Abstract

Since 1970 political and economic changes have brought about great improvements in health and education in Oman, and since 1994 the government has provided free contraceptives to all married couples in primary health care centres. Despite rapid socio-economic development, the fertility rate was 4.2 in 2001. The aim of this study was to define baseline data on ever-married women's empowerment in Oman from a national study in 2000, analyse the correlates of women's empowerment and the effect of empowerment on unmet need for contraception. Two indicators of empowerment were used: women's involvement in decision-making and freedom of movement. Bivariate analysis was used to link these measures and their proxies, education and employment status, with use of a family planning method. Education was a key indicator of women's status. Unmet contraceptive need for women exposed to pregnancy was nearly 25%, but decreased significantly with educational level and paid employment. While empowered women were more likely to use contraception, women's education was a better predictor of “met need” than autonomy, as traditional factors and community influence remain strong. For nearly half the 1,830 women in the study, the husband decided whether contraception was used. Fewer than 1% were using contraception before their first child as women are expected to have a child within the first year of marriage.

Résumé

Depuis 1970, des changements politiques et économiques ont nettement amélioré la santé et l'éducation à Oman, et depuis 1994 les centres de soins de santé primaires fournissent gratuitement des contraceptifs à tous les couples mariés. Malgré un développement socio-économique rapide, le taux de fécondité était de 4,2 en 2001. Cette étude cherchait à définir des données de référence sur l'autonomisation des femmes mariées à Oman à partir d'une étude nationale de 2000, pour examiner les corrélats de l'autonomisation des femmes, et pour analyser l'effet de l'autonomisation sur le besoin insatisfait de contraception. On a utilisé deux indicateurs de l'autonomisation : la participation des femmes à la prise de décision et leur liberté de mouvement. Une analyse bivariée a lié ces mesures et leurs mesures supplétives, l'éducation et le statut de l'emploi, avec l'emploi d'une méthode de planification familiale. L'éducation était un indicateur clé de la condition des femmes. Le besoin insatisfait de contraceptifs pour les femmes exposées à une grossesse était d'environ 25%, mais diminuait sensiblement avec le niveau d'instruction et l'emploi rémunéré. Alors que les femmes autonomes avaient plus de probabilités d'utiliser une contraception, l'éducation des femmes était un moyen plus sûr de prédire un « besoin satisfait » que l'autonomie, puisque les facteurs traditionnels et l'influence communautaire demeurent forts. Pour près de la moitié des 1830 femmes de l'étude, le mari décidait d'utiliser la contraception, et moins de 1% utilisaient une contraception avant la première naissance, puisqu'on attend des femmes qu'elles aient un enfant dans la première année de mariage.

Resumen

Desde 1970, los cambios polı́ticos y económicos en Omán han producido mejoras notables en la salud y la educación, y desde 1994, el gobierno ha suministrado anticonceptivos gratis a parejas casadas en centros de salud primaria. A pesar del rápido desarrollo socioeconómico, la tasa de fecundidad fue 4.2 en 2001. El objetivo de este estudio fue definir datos de lı́nea de base sobre el empoderamiento de mujeres alguna vez casadas en Omán de un estudio nacional en 2000, estudiar los correlatos del empoderamiento de la mujer, y analizar el efecto del empoderamiento sobre la necesidad no satisfecha de la anticoncepción. Se usaron dos indicadores de empoderamiento: la participación de la mujer en la toma de decisiones y la libertad de movimiento. Se aplicó un análisis bivaria para vincular estos indicadores y sus sustitutos—la escolaridad y el nivel de empleo—con el uso de un método de planificación familiar. La escolaridad fue un indicador clave de la condición de la mujer. La necesidad no satisfecha de la anticoncepción en mujeres expuestas al embarazo fue casi un 25%, pero bajó significativamente con el nivel de escolaridad y el empleo remunerado. Si bien era más probable que las mujeres empoderadas usaran un anticonceptivo, la escolaridad de las mujeres pronosticaba mejor la “necesidad satisfecha” que la autonomı́a, ya que los factores tradicionales y la influencia comunitaria se mantenı́an fuertes. Para casi la mitad de las 1,830 mujeres estudiadas, el esposo decidı́a si usaban o no un método anticonceptivo, y menos del 1% usaron un anticonceptivo antes de tener su primero hijo ya que se espera que las mujeres tengan un hijo durante el primer año de matrimonio.

