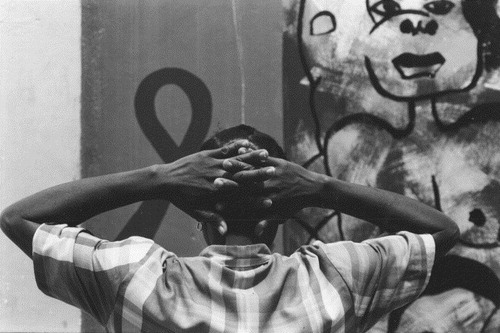

HIV has a myriad of effects on the sexual and reproductive health of both men and women, and sexual and reproductive health services are of central importance for those with HIV and AIDS. The aim of this issue of RHM is to raise awareness of the intersections between HIV/AIDS and sexual and reproductive health and rights and how these should be reflected in national policies and programmes.

In the 1990s, at the same time as the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action was being taken up by one country after another, HIV was being spread through unprotected sex around the globe. Given the increasingly sophisticated awareness of the connections between sex and reproduction, it seemed obvious that advocacy, health service provision, research and information on sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS would burgeon, and that these two areas of work would come closer together in every way. Yet what has happened on the ground has been far more limited. Why?

| • | Although leaders in the sexual and reproductive field and those working in HIV/AIDS came together to discuss joint programmes, they could not agree on ways forward because they had different and entrenched agendas. | ||||

| • | Responsibility and funding in national health systems for maternal and child health/family planning (MCH/FP) programmes on the one hand, and newer, vertical AIDS control programmes on the other, have been kept separate. | ||||

| • | Bilateral and multilateral donors have maintained separate departments for HIV/AIDS and for sexual and reproductive health (or family planning alone), and for the most part they fund programmes, projects and services in these areas separately. Even funding for condom provision has remained divided between family planning condoms and HIV prevention condoms. | ||||

| • | Work within and between the World Health Organization and UNAIDS to address the interlinkages between HIV/AIDS and sexual and reproductive health has been limited. Although UNAIDS has made its campaign theme for 2004 “Women and HIV”, the reproductive and sexual health needs and rights of women with HIV, apart from those related to gender-based violence, are unconscionably absent from the topics the campaign will address. | ||||

| • | The verticality of AIDS funding has been greatly exacerbated by the narrow remit of the Global Fund to Fights AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which so far has failed to recognise any linkages with sexual and reproductive health, even HIV-related anaemia, tuberculosis and malaria in pregnant HIV-positive women. | ||||

HIV and AIDS have been with us for more than two decades. One in every 100 adults of reproductive age in the world, including up to 40% of men and women in some African countries, is HIV infected.Citation1 Millions have died. Yet it has taken 20 years for the rich world to recognise the need for HIV prevention, treatment and care activities where they are most needed, “commensurate with the magnitude of the threat posed by the disease”.Citation2 Now, suddenly, following rapid shifts in political leadership, priority setting, power brokering and funding policies in international health and development circles, it is widely considered an unassailable fact that in the global “competition” for resources and attention, sexual and reproductive health has lesser priority and has lost out to AIDS, as if addressing the one had no connection with addressing the other. Overnight, SRH money has declined and AIDS money is being dumped from all sides on the worst-hit countries in such vast quantities that all other health and development programmes are being threatened. Ironically, there is probably no way most countries will be able to spend the money fast enough or show the sort of immediate impact that is being demanded of them in the absence of well-functioning public health systems and sexuality education programmes. Yet if countries are honest and say–as was said with maternal mortality in 1987 and with other sexual and reproductive health indicators in 1994 and 1999–that it will take at least 20 years to make a dent in the epidemic, will donor money still be there 20 years down the line? Or will short-term attention spans again undermine supposedly rock-solid commitments? some think the Global Fund is already dead in the water, for example. Will Bush get to win his war against SRH, too?

It is in this context that there has been a dearth of visible, in-depth mainstream attention to sexual and reproductive health and rights in relation to HIV/AIDS. Nonetheless, a number of serious attempts have been made to bring the two sets of issues together since the early 1990s. On the sexual and reproductive health side, some MCH/FP programmes have sought to integrate basic STI prevention, STI syndromic treatment and HIV testing and counselling into their service delivery. The limited way in which this has been carried out, however, and the lack of proper training and resources available to do it, have meant that such efforts have often failed to have an impact on STI or HIV transmission and have been rejected (undeservedly) as too difficult to implement. Although HIV challenges the widespread use of contraceptive methods that do not protect against STIs, however, family planning promotion messages often remain virtually unchanged even where HIV infection rates are high. Hence, many people are still more concerned about unwanted pregnancy than about HIV infection and risk.

