Abstract

In Lao PDR, evidence is emerging of considerable sexual activity among unmarried youth, but contraceptive services remain inadequate to meet their needs. This study explored the attitudes of formal and informal sector providers in serving the contraceptive needs of unmarried youth in Vientiane Municipality, their perceptions of quality of care, confidentiality and privacy, level of comfort in discussing sexual matters, and any differences between providers in the two sectors. In-depth interviews were carried out with 56 key informants, followed by a quantitative survey of 150 formal sector and 100 informal sector providers. We found ambivalence and discomfort among providers in communicating with unmarried youth and providing contraceptives to them, and low priority placed on their right to privacy and confidentiality. Providers tended to attribute difficulties almost entirely to young people's inhibitions and unwillingness to listen. Less than 60% of formal sector providers would supply contraceptives to unmarried youth, compared to 80% of informal providers, but the latter were more likely to charge a fee for supplies. Both formal and informal sector providers need training in communication and counselling skills for serving unmarried youth. Programmes must ensure that unmarried youth have access to good quality contraceptive services and supplies.

Résumé

Les recherches commencent à révéler qu'en République démocratique populaire lao, les jeunes célibataires ont une activité sexuelle considérable, mais les services de contraception demeurent insuffisants. Une étude a analysé la réponse de fournisseurs de contraceptifs du secteur formel et informel à la demande d'adolescents dans la Préfecture de Vientiane, leurs perceptions de la qualité des soins, la confidentialité, le niveau d'aisance dans la discussion de la sexualité, et toute différence entre les fournisseurs des deux secteurs. Des entretiens ont été menés avec 56 informateurs clés, suivis d'une enquête quantitative auprès de 150 fournisseurs du secteur formel et 100 du secteur informel. Les fournisseurs étaient ambivalents et mal à l'aise quand ils communiquaient avec les jeunes célibataires et leur procuraient des contraceptifs ; ils accordaient une faible priorité à leur droit à la confidentialité. Les fournisseurs attribuaient presque entièrement ces difficultés aux inhibitions des jeunes et à leur refus d'écouter. Moins de 60% des fournisseurs du secteur formel acceptaient de donner des contraceptifs à des jeunes célibataires, contre 80% dans le secteur informel, mais ces derniers risquaient davantage de faire payer les contraceptifs. Les fournisseurs des deux secteurs avaient besoin d'être formés à la communication et aux conseils. Les programmes doivent veiller à ce que les jeunes célibataires bénéficient de services de qualité et aient accés aux contraceptifs.

Resumen

En la República Popular Democrática de Laos se empieza a constatar una actividad sexual considerable entre jóvenes solteros, cuya necesidad de anticonceptivos permanece insatisfecha debido a la falta de servicios adecuados. Este estudio exploró las actitudes de proveedores de los sectores formales e informales al atender las necesidades anticonceptivas de adolescentes en la Prefectura de Vientiane, sus percepciones de la calidad de atención, confidencialidad y privacidad, grado de comodidad al hablar de temas sexuales, y diferencias entre los proveedores en los dos sectores. Se realizaron entrevistas con 56 informantes claves, seguidas por una encuesta cuantitativa a 150 proveedores del sector formal y 100 del sector informal. Encontramos ambivalencia e incomodidad en los proveedores al comunicarse con los jóvenes solteros y proveerlos con anticonceptivos. Dieron poca prioridad a su derecho a confidencialidad y privacidad. Los proveedores solı́an atribuir las dificultades casi enteramente a las inhibiciones y la inatención de los jóvenes. Menos de un 60% de los proveedores del sector formal proveerı́an anticonceptivos a los jóvenes solteros, comparado con un 80% de los proveedores informales, pero era más probable que estos últimos cobraran algo por los suministros. Los proveedores de ambos sectores necesitan capacitación en comunicación y consejerı́a para atender a jóvenes solteros. Los programas deben garantizar su acceso a servicios y suministros anticonceptivos de buena calidad.