The 1994 International Conference on Population and Development found that the single most important component a nation can invest in to improve its health is the education of girls and women.Citation1 The conference reflected the now commonly understood linkages between education, women's empowerment and demographic indicators.

Since the ascension of His Majesty, Sultan Qaboos bin Said in Oman in 1970, political and economic changes have brought about great improvements in health and education.Citation2 In 2002, infant mortality was 16.2 per 1000 live births compared to 103 in 1975 and life expectancy rates for the same years were 73.8 years compared to 52.7.Citation3 A universal education policy for both boys and girls was introduced in 1970. Thirty years later, Oman is beginning to see the benefits of this policy in a higher percentage of educated women in Oman. Among women aged 60 and over, less than 1% had 12 or more years of education compared to men (4.4%) but for women aged 20–29, nearly half (47%) had completed secondary school (12 years of education) as had 46.5% of men in the same age cohort.Citation4

Despite rapid socio-economic development, 15% of adolescent girls aged 15–20 are married.Citation4 The fertility rate, 4.2 in 2001, remains highCitation3 and large families are common. Compared to a total fertility rate of 7.84 in 1990,Citation5 4.2 represents a dramatic drop. Although similar to other countries of the region (4.12 in Kuwait, 4.24 in United Arab Emirates and 3.11 in Bahrain) the rate is high compared to Europe and North America. Upward rises in educational levels for younger women in these same Gulf countries in 1995 demonstrate the rapid rise in access to education for girls across the region.Citation6 Citation7 Citation8

Because of the high fertility rate, the Ministry of Health initiated a birth spacing programme in 1994. Prior to 1994, women could obtain modern methods of contraception in only a few private clinics in the capital. Since the programme's inception more than eight years ago, efforts have been made to provide contraceptives free to all married couples in primary health care centres which are readily accessible to a majority of the population.

Education, autonomy and contraceptive use

Education has been shown to be more susceptible to improvement through policy intervention than more deeply rooted cultural conventions regarding family size.Citation9 The inverse relationship between women's educational level and fertility has been universally acknowledged, Citation9 Citation10 Citation12 Citation13 Citation14 Citation15 a trend also seen in the Arab world. Citation16 Citation17 Citation18 Citation20 Citation21 Citation22 Martin's comprehensive review of 26 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) identified this as an important link.Citation9

There is also a common assumption that education leads to autonomy as it helps women to stand up to their husbands and provides them a forum to learn about fertility control and make effective use of the health care system.Citation10

Dyson and Moore defined autonomy as the technical, social and psychological ability to obtain information and to use it as the basis for making decisions about one's private concerns and close relations.Citation11 Jejeebhoy identified five interdependent aspects of women's autonomy which are important in the education–autonomy link: autonomy of knowledge (educated women have a wider world view), decision-making autonomy (education strengthens women's say in decisions that affects their own lives), physical autonomy (educated women have more contact with the outside world), emotional autonomy (educated women shift loyalties from extended kin to the conjugal family) and economic and social autonomy and self-reliance (education increases a woman's self-reliance in economic matters and her ability to rely on herself rather than on her children or husband for social status).Citation12

The Women's Global Network for Reproductive Rights calls for women's right to self-determination, including socio-economic and political rights, so that they can make choices regarding their reproductive health.Citation23 Most of the published data, however, including in the most recent DHS, focus only on certain aspects of women's autonomy, such as decision-making and freedom of movement. This paper will also limit itself to these two indicators

As regards fertility control, Ravindran expanded the concept of “unmet need” to refer to women's ability to achieve their reproductive intentions in good health and the ability of reproductive health services to meet those needs.Citation24 However, this broader definition has not yet been incorporated into many fertility-related surveys. For the purposes of this paper, the definition of “met need” is restricted to “using contraception” and “unmet need” to “wants to use contraception” because of limitations in the available data. Although empowerment and autonomy have different connotations, they are often used interchangeably in the literature and similarly in this paper.

