Abstract

Sexual torture constitutes any act of sexual violence which qualifies as torture. Public awareness of the widespread use of sexual torture as a weapon of war greatly increased after the war in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Sexual torture has serious mental, physical and sexual health consequences. Attention to date has focused more on the sexual torture of women than of men, partly due to gender stereotypes. This paper describes the circumstances in which sexual torture occurs, its causes and consequences, and the development of international law addressing it. It presents data from a study in 2000 in Croatia, where the number of men who were sexually tortured appears to have been substantial. Based on in-depth interviews with 16 health professionals and data from the medical records of three centres providing care to refugees and victims of torture, the study found evidence of rape and other forced sexual acts, full or partial castration, genital beatings and electroshock. Few men admit being sexually tortured or seek help, and professionals may fail to recognise cases. Few perpetrators have been prosecuted, mainly due to lack of political will. The silence that envelopes sexual torture of men in the aftermath of the war in Croatia stands in strange contrast to the public nature of the crimes themselves.

Résumé

Le terme « torture sexuelle » désigne tout acte sexuel correspondant à la définition de la torture. L'opinion a pris conscience de l'utilisation de la torture sexuelle comme arme de guerre après le conflit en ex-Yougoslavie, au début des années 90. Les tortures sexuelles ont de graves conséquences mentales, physiques et génésiques. Jusqu'à présent, on a davantage parlé des tortures sexuelles sur les femmes que sur les hommes, partiellement en raison de stéréotypes sexuels. Cet article décrit les circonstances de la torture sexuelle, ses causes et conséquences, et le développement du droit international dans ce domaine. Il présente les conclusions d'une étude réalisée en 2000 en Croatie, où beaucoup d'hommes auraient subi des tortures sexuelles. Des entretiens avec 16 professionnels de la santé et les dossiers médicaux de trois centres soignant des réfugiés et des victimes de la torture ont révélé des indices de viols et d'autres agressions sexuelles, de castration totale ou partielle, de chocs électriques et de coups sur les organes génitaux. Rares sont les hommes qui admettent avoir subi des tortures sexuelles ou qui demandent de l'aide, et les professionnels ne décèlent pas toujours les cas. Peu de responsables ont été jugés, principalement par manque de volonté politique. Le silence qui entoure les tortures sexuelles masculines au lendemain de la guerre en Croatie tranche étrangement avec la nature publique des crimes.

Resumen

La tortura sexual constituye cualquier acto de violencia sexual que se califica como tortura. La conciencia pública del uso amplio de la tortura sexual como un arma de guerra creció enormemente después de la guerra en la antigua Yugoslavia a principios de los años 90. La tortura sexual tiene graves consecuencias para la salud mental, fı́sica y sexual. Hasta la fecha, se ha puesto más atención en la tortura sexual de las mujeres que de los hombres, debido en parte a los estereotipos de género. Este artı́culo describe las circunstancias en que ocurre la tortura sexual, sus causas y consecuencias, y el desarrollo de la ley internacional que la aborda. Presenta datos de un estudio del año 2000 en Croacia, donde pareciera que el número de hombres torturados sexualmente sea significativo. Basado en entrevistas en profundidad con 16 profesionales de salud y datos de los archivos médicos de tres centros que atienden a refugiados y vı́ctimas de tortura, se encontró evidencia de violación y otros actos sexuales forzados, castración total o parcial, golpes y electrochoques en los genitales. Pocos hombres admiten haber sido torturados sexualmente o buscan ayuda, y es posible que los profesionales no reconozcan los casos. Se han procesado pocos perpetradores, por falta de voluntad polı́tica. El silencio que cubre la tortura sexual de hombres en la posguerra en Croacia es un contraste extraño ante el carácter público de los crı́menes mismos.

Public awareness of the widespread use of sexual torture as a weapon of war greatly increased after the war in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s. Attention to date has focused much more on the sexual torture of women than of men, however, and although studies suggest that sexual torture of men is not uncommon, data are almost non-existent.

