Vulnerability, not just sex, responsible for high AIDS prevalence in Africa

Since the AIDS pandemic began, many scientists and sociologists have attempted to describe the epidemiology of the disease in terms of individual behaviour. This approach has been particularly used in efforts to understand and explain the rapid spread and high prevalence of the disease in sub-Saharan Africa, and has underpinned the international response to AIDS, heavily influencing public health policy and strategy, and affecting the design of prevention and care interventions at all levels. Action has concentrated on the individual, promoting safer sex, condom use and information about HIV/AIDS. However, despite some successes, there has been little impact on the incidence of disease. This relative failure might have been anticipated, as experience shows that public health problems need public health solutions.

HIV prevalence varies considerably in different countries, regions and populations. It is improbable that individual behaviour alone accounts for these variations and highly likely that other explanations exist. In industrialised nations, HIV prevalence rates are below 0.1% in the sexually active population, yet the poorest, most severely affected nations in sub-Saharan Africa have rates of 20–30% and above. If individual behaviour alone were responsible for this enormous variation, it would imply that people in some African countries have 250 to 2,500 times more unprotected/unsafe sex than people in Europe, the USA or Australia. Yet there is no evidence for anything like this level of extra unsafe sex in high prevalence areas. This paper argues that the difference is to do with vulnerability to infection.

It can be no coincidence that areas of highest HIV/AIDS prevalence are also the poorest regions of the world. Poverty leads to poor health status where inadequate public health means lack of clean water, appropriate sanitation and basic health services, and poor nutrition leads to an immune system unable to fight off infection. These conditions result in the diseases of poverty: diarrhoea, respiratory infections, tuberculosis, malaria and parasitic infections. In such an environment, biological vulnerability to HIV is also increased, yet poverty has been all but ignored as a determinant of high levels of HIV infection, in sharp contrast to well-proven public health approaches to other infectious diseases. Similarly, co-infection with other diseases of poverty has been neglected as a cause of susceptibility, infectiousness and higher rates of HIV transmission at the population level. An exception is the appreciation of the role of concomitant STIs, whose prevention and control is a key strategy in all national AIDS programmes.

Non-biological factors such as labour migration, prostitution, exchange of sex for survival and population movement for work or due to war and violence have received some attention, but the solutions proposed to these problems are again focused on individual behaviour rather than economic and political root causes. Thus, for example, migrant workers and sex workers are provided with condoms, but no policies are implemented to keep migrant labourers' families together.

A return to a basic needs approach to all the diseases of poverty in no way implies neglecting prevention and care interventions that improve or prolong life and reduce short-term risk. It does imply, however, that these actions must be positioned within a larger framework that addresses population vulnerability and environmental risk beyond the control of individuals, communities and even nation states in some cases.1

| 1. | Katz A. AIDS, individual behaviour and the unexplained remaining variation. African Journal of AIDS Research 2002;1(2):125–42. | ||||

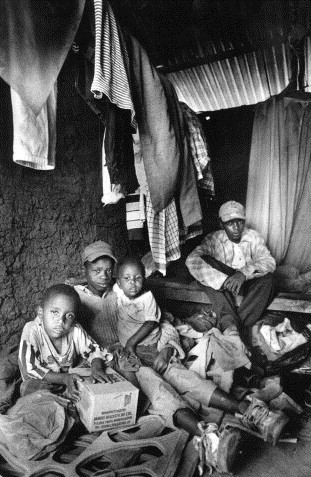

Number of AIDS orphans rapidly increasing in sub-Saharan Africa

In countries where HIV prevalence has remained low, there was little change in the numbers of orphans between 1992 and 1998, but in countries where HIV prevalence is high there has been a significant increase in the number of orphans. The proportion of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa under the age of 15 with one or both parents who have died varies from 5.5% in Niger and Mali to over 11% in Malawi, Zambia, Mozambique, Uganda and Zimbabwe. In general, paternal orphans are more common that maternal orphans, but orphans who have lost both parents (double orphans) are found disproportionately in countries most affected by HIV/AIDS. Tanzania, for example, has had an increase over a seven-year period from 71,100 to 174,400 double orphans and Zimbabwe over a five-year period from 33,800 to 94,400. Uganda is an exception, in that HIV prevalence has peaked and fallen but double orphan prevalence remains high. This can be explained by the early peaking of the HIV epidemic in Uganda, meaning that many HIV-infected parents have already reached the terminal stages of AIDS and died. This pattern will be repeated in other countries as their epidemics peak as well.