A search of the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) website was done for published articles on secondary analysis of data for countries that used the DHS status of women module questionnaire. Although the women's status module of the DHS has been used in at least seven countries, Egypt, the first country to use it, is the only country in the region for which secondary analysis of DHS data has been published.Citation25 Secondary analysis of this data found that the mean level of both empowerment indices (a decision-making index and a freedom of movement index) for Egyptian women increased steadily and significantly with education. They concluded that the relationship of the empowerment indicators for contraceptive need and use, in combination with education, provided a clearer picture on contraceptive need and use than education alone.Citation16 In a similar study of Egyptian women, it was found that more empowered women had fewer children and that education was the most important factor related to women's autonomy.Citation17 Thus, although Angin and Shorter have questioned the relationship between education, empowerment and the use of family planning,Citation26 greater evidence seems to confirm the relationship.

The Child Health Survey, 1990Citation5 Oman Family Health Survey, 1995Citation27 and National Health Survey, 2000Citation4 measured fertility and contraceptive use in Oman. Ever-use of modern contraceptive methods increased in that decade from 16.3% to 35.3% to 50.3% and current use increased from 8.6% to 23.7% to 31.7%, respectively.

Oman has not had baseline data on women's empowerment nor its relationship to contraceptive use. The National Health Survey, 2000 (NHS 2000) was the first to allow the link between the two to be studied. Our aim in doing this study was to define baseline data on ever-married women's empowerment in Oman, study the correlates of women's empowerment and examine the effect of women's empowerment on the unmet need for modern contraception among currently married Omani women.

Methodology

NHS 2000, a community-based survey undertaken by the Department of Research and Studies in the Omani Ministry of Health, had two parts. The first covered lifestyle risk factors and the second reproductive health. The survey sample was selected to be representative of the nation as a whole, using a multi-stage, stratified probability-sampling design. All subjects aged 20 years and above in the selected households were invited to participate. The total number of households selected was 1,968 with a total of 7,011 subjects fulfilling the selection criteria. The reproductive health section included several modules, with questionsFootnote* covering women's background, reproductive health, maternal health, family planning, HIV/AIDS and women's status. Of the 2,037 ever-married women aged 15–49 who responded to the survey, 1,830 were currently married and had heard about family planning methods, answered the questions related to contraceptive use and all the other modules.Footnote*

Two indicators of empowerment were developed from the women's status module to measure women's involvement in decision-making and freedom of movement. To understand the decision-making process, married women were asked “Who has the final say on…” eight decisions: what foods to cook, household expenditure, children's clothes, children's medicine and health care, problem solving, family planning, having another baby and visiting relatives. To measure decision-making power, an index was created (0 to 8) where 0=no responsibility for any of the eight decisions and 1–8=responsibility for 1–8 decisions. Similarly, married women were asked “Does your husband allow you to go alone or accompanied by your childrenFootnote** to…” six places: shopping, hospital/health centre, children's schools, visit relatives, visit friends and go for a walk. Again, an index was used with a range from 0 to 6 (0 = no freedom and 1–6 = 1–6 places women can go). Cronbach-α coefficient was used to measure the reliability of both indices, and showed satisfactory results. Since these two indices did not provide a clear differentiation between autonomy and met and unmet need for contraception, the two indices were computed together to get the women's empowerment scale, ranging from 0 (very low empowerment) to 14 (very empowered).

As regards met and unmet need for contraception, women who were pregnant, infecund or post-menopausal were defined as “not exposed to pregnancy”,Footnote† while women with potential contraceptive need were those who did not want a child within the next two years who were “exposed to pregnancy”. Women exposed to pregnancy were either currently using a modern contraceptive method (met need) or not (unmet need). The reproductive health section of NHS 2000 focused on obtaining information related to the birth spacing programme with questions focusing on modern family planning methods.

Bivariate analysis was used to link the direct measures of women's empowerment, decision-making and freedom of movement indices, and their proxies, education and employment status, with women's use of family planning methods. Due to the multi-dimensional nature of the variables examined, multivariate analysis was used to control for variables that are known to affect both empowerment and contraceptive use, in order to identify and highlight their relationship, namely age, number of living children and place of residence. Multivariate analysis was conducted for the effect of the empowerment index and women's education and employment on both potential contraceptive need status and use status. Several logistic regressions were run to investigate the effects of the different empowerment variables.

Results

Empowerment indicators

Education is one of the key indicators in determining women's status in Oman. There was a clear difference when data on education were disaggregated by age: 38.7% of women aged 25–29 had had secondary education or above compared to only 1.5% of those aged 45–49. Again, in the cohort aged 25–29, a much higher percentage had paid employment (30.3%) than in the cohort aged 45–49, where only 5.3% had paid employment. The difference between these two cohorts in educational level and paid employment is statistically significant (p<0.05, data not shown).