A major factor in the failure to identify male victims of sexual torture has been the slowness of institutions to recognise that male victims exist. Donnelly and Kenyon argue that health care workers have internalised stereotypical gender roles (men as aggressors, women as victims), to the extent that they are unable to recognise male victims of sexual violence who seek help, and may even dismiss them.Citation1 Male rape survivors, equally affected by gender stereotypes, may have difficulty conceptualising and verbalising what happened.Citation2 In homophobic environments, homosexual survivors of rape may be seen as inviting rape by their very nature.Citation3, Citation4 In around 70 countries, same-sex relations are criminalised and the taboo on homosexuality probably discourages all men who experience sexual torture from reporting it.

Sexual torture of men is slowly gaining recognition, however. In the 1980s, pioneering research was done on sexual torture of political prisoners in Greece,Citation5 ChileCitation6, Citation7 and El SalvadorCitation8 by doctors and psychologists who had personal contact with male survivors. An extensive study of 434 male political prisoners in El Salvador found that 76% reported being subjected to at least one form of sexual torture.Citation8 These authors argued that the sexual torture of men was unrelated to the sexual desires of guards or victims, and should be seen only as an abuse of power.

In the 1990s, gay activists and human rights organisations such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch began to document and publicise human rights abuses based on sexual orientation, including the sexual torture of men.Citation9, Citation10 The records of 184 Sri Lankan Tamil men seeking asylum in London and referred to the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture in 1997–98 showed that 21% reported having been sexually abused.Citation2

A study of 55 civilians subjected to sexual torture who received help from the Bosnian Women and Families project showed that 5.5% were male.Citation11 International fact-finding missions and the United Nations Commission of Experts found many incidences of men who had been sexually violated.Citation12 Citation133 Citation14 Citation15 The media, however, barely reported these cases during the war. An investigation of the Croatian and Serbian Press from November 1991 to December 1993 found only six articles in the Croatian press, compared to over 100 about other forms of torture experienced by Croat men and over 60 about the rape of women. The Serbian press did not publish a single text about sexual torture of men.Citation16 Even in the absence of media attention, news of the sexual torture of men in Croatia spread by other means, e.g. after the war the first author of this article was told that health care workers were having difficulty helping male sexual torture survivors, which prompted the study described in this paper.

This paper summarises contemporary understandings of sexual torture of men, the circumstances in which it occurs, its causes and consequences, national and international laws on sexual torture and how perpetrators are being dealt with. It presents data from a study in 2000 of male sexual torture victims in Croatia, based on data from the medical records of three centres providing medical and psychosocial care to refugees and victims of torture, and on in-depth interviews with 12 therapists and four medical doctors from those centres.

What is sexual torture?

The present international definition of sexual torture is the culmination of five decades of evolving international law on sexual violence in the context of states and war. Under the 1984 Convention against Torture, a given act is torture when it: (1) causes severe physical or mental suffering; (2) is committed for the purposes of obtaining information, punishment, intimidation or coercion; and (3) is inflicted or instigated by or with the consent or acquiescence of any person acting in an official capacity.Citation17 In other words, an act of violence qualifies as torture not because it is cruel, but because it is official, systematic, and coercive or discriminatory. When one person strikes another in the street, that constitutes assault. When a police officer strikes a person in custody to force a confession, that constitutes torture. Sexual torture consists of any act of sexual violence, from forced nakedness to rape, which qualifies as torture. Acts of rape and sexual violence were recognised as forms of torture in the Tadic and Celebici judgements by the International Criminal Tribunal on the Former Yugoslavia.Citation18, Citation19

Circumstances of sexual torture

Rape and other forms of sexual torture are a means of terrorising and controlling a population, e.g. to terrorise an ethnic minority. Governments have probably always used it in both war and peacetime. Sexual torture of women in detention during peacetime has been documented in recent years in dozens of countries, including China, Egypt, Spain and France,Citation20, Citation21 and is also common during war.Citation3 In every armed conflict investigated by Amnesty International in 1999 and 2000, sexual torture of women was reported, including rape.Citation21 Rape of male prisoners and sexual torture of homosexual men are also well documented.Citation22

