberate strategy to avoid pregnancy. A parallel analysis of adolescents who are not sexually active would be useful.

References

- S Singh. Adolescent childbearing in developing countries: a global review. Studies in Family Planning. 29(2): 1998; 117–136.

- US Bureau of the Census. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Data Base. 1999; Population Division, International Programs Center: Washington DCAt: 〈http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/hivaidsd.html〉

- E Preston-Whyte. Reproductive health and the condom dilemma: identifying situational barriers to HIV protection in South Africa. JC Caldwell. Resistances to Behavioural Change to Reduce HIV/AIDS in Predominantly Heterosexual Epidemics in Third World Countries. 1999; Health Transition Centre, National Center for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University: Canberra, 139–155. At: 〈http://nceph.anu.edu.au/htc/pdfs/resistances_ch13.pdf〉

- A Gage. Sexual activity and contraceptive use: the components of the decision-making process. Studies in Family Planning. 29(2): 1998; 154–166.

- Central Statistical Service. Census '96: Preliminary Estimates of the Size of the Population of South Africa. 1997; Central Statistics: Pretoria.

- UNICEF/UNAIDS/WHO. Young People and HIV/AIDS: Opportunity in Crisis. 2002; UNICEF: New York.

- Mandela Foundation and HSRC. South African National HIV Prevalence, Behavioural Risks and Mass Media: Household Survey 2002. 2003; Human Sciences Research Council: Cape Town.

- South Africa Department of Health. National HIV and Syphilis Sero-Prevalence Survey of Women Attending Public Antenatal Clinics in South Africa: Summary Report. 2002; SADOH: PretoriaAt: 〈http://www.doh.gov.za/aids/docs/syphilis.html〉

- South Africa Department of Health Medical Research Council/Macro International. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 1998, Preliminary Report. 1999; SADOH and MI: PretoriaAt: 〈http://www.mrc.ac.za/bod/dhsfin1.pdf〉

- RW Ryder, VL Batter, M Nsuami. Fertility rates in 238 HIV-1 seropositive women in Zaire followed for 3 years post-partum. AIDS. 5(12): 1991; 1521–1527.

- RM Kigadye, A Klokke, A Nicoll. Sentinel surveillance for HIV-1 among pregnant women in a developing country: 3 years' experience and comparison with a population serosurvey. AIDS. 9(6): 1993; 452–456.

- NK Sewankambo, MJ Wawer, RH Gray. Demographic impact of HIV infection in rural Rakai District in Uganda: results of a population-based cohort study. AIDS. 8(12): 1994; 1707–1713.

- RH Gray, MJ Wawer, D Serwadda. A population-based study of fertility in women with HIV-1 infection in Uganda. Lancet. 351(9096): 1998; 98–103. At: 〈http://pdf.thelancet.com/pdfdownload?uid=llan.351.9096.original_research.7867.1&x=x.pdf〉

- A Ross, D Morgan, R Lubega. Reduced fertility associated with HIV: the contribution of pre-existing subfertility. AIDS. 13(15): 1999; 2133–2141. At: 〈http://ipsapp006.lwwonline.com/content/getfile/13/1002/17/fulltext.pdf〉

- JR Glynn, A Buve, M Caraël. Decreased fertility among HIV-1-infected women attending antenatal clinics in three African cities. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 25(4): 2000; 345–352.

- N Rutenberg, A Biddlecom, F Kaona. Reproductive decision-making in the context of HIV/AIDS in Ndola, Zambia. International Family Planning Perspectives. 26(3): 2000; 124–130.

- S Gregson, T Zhuwau, RM Anderson. HIV and fertility change in rural Zimbabwe. Health Transition Review. 7(Suppl. 2): 1997; 89–112. At: 〈http://htc.anu.edu.au/pdfs/Gregson2.pdf〉

- K Macintyre, L Brown, S Sosler. “It is not what you know but who you knew”: relating behavior change to AIDS mortality in Africa. AIDS Prevention and Education. 13(1): 2001; 160–174.