Young people's knowledge, skills and access to sexual and reproductive health services are limited in Lao PDR as they are not yet perceived as a vulnerable group with special needs. Yet there is emerging evidence in the country of considerable sexual activity among unmarried youth.Citation1 A survey by the National Statistics Centre found that about 8% of unmarried youth had engaged in premarital sex and that the use of contraceptives among adolescents was very low and increased only slowly with age. It was 3% among adolescents aged 15–17, 6% among adolescents aged 18–19 and 12% among young people aged 20–25. Adolescent boys were four times more likely to use a contraceptive than girls (8.8% vs. 1.8%). About 8% of young people aged 20–25 had ever used condoms.Citation2

Abortion is illegal in Lao PDR and owing to socio-cultural factors as well as financial constraints, abortion is more likely to be performed under clandestine and unsafe conditions by untrained practitioners. Although there are no accurate prevalence data, evidence of young women treated for complications of abortion points to high rates of unsafe abortion among the younger age groups.Citation3 In a major national study, the incidence of induced abortion appeared to be low in the upland villages because of high infant and child mortality, lack of information about abortion services and difficulties accessing health services generally and abortion in particular. In the lowland villages abortion is more common, but people are reluctant to discuss the issue, especially in relation to young, unmarried women.Citation4

Family planning services in Lao PDR

According to the Lao national policy on provision of contraceptive methods: “Birth spacing methods and services will be provided free to everyone who needs them, irrespective of sex, marital status or residence. The acceptance of birth spacing methods must be uncoerced and on a voluntary basis. All contraceptive methods provided to the population by whatever source should be safe for the health of the users, as the first priority”.Citation5

Family planning services are indeed widely available from both formal and informal sector providers in Lao PDR. The public health sector provides contraceptives through family planning units located in hospitals and through village health volunteers (or community-based distributors) who promote birth spacing and distribute condoms and pills for a nominal charge or free. Family planning units are responsible for counselling services and the distribution of contraceptives. These units are often based in maternal and child health (MCH) centres at central, provincial and district hospitals. Private clinics and providers, especially obstetrician–gynaecologists, also provide contraceptive services. The informal sector includes drugstore sellers, traditional healers and condom distributors at guesthouses.

However, access to these services is quite different for married compared to unmarried youth. Family planning units are not attended by unmarried young women or men, many of whom prefer to obtain contraceptives from private sector providers or pharmacies.Citation6 While public sector services are, in theory, accessible to all irrespective of age or marital status, they tend to be of limited quality and not accessible to single people, according to district health staff in informal discussions with care providers in a district hospital in Vientiane Province in November 2001. Thus, family planning services for unmarried youth in Lao PDR are inadequate.

The difficulties faced by unmarried youth in accessing contraceptive services and in service utilisation may, in part, be related to providers' negative attitudes towards young people, discomfort in discussing sexuality and poor quality of services.Citation5, Citation7 Few studies have explored whether providers themselves recognise or contribute to the existence of these obstacles. We conducted a study to explore the experiences and attitudes of providers in serving the contraceptive needs of unmarried young people in Vientiane Prefecture and Vientiane Province. It examined providers' perceptions of quality of care, confidentiality and privacy for young people, and sought to determine if there were any differences between formal and informal sector providers. It also focused on the extent to which providers offered unmarried youth contraceptive supplies and felt comfortable discussing sexual matters with them.

Methodology and participants

The study was conducted during 2000–2001 in Vientiane Prefecture and Vientiane Province in the central region of the Lao PDR, each of which contains nine districts. The sample of providers was drawn from all 18 districts. Vientiane Municipality was selected not only because 18% of the Lao population live there, but also because youth in these settings are more likely than those in other regions to engage in sexual activity.Citation2 Additionally, there are a variety of providers serving young people's sexual and reproductive health needs in these provinces.

The study consisted of a mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods. In-depth interviews with 56 key informants were carried out initially. The key informants identified the following providers: eight doctors, eight nurses and midwives and eight health volunteers in the formal sector (both public and private), and in the informal sector, seven traditional healers, ten drugstore personnel and employees of seven guesthouses frequented by young people to engage in sexual relationships. These providers were identified by discussion with provinical and district health staff, village headmen and representatives of the Lao Women's and Youth Unions. They were chosen purposively, based on their experience providing contraceptive services to youth. Both formal and informal sectors were interviewed in depth about their experience providing contraceptive services, attitudes towards providing services and perception of communication with young clients. The information gathered from the key informants was used to construct the interview questions.

