Abstract

The global prevalence of genital prolapse is estimated to be 2–20% in women under age 45. In Nepal, genital prolapse appears to be widespread, but little published evidence exists to buttress this claim. This paper presents findings of two studies, one ethnographic and one clinic-based, in western Nepal. The ethnographic study involved 16 focus group discussions with 120 community members and key informants, and covered community perceptions and women's experience of prolapse and its perceived causes and consequences. The clinic-based study was conducted among 2,072 women who presented with gynaecological complaints and received a diagnosis. One in four of them had genital prolapse, of whom 95% had self-reported the prolapse. The most commonly perceived causes of prolapse were lifting heavy loads, including in the post-partum period. The adverse effects reported included difficulty urinating, abdominal pain, backache, painful intercourse, burning upon urination, white watery discharge, foul-smelling discharge, itching, and difficulty lifting, sitting, walking and standing. The results confirm prolapse as a significant public health problem in western Nepal. We strongly recommend developing systematic, rotational gynaecological clinics in rural districts, the use of a screening checklist and counselling for prevention and early management of genital prolapse by district health workers for family planning and antenatal patients.

Résumé

On estime que 2 à 20 % des femmes de moins de 45 ans présentent un prolapsus génital. Au Népal, le prolapsus semble très répandu, mais peu de données le confirment. Deux études ont été menées au Népal occidental. L'étude ethnographique a analysé les perceptions communautaires et les témoignages de femmes sur le prolapsus, ses causes et ses conséquences, au cours de 16 discussions de groupe avec 120 membres de la communauté et informateurs clés. L'étude clinique a porté sur 2 072 femmes qui souffraient des troubles gynécologiques et avaient bénéficié d'un diagnostic. Une femme sur quatre avait un prolapsus génital, et 95 % d'entre elles l'avaient signalé elles-mêmes; elles l'attribuaient au fait d'avoir soulevé de lourdes charges, notamment après l'accouchement. Les symptômes indiqués comprenaient des difficultés de miction, des douleurs abdominales, des maux de dos, des rapports sexuels douloureux, des brûlures après avoir uriné, des pertes blanches, des pertes nauséabondes, des démangeaisons et des difficultés pour soulever des poids, s'asseoir, marcher et se tenir debout. Les résultats ont confirmé que le prolapsus était un grave problème de santé publique au Népal occidental. Nous recommandons la création de consultations gynécologiques dans les districts ruraux, et l'utilisation par les agents de santé de listes de contrôle et d'information pour le dépistage et le traitement précoce du prolapsus auprès des patientes des centres de planification familiale et de soins prénatals.

Resumen

Se calcula que la prevalencia global de prolapso genital en mujeres menores de 45 años es de 2 a 20%. En Nepal, el prolapso genital parece ser común, pero existen pocos datos publicados que lo prueban. Este artı́culo presenta los resultados de dos estudios, uno etnográfico y otro clı́nico, en Nepal occidental. Para el estudio etnográfico se realizaron 16 grupos focales con 120 miembros de la comunidad e informantes claves. Abarcaron las percepciones que tenı́a la comunidad y las experiencias de las mujeres con prolapso, y sus causas y consecuencias percibidas. En el estudio clı́nico participaron 2,072 mujeres que se presentaron con malestares ginecológicos y recibieron un diagnóstico. Una de cada cuatro tenı́a prolapso genital, que fue autoreportado por un 95% de las afectadas. La causa percibida más común fue el alzar cargas pesadas, incluyendo durante el perı́odo posparto. Los efectos adversos reportados incluyeron dificultad para orinar, dolor abdominal, dolor de espalda, dolor durante el coito, ardor al orinar, flujo blanco y acuoso, flujo maloliente, picazón, y dificultad para alzar, sentarse, caminar y estar de pie. Los resultados confirman que el prolapso es un problema de salud pública significativo en Nepal occidental. Recomendamos establecer clı́nicas ginecológicas sistemá ticas y rotativas en los distritos rurales, el uso de una lista de despistaje, y consejerı́a para la prevención y manejo temprano de prolapso genital impartida por los trabajadores de salud a nivel de distrito con clientes de planificación familiar y atención prenatal.