On the HIV/AIDS side, prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV took centre stage after 1995 when effective treatment for preventing neonatal infection at delivery was developed. However, even though WHO/UNAIDS guidelines situate PMTCT interventions in antenatal, delivery and post-partum care and in family planning and abortion services, PMTCT initiatives have been developed primarily as paediatric interventions and have addressed HIV-positive women's needs only peripherally if at all.

These initial efforts offer many lessons for future work: they have not yet gone far enough nor have they yet received the kind of support and resources that would sustain them to do so in the longer term. Moving forward, however, has been hampered by a limited understanding of the contribution that sexual and reproductive health programmes can make to HIV/AIDS control and vice versa. Until recently, most journals in the two fields have stayed out of each other's territory most of the time. Similarly, many in the sexual and reproductive health field rarely, if ever, read an AIDS journal or attend a meeting where HIV is the main subject (or didn't until AIDS money beckoned them). Many HIV specialists are similarly remiss when it comes to reproductive (and even sexual) health. Researchers in the two fields often do not consult or reference one another's articles even when addressing a topic of relevance to both. Papers on sexual and reproductive health topics submitted to international AIDS conferences rarely achieve plenary status, but rather are tucked away on posters and the conference CD. A serious meeting of the minds is long overdue, but both groups have 20 years of catching up to do on information produced and experience gained on the other side of the fence, to avoid reinventing the wheel.

HIV/AIDS in sexual and reproductive health services

The sexual and reproductive health and rights issues of importance to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment include:

| • | access to HIV counselling and testing through all sexual and reproductive health services and referral to sexual and reproductive health services through HIV counselling and testing and HIV antiretroviral treatment centres; | ||||

| • | family planning and STI services that promote condoms as a primary form of contraception and stress the importance of dual protection for women and men who wish to avoid both pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection, including those who are HIV-positive; | ||||

| • | family planning and safe abortion services that address the needs of HIV-positive women as well as those of the general population of women, e.g. advising women at risk of HIV/STIs against IUD use; | ||||

| • | sexual and reproductive health services for single adolescents, migrant and refugee women, injection drug users and sex workers, most of whom have not been considered important target groups for these services; | ||||

| • | antenatal, delivery and post-partum care that includes attention to the specific needs of HIV-positive pregnant women and their infants; | ||||

| • | specialist care for gynaecological and obstetric complications for HIV-positive women as well as for the wider population of women, to reduce AIDS-related maternal mortality and morbidity; | ||||

| • | safe blood supplies to prevent HIV infection in women and infants during transfusions in cases of severe anaemia and haemorrhage; | ||||

| • | prevention of HIV transmission from HIV-positive pregnant women to their infants, as well as antiretroviral treatment for pregnant and post-partum women, mothers and fathers, in order to keep them alive and well to raise their children, as well as to support safe breastfeeding; | ||||

| • | prevention, screening and treatment for reproductive tract infections (RTIs) and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in the population of reproductive age, presumptive STI treatment for those at high risk of HIV and community-based treatment for communities at high risk, which will help to reduce not only HIV infection, but also secondary infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease and negative pregnancy outcomes arising from untreated RTIs/STIs in women; | ||||

| • | screening and treatment for cervical cancer, which is an AIDS-defining condition (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) in HIV-positive women,who are at risk at younger ages than HIV-negative women; | ||||

| • | screening and treatment for malaria and TB,especially in pregnant women, and for the multiple causes of anaemia, with particular attention to HIV-positive women; | ||||

| • | sex education and promotion of safer sexual relationships and sexual health, particularly among adolescents, to reduce the incidence of STIs and HIV infection in the longer term; | ||||

| • | attention to menstrual disorders and problems of low fertility, which can be particularly difficult to resolve in HIV-positive women; | ||||

| • | services for survivors of rape and sexual assault that include antiretroviral post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV, STI screening and treatment, emergency contraception and abortion services. | ||||