An analysis of poverty and orphans in selected countries showed some unexpected results. In the early 1990s levels of poverty for non-orphans and double orphans were similar in Niger, Ghana and Zimbabwe, but over the 5–7 year period between 1992 and 1998 whereas poverty increased for orphans in Ghana and Zimbabwe, it decreased for those in Niger. In comparison, orphans in Kenya and Tanzania were and have remained better off than their non-orphan counterparts. Being orphaned affects educational status adversely; orphans are less likely than non-orphans to be at their proper educational level, with a stronger effect at younger ages (6–10) than older ages (11–14). Loss of a mother is more detrimental to educational status than loss of a father, but loss of both parents is the most detrimental. An increasing number of orphans are being brought up in households headed by a grandparent, and in general it appears that orphans are being absorbed into their communities. However, the long-term consequences of the changing demographics in such communities have yet to emerge.1

| 1. | Bicego G, Rutstein S, Johnson K. Dimensions of the emerging orphan crisis in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science and Medicine 2003;56(6):1235–47. | ||||

Focusing HIV prevention on exposure

Despite considerable effort over the last 20 years, HIV/AIDS prevention programmes have met with limited success. One possible reason may be that such programmes have been designed using broad epidemiological indicators, grouping together countries that have similar overall prevalence of disease and using the same strategies for each group. A better approach might be to consider the dynamics of infection on a country-by-country basis, pinpointing where new infections are occurring, and whether and to what extent prevention policies are effecting change. Then, tailored programmes can be designed around the specific needs of each country and changed as necessary. For example, Kenya, Cambodia and Honduras can all be classified as having generalised epidemics with HIV prevalence of over 1% of the adult population. Yet recent data on new HIV infections in these countries clearly shows that whereas heterosexual sex with a partner is the most common form of infection for Cambodia, accounting for 58% of new infections, homosexual sex is most important in Honduras (40%) and sex work in Kenya (37%). Thus, prevention measures in these countries need to be different

Similarly, comparison of prevalence and incidence rates by type of exposure can also give useful information. In Indonesia, 40% of current prevalence is due to drug injection with shared unclean needles, but 80% of incidence, i.e. new infections, is acquired this way. In Cambodia over the last eight years, there has been a fall in incidence due to sex work from 70% to 23% but a rise in that due to heterosexual sex with a partner who had previously engaged in high-risk behaviour from 25% to 58%. Such analyses often show that in many countries it is the most marginalised and difficult to reach groups who are most at risk of infection and fuelling the continuing epidemic. This is a strong argument for a clearer focus on nationally and locally relevant policies and interventions.1

| 1. | Pisani E, Garnett GP, Grassly NC, et al. Back to basics in HIV prevention: focus on exposure. BMJ 2003;326(7403):1384–87. | ||||

Counting condoms

HIV/AIDS prevention campaigns have mostly centred on promoting condom use and reducing the number of sexual partners. However, because symptoms of HIV infection are slow to manifest, the effectiveness of such campaigns is difficult to measure over the short term. One possible indicator is changes in condom use. Surveys that rely on reported behaviour suffer from problems of recall and of provision of the “expected” or “good” response. However, they can provide useful information, particularly if the questions distinguish consistent, sporadic and never-use of condoms rather than only the most recent sexual contact. Data on condom sales, either from retail outlets or the manufacturers, can also give a guide. However, the former may be difficult to coordinate and the latter may not be available as “commercially sensitive” data. Nor do such data measure condom use; hence, techniques for checking for discarded condoms in hotels used by sex workers have also provided information, although use of such techniques is limited. Records relating to service provision by family planning clinics or health centres are a further source, but the social groups attending may change with time and condoms may become available from other sources. Additionally, surveys may not distinguish between the use of condoms for contraception or prevention of STIs, making it difficult to estimate the impact in terms of HIV/AIDS prevention. However, by using a combination of these methods rather than any single one, it is possible to make a reasonable estimate of the effect of education campaigns.1