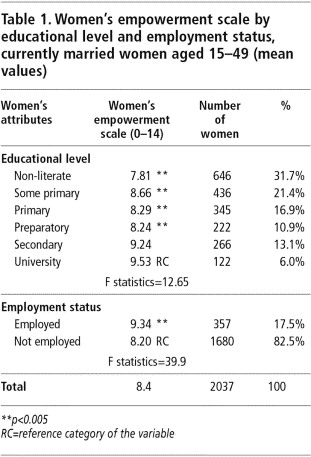

The mean women's empowerment scale for ever-married women was 8.4 . There was a significant difference between different educational levels and the reference category (those with university grades). Similarly, those in paid employment had a higher mean on the empowerment scale.

Indicators and family planning use

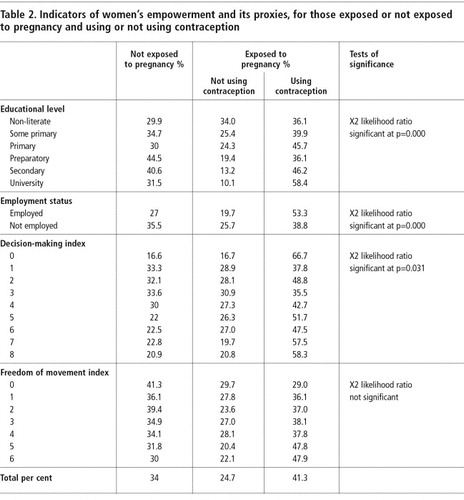

In-depth analysis of these empowerment indicators with women's unmet family planning status in relation to contraceptive use was then carried out (see ). Unmet need was quite high for women exposed to pregnancy, nearly one in four women, but decreased significantly with educational level from 34% for non-literate women to only 10% for those with university education. More than half the women in paid employment were using contraception, another significant relationship.

Nearly 29% of the women who were responsible for only one decision had an unmet need for contraception compared to about 21% of those who were responsible for all eight decisions. Nearly 58% of the women responsible for all eight decisions were using contraception compared to 37.8% involved with only one decision (p<0.05), although the relationship is not as strong as with education.

Of the women who were not allowed to go out alone, almost 30% were not using contraception while a similar percentage were using it. In contrast, only 22% of women who were allowed to go to all six places alone were not using contraception while nearly 48% were using it. Thus, although the more empowered women were more likely to use contraception, it was not a clear-cut linear relationship.

Regression analysis on need and use of contraception

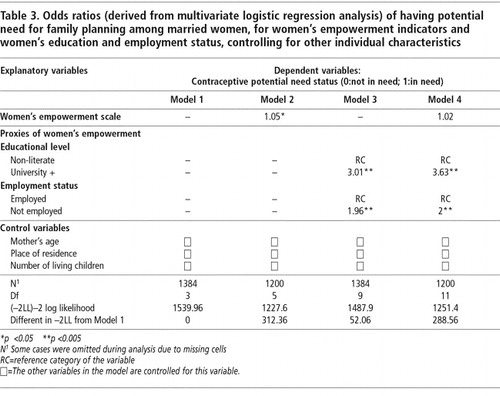

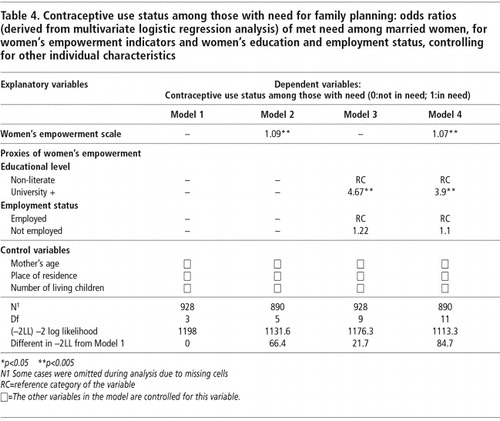

The age of the woman and her number of children significantly predicted use of contraception ; thus, both have been controlled for in the models. Educational level and employment status clearly show their influence in distinguishing those who were exposed to pregnancy from those who were not. The empowerment scale alone predicted those who were exposed to pregnancy compared to those who were not. However, the significance of education and employment status was much stronger than the empowerment scale. In other words, the empowerment scale was no longer significant in predicting who was exposed to pregnancy when combined with education and employment status.