- B Taverne. [Representations of mother to child transmission of AIDS: perception of risk and health information messages in Burkina Faso–in French]. Santé. 9(3): 1999; 195–199.

- M Temmerman, S Moses, D Kiragu. Impact of single session post-partum counseling of HIV infected women on their subsequent reproductive behavior. AIDS Care. 2(3): 1990; 247–252.

- M Kamenga, RW Ryder, M Jingu. Evidence of marked sexual behavior change associated with low HIV-1 seroconversion in 149 married couples with discordant HIV-1 serostatus: experience at an HIV counseling center in Zaire. AIDS. 5(1): 1991; 61–67.

- H Aka-Dago-Akribi, A Desgrées du Loû, P Msellati. Issues surrounding reproductive choice for women living with HIV in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(13): 1999; 20–29.

- A Desgrées du Loû, P Msellati, A Yao. Impaired fertility in HIV-1 infected pregnant women: a clinic based survey in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS. 13(4): 1999; 517–521.

- ME Ankrah. AIDS and the social side of health. Social Science and Medicine. 32(9): 1991; 967–980.

- Family Health International/AIDSCAP. AIDS in Kenya: Socioeconomic Impact and Policy Implications. 1996; FHI/AIDSCAP: Arlington, VAAt: 〈http://www.arcc.or.ke/nascop/aids.htm〉

- Maman S, Mbwambo J, Sweat M, et al. Intersections of HIV and violence: implications for HIV counseling and testing in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Paper presented at 11th International Conference on AIDS and STDs in Africa, Lusaka, 12–16 September 1999.

- N Luke. Age and economic asymmetries in the sexual relationships of adolescent girls in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning. 34(2): 2003; 67–86.

- R King, J Estey, S Allen. A family planning intervention to reduce vertical transmission of HIV in Rwanda. AIDS. 9(Suppl. 1): 1995; S45–S51.

- K Meursing, F Sibindi. Condoms, family planning and living with HIV in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 3(5): 1995; 56–67. At: 〈http://www.rhmjournal.org.uk/PDFs/05meursing.pdf〉

- E Preston-Whyte. Qualitative perspectives on fertility trends among African teenagers. WP Mostert, JM Lotter. South Africa's Demographic Future. 1990; Human Sciences Research Council: PretoriaAt: 〈http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/2200496.html〉

- E Preston-Whyte, M Zondi. Africa teenage pregnancy: whose problem?. S Burman, E Preston-Whyte. Questionable Issue: Illegitimacy in South Africa. 1992; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, 226–246.

- JC Caldwell, P Caldwell. The South African fertility decline. Population and Development Review. 19(2): 1993; 225–262.

- R Jewkes, C Vundule, F Maforah. Relationship dynamics and teenage pregnancy in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 52(5): 2001; 733–744.

- L Richter. A Survey of Reproductive Health Issues among Urban Black Youth in South Africa. 1996; Society for Family Health: Pretoria.

- C MacPhail, C Campbell. “I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things”: condom use among adolescents and young people in a Southern African township. Social Science and Medicine. 52(11): 2001; 1613–1627.

- CA Varga, L Makubalo. Sexual (non) negotiation. Agenda. 28: 1996; 31–38.

- CA Varga. Sexual decision-making and negotiation in the midst of AIDS: youth in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health Transition Review. 7(Suppl. 3): 1997; 45–67. At: 〈http://eprints.anu.edu.au/archive/00000964/00/Varga1.pdf〉

- N Rutenberg, C Kehus-Alons, L Brown. Transitions to Adulthood in the Context of AIDS in South Africa: Report of Wave I. 2001; Horizons Program: Washington DCAt: 〈http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/tasa.pdf〉

- E Jackson, A Harrison. Sexual myths around HIV/STDs and sexuality: the gap between awareness and understanding among rural South African youth. The African Population in the Twenty-First Century: Third Africa Population Conference, Durban, 6–10 December 1999. Vol 1: 1999; Union for African Population Studies and South African Department of Welfare: Durban, 153–171.