| 1. | Goodrich J, Wellings K, McVey D. Using condom data to assess the impact of HIV/AIDS preventive interventions. Health Education Research 1998;13(2):267–74. | ||||

Women need to be taught how to put condoms on men too

This study looked at condom use errors when women put condoms on their male partners. Of 102 women aged 18–21 who had put condoms on their partners at least once in the previous three months, 51% put the condom on after starting sex and 15% took it off before sex was ended. Errors such as not leaving space at the tip (46%), putting the condom on wrong side up and needing to turn it over (30%), and not having a water-based lubricant available when required (15%) were reported. Breakage and/or slippage were reported by 28% of the women and 25% reported that their partners lost their erections in association with condom use. These data show the importance of teaching correct condom use to women as well as men.1

| 1. | Sanders SA, Graham CA, Yarber WL, et al. Condom use errors and problems among young women who put condoms on their male partners. Journal of the American Medical Women's Association 2003:58(20):95–98. | ||||

Condoms for adolescents cause uproar

The use of condoms for both contraception and protection against STIs is widely accepted in many parts of the world. Yet there is still discomfort and often considerable opposition to the idea of making condoms freely available and attractive to teenagers. In a protest against the low standard of sex education in Trinidad, a community outreach coordinator distributed condoms and sex education literature outside a school. This caused uproar amongst religious and other groups, but he defended his actions as a way of allowing young people to make choices.1 In Thailand, a new brand of scented condoms, named Sweet Teen and marketed with the slogan “Teen confidence”, is being labelled as a symbol of moral decay.2 Yet these and similar protests ignore the growing evidence that condom availability does not encourage more sex, but instead offers protection to those having sex, confirmed once more by recent research in US schools.3

| 1. | Inter Press Services. 3 June 2003. At:〈[email protected]〉. | ||||

| 2. | |||||

| 3. | Blake SM, Ledsky R, Goodenow C, et al, Condom availability programs in Massachusetts high schools: relationships with condom use and sexual behavior. American Journal of Public Health 2003;93(6):955–62. | ||||

Trends in sexual risk in Thailand

A study to assess trends in risk behaviours over a three-year period in Bangkok, using a repeated cross-sectional survey design and a structured questionnaire, collected five sets of self-reported sexual behaviour data on HIV-related risk during 1993–96 from direct and indirect women sex workers, men attending sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics, women attending antenatal clinics, male and female vocational students, and male and female factory workers. Reported patronage of commercial sex by the three groups of men declined by an overall average of 48% over the period. Other non-regular sexual partnerships declined among men attending STI clinic and vocational students. Condom use during most recent sexual intercourse between sex workers and clients peaked at high levels (>90%) in the early data waves, while among indirect sex workers and their clients, consistent condom usage increased from 56% to 89%. Low condom use persisted among sex workers and their non-paying sex partners. Single women reported low levels of sexual activity and condom use with no signs of increase. Similarly, married women attending antenatal clinics reported low condom use with their husbands, with no change in the study period. HIV sexual risk behavioural surveillance is a useful way of determining whether behaviour change is occurring in specific population groups. The results here confirm and add to evidence of risk reduction in Thailand. The behavioural changes did not occur uniformly but varied depending on the sexual dyad and the population group under study. Behavioural surveillance should be promoted and its methodologies strengthened in attempts to understand the local dynamics of HIV epidemics.1

| 1. | Mills S, Benjarattanaporn P, Bennett A, et al. HIV risk behavioral surveillance in Bangkok, Thailand: sexual behavior trends among eight population groups. AIDS 1997;11(Suppl.1):S43–S51. | ||||