In , a similar analysis was done to determine the effects of the empowerment scale and its proxies, education and employment status, on the probability of a woman's contraceptive needs being met. Women's education had the strongest effect on their use of contraception. Empowered women were more likely to use contraception even after controlling for education and employment status, but women's education seemed to be a much better predictor of “met need” than the autonomy index.

Discussion

The results clearly demonstrate the influence of education on the need for and use of family planning and are likely to be the result of influences such as socio-economic development and government policy of universal education. This confirms previous findings. Citation9 Citation10 Citation11 Citation12 Citation13 Citation14 Citation15 Citation16 Citation17 Citation18 Citation19 Citation20 Citation21 Citation22

A paper by Kishor et al using results from the women's empowerment module of the Egyptian DHS 1995,Citation16 an earlier paper using data from the Egyptian DHS 1989 and national surveysCitation17 are among the few studies on this issue that are readily available from the region. Kishor et al found that mean decision-making of Egyptian women in 1995 on a seven-point scale was 4.7. They were asked “Who has the final say in your family on…”: what foods to cook, the use of contraception, having another child, children's medicine, children's education, budget and visits to friends and family. Around 3% of Egyptian women were not responsible for any of these decisions but nearly 21% were involved in all seven. Regarding freedom of movement, the women were asked “Are you usually allowed to go to…on your own, only with children, only with another adult, or not at all?” The five places included just outside the home, local market, homes of friends and family, local health centre and recreation. The number of places women were allowed to go alone ranged from 3.6% for women not allowed to go to any of the places alone to as high as 35% able to go all five places. The study concluded that Egyptian women's participation in decision-making had the most influence on the need for contraception while freedom of movement was significantly associated with met need for contraception; adding education and employment enhanced the significance of the association.Citation16

Another article by Kishor focused on women's decision-making within the family and employment in the work force. The three autonomy indices she used were: customary (making decisions related to procreation and childrearing), non-customary (making decisions outside these traditional areas) and realised (actual autonomy such as having freedom of movement). The mean level of autonomy in this study was 1.8 out of 5 and education was the most important factor related to women's autonomy. The conclusion was that variables related to modernisation, such as education and socio-economic status, affect women's autonomy. Most interesting was that changes in non-customary autonomy affected the other indices of autonomy and were most closely related to the use of contraception compared to the other indices.Citation22

These and other studies point to the relationship between women's autonomy and contraceptive use,Citation11, Citation12, Citation18, Citation21 and we would have expected that relationship to exist in Oman as well. What is interesting, however, is the relatively weak relationship between women's autonomy, as measured by their decision-making influence in the household and their freedom of movement, and family planning use, and that education has a much stronger influence.

Oman has a well-established health care system with nearly universal access (97%) to primary health care.Citation3 Unmet need for contraception has declined remarkably since the start of the birth spacing programme. Even with the low level of women's autonomy, the wide accessibility of family planning services in all primary health care centres and the ability of the majority of women to visit a health centre on their own (76.0%)Citation4 provide some explanation of the education–contraceptive use link, similar to that in Bangladesh.Citation9, Citation13

Oman is new to the development and modernisation process. In contrast, Egypt became a modern state much earlier, including the establishment of schools for girls before the turn of the 20th century. Oman has only had one generation of adults who have been educated, particularly those under the age of 30. Since cultural and attitudinal changes take time, there could be a generational lag in attitudes towards contraception and fertility. Like other countries in the Gulf, Oman has a mean desired fertility of 5.5 (ranging from 6.2 for non-literate women to 4.7 for university-educated women or higher).Citation4 Similarly, mean desired fertility is 4.7 in Bahrain,Citation6 5.3 in Kuwait,Citation7 and 5.7 in the United Arab Emirates.Citation8 The wealth from the oil industry has led to rapid modernisation in these Gulf states, but there has not been a dramatic concomitant change in cultural views on desired family size.