When sexual torture occurs, it often follows arrests and round-ups of the local population, particularly where repressive governments are faced with armed rebellion. Torture might take place in a field, a school, the victim's own house or a torture chamber or prison.Citation23, Citation24 Like other forms of torture, sexual torture usually takes place during the first week of captivity, most often at night and often when guards are drunk.Citation24 Marginalised groups such as the poor, migrants and ethnic minorities are particularly vulnerable to sexual torture.Citation21

Causes of sexual torture

Sexual violence during armed conflict is sometimes random, the result of a breakdown in the social and legal system.Footnote* In many cases, however, it is organised to further political or military aims. These may include displacing populations, eliciting information from witnesses or providing sexual services for troops. In the former Yugoslavia, according to the United Nations Commission of Experts, “rape and sexual assault seemed to be part of an overall pattern, which strongly suggests that systematic rape did exist”.Citation12, Citation13 Strategic sexual torture is usually not used exclusively but along with other methods for breaking political opponents' wills, including beatings and deprivation of food and sleep.Citation11, Citation26

Regardless of the aims, the main reason why sexual torture becomes epidemic in certain conflicts is a sense of impunity–the absence of fear that the crimes will be punished. Survivors may fail to report sexual torture because they are ashamed or fear that testimony will only subject them to more abuse. Failure to report or punish such crimes creates an atmosphere in which torture may become more widespread.Citation3, Citation20, Citation22, Citation24 To counter the danger of impunity, various national and international legal bodies have endeavoured to outlaw sexual torture and to prosecute its perpetrators.

Health consequences of sexual torture

To be punished, sexual torture must be reported, but sexual torture rarely seems to be reported. Survivors may blame themselves for being tortured, may feel afraid of the social and legal consequences of speaking out, or may be silenced by shame and guilt, which can affect both private and socio-political life.Citation8, Citation27 Partners and friends suspecting problems may avoid the topic, contributing to their sense of isolation.Citation28 In these ways, sexual torture may succeed in breaking a person's will.

Those who do report sexual torture usually turn first not to the legal system but to health care providers–a less confrontational, more confidential avenue. Health care personnel encounter cases of sexual torture because survivors present with complaints of physical, psychosomatic or psychosocial ailments.Citation27 The worst cases may have suffered castration. Rape victims may have sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, or unwanted pregnancies; all of these were frequent in Rwanda, for example.Citation29 Men may suffer from genital infections, physical impotence, swollen testicles, blood in their stools, abscesses and ruptures of the rectum.Citation30

Men and women report psychosomatic problems, including headache, loss of appetite and weight, sleeplessness, palpitations, dizziness and exhaustion. Survivors may express deep feelings of shame, guilt, anger, anxiety, emotional desensitisation, suicidal thoughts, nightmares and loss of interest in sex, leading to post-traumatic stress disorder. Men may describe impotence for which no physical cause can be found or premature ejaculation.Citation31

Survivors have experienced psychosocial problems, including marital problems, social withdrawal and loss of interest in work, inexplicable outbursts of anger, and alcohol and drug abuse. Male and female survivors often have intrusive thoughts about the torture during intercourse. Sexual torture victims, like other torture victims, may report trouble trusting others or establishing relationships. Male survivors have felt the need to ask whether the fact of having been raped makes them homosexual or attractive to homosexuals.Citation8, Citation32 One source of confusion for survivors is that they may have had an erection during the rape and mistakenly consider this proof of sexual excitement.Citation2 Van Tienhoven's male clients often mention their fear of no longer being able to function as a man.Citation30

Few of the above-mentioned symptoms provide reliable clues on their own that sexual torture has occurred. Abrasions and other physical evidence usually fade after a few weeks and leave no trace. When there are physical traces, they are not always self-explanatory. Survivors who have contracted STIs may not mention the torture when asked how they might have been infected. As other forms of torture mostly accompany sexual torture, victims may present multiple physical, psychosomatic and psychosocial problems that may not be easy for health care workers to unravel.

National and international law on sexual torture

Before World War II, rape and sexual violence were considered inevitable by-products of war or ascribed to renegade soldiers. Even at the Nuremberg trials, not a single case of rape was punished.Citation23

The 1949 Geneva Conventions on the Protection of Civilians in Time of War were the first in which international law addressed wartime sexual violence. Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions explicitly outlaws “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment, rape, enforced prostitution, and any form of indecent assault”.Citation33 The 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which in Article 1 gives the definition of torture still accepted today,Citation17 does not specifically mention sexual violence as a form of torture, however.