Leaving sex work in Thailand

Despite attempts by the Thai government to slow the spread of HIV in the commercial sex industry, prevalence of HIV among female sex workers is still between 7 and 16%. This study of 42 current and former female sex workers investigated the factors which affect women's ability to leave sex work and influence their return to it. Over half of the women (25) had quit and re-entered sex work at least once, whereas 16 had quit and not re-entered although some would consider doing so if their circumstances altered. Four main factors were found to influence the decision to stay, leave or re-enter the sex industry: financial considerations, a relationship with a steady partner, attitude to sex work, and experience of HIV/AIDS. Of these, financial aspects were the strongest and most common factor. Needing money and not wanting to give up luxuries were reasons for staying, while accumulation of sufficient wealth or deciding to live a less luxurious life were reasons for leaving. Fear of HIV/AIDS seemed a factor only for those who had quit and not re-entered the work. Of the 17 women who were HIV-positive, some had quit in order to get more rest and live longer, whereas others chose to continue working as a way to earn a relatively large amount of money before becoming too sick to support their families. Three of the 17 had become infected after they left sex work and moved into a steady relationship, a phenomenon seen elsewhere. Interventions aimed at assisting women wanting to leave sex work will therefore need to address all these factors, first and foremost economic ones.1 The Thai National Economic and Social Development Board has recently proposed that the government legalises and taxes the sex trade in Thailand, because the large underground economy linked to the sex trade is depriving the government of much-needed tax revenue,2 a measure that could greatly affect the income of sex workers.

| 1. | Manopaiboon C, Bunnell RE, Kilmarx PH, et al. Leaving sex work: barriers, facilitating factors and consequences for female sex workers in northern Thailand. AIDS Care 2003;15(1):39–52. | ||||

| 2. | The Nation (Thailand). 14 February 2003. | ||||

Thailand's AIDS policies and programmes

Thailand has been hailed as having one of the few effective national AIDS prevention programmes. Perhaps the most important aspect has been the strong commitment shown at the political level, channelling a range of government and NGO activities via the Office of the Prime Minister and allocating significant resources and initiating a five-year plan, which emphasises community participation. Another key element is an inclusive approach, which not only considers the prevention of HIV but also encompasses care of the sick and efforts to reduce stigma and discrimination against those with infection. At the same time, a massive public information campaign has concentrated on prevention, behaviour change, condom use and AIDS as a social problem. A “100% Condom Programme” promotes the universal use of condoms in commercial sex, a particularly innovative approach given that prostitution is illegal in Thailand. A range of public health officials, brothel owners, local police and sex workers have collaborated to make sure the programme is adhered to. Additionally, some repressive policies, formulated as an early reaction to the AIDS epidemic, such as the mandatory reporting of details of AIDS patients, were withdrawn. That this multiple approach has worked is shown by a significant reduction in risk-related behaviour, STI consultations and new HIV infections.

Before the AIDS epidemic, Thailand already had an extensive network of STI services, a strong family planning programme, general acceptance of condom use, a health infrastructure with qualified staff and epidemiologists and a tradition of making decisions informed by data. Many of these are missing in countries severely affected by AIDS. It is clear that increasing condom use and decreased demand for commercial sex were key to the 80% drop in new infections seen. But the effects of the various elements which contributed to this outcome—police surveillance, STI checks for sex workers, free condoms, care of the sick and so on—have not been individually evaluated for effectiveness or cost. Indeed many of the costs were covered under other budgets, such as those for general health care and policing. The Thai strategy focused on commercial sex as the main conduit of HIV. This has resulted in current HIV transmission in Thailand being mainly restricted to other sectors of the population—wives of men infected some time ago, injecting drug users and unregistered, often illegally immigrant sex workers. The country now needs to show the same level of political will and commitment to reach these groups in the community.1

| 1. | Ainsworth M, Beyrer C, Soucat A. AIDS and public policy: the lessons and challenges of “success” in Thailand. Health Policy 2003;64:13–37. | ||||