Although educated women are more likely to need and use family planning, this is not directly linked to autonomy since, for 43.6% of the women in the current study, it is the husband who decides they should use family planning (from 38.5% of non-literate women to 50.4% of university-educated women). Oman is a very gender stratified society, which places limits on the decisions educated women can make (data not shown). As Jejeebhoy has noted, it takes women in highly gender-stratified societies “considerably more education before [they can] overcome these cultural constraints and are involved in decisions seen as major to the household”.Citation12 In short, education and employment do not necessarily enhance autonomy if traditional factors remain strong. Jejeebhoy and Sathar noted that traditional forms of authority (such as age) can have a strong effect on women's autonomy in communities with wide gender disparities.Citation28

An ethnographic study in a working class community in Istanbul, Turkey, questioned the whole idea that education leads to women being empowered and wanting fewer births.Citation26 Although a study in Pakistan found four ways that education affects fertility (it leads to later marriage, to women marrying men with higher income, to women entering the formal employment sector and to unspecified changes in women's values and interests), it found that domestic autonomy failed to predict fertility.Citation14

In Kuwait, the government provides free education through secondary school (and beyond for those who qualify), free health care, housing subsidies and a monthly allowance for each child. Domestic workers are brought in from abroad, which reduces the stress associated with raising a large family. Finally, childbearing remains an essential social role for women.Citation29 Oman is very similar apart from the child allowance. Like Kuwait, Oman is a tribal society in which members of the same tribe are expected to help one another in many different ways, and a family-oriented society in which extended families support each other in raising children.

In highly stratified settings, autonomy may be shaped by traditional factors such as co-residence with mothers-in-law and dowry, as found in a comparative study of India and Pakistan.Citation28 In other communities, however, education and economic development raise most indicators of women's autonomy. In other words, autonomy indices need to be more culture-specific.

The effect of culture on women's autonomy is often attributed to community-level influences. Citation15 Citation28 Citation30 Citation32 Morsund et al found weak links between individual autonomy and fertility indicators when analysing National Family Health Survey data in India. On the other hand, they suggested that literacy among women in a community can generally influence an individual woman's reproductive behaviour beyond that of her own education.Citation30 Morgan et al, in comparing Muslim and non-Muslim communities in four Asian countries, found no relationship between individual autonomy and fertility. One possible explanation was political disadvantage, leading Muslim communities to have higher fertility.Citation31

It would be interesting to create an index incorporating more dimensions of women's autonomy, as Nawar did. Her five-point index covered self-choice of spouse, current participation in the workforce, employment as important to women's personal fulfilment, looking after one's own health, and insisting on one's own opinion or trying to convince or reconcile in case of disagreement. The mean autonomy level on this scale was 1.2 out of 5 with little variation except in relation to women's education (0.9 for non-literate women and 2.3 out of 5 for those with a secondary school or higher education). She also found that more autonomous women were more able to control their fertility and ended up with fewer children at the end of their reproductive years.Citation17

Although the cultural lag in Oman may partially explain the weak link between women's autonomy and fertility indicators, a more comprehensive and culturally-specific index might demonstrate a clearer link between education, autonomy and fertility measures. Several of the items on Nawar's five-point index could be used to measure modernising influences on women's autonomy in Oman, such as self-choice of spouse and participation in the workforce. The wording of the questions on the index items is also key. For example, asking “Does your husband allow you….” demonstrates very limited autonomy and if kept, could be re-worded. Markers of autonomy introduced by Jejeebhoy,Citation12 such as knowledge and physical autonomy, could also be incorporated, and further analysis could be done to measure community influences on autonomy and fertility.

Finally, future demographic and health surveys should obtain information to measure whether women are able to achieve their reproductive intentions in good health,Citation24 as suggested by Ravindran. This would provide a valuable measure of women's autonomy in Oman, as well as measure the success of the birth spacing programme.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Health, UNICEF and UNFPA for their financial support to conduct the National Health Survey. They would also like to thank His Excellency the Minister of Health, their Excellencies the Undersecretaries of Planning, Health Affairs and Financial Affairs, Director Generals at the Ministry of Health, HQ as well as in the regions and a large number of other people within the Ministry of Health for their support.

Notes

* The study questionnaire can be requested from the corresponding author.

* Asking fertility related questions to unmarried women is considered culturally inappropriate; thus, unmarried women were not asked fertility-related questions.

** Women often do not have someone to look after their children when they go out.

† Women who were pregnant were not asked whether or not they wanted to be.

References

- United Nations Population Fund. International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action 1994. 1994; UN: New York.

- AG Hill, LC Chen. Oman's Leap to Good Health. 1996; UNICEF/WHO: Muscat, Oman.