Sexual and reproductive health issues in HIV/AIDS services

Antiretroviral treatment and other HIV-related medical interventions have transformed women's experience of pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding, yet AIDS treatment centres do not prepare women for these changes or take account of their need for information and support in this regard. Furhermore, AIDS treatment centres rarely provide or refer HIV-positive women for contraception or abortion services, or even recognise that men and women whom they identify as at risk of HIV/STIs, such as injecting drug users or sex workers, may need a broader range of sexual and reproductive health care. HIV-positive men, meanwhile, are often not seen as fathers with children or as having needs of their own for information and support in this regard by AIDS referral centres. Furthermore, the fact that adolescent girls and women with HIV may have different treatment needs from men (e.g. following sexual abuse or sexual assault) has so far barely surfaced in many developing countries with a high burden of HIV disease. Alternative perspectives on access to treatment, such as what will happen if HIV-positive women are offered antiretroviral treatment (e.g. in their role as mothers or teachers or health workers) but not their husbands, are only beginning to be recognised and addressed.

At the same time as access to treatment is taking centre stage, it is apparently getting more difficult to raise finds for HIV prevention. Even condom promotion is being marginalised and sidelined. Care-related issues are also being neglected, such as the need to provide support for grandparents who are looking after the millions of AIDS orphans whose parents did not have access to anti-HIV treatment and who died at very young ages. Thus, a better balance of attention to the range of issues urgently needs to be established.

Resolving problematic macro sexual and macro socio-economic conditions

The epidemics of HIV and other STIs are first and foremost an infectious disease emergency,Citation1 arising from a context of problematic macro sexual and macro socio-economic conditions which affect both women and men. In the past five years or so, however, a particular form of feminist gender analysis related to HIV transmission has emerged, consisting of assertions that women are more vulnerable to HIV than men, that women are powerless and greater victims of HIV than men, and that women are more at risk of HIV biologically because they are women. As if AIDS were only a gender power issue. As if 50% of adults with AIDS were not men, and in some countries and regions a far greater proportion than 50%. As if men only had sex with women. As if the vagina were the only route of sexual infection and not also the anus and the mouth. As if women were always faithful and men never. As if men were almost never infected by women and not just the other way around. As if men with AIDS were less likely to become ill and die without treatment than women with AIDS.

This distorted and distorting gender analysis fails to confront the role of sexuality and the diversity and meanings of sexual relations and, perversely, helps to maintain gender stereotypes. Worse, it has developed alongside a growing obsession with individual sexual behaviour change as the only solution to the epidemic, a right-wing dismissal of most sexual relations as illicit and therefore not deserving of protection, and the denigration of condoms as symbols of illicit sex rather than as a safe and highly effective means of dual protection.

As part of that same gender analysis, higher levels of infection in 15–24 year-old girls than in boys the same age in some settings are cited as evidence of young women's greater vulnerability, without reference to the fact that in the over-25 age group in those same settings, due to sexual networking patterns, more young men than women are infected. The vulnerability picture, however, is more complex. While women are indeed biologically more at risk of HIV in any one act of heterosexual vaginal sex than their male partners, all other things being equal, “other things” are often not equal and not all sex is vaginal or heterosexual. Apart from sex workers, men generally have more sex and more partners, male as well as female, than women. The more partners they have, any of whom might be infected, and the more unprotected sex they have, the more at risk of infection they are. If they or their partner(s) also have an STI, their risk of infection increases correspondingly. That is why so many men are at high risk of infection with HIV and STIs, and only then why they more often infect their women partners.

Even now, there is an absence of debate and discussion, except in very small circles, of what is happening in sexual relationships that makes both men and women vulnerable to HIV and STIs in epidemic proportions, and why at this point in history so much more sexual intercourse is protected against unwanted pregnancy than against sexually transmitted infections. Understanding of sexual behaviour and of community influences on it, including the overweaning influence of stigma, remains superficial. Studies with the same unhelpful data on knowledge, attitudes and practices as 10–15 years ago (“knows about AIDS”, “didn't use a condom”) are still being published, while those with new insights are few and far between. Yet differences in perceptions of sexual risk between men and women are a legitimate subject for gender analysis, as are the thorny issues of disclosure of HIV status, partner notification, and the willful transmission of HIV and how to confront it, all of which get very little attention.