Legal recognition that sexual violence could constitute torture came as a result of the war in the former Yugoslavia, with its abundant testimony by female rape survivors. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was mandated to try the perpetrators of heinous crimes (genocide, crimes against humanity, violations of the laws of war and serious breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions) committed during the conflict.

In its Celebici judgment, the ICTY established that sexual violence constitutes torture when it is intentionally inflicted by an official, or with official instigation, consent or tolerance, for purposes such as intimidation, coercion, punishment, or eliciting information or confessions, or for any reason based on discrimination.Citation19 In the Furundzija case, the court recognised that not all perpetrators need to be officials, requiring only that “at least one of the persons involved in the torture process must be a public official or must at any rate act in a non-private capacity”.Citation34

Under the ICTY Statutes, adopted in 1993, torture may be prosecuted as a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions (Article 2(b)), as a violation of the laws or customs of war (Article 3), or, where particularly systematic, as a crime against humanity (Article 5(f)). Crimes against humanity include rape or other inhumane acts when committed systematically or on a mass scale against civilians.Citation35

Even where sexual violence is not organised, a number of decisions by international and regional bodies have held that rape by security, military or police officials always amounts to torture.Citation36, Citation37

In 1998 the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) broadened the legal definition of sexual violence: “Sexual violence is not limited to physical invasion of the human body and may include acts which do not involve penetration or even physical contact”,Citation38 e.g. forced nakedness.

Some women's and human rights organisations have called for broadening the definition of sexual torture to encompass systematic violence against women by private actors, e.g. female genital mutilation.Citation21 Gay and human rights organisations have sought to have the prohibition of discriminatory punishment in the Convention against Torture applied to countries which criminalise homosexuality.Citation22

Dealing with the perpetrators

Countries that have ratified the 1984 Convention against Torture, such as the former Yugoslavia, are legally obliged to prosecute perpetrators in national courts. However, the perpetrators of torture very often are government officials, such as police or military officers, and governments are usually reluctant to prosecute their own officials.

When national courts fail to prosecute torture, international courts can step in, but such interventions have been rare. The ICTY and the ICTR constitute the most significant efforts to date to prosecute perpetrators of sexual torture and other wartime crimes under international law. Yet by 2003, proceedings at the ICTY, whether for torture or other crimes, had been undertaken or completed on behalf of only about 90 persons. Many thousands of those responsible for atrocities in Bosnia-Herzegovina have yet to be brought before any court.Citation39 The establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in 2003, empowered to prosecute crimes against humanity, genocide and crimes of war was a milestone, but it remains to be seen how effectively this court will prosecute sexual torture.

The main problem in prosecuting the perpetrators of torture has been the lack of political will to implement the law. Citation21 Citation22 Citation23 Still, the decisions of the ICTY have sent a clear message that the days of complete impunity are over.

Sexual torture of men in Croatia

Methodology

A literature search on sexual torture of men was conducted among publicly available documents at the ICTY and in the library of the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims in Denmark. In addition, the gender crime specialist at the ICTY was interviewed and requests for information were sent to more than 55 human rights activists and researchers, mental health specialists and gender specialists internationally and at the on-line United Nations Development Programme conference on women in armed conflicts in 1999. Keywords used during the literature search were gender and sexual violence, sexual torture, torture, male sexual torture, verdicts of sexual torture, war crimes and gender.

In December 1999, in an exploratory research visit to Croatia, three organisations that had treated male survivors of sexual torture were identified: the Medical Centre for Human Rights, a Croatian NGO providing medical and psychosocial care to refugees and internally displaced persons; the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, an international NGO providing medical and psychosocial care specifically for torture victims; and the Centre for Psychotrauma at the University of Rijeka in the State Hospital of the city of Rijeka, which provides psychosocial treatment for war veterans.