The interviews were followed by a survey of 250 providers—150 from the formal sector and 100 from the informal sector—who were selected purposively, using a quota sampling method, and were involved in supplying contraceptives and providing counselling and information on contraception at community level. The formal sector providers included 45 doctors, 35 nurses/midwives, 30 private clinic doctors and 40 village health volunteers. Informal sector providers included 20 traditional healers, 50 drugstore staff and 30 guesthouse staff (see ). Trained interviewers administered face-to-face questionnaires. Providers were asked to estimate the proportion of their clients who were aged 15–24 and unmarried, their experiences and attitudes towards provision of contraceptive services to unmarried youth, their perceptions of the availability and accessibility of family planning services for young people, and the extent of confidentiality and privacy young people could count upon.

Frequency distributions are presented to describe the perspectives of providers, their characteristics and their attitudes regarding contraceptive services. Much of the analysis compared the experiences, attitudes and behaviour of formal and non-formal care providers. This was undertaken using cross tabulation where the variables are categorical, or difference in means where the variable of interest is measured at an interval level. Qualitative data were coded based on the major themes and analysed by comparison between formal and informal care providers.

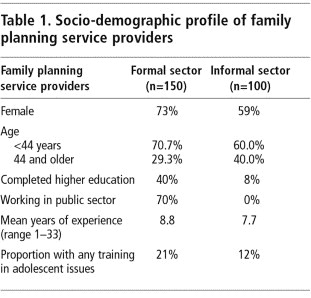

A sociodemographic profile of providers demonstrates large differences in their education, training and employment status. Both groups were largely comprised of women, but those in the formal sector were more likely to be employed in the public health services and in general more likely to be well educated. They were also more likely than the informal sector providers to have had training in adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues (20.7% vs. 12%, p=0.000) and in STI care (48.4% vs. 25%), but less in HIV/AIDS care (19.4% vs. 41.7%).

Provision of contraceptive counselling and supplies to unmarried youth

Three-quarters of providers from both the formal and informal sectors, irrespective of sector, sex, age or educational status felt that unmarried youth did not have adequate access to contraceptives. At the same time, all providers interviewed reported that unmarried youth constituted a sizeable minority of their clientele—about one in five (21%) of those served by informal sector providers and one in six (17%) served by formal sector providers (data not shown). Overall, almost two-thirds of providers served unmarried youth, at least to some extent.

In the in-depth interviews, providers were asked whether they knew the marital status of the young people who sought their services. Providers from both sectors said that if the young people were married, they were usually accompanied by their partners or came in pairs. Some informal providers said that if boys were unmarried, they came alone, while unmarried girls came in groups. Some providers said they knew the young people personally and therefore knew their marital status. A few informal providers said they did not know the marital status of their clients because they did not ask or keep records.

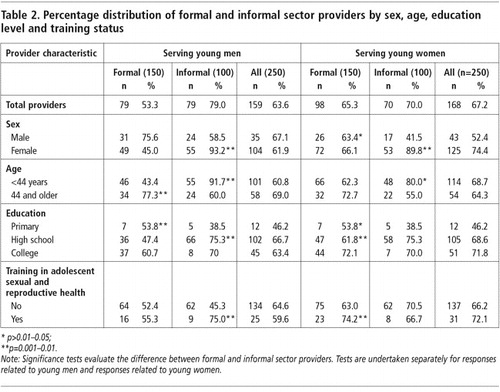

shows that a large proportion of providers, irrespective of sector or socio-demographic characteristics, were providing contraceptive services to unmarried youth. Informal sector providers were more likely than formal sector providers to say they supplied contraceptives to unmarried young men and women (79% vs. 53.3% for unmarried young men, p=0.000 and 70% vs. 65.3% to unmarried young women, p=0.002). Clear differences are observed between formal and informal sector female and male providers, e.g. female non-formal sector providers were significantly more likely to provide services to young men (93.2% vs. 45%, p=0.000) and young women (89.8% vs. 66.1%, p=0.001) than were their formal sector counterparts. The findings also suggest that male providers were more likely to provide services to young men, and female providers to young women in both sectors.

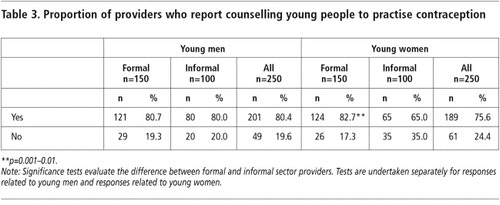

As can be observed in , large proportions of providers, irrespective of type, reported that they counselled unmarried youth on contraception. For example, 80.4% and 75.6% of providers reported that they counselled unmarried young men and women, respectively, to practise contraception. While formal and informal sector providers were about as likely to counsel young men on contraceptive use (p=0.896), formal sector providers were significantly more likely than informal sector providers to counsel unmarried young women (83% vs. 65%, p=0.001). Trained providers, irrespective of type, were more likely than others to provide counselling to young women (59% and 40%, p=0.000 respectively, data not shown).