According to World Health Organization estimates, reproductive ill-health accounts for 33% of the total disease burden in women globally. The global prevalence of genital prolapse is estimated to be 2–20% in women under age 45.Citation1 In Nepal, a recent surge in studies has boosted information on women's reproductive health, including on nutrition in pregnancyCitation2, Citation3 contraception,Citation4, Citation5 infertilityCitation6 and maternal mortality and morbidity Citation7 Citation8 Citation9. However, but data on reproductive morbidity remain inadequateCitation1 in spite of widespread reports of problems, particularly genital prolapse in rural hill areas.

Genital prolapse, sometimes also called pelvic organ prolapse, occurs when a weakened pelvic musculature can no longer support the proper positioning of the pelvic organs, most commonly the vagina and uterus. Uterine prolapse is classified into three categories: first degree, when the cervix appears at the vaginal opening only while the woman is bearing down; second degree, which is defined by the cervix descending to the vulva; and third degree, which occurs when the cervix protrudes beyond the vaginal canal and the entire uterus may extend beyond the vulva. Uterine prolapse is often accompanied by prolapse of the rectum (rectocele) and/or bladder (cystocele) into the vaginal wall. The exact aetiology is unknown, but contributory causes include multiparity, excess intra-abdominal pressure, tissue atrophy secondary to ageing and oestrogen loss, joint hypermobility and congenital ligament weakness. Citation10 Citation11 Citation12

Prevalence data for prolapse are scattered at best. In a 2002 study in the United States, 27,342 women were evaluated in the Women's Health Initiative.Citation13 14.2% of the 16,616 women who had a uterus were diagnosed with genital prolapse. Another US study suggests that genital prolapse is present in some 20% of post-menopausal women.Citation14 In a 1993 study from Egypt, physician diagnosis found that 56% of 509 ever-married women between the ages of 14 and 60 had prolapse.Citation15 In 1997, 694 parous non-pregnant women in Istanbul were examined and 27% were diagnosed with severe “pelvic relaxation”.Citation16 In a 1997 study in southern India, 440 women under the age of 35 were evaluated for gynaecological morbidity, and cases of prolapse were noted in 3.4%.Citation17 In a 2000 study in northern India, of 2,990 married women surveyed for prolapse, cases were diagnosed in 7.6%.Citation18

Difficulties arise when studying gynaecological morbidity because of the sensitive nature of the genital area. Researchers therefore often use self-report as a data-gathering mechanism. Although the reliability of self-report is debated generally, a study conducted in 2000 in Tamil Nadu, India, found that of 37 women who self-reported prolapse, 32 were diagnosed with the condition,Citation19 which suggests a high correlation between self-reported and diagnosed prolapse.

Age at onset of prolapse is also an issue. It was commonly thought that most cases occur post-menopausally, but mounting evidence suggests that in some countries and cultures, prolapse occurs at much younger ages. For example, the women in the Tamil Nadu studyCitation19 were aged 15–50, and the mean age at which women first developed symptoms was 26.2. Many of them had suffered from the condition for more than ten years (mean 12.3 years). Ten of the women indicated that they had developed symptoms after their first delivery, three after their second delivery, 11 after their third delivery, nine after their fourth to sixth delivery, and two after their ninth delivery. When asked about the perceived causes of their prolapse, 18 of the 32 women mentioned heavy manual labour following delivery. Other perceived causes included difficult labour, accidents, first birth at a young age, frequent childbearing and surgery.