Pre-tested questionnaires were sent to these centres, asking them to provide data from the medical records of their patients, including the number of sexual torture cases, their nationality and whether they were soldiers or civilians, and the type of torture they suffered under the headings of rape, forced sexual acts, full or partial castration, genital beatings or electroshock. These classifications were based on descriptions of sexual torture in the literature.

Further document research was conducted in a follow-up visit to Croatia in March 2000. Twelve therapists and four medical doctors at the three centres were interviewed regarding the identification and treatment of male sexual torture survivors. Questions covered symptoms, how the topic of sexual torture was broached and strategies for treatment, outreach to family and community and reintegration into society. Two group therapy sessions were observed using an interpreter.

The three centres provided data on three very different populations. The International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims provided data for 22 civilian male victims of torture enrolled in its group therapy programme.

Teams from the Medical Centre for Human Rights working with displaced persons and refugees in housing locations in Zagreb, Dalmatia, Rijeka, Slavonia and Bill collected 2,500 testimonies from men and women between 1992 and 1994, of whom 1,648 were men. Time constraints prevented them from identifying methods of sexual torture or other data requested. However, since 1995, they have been running an outreach and treatment programme for male survivors of sexual torture, from which they furnished in-depth data on 55 male sexual torture survivors. The data included the status of the alleged perpetrators, the political affiliation of the victims, the number of witnesses, excerpts of testimonies and a report of their findings. They also provided nine unpublished testimonies from male sexual torture survivors.

The Centre for Psychotrauma provided quantitative data for 5,751 war veterans treated at the centre between 1994 and 2000. It also provided data from a smaller number of civilians; the number could not be established because civilians, while sometimes treated, were not officially registered.

Incidence of sexual torture

It was not possible to calculate or even estimate the incidence of sexual torture in wartime Croatia. Only a small proportion of survivors are likely to have admitted to having been sexually tortured. Many victims may have been killed. Their remains, even if discovered, may not show evidence of sexual torture. Thus, the study was not designed to measure incidence. However, it is possible to try to develop a broad sense of whether sexual torture of men occurred often enough to be considered a regular feature of wartime violence or limited to a few exceptions.

Among the 22 male torture survivors in the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture (ICRT) Victims Programme, 14 reported having suffered some type of sexual torture, ten suffered genital beatings or electroshock, and four had been raped.

Of the 1,648 testimonies screened by Medical Centre for Human Rights (MCHR) staff, 78 self-reported sexual torture. Among the 55 survivors of sexual torture who sought help from MCHR, 24 were subjected to genital beatings or electroshock, 11 were raped, seven were forced to engage in sexual acts and 13 were fully or partially castrated. In addition, MCHR staff had found six post-mortem cases of total castration.

Comparatively few self-reported cases of sexual torture were found by the Centre for Psychotrauma. Of the 5,751 Croatian war veteran patients, nine reported having suffered genital beatings and/or electroshock, and five reported rape. Among the unknown number of male civilians, one reported having been raped and three reported genital beatings.

The data from the ICRT and the MCHR support the conclusion that sexual torture of men was a regular, unexceptional component of violence in wartime Croatia, not a rare occurrence. The data from the Centre for Psychotrauma were probably at variance because of the nature of the sample and the attitudes of at least one therapist.

Factors affecting reported rates

Obviously, the groups at the three centres are not comparable in many ways. The war veterans at the Centre for Psychotrauma had not necessarily been prisoners of war. Those who were never detained were unlikely to have been tortured, so it is not surprising that a very low rate of sexual torture was reported. The therapy group of torture victims at the IRCT had all been tortured and had voluntarily joined the therapy group; hence, they were self-selected for willingness to speak about these traumatic experiences. The refugees and displaced persons interviewed by MCHR were a marginalised population who by nature were vulnerable to torture.

However, other factors also seem to have influenced reporting rates. Therapists at the Centre for Psychotrauma found it difficult to discuss the topic of sexual torture of men. One therapist said that she had not believed that men could be raped until one night a man was brought in naked and bleeding from the anus. Such an attitude probably discouraged her from looking for sexual torture of men and may have discouraged men from reporting it.