The role of macro socio-economic conditions in fostering unsafe sexual relationships also deserves greater attention, given the absence of government policy and efforts to control the epidemic by reducing the causes of socio-economic vulnerability. These include the lack of decently paid work for the great majority of women in most developing countries, especially the poorest; employment and migration policies that force large numbers of men and women to migrate for work leaving behind their spouses and families; and tourism and drug dealing that are tied to the sex industry. These widespread phenomena all support the commercialisation and commodification of sex, the proliferation of trading and selling sex for money and goods, and of multiple partnering, casual sex and frequent partner change. Reducing these conditions would be far more effective in promoting sexual health at a population level than only trying to change the sexual behaviour of millions of individuals one by one by one

Integrating some services, adding and strengthening others and expanding outreach

The papers in this issue of RHM discuss sexual and reproductive health interventions, activities and perspectives whose aim is to “interrupt HIV transmission, mitigate the epidemic's clinical and social effect, reduce stigma and vulnerability, and promote the rights and welfare of HIV-infected and uninfected people.”Citation1 They address the role of gender and of sexual relations in the epidemic, the importance of alliances between gay and feminist activists, the role of responsibility and agency in relation to disease prevention, the invisibility of AIDS in reproductive health programmes, mode of delivery and post-partum sterilisation for HIV-positive women, the right of HIV-positive men as well as women to love and found a family, the inappropriateness of training traditional birth attendants to provide HIV-related information and care, the importance of a health and human rights framework in understanding and reducing vulnerability, the association between perception of HIV risk and the desire for pregnancy, views on re-use of female condoms, the value of focusing on protection of fertility to promote dual protection, and the experience of HIV-positive women in these matters. It also includes two in-depth reviews, one on screening and presumptive treatment for STIs in sex workers, and the other on the contribution to date of sexual and reproductive health services to the fight against HIV/AIDS. Excerpts from a book containing the insights of a committed Ugandan AIDS activist affected by HIV are also included.

These papers all show that it is to the detriment of both sexual and reproductive health care and HIV/AIDS control if each continues to be treated as a vertical programme with little interaction. They show that integrated approaches to sexual and reproductive health care, HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care, and sexuality and health education should be further developed, based both in the clinic and in the community. This will involve integrating some services, adding and strengthening others, expanding outreach to new population groups and creating well-functioning referral links to optimise outreach and impact. An example of the latter is referral of both women and men for AIDS treatment as part of antenatal PMTCT counselling. Better indicators for joint programmes, ones that do not focus narrowly on vertical objectives, would also contribute to these efforts, e.g. clinic protocols for HIV testing and counselling that include discussion with couples about safer sex-whether the test result is negative or positive-along with the offer of access to condoms, STI care, contraception, abortion and antenatal and delivery services.

More than ten years ago, national short-, medium-and long-term plans for AIDS control were called for by the former WHO Global Programme on AIDS. Countries with a generalised HIV and STI epidemic need different programme plans from those with a low or high prevalence of STIs and a low prevalence of HIV. Those with high maternal mortality and morbidity rates, high cervical cancer prevalence, low contraceptive use, unsafe blood supplies, large sex industries or high rates of injection drug use need to factor these in to their planning as well. A modelling exercise on interventions to reduce HIV incidence in Botswana and India found that promoting condom use by women sex workers with their clients would have the greatest single impact on the epidemic in India, whereas in Botswana, with a highly generalised epidemic, STI management seemed to be the most effective single intervention.Citation3 For AIDS programmes looking for somewhere to start, such modelling exercises could be useful. At the same time, all countries need to continue to develop and improve their sexual and reproductive health services, and should do so partly by addressing how these intersect with HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care.

Together, the papers in this issue of RHM provide a sharper focus on what programmes and services should be trying to achieve when they commit themselves to promoting sexual and reproductive health and defeating HIV/AIDS across the world. They challenge UNAIDS, WHO, UNFPA, national governments, NGOs, the women's health movement and perhaps most provocatively donors to take these matters more fully on board.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the participants of the RHM workshop on these issues at the International AIDS Conference in Barcelona, July 2002.

References

- G Pison. Tous les pays du monde (2003). Population & Sociétés. 2003; 392.

- KM De Cock, D Mbori-Ngacha, E Marum. Shadow on the continent: public health and HIV/AIDS in Africa in the 21st century. Lancet. 360: 2002; 67–72. 6 July.

- NJ Nagelkerke, P Jha, SJ de Vlas. Modelling HIV/AIDS epidemics in Botswana and India: impact of interventions to prevent transmission. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 80(2): 2002; 89–96.