The problems arising from prolapse can drastically affect quality of life. Prolapse causes difficulty walking, sitting, lifting and squatting. Lower back pain, abdominal pain, painful intercourse and difficulty urinating and defecating are also documented. Women often complain of “something falling out” or “a heaviness” in the genital area. Citation8 Citation19 Citation20 Citation21 Citation22 Citation23

Relatively scant documentation about genital prolapse exists in Nepal. In the 1970s a physician in a mission hospital in western Nepal noted that prolapse was “a condition that causes untold misery to thousands of women and therefore deserves study of methods, of treatment and, if possible, prevention”.Citation20 Of the 1,500 cases that she examined, nearly all presented as second and third degree prolapse. As in the Tamil Nadu study,Citation19 a large percentage of the women were young, with 10% below the age of 20. In 1997, data were collected in a health camp in Jumla, a remote region in mid-western Nepal. Among the 720 gynaecological patients seen, 17% were diagnosed with prolapse.Citation21

A 1997 hospital-based study from the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu investigated the risk factors, beliefs, treatment and care practices of women with prolapse.Citation22 Of the 1,147 gynaecological patients attending the hospital during the study period, 110 (9.6%) were found to have prolapse. The most significant factors associated with the onset of prolapse were heavy work (94.5%), and lifting heavy weights during the post-partum period. The great majority (72.7%) of the women developed prolapse before menopause and 23.7% were 15–25 years old at onset. Similar findings were documented in a community-based reproductive morbidity study commissioned by UNFPA in 1999.Citation24 Of the 431 women who participated, prolapse was diagnosed in 12% of cases.

This paper presents findings from two studies on genital prolapse, one ethnographic and one clinic-based, whose aim was to confirm anecdotal information on prolapse in Western Nepal. The ethnographic study was undertaken in 2000 in three districts in mid- and far-western Nepal to obtain information about community perceptions and women's experience of prolapse. The clinic-based study, carried out in 2001 in two of the same districts, sought to obtain proxy indicators on the prevalence of prolapse and record perceived causes and associated factors of prolapse in women who presented at two gynaecological clinics.

The far-western hilly region is one of the more remote regions of Nepal. National studies comparing regions consistently note less development and poorer health in this region.Citation3, Citation4 In 1998 the Nepal Micronutrient Status Survey found a 50–59% prevalence of anaemia among women in the region. The same survey also noted 35–39% of women were underweight, 5.9% were stunted and 20–29% were thin (body mass index less than 18.5).Citation3 The 2002 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey reported similar data from the far-western hilly region, with 10.8% of women measuring less than 1.45m in height and 27.7% of women as thin.Citation4

Methodology

In the ethnographic study, the researcher visited Bardiya, Doti and Achham districts in mid- and far-western Nepal in conjunction with the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ) Reproductive Health Project. In each district, focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted as well as individual interviews with key informants. Convenience sampling was used for all participants. FGD participants were married men and women aged 18–80. Men were included in the study in order to achieve a community perspective. Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, FGDs were all men or all women, although both sexes were asked the same questions. A total of 120 people participated in 16 FGDs. Key informants were either female health care workers (6) or women self-identified as having prolapsed uterus (24). Key informant questions were similar to those of the FGDs, but more time was allotted for case studies. The topics discussed included common health problems, pregnancy customs, women's daily activities, causes of prolapse, impact of prolapse, and treatment. Interviewee responses were organised into categories which, based on repetition and frequency, were then analysed for themes.

The findings of the ethnographic study revealed such a high perceived prevalence of prolapse that one year later a clinic-based study was carried out as part of an intervention in which district-level female health care workers were trained in diagnosing and managing prolapse by gynaecologists, and subsequently helped provide, under the supervision of a gynaecologist, clinical services to women attending gynaecological clinics. The temporary clinics were held in the district hospitals of Achham and Doti, both within the far-western region of Nepal, in February and March 2001. Bardiya district was not included because the local government was reluctant to endorse the temporary clinic. The study sought to elicit the magnitude and disease patterns of prolapse and other reproductive morbidities among women seeking reproductive health services. Specifically, it sought to identify the extent and types of reproductive morbidity, the associated physical and social conditions and the underlying socio-cultural aspects and related traditions. While the focus was on prolapse, other conditions examined included infertility, sexually transmitted and other reproductive tract infections and menstrual disorders (not reported here).