The MCHR staff, in contrast, engaged in active outreach to find and treat male survivors of sexual torture. Dr Loncar who led the MCHR therapy group for the 55 survivors had himself been an inmate of a detention camp; survivors may have been more willing to discuss their experiences with a fellow detainee.

The all-male therapy group at IRCT also provided an open environment for men to report sexual torture. Many of the men had known each other in the detention camps. According to the therapist, once one of them had spoken about being sexually tortured in the camp, it was difficult for the others to remain silent. The therapist also seemed open to discussing the topic, which may also have played a role. Other therapists, including a male psychiatrist at the same centre, had found only a few cases over a five-year period.

It is possible that the female therapist at IRCT and the survivors of sexual torture gravitated towards each other, so that she did not so much bring more survivors out of the closet as gather more survivors into her group. But her case contributes to the sense that interlocutors who are unaware of or uncomfortable with the possibility of sexual torture of men may fail to discover (many) cases and inadvertently deter survivors from seeking medical or legal remedies.

Psychosexual and psychosocial effects of sexual torture

As reported in other studies, all of the survivors reviewed presented at least one psychosomatic complaint, e.g. headache, muscle ache, vomiting, stomach ache or sweating. All the therapists reported that survivors had concerns about their masculinity. More than half the 55 survivors at MCHR in Zagreb suffered from sexual dysfunction for which no physical cause could be found, including impotence, problems maintaining an erection and pain during sexual intercourse. All those suffering from impotence were convinced that the problem was physical and caused by the torture. In each case, it was not until a urologist was able to show them that they were capable of an erection that the therapists were able to discuss psychological causes.

Therapists also found that all survivors suffered from psychosocial problems including anxiety attacks, fear of their own anger and inability to handle conflict. During the two therapy sessions observed, these problems dominated the discussion. One survivor, for example, decided to seek help from ICRT after he found himself holding a handful of his five-year-old daughter's hair, unable to remember why he was angry. Survivors said they felt isolated and afraid and unable to make contact with others.

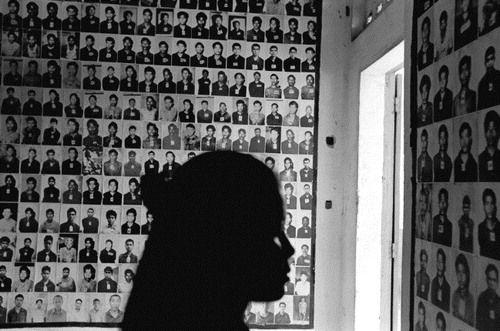

An open secret

One of the striking points to emerge from the study is how silent male survivors of sexual torture have remained about their experiences. In the MCHR therapy group, specifically advertised as a group for male survivors of sexual torture, none of the men who showed up would initially admit to having suffered sexual torture themselves; they claimed they had come on behalf of friends. It was only after some time that group members acknowledged they had been tortured. In the ICRT group, none of the survivors mentioned sexual torture during intake interviews. Other types of torture were discussed relatively openly, but sexual torture was not broached until later in therapy, according to the therapists.

Torture is often carried out in public to demonstrate the power of the perpetrators. Narratives by male survivors show that torture was frequently perpetrated by groups and in full and deliberate view of bystanders. The example below illustrates the public nature of the sexual torture:

“First they grabbed X and pushed him down by the road. He was the weakest… Four men pushed him down and were holding his head, legs and arms. Y approached him, she had a scalpel in her hand. The men who pushed him down took his trousers off. She castrated him. We had to watch. I was watching, but I was so scared that I did not see much… One of the Chetniks had a wooden stick and he hit X a few times across his neck. X showed no signs of life anymore. Then three Chetniks shot at X. The fourth took a pistol and shot him in the head.” (Unpublished testimony, a soldier at MCHR)

The silence that envelopes the sexual torture of men in the aftermath of the war in Croatia stands in strange contrast to the public nature of the crimes themselves.

Discussion

As shown in the literature and confirmed by our study, sexual torture of men in wartime occurs regularly. While there are certain specific differences in the sexual torture of men and women and its effects, the psychological symptoms experienced by male and female survivors seem to be substantially similar.