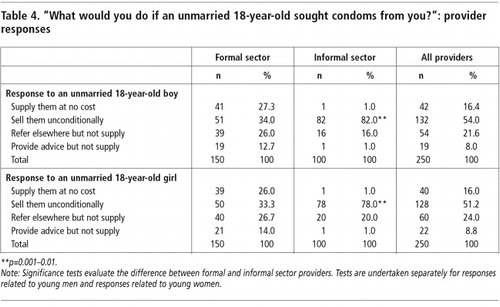

When asked what they would do if an 18-year-old unmarried young man or woman came to them seeking condoms, the large majority of respondents—60% of formal sector providers and 83% of informal sector providers—said they would provide condoms either free or for a fee, irrespective of sex (). They seemed only mildly less likely to serve young women than young men.

In general, then, in the in-depth interviews, both formal and informal sector providers said they did not refuse to provide contraceptives to unmarried youth. Yet informal sector providers suggested more strongly that it was their responsibility to help youth to protect themselves and their partners from infection and unwanted pregnancy.

“I do provide contraceptive services to married and unmarried youth because I would like to help them not to be at risk. The other reason is that I can earn money. And it is my responsibility to provide services and help society, especially to prevent youth from getting infections and pregnancy before marriage.” (Informal sector provider, woman, aged 40)

As regards charging for contraceptive supplies, of the formal sector providers who said they would provide a contraceptive method to an unmarried young person, more than half would charge, while most informal sector providers would charge (33.3% vs. 82%, p=0.000 for young men and 33.3% vs. 78%, p=0.000 for young women).

What was disturbing in many cases, however, is that a substantial minority of providers preferred not to supply contraceptives to young people. About one-third of all providers—40% of formal and 20% of informal sector providers—said they would give a referral or counselling services but not contraceptive supplies per se, and key informant interviews supported this finding. Indeed, a considerable minority argued against the provision of contraceptive supplies to unmarried youth as a general principle, and unmarried young women in particular. Typically, they justified this on the grounds that it was wrong according to Lao culture and custom, and encouraged drinking, sex and the spread of disease.

Discomfort in communicating about sex and contraception with unmarried youth

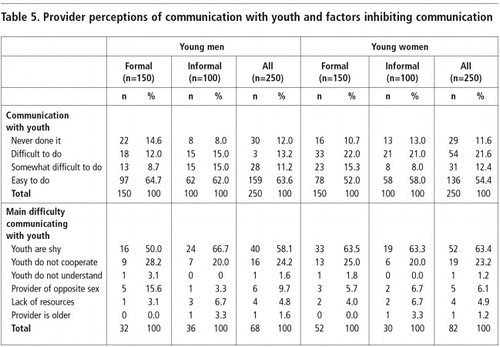

The discomfort of providers to discuss contraception with unmarried young people, particularly girls, was also evident and warranted further probing. This revealed that 13% of providers reported difficulty in discussing contraception with unmarried young men and 22% with unmarried young women (). Male providers seemed to find it easier to communicate with young men than young women, which might be due to cultural constraints and double standards. However, the difference between sex of the provider and communication about sex and contraception to boys and girls was not statistically significant (p=0.150 for young men and p=0.993 for young women).

In-depth interviews with providers suggested that although contraception may be discussed, the discussion tended to be superficial, and in general they were reluctant to discuss contraceptive options or explain the advantages, disadvantages and how to use the different types of methods.

“When an unmarried young person comes to ask for contraception, they just indicate the kind of contraceptive they need. Sometimes they show me the type of pill they want, without asking any questions. If I have that kind of pill, I provide it without counselling or explaining any advantages, disadvantages or how to take it.” (Informal sector provider, drug seller, woman, aged 35)

Providers' reasons for this diffidence about communicating with unmarried youth are listed in . All providers, irrespective of type, tended to point to characteristics of youth—shyness and lack of cooperation in particular—as the main reasons why discussion of contraception was inhibited. Half of formal sector providers mentioned young men's shyness, and 64% reported shyness with young women. Among informal sector providers, gender-related disparities were less stark (58% and 63% respectively). In contrast, providers' did not mention their own inhibitions or discomfort.