The clinic-based study population consisted of women 12 years of age and older, including pregnant women, who presented with gynaecological complaints. Women reporting non-gynaecological complaints were treated but excluded from the study. A total of 3,820 women came to the gynaecological clinics; of these, 2,705 were identified as gynaecological patients, of whom 2,702 received a diagnosis after a physical examination.

A questionnaire was used to gather general socio-demographic information. An additional questionnaire was used with women complaining of infertility and genital prolapse. Both had been field tested for consistency and comprehension at the Maternity Hospital in Kathmandu. The patient history form had questions on obstetric history, gynaecological morbidity and other complaints. The physical examination and laboratory results were also recorded. All the data were entered into the computer via FOX Pro. SPSS was used to compile the data and complete the necessary analysis. Beyond basic frequency tables, means and medians, the Chi square test was used to elicit significant relationships between various data fields. The Pearson's Test was also utilised to analyse the relationship between different variables.

Frequency and type of genital prolapse and traditional treatments tried

Of the 24 women self-identified as having prolapse in the ethnographic study, 11 were aged 20–29, seven were 30–39, three were aged 40–49 and three were 50 or older. Ten of the women reported that prolapse had occurred after their first birth.

One in four of the women presenting to the two gynaecological clinics complained of prolapse. Of the 2,072 patients who received a diagnosis, 518 (25.1%) were identified with some type of genital prolapse. Analysis showed that 95.1% of the Achhami women and 98.3% of the Doti women self-reporting prolapse were clinically diagnosed with the condition, with an equal number of cases having first, second and third degree prolapse, a finding which mirrors earlier studies from Nepal.Citation20, Citation22

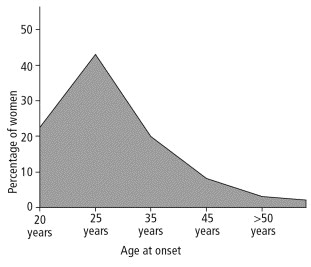

The mean age of onset of prolapse among women attending the clinics was 27 and the median was 24 (see FootnoteFigure 1 ). The mean number of years suffering from prolapse was ten. 37.5% of the women reported only one completed pregnancy at the onset of prolapse, 18.3% had completed two pregnancies and 2.3% were nulliparous.

Labour and delivery are most commonly supervised by mothers-in-law or elderly village women (sudeni); only 7.1% of the women reported assistance from a trained health care worker at their last delivery. 87.0% reported having no rest prior to the birth of their last child. For the post-partum period, 22.6% stayed in a goth Footnote* outside the home according to local tradition. 21.0% reported resting seven days or less after their last delivery before resuming work.

Approximately one in four women reported trying traditional remedies for the prolapse, which included ingesting special herbs or foods, hanging upside down, or inserting an alcohol and herb-soaked cloth into the vagina–all on a regular basis, often weekly. Traditional remedies also included visiting traditional healers, who conducted special ceremonies to ward off illness and sudenis. Often the sudeni would prescribe the herbs and special foods and sometimes instruct the woman how to insert pessaries of alcohol and herbs. More than half the women with prolapse reported that their mothers had also suffered from the condition and 23.1% that their sisters also had prolapse.