In fact, perpetrators seem to torture both men and women sexually. Although more women than men have reported sexual torture in some studies, lack of recognition may discourage male survivors from reporting sexual torture even more than women, and professionals may fail to recognise cases. Few men admit being sexually tortured or seek help. Health professionals, the legal system and human rights advocates have proven to be somewhat gender-biased about sexual torture and have only recently begun to acknowledge that men as well as women are potential victims. It is difficult enough for survivors of sexual torture to come forward; men should not have to face the additional problem of disbelief that it could even happen to them at all.

The occurrence of sexual torture of men during wartime and in conflict situations remains something of an open secret, although it happens regularly and often takes place in public. These shortcomings are a critical barrier for those needing treatment and legal assistance, and limit the possibility of action against the perpetrators. The challenge is to turn this open secret into a recognised fact, so that it can be deterred and prosecuted alongside the sexual torture of women.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Doctors without Borders, Netherlands. The authors wish to thank all those in Croatia who made the study possible: the staff of the Medical Centre for Human Rights, in particular Dr. Mladen Loncar; the International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims in Zagreb; the Centre for Psychotrauma at the Medical Faculty, University of Rijeka; and the Centre for Direct Protection of Human Rights. We would also like to thank Wies van Bemmel for bringing this topic to our attention and Frank Stevens, the gender specialist at Amnesty International, Netherlands, for mobilising his network.

Notes

* A detailed description and analysis of the relationship between the breakdown of social norms and values and sexual violence can be found in a recent Human Rights Watch report on the eastern Congo.Citation25

References

- DA Donnelly, S Kenyon. “Honey, we don't do men”. Gender stereotypes and the provision of services to sexually assaulted males. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 11: 1996; 441–448.

- M Peel, A Mahtani, G Hinshelwood. The sexual abuse of men in detention in Sri Lanka. Lancet. 355(9220): 2000; 2069–2070.

- L Shanks, N Ford, M Schull. Responding to rape. Lancet. 357(9252): 2001; 304.

- TK Daugherty, JA Esper. Victim characteristics and attributions of blame in male rape. Traumatology. 4(2): 1998; 342–348.

- G Daugaard, H Petersen, U Abilgaard. Sequelae to genital trauma in torture victims. Archives of Andrology. 10: 1983; 245–248.

- J Cienfuegos, C Monelli. The testimony of political repression as a therapeutic instrument. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 54: 1983; 43–51.

- R Dominguez, E Weinstein. Aiding victims of political repression in Chile: a psychological and psychotherapeutic approach. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psyckologforening. 24: 1987; 75–81.

- I Agger. Sexual torture of political prisoners: an overview. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2: 1989; 305–318.

- Amnesty International UK Gay and Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Network. Breaking the Silence: Human Rights Violations Based on Sexual Orientation. 1997; Amnesty International UK: London.

- Human Rights Watch. All Too Familiar: Sexual Abuse of Women in US State Prisons. 1996; Human Rights Watch Women's Rights Project: New York.

- LT Arcel, GT Šimunkovic. War Violence, Trauma and the Coping Process; Armed Conflict in Europe and Survivor Responses. 1998; Nakladništvo Lumin: Zagreb.

- United Nations Commission of Experts' Final Report. Annex IX- Rape and Sexual Assault. United Nations Security Council. S/1994/674/Add.2 (Vol. V). 1994; United Nations: Geneva. 28 December.

- United Nations Commission of Experts' Final Report. Annex IX-A- Sexual Assault Investigations. United Nations Security Council. S/1994/674/Add.2 (Vol. V). 1994; United Nations: Geneva. 28 December.

- Mazowiecki T. Periodic reports on the human rights situation on the territories of former Yugoslavia, by the UN Commission for Human Rights Special Rapporteur, Mr. Tadeusz Mazowiecki. 1992: E/CN.4/1992/S-1/9, Geneva: United Nations, 1992.

- United Nations Commission of Experts' Final Report. Section IV: Substantive Findings (E. Detention Facilities; F. Rape and Other Forms of Sexual Assault). United Nations Security Council. S/1994/674/Add.2 (Vol.V). Geneva: United Nations, 27 May 1994.