Evidence of sexual risk reduction among South African youth

It is important not to misrepresent and over-elaborate risks related to teenage sexuality with statistics. In contemporary South Africa, for example, risk reduction is a more appropriate interpretation of trends in teenage sexual behaviour as a number of key indices show positive changes in safer sexual behaviour. When data from the 2002 Nelson Mandela/HSRC study on HIV prevalence, Behavioural Risks and Mass Media1 were compared with the 1998 Demographic and Health Survey it was found that secondary abstinence (previously sexually active, but no sex in the past year) had increased among girls aged 15–24. Among sexually active girls aged 15–19 condom use had increased in the same period from 19.5% to 48.9% and amongst women 20–24 from 14.4% to 47%. A large proportion of current South African teens have not yet been sexually active, and of those who have had sex before, significant proportions have used condoms at last sexual intercourse or have been abstinent. Over-elaboration of youth risk is problematic from a planning, policy and strategic point of view, and may result in inappropriate interventions.2

| 1. | HIV Prevalence, Behavioural Risks and Mass Media Study. Nelson Mandela/HSRC, 2002. Available at: 〈www.cadre.org.za〉. | ||||

| 2. | Parker W. Re: Adolescent behaviour in South African context of AIDS. At: gender-aids eForum 2003: 〈[email protected]〉. | ||||

Protecting babies from HIV in breastmilk

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV through breastmilk is well documented, accounting for somewhere between a quarter and a half of all pregnancy-related transmission. The risk of infection is calculated at 0.00064 per litre of breastmilk, equivalent to 0.00028 (approximately one in 4,000) per day of breastfeeding. This is similar to the calculated risk of heterosexual transmission per unprotected sex act in adults. The risk increases significantly if mothers are at an advanced stage of disease.1 Viral load is significantly higher in colostrum and early milk than in milk tested 14 days after delivery, and for every ten-fold increase in breastmilk viral load, there is a two-fold increased risk of transmission.2 Yet, alternatives for many HIV-infected mothers remain limited. Formula feeds may not be available, or clean water and the appropriate skills to reconstitute them may not exist. Additionally, formula feeding may be associated with the stigma of HIV, causing many mothers to reject this option. WHO recommends that HIV-infected mothers should be advised of feeding options in the light of local conditions. However, the absence of definitive guidelines has resulted in confusion between two conflicting messages: one that women should exclusively breastfeed for a maximum of six months and one that they should not breastfeed at all, but instead use formula feeds.

Now, new research has raised the possibility of safer breastfeeding for HIV-positive mothers. A small study in Uganda and Rwanda followed babies given one of two common AIDS drugs during a period of exclusive breastfeeding. Only 1% of these babies contracted HIV through breastmilk, a considerable reduction from the expected level of about 15%. This is an encouraging result, which could become part of a package of measures to stop MTCT. It has also been suggested that the same outcome could be achieved by treating the mothers, thereby reducing HIV viral loads in breastmilk.3

| 1. | John-Steward GC, Hughes JP, Nduati R, et al. Breast-milk infectivity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected mothers. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2003;187(5):741–47. | ||||

| 2. | Rousseau CM, Nduati RW, Richardson BA, et al. Longitudinal analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in breast milk and of its relationship to infant infection and maternal disease. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2003;187(5):736–40. | ||||

| 3. | Das P. Feeding risk cut for HIV-infected women. Lancet 2003;362(9380):300. | ||||