Perceived causes of genital prolapse

The 492 women self-reporting prolapse in the gynaecological clinic were asked what they thought had caused their condition. Two specific themes emerged: lifting heavy loads and a lack of post-partum rest. Previous studies have suggested that an increase in intra-abdominal pressure may contribute to prolapse.Citation20, Citation22, Citation25, Citation26 Over half the women self-reporting prolapse had to carry heavy loads every day, almost all on their backs or heads, which would tighten the abdominal musculature, thereby increasing pressure on the pelvic organs. 74.4% of the women self-reporting prolapse attributed its onset to an event associated with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, of whom 20.0% specifically identified heavy lifting during the post-partum period as the reason for the prolapse, and 27.4% specifically identified lifting heavy loads without mentioning a specific timeframe. Additional reasons for intra-abdominal pressure were excessive workload, sneezing during the post-partum period, chronic cough, while coughing, while pounding rice, while defecating, while climbing trees, heavy lifting during pregnancy and heavy lifting during menstruation. Similar to findings of an earlier hospital-based study in Nepal, which found post-partum onset of prolapse in 55% of participants,Citation22 about one-third of the clinic-based study population cited onset within the immediate post-partum period. 4.5% mentioned lack of trained assistance during delivery as the reason for their prolapse and 0.4% believed it was having “too many babies”.

Respondents, both women and men, in the ethnographic study said how familiar prolapse is in the rural hills, and described the negative consequences for the lives of those affected, most commonly also pointing to the carrying of heavy loads as the cause.

“Women who lift heavy loads immediately after their delivery have this problem, they are more affected. Like those who fetch water in big buckets, or carry loads of wood or do the dhiki (foot milling).” (FGD, women)

“I know why women get it. Listen! After delivery, the uterus is weak. If she doesn't rest and works hard, there is pressure in her stomach and the uterus pushes down and out.” (Female health care worker)

“After delivery, women have to do a lot of heavy work. Like farming and carrying heavy loads. Two years ago we didn't have any running water, so they had to fetch the water too. That is why it happens to them.” (FGD, men)

Women reported that they had no time to rest, often rising between four and five o'clock in the morning and not lying down again until nine in the evening. This schedule did not change with pregnancy.

“Women must get rest, but due to the circumstances, it isn't available. Four or five days ago, a woman went into the jungle alone, but came back with a baby.” (FGD, men)

“I only rested for nine days. On the tenth day, I came home from the goth and started doing all my regular work.” (Woman with prolapse)

“Before delivery, we have no time to rest. We only have time to give birth.” (FGD, women)

“We rest for two or three days after delivery. Then we do the household work. After 11 days, we start fieldwork again.” (FGD, women)

“If a woman lives in a nuclear family, she can't take rest. Even during the first ten days after her delivery she cannot rest. She has to do the light household chores.” (FGD, women)

Experience of onset of genital prolapse

Many of the women with prolapse could recall the exact moment they first felt the prolapse. The individual interviews with women with prolapse revealed a specific event or action that precipitated it:

“I got it 17 days after my first delivery. It was winter and I was sitting by the fire in the squatting position. I sneezed and it came out right then.” (Woman, interview)

“Fifteen days after my delivery, I took the oxen out to graze. One ox ran away. I had to catch it, so I ran after it. After I had taken a few fast steps, it fell.” (Woman, interview)

“On the 12th day after the delivery of my sixth child, I was weeding the field [all day]. When I came home, I squatted by the fire and [at that moment] it came out on its own.” (Woman, interview)

“After my first child it came out. After 13 or 14 days, I was cooking about seven kilos of rice. The pot was very heavy. When I was finished cooking, I asked my sister-in-law to pick up the pot and put it on the ground. But she didn't listen, so I did it myself. It came out right then.” (Woman, interview)

All participants mentioned the same daily activities for women: cooking, cleaning, laundry, animal husbandry, gathering and carrying firewood and grass, gathering and carrying fodder and clay, painting the house, seeding, harvesting, milling grains and childcare.