- D Zarkov. The body of the other man: sexual violence and the construction of masculinity, sexuality and ethnicity in the Croatian media. C Moser, F Clark. Victims, Perpetrators or Actors? Gender, Armed Conflict and Political Violence. 2001; Zed Books: London, 69–82.

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, G.A. Res. 39/46, [Annex, 39 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No. 51) at 197, U.N. Doc. A/39/51 (1984)], entered into force June 26, 1987. Geneva: United Nations, 1984.

- Prosecutor v. Dusko Tadic, Case No. IT-94-1I, 10 February 1995.

- Celebici Judgement, Prosecutor v. Delalic, Mucic, Delic, and Landzo, Case No. IT-96-21-T, Para. 770, November 1998.

- Amnesty International, International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development. Documenting Human Rights Violations by State Agents: Sexual Violence. Montreal: ICHRDD, 1999.

- Amnesty International. Broken bodies, shattered minds, torture and ill-treatment of women. Amnesty International Index: ACT 40/001/2001: 2001. 2001; Amnesty International Publications: London.

- Amnesty International. Crimes of hate, conspiracy of silence: torture and ill-treatment based on sexual identity. Amnesty International Index: ACT 40/016/2001. 2001; Amnesty International Publications: London.

- Asian Legal Resource Centre. Specific contexts of sexual torture and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment. Armed conflict, Police/Penal. At: 〈http://www.alrc.net/mainfile.php/torture/151/〉. Accessed 11 November 2002.

- Amnesty International. A Glimpse of Hell: Reports on Torture Worldwide. D Forrest. 1996; New York University Press: New York.

- Human Rights Watch. The War within the War: Sexual Violence against Women and Girls in Eastern Congo. 2002; Human Right Watch: New York. June.

- Bosnia Herzegovina. “A Closed, Dark Place”: Past and Present Human Rights Abuses in Foca: 1998. Human Rights Watch. 10(6): 1998.

- RF Mollica, JP Lavelle. Southeast Asian refugees. L Comaz-Diaz, EEH Griffith. Clinical Guidelines in Cross-Cultural Mental Health. 1985; Wiley and Sons: New York, 262–304.

- SW Turner. Surviving sexual assault and sexual torture. GC Mezey, MB King. Male Victims of Sexual Assault. 1992; Oxford University Press: New York, 75–86.

- P Donovan. Rape and HIV/AIDS in Rwanda. Lancet. 360(Suppl): 2002; S17–S18.

- H Tienhoven. Sexual violence, a method of torture also used against male victims. Nordisk Sexology. 10: 1992; 243–249.

- J Ortman, I Lunde. Prevalence and sequelae of sexual torture. Lancet. 336(8710): 1990; 289–291.

- Lira E. Weinstein E. La tortura sexual: ponencia para el seminario «Consecuencias de la represion en el cono Sur: sus efectos médicos, psicológicos y sociales». Montevideo, Uruguay, 1986.

- Geneva Conventions, Protocol II, Article 4(2)(e). Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts (Protocol II), 8 June 1977. At: 〈http://www.icrc.org/IHLnsf/0/f9cbd575d47ca6c8c12563cd0051e783?OpenDocument〉. Accessed 2 February 2004.

- Prosecutor v. Anto Furundzija, Case No. IT-95-17/1-T, December 1998.

- Statute of the International Tribunal (Adopted 25 May 1993). At: 〈http://www.un.org/icty/basic/statut/statute.htm#2〉. Accessed 16 April 2000.

- Fernando and Raquel Mejia v. Peru, Report No 5/96, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 1 March 1996.

- Report to the UN Commission on Human Rights, 12 January 1995, UN Doc. E/CN.4/1995/34, Para.189, Geneva: United Nations, 1995.

- Prosecutor v. Akayesu, ICTR-96-4-T, Trial Chamber 1, Para. 688, 2 September 1998.

- Amnesty International, Bosnia-Herzegovina Shelving justice–war crimes prosecutions in paralysis, INDEX: EUR 63/018/2003. At: 〈http://web.amnesty.org/library/Index/ENGEUR630182003?open&of=ENG-BIH〉. Accessed 2 February 2004.