Reduced fertility in women with HIV infection in Tanzania

Recent studies in sub-Saharan Africa have shown that fertility is reduced among HIV-infected women compared with uninfected women. This paper examines the association between HIV and fertility among 4,139 women in Kisesa, in rural Tanzania, where HIV prevalence among adults is about 6%. The HIV-associated fertility reduction among women was investigated by estimating fertility rates by HIV status and HIV prevalence rates by fertility status. A substantial reduction (29%) was observed in fertility among HIV-infected women compared with HIV-uninfected women. The fertility reduction was most pronounced during the terminal stages of infection, but no clear association with duration of infection was observed. Use of modern contraception was higher among HIV-infected women. However, both among contracepting and non-contracepting women, a substantial reduction in fertility was seen among those with HIV. The reduced fertility could be due to behavioural differences such as less sexual contact, more frequent condom use and/or biological reasons.1

| 1. | Hunter SC, Isingo R, Boerma JT, et al. The association between HIV and fertility in a cohort study in rural Tanzania. Journal of Biosocial Science 2003;35(2):189–99. | ||||

HIV vaccines–no good news yet

The results of the first phase III trials of an HIV/AIDS vaccine (AIDSVAX B/B), carried out in the US, Canada, Puerto Rico and the Netherlands, have been disappointing. The AIDSVAX B/B vaccine uses two parts of the HIV subtype B gp120 protein. In contrast the vaccine undergoing phase III trials in Thailand uses bits from both subtype B and subtype E. About 20 other vaccines are in various stages of testing. Some use different principles such as viral vectors and DNA-based approaches, but the vast majority use the genes and proteins from the group B subtypes prevalent in North America, Europe, Australia, Japan and Puerto Rico. Very few consider the African and Asian subtypes A, C, D and E. Yet the possibility that each subtype may need its own vaccine is growing as a number of variations in the proteins of the various subtypes have been found.1–3

| 1. | VaxGen. VaxGen announces initial results of its phase III AIDS vaccine trial. Press release, 24 February 2003. At: 〈www.vaxgen.com/pressroom/index.html〉. | ||||

| 2. | Walgate R. AIDSVAX trial not the end of the story. Scientist At: 〈www.biomedcentral.com/news/20030228/06〉. | ||||

| 3. | Goulder PJ, Walker BD. HIV-1 superinfection—a word of caution. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;347(10):756–58. | ||||

Fathering a child when you're HIV positive

Although there is no indication that sperm (rather than semen as a whole) are infected with HIV, an HIV-positive man cannot father a child without the risk of infecting both his partner during unprotected sex and the child by subsequent mother-to-child transmission. However, the technique of “sperm-washing” has reduced this risk. Of 53 washed sperm samples used for insemination in a London hospital, none has shown evidence of residual HIV. Eighteen of the couples involved in this study have now conceived a child using this method. Research is also underway into other techniques, such as heating sperm to kill HIV, that will leave sperm activity intact.1

| 1. | “Sperm washing” hope for HIV patients. BBC News. 24 April 2003. At: 〈http://ww2.aegis.org/news/bbc/2003/BB030411.html〉. | ||||

Raising global awareness with the personal touch

A US broadcasting company, HBO, has made a five-part documentary series “Pandemic: Facing AIDS” which looks at the scope of the crisis using individual stories from around the world. Among the stories are those of a 27-year-old former sex worker from Thailand who was filmed during the final stages of her life; an Indian truck driver who revealed his illness to a village community that might ostracise him, and his pregnant, HIV-positive wife who ignored her family's objections to stay with her husband; and a Brazilian granted a reprieve on his deathbed by access to a free government programme providing comprehensive drug therapy. The series is accompanied by a multimedia campaign, including a website 〈www.pandemicfacingaids.org〉, teachers' guides, a music CD and a travelling art exhibition.1

| 1. | IPPF News. 17 June 2003 At: 〈[email protected]〉. | ||||

World AIDS campaign 2004 to focus on women

The World AIDS Campaign 2004 will focus on women for the first time since 1990. “Women, HIV and AIDS” will explore changes since 1990 and the challenges which arise as a new generation of girls matures, becomes sexually active and enters motherhood. Sessions on this theme are also planned for the July 2004 International AIDS Conference in Bangkok.1

| 1. | UNAIDS. World AIDS Campaign 2004 announcement. July 2003. | ||||