“All the work except ploughing is done by women.” (FGD, men)

“We don't have time to rest. For us, rest is when we comb our hair!” (FGD, women)

“After we die, we will get some rest.” (FGD, women)

Adverse effects on quality of life, reproductive health and the ability to work

In the clinic-based study, women were asked about the subjective experience of prolapse and its effects on their lives. The type and range of complaints they described seriously jeopardised quality of life, affecting the ability to lift, sit, stand and walk, causing reproductive and urinary tract infections, abdominal and back pain, and making intercourse painful.Footnote*

Table 1 Complaints of women with prolapse (n=518)

All participants in the ethnographic study said that prolapse greatly impaired a woman's ability to work, and this was considered a big problem. There is a direct link between the value of women and their ability to work. Being incapable of working directly threatens their place in the family structure, is humiliating, and often causes women to withdraw from social situations and not talk to others. They may be insulted by the community and their mothers-in-law for not working or staying at home.

“Women must work. Even though they work day and night, there is still not enough food. If they cannot work, how can they get enough food? In this case it is better to die than to live.” (FGD, men)

“Women with prolapse can't work, so how can they raise their children? How can they buy clothes for their children? How can they pay the school fees?” (FDG, women)

“I don't get treatment because I am old and no benefit is expected from me, even after treatment. There is no way around this.” (Elderly woman with prolapse)

Consequences for marital and sexual relations

In a culture where verbal and physical abuse by husbands and mothers-in-law is common,Footnote* the ethnographic study revealed that marital and sexual relations may also be disrupted because of genital prolapse.

“… the husband may marry again because these women can only do simple work and they cannot do the heavy labour.” (FGD, man)

“If [the uterus] goes back inside, the husband will never know about it. If it doesn't go inside, sometimes the husband will take a second wife.” (FGD, women)

“There are two types of prolapse. One is called boke (male goat) and it is the long type. The other is called baaThe (female goat) and it is the round kind. If it is the boke type, intercourse is difficult and in that case the husband may take another wife. But if it is the baaThe type, there is no effect.” (FGD, women)

“If a husband can't have sex because of the prolapse, he will go outside of the marriage for sex … Women have affairs too, but not women with prolapse.” (FGD, men)

“Some husbands insult their wives because of the prolapse. They say, ‘I'll bring another wife.’” (FGD, women)

Discussion

While conclusions on population-wide prevalence cannot be drawn from these data, the sizeable numbers are indicative of the seriousness of the problem of prolapse in western Nepal. The congruency between self-report and a positive diagnosis of prolapse is also noteworthy.

Prolapse not only occurred in multiparous women with inadequate spacing between births who were in their post-menopausal years, but also in young women with no or only one birth, who worked carrying heavy loads. More than half (58.1%) of the women in the clinic-based study and 13 of the 24 women in the ethnographic study had completed two pregnancies or fewer when the prolapse occurred. Perceived causes strongly suggest that multiparity and post-menopause may not be primary causes of prolapse in Nepal, but rather that an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, especially during the immediate post-partum period, is a contributing cause of and risk for genital prolapse.

The findings also provide a glimpse into the quality of life of women with prolapse. In the ethnographic study, it emerged that women's value within family and society was directly related to their ability to bear children and to work. Difficulty handling basic activities jeopardised the women's ability to support their families and had a great impact on their social, physical, familial and emotional lives. The breadth and frequency of complaints show that prolapse has an overarching negative effect on women's lives.

Conclusions and recommendations

After the completion of the clinics in Doti and Achham, the data were analysed, compiled into a report and disseminated in Kathmandu to an audience which included members of the Ministry of Health, relevant line ministries, donor organisations, local and international non-governmental organisations, the Nepal Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and other social and medical organisations. Many projects stemmed from this clinical intervention: a training module on assessment and management of prolapse was designed and integrated into the national training curriculum for district level health workers; a flip chart for counselling was developed and distributed to Female Health Care Workers; follow-up clinics and trainings were held in Doti and Achham districts; Bardiya district held a training and clinic to follow suit from the other two districts; and, finally, grants were obtained to fund corrective surgery–either pelvic floor repair or hysterectomy–for women seen at the clinics.