- Oman Ministry of Health. Annual Statistical Report 2001. 2002; Ministry of Health: Muscat, Oman.

- Oman Ministry of Health. National Health Survey 2000. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health.

- Oman Ministry of Health. Child Health Survey 1990. Muscat, Oman: Ministry of Health.

- Bahrain National Health Survey. Riyadh: Gulf Cooperation Council of Health Ministers, 1995.

- Kuwait National Health Survey 1995. Riyadh: Gulf Cooperation Council of Health Ministers, 1995.

- United Arab Emirates National Health Survey 1995. Riyadh: Gulf Cooperation Council of Health Ministers, 1995.

- TC Martin. Women's education and fertility: results from 26 Demographic and Health Surveys. Studies in Family Planning. 26(4): 1995; 187–202.

- KO Mason. The status of women: conceptual and methodological issues in demographic studies. Sociological Forum. 1(2): 1986; 284–300.

- T Dyson, M Moore. On kinship structure, female autonomy, and demographic behaviour in India. Population and Development Review. 9(1): 1983; 35–60.

- SJ Jejeebhoy. Women's Education, Autonomy and Reproductive Behaviour: Experience from Developing Countries. 1995; Clarendon Press: Oxford.

- HTA Khan, R Raeside. Factors affecting the most recent fertility rates in urban–rural Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine. 44(3): 1997; 279–289.

- ZA Sathar, KO Mason. How female education affects reproductive behaviour in urban Pakistan. Asian and Pacific Population Forum. 6(4): 1993; 93–103.

- KO Mason. Gender and family systems in the fertility transition Global Fertility Transition RA Bulatao JB Casterline. Population and Development Review. 27 (Suppl.): 2001; 165–176.

- Kishor S, Ayad M, Way A. Women's empowerment and demographic outcomes: examining links using Demographic and Health Survey data. Paper presented at: Arab Conference on Maternal and Child Health, Cairo, 7–10 June 1999.

- Nawar L. Women's autonomy and gender roles in Egyptian families: implications for family planning and reproductive health. Research Monograph Series No. 25. Cairo: Cairo Demographic Centre, 1996.

- P Govindasamy, A Malhotra. Women's position and family planning in Egypt. Studies in Family Planning. 27(6): 1996; 328–340.

- MA Beydoun. Marital fertility in Lebanon: a study based on the population and housing survey. Social Science and Medicine. 53: 2001; 759–771.

- Chekir H, Farah AA. Household structure and gender perspectives of reproductive behavior of Arab women: evidence from Egypt and Tunisia. Paper presented at: Arab Conference on Maternal and Child Health, Cairo, 7–10 June 1999.

- F El-Zanaty, EM Hussein, GA Shawky. Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 1995. September. 1996; National Population Council Egypt/Macro International: Cairo.

- Kishor S, Autonomy and Egyptian women: findings from the 1988 Egypt Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton, MD: Macro International, Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), (Occasional Papers 2), 1995.

- Women's Global Network for Reproductive Rights. At: 〈www.wgnrr.org〉. Accessed 15 December 2003.

- TKS Ravindran, US Misha. Unmet need for reproductive health in India. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(18): 2001; 105–113.

- Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). At: 〈www.measuredhs.com〉. Accessed 16 September 2002.

- Z Angin, F Shorter. Negotiating reproduction and gender during the fertility decline in Turkey. Social Science and Medicine. 47(5): 1998; 555–564.

- AJM Sulaiman, A Al-Riyami, S Farid. Oman Family Health Survey, 1995. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 47(Suppl.1): 2001; 1–33.

- SJ Jejeebhoy, ZA Sathar. Women's autonomy in India and Pakistan: the influence of religion and region. Population and Development Review. 27(4): 2001; 687–712.

- NM Shah, MA Shah, HL Smith. Patterns of desired fertility and contraceptive use in Kuwait. International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(3): 1998; 133–138.

- A Morsund, O Kravdal. Individual and community effects of women's education and autonomy on contraceptive use in India. Population Studies. 57(3): 2003; 285–301.

- SP Morgan, S Stash, HL Smith. Muslim and non-Muslim differences in female autonomy and fertility: evidence from four Asian countries. Population and Development Review. 28(3): 2002; 515–537.

- Underwood C. WHO Consultant Report on Reproductive Health in Oman, 1998. (Unpublished)