- N Manzini. Sexual initiation and childbearing among adolescent girls in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(17): 2001; 44–52.

- K Wood, R Jewkes. Violence, rape, and sexual coercion: everyday love in a South African township. Gender and Development. 5(2): 1997; 41–46.

- Kaufman C, de Wet T, Stadler J. Timing the alternatives: adolescent childbearing and transitions to adulthood in South Africa. Paper presented at Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, 23–25 March 2000.

- M Gready, B Klugman, E Boikanyo. South African women's experiences of contraception and contraceptive services. Beyond Acceptability: Users' Perspectives on Contraception. 1997; Reproductive Health Matters for the World Health Organization: London, 23–35. At: 〈http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/publications/beyond_acceptability_users_perspectives_on_contraception/gready.en.pdf〉

- A Harrison, N Xaba, P Kunene. Understanding safe sex: gender narratives of HIV and pregnancy prevention by rural South African school-going youth. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(17): 2001; 63–71.

- R Jewkes, L Penn-Kekana, J Levin. “He must give me money, he mustn't beat me”: Violence Against Women in Three South African Provinces. 1999; CERSA (Women's Health), South African Medical Research Council: PretoriaAt: 〈http://www.mrc.ac.za/researchreports/violence.pdf〉

- K Wood, J Maepa, R Jewkes. Adolescent sex and contraceptive experiences: perspectives of teenagers and clinic nurses in the Northern Province. 1998. Unpublished.

- CA Varga. South African young people's sexual dynamics: implications for behavioural responses to HIV/AIDS. JC Caldwell. Resistances to Behavioural Change to Reduce HIV/AIDS in Predominantly Heterosexual Epidemics in Third World Countries. 1999; Health Transition Centre, National Center for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University: Canberra, 13–34. At: 〈http://nceph.anu.edu.au/htc/pdfs/resistances_ch2.pdf〉

- E. Preston-Whyte. Gender and the lost generation: the dynamics of HIV transmission among black South African teenagers in KwaZulu Natal. Health Transition Review. 4(Suppl.): 1994; 241–255.

- K Kelly. Communicating for Action: A Contextual Evaluation of Youth Response to HIV/AIDS. Sentinel Site Monitoring and Evaluation Project, Stage One Report, Beyond Awareness Campaign. 2000; HIV/AIDS and STD Directorate, South Africa Department of Health: PretoriaAt: 〈http://www.cadre.org.za/pdf/Communicating%20for%20action.pdf〉

- AIDS Analysis Africa. 2000 sero-prevalence rates. AIDS Analysis Africa. 11(6): 2001; 3.

- Whiteside A. South Africa's 1998 survey shows no let-up. AIDS Analysis Africa 1999;10(1):1,10.

- AG Turner, RG Magnani, M Shuaib. A not quite as quick but much cleaner alternative to the expanded programme on immunization (EPI) cluster survey design. International Journal of Epidemiology. 25(1): 1996; 198–203.

- Brown L, Macintyre K, Stavrou S, et al. Measuring community effects on adolescent reproductive health in Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. Paper presented at Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Washington DC, 29–30 March 2001.

- Macintyre K, Rutenberg N, Brown L, et al. Social disorganization and condom use among adolescents in South Africa. Poster presentation at Population Association of America Annual Meeting, Washington DC, 29–31 March 2001.

- A Hermaline. Fertility regulation and its costs: a critical essay. RA Bulatao, RD Lee. Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries. 1983; Academic Press: New York, 1–53.

- Macintyre K, Rutenberg N, Brown L, et al. Understanding perceptions of HIV risk among adolescents in KwaZulu Natal. AIDS and Behavior. (forthcoming)

- D Kirby. Emerging Answers: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy. 2001; National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy: Washington DC.

- G Duncan, S Raudenbush. Assessing the effects of context in studies of child and youth development. Educational Psychologist. 34(1): 1999; 29–41.