In addition, the following recommendations were made to the Family Health Division, Ministry of Health, regarding future interventions:

| • | Establish regular gynaecological training and services in rural areas Developing systematic, rotational gynaecological clinics in rural districts is strongly recommended. Such clinics could play a critical role in detecting and managing genital prolapse and other reproductive morbidity in remote areas of Nepal, thereby providing services which would otherwise be unavailable. Rotational gynaecological clinics could also be an excellent medium to bring qualified female physicians into remote areas on a temporary basis. During the clinics, physicians act as role models and teachers for the under-supported and under-supervised district-level health workers. As such, a critical link in maintaining quality of care is fulfilled. We found an impressive willingness within the pool of gynaecologists to see their own country and to serve traditionally neglected populations. We also found district-level staff to be very motivated and supportive of the clinic-and-training model. Training can focus on management of early-stage prolapse because the clinics would provide ample practice for district-level staff to learn how to fit patients for ring pessaries. Patients with ulcerated uterus could receive intermediate care (packing) to heal the ulcers. | ||||

| • | Introduce a genital prolapse check-list. The findings suggest that self-reported prolapse correlates highly with clinically diagnosed prolapse. Therefore, a short checklist should be developed and added to existing checklists used by district-level health workers, particularly for family planning and antenatal patients, to screen for genital prolapse and offer referral. Patients with first- or second-degree prolapse could be seen by previously trained district-level health workers and fitted for ring pessaries. During the next rotational gynaecological clinic, all screened patients could be evaluated for surgery. | ||||

| • | Increase counselling. Counselling for prevention and early management of genital prolapse should be developed and implemented immediately. Such services should be a routine and integral part of all family planning and antenatal clinics as well as the rotational gynaecological clinics. Counselling must include awareness-raising on the risk of prolapse. Men should be encouraged to take over the chores that involve heavy lifting, especially during pregnancy and the post-partum period. Counselling should also encourage families to respect six weeks of post-partum rest for all women. Counselling sessions can use the flip chart which has already been developed for this purpose.Citation27 | ||||

Acknowledgements

We thank the Family Health Division of the Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Nepal, for their support during the entire study. We are grateful to the American Himalayan Foundation, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau and German Federal Ministry, UNFPA and Aktion Familienplanung International for their generous financial contributions. The authors also thank the communities of Achham and Doti for their support, the medical teams and the GTZ project team for organising the clinics.

Notes

* A goth is a small hut or shed which is either attached to the home or which stands separately, and is used to segregate women during their menstruation and the post-partum period. If a family cannot afford a separate hut, women often stay in the same shelter as the animals. Goths tend to have room enough to lay, but not to stand, and have only hay for a bed. A woman staying in a goth is considered polluted and must fetch her own water, cook and clean for herself. She has no access to the warmth of a household fire and is exposed to the elements.

* It is also worth noting the extent of other, possibly related reproductive morbidity diagnosed during the clinic-based studies. Of the 2,072 women with gynaecological complaints who presented at the clinic, 20.1% were diagnosed with a reproductive tract infection, 12.3% with menstrual problems and 17.1% with infertility.

* Of 2,068 women in the clinic-based study who were asked if they had ever experienced abuse, 18.9% reported verbal abuse and 5.2% reported physical abuse, most commonly from husbands, followed by mothers-in-law. The most common reason for abuse was related to the inability to have or care for children, followed by the woman's inability to work (data not shown).

References

- World Health Organization. Report on the Regional Reproductive Health Strategy Workshop: South-East Asia Region. 1995; WHO: Geneva.

- P Christian, KP West, SK Khatry. Night blindness of pregnancy in rural Nepal: nutritional and health risks. International Journal of Epidemiology. 27: 1998; 231–237.

- Nepal Micronutrient Status Survey 1998. 1998; Ministry of Health, Child Health Division, HMG/Nepal, New Era, Micronutrient Initiative, UNICEF Nepal, WHO: Kathmandu, Nepal.

- Ministry of Health Nepal, New Era and ORC Macro. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2001. 2002; Family Health Division, Ministry of Health Nepal; New Era and ORC Macro: Calverton MD, USA.

- A Pradhan, R Aryal, G Regmi. Nepal Family Health Survey 1996. 1997; Ministry of Health Nepal, New Era and Macro International: Kathmandu, Nepal and Calverton MD.

- Bardakova L. Community perceptions of infertility in terms of interpretation, causes, health-seeking behaviour and social consequences in Bardiya District, Nepal. Dissertation, University of Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. (Unpublished)

- L Pathak, D Malla, A Pradhan. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study. 1998; Family Health Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health, His Majesty's Government of Nepal: Kathmandu.

- JB Smith, B Lakhey, S Thapa. Maternal morbidity among women admitted for delivery at a public hospital in Kathmandu. Journal of Nepal Medical Association. 34(118): 1996; 132–140.

- S Thapa, I Basnet. Family planning camps as an opportunity to assess and help reduce the prevalence of reproductive morbidities in rural Nepal. Advances in Contraception. 14: 1998; 179–183.

- LF Banu. Synthetic sling for genital prolapse in young women. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 57: 1997; 57–64.

- KG Fritzinger, DK Newman, E Dinkin. Use of a pessary for the management of pelvic organ prolapse. Lippincott's Primary Care Practice. 1(4): 1997; 431–436.

- DH Nichols, CL Randall. Vaginal Surgery. 4th ed, 1996; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore.

- SL Hendrix, A Clark, I Nygaard. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women's Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 186(6): 2002; 1160–1166.

- GW Davila. Vaginal prolapse: management with non-surgical techniques. Postgraduate Medicine. 99(4): 1996; 171–185.

- N Younis, H Khattab, H Zurayk. A community study of gynaecological and related morbidities in rural Egypt. Studies in Family Planning. 24(3): 1993; 175–185.

- A Bulut, V Filippi, T Marshall. Contraceptive choice and reproductive morbidity in Istanbul. Studies in Family Planning. 28(1): 1997; 35–43.

- J Bhatia, J Cleland, L Bhagaven. Levels and determinants of gynaecological morbidity in a district in South India. Studies in Family Planning. 28(2): 1997; 95–103.

- S Kumar, I Walia, A Singh. Self-reported prolapse in a resettlement colony of north India. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 45(4): 2000; 343–350.

- TKS Ravindran, R Savitri, A Bhavani. Women's experiences of utero-vaginal prolapse: a qualitative study from Tamil Nadu, India. M Berer, TKS Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London, 166–172.

- R Watson. Some observations on “prolapse” in western Nepal. Journal of Nepal Medical Association. 13(3/4): 1975; 88–93.

- Shakya G. Report from a health camp in Jumla, Nepal. 1997. (Unpublished)

- Ranabhat R. Study on risk factors, beliefs and care practices of women with utero-vaginal prolapse, Kathmandu, Nepal. Dissertation, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal, 1997. (Unpublished)

- Bonetti TR. An ethnographic approach to understanding prolapsed uterus in Western Nepal. Dissertation, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, Colorado USA, 2000. (Unpublished)

- UNFPA, Samanata. Focus group study on reproductive health in Nepal from a socio-cultural perspective. Kathmandu, Nepal, 1999. (Unpublished)

- GD Davis. Prolapse after laparoscopic uterosacral transection in nulliparous airborne trainees. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 41(4): 1996; 279–282.

- S Jorgensen, HO Hein, F Gyntelberg. Heavy lifting at work and risk of genital prolapse and herniated lumbar disc in assistant nurses. Occupational Medicine. 44: 1994; 47–49.

- His Majesty's Government of Nepal, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division, GTZ, UNFPA. Reproductive health. Prevention and management of problems related to prolapsed uterus. Kathmandu, Nepal. 2001