As regards lack of cooperation, about one quarter of all providers, irrespective of type, reported that unmarried youth did not follow their recommendations, tended to require extensive counselling and were otherwise difficult to convince or did not listen to them.

“It is difficult to deal with unmarried boys because they do not listen to the advice… but return to their old behaviour.” (Informal care provider, woman, aged 36)

“Unmarried girls are shy and don't want to tell the truth.” (Formal sector provider, woman, aged 31)

In the in-depth interviews, providers focused on young people's lack of cooperation in several other ways too: problems in understanding information and advice, unwillingness to engage in open discussion, and failure to keep appointments or provide sufficient information to enable follow-up. Several informal care providers also noted that young people could not always afford to pay for contraceptives.

A third reason was inhibition on the part of young people to discuss sexual matters with providers of the opposite sex to themselves, believed to be a problem by 10% and 6% of all providers with regard to young men and women respectively. Further, in the course of the in-depth interviews, it emerged that some providers also found it easier to communicate with young people of the same sex as themselves:

“It is easier to talk with young women than young men because they are afraid of getting infections and do as they are advised.” (Informal care provider, woman, aged 35)

“Talking with adolescent boys is easier than girls when we health providers are the same sex as they are.” (Formal care provider, man, aged 38)

Confidentiality and concerns about privacy

In studies in a number of countries, unmarried youth, especially young women, have argued that fear of lack of confidentiality and concerns about breach of privacy posed a major barrier to their seeking contraceptive services.Citation8 Citation9 Citation10 In this study, providers were probed about their attitudes and practice in this regard. The findings suggest that formal sector providers are more concerned with these matters than informal sector providers.

Formal sector providers described at length the measures they took to ensure privacy and confidentiality. Many reported that access to patient records was restricted to relevant health staff (and in cases of sexual coercion, the police). In contrast, the majority of informal care providers did not keep any patient records.

“… [As to] my patient records, including for unmarried youth… only my nurse and I can access those records. As to privacy, I try to examine my patients and consult them on my own. The nurse sits outside the examination room.” (Formal care provider, male, aged 35, Vientiane provincial hospital)

Most providers, both formal and informal sector, reported in both in-depth interviews and the survey that consultations kept confidentiality. However, as many as 18% of them, irrespective of type, said they did inform parents if their unmarried children had sought services from them:

“We do not inform parents if they are not present initially because it would look as if we were accusing the children if we did so, and this could impact back on them.” (Drugstore, woman, aged 35, Vientiane Municipality)

“If we know the parents and we're neighbours, we should inform the parents, so they can bring the child to us for treatment or counselling.” (Nurse, woman, aged 39, Family planning unit, Vientiane provincial hospital)

Similarly, in both in-depth interviews and the survey, formal sector providers were far more likely to report that they used a private room to see young people compared to informal sector providers (68% vs. 29%, p=0.000, results not shown). Staff in guesthouses acknowledged the relative lack of privacy; guests typically sought condoms at the counter, although in some cases, clerks provided condoms to guests in their rooms. With traditional healers, services were typically provided in their own homes, and privacy was rarely assured.

While many providers acknowledged the need to ensure privacy to young people, some formal sector providers argued that privacy need not be improved, and some informal sector providers argued that since their facilities were neither clinics nor hospitals, there was no expectation of privacy to begin with.

Discussion

This study suggests that providers of contraceptive information and supplies are influenced by traditional Lao norms, which disapprove of pre-marital sexual activity and stigmatise unmarried youth, especially young women, who seek contraceptive services. Many providers in this study showed a reluctance to supply contraceptives to unmarried youth even though they might refer them or give them information or counselling. A large minority experienced discomfort in communicating with or counselling unmarried youth as well, though this may be true of their dealings with older and married service users too. While a large proportion believed they were serving the contraceptive needs of unmarried youth, the range of services they were offering was far more limited than some of them acknowledged. Finally, a significant proportion of providers seemed judgemental of the sexual behaviour of unmarried youth, and complained that they did not cooperate with or understand them or were too shy to communicate with them.

Fees were also being unduly extracted from some unmarried young people. Indeed, among those providers who reported they were willing to supply contraceptives to unmarried youth, only a minority, largely 45% from the (smaller) formal sector,Footnote* would do so at no cost. Young people's access to money is limited because their main source of income is mainly from parents, so the cost of contraceptives, especially in the private and informal sector, could be a barrier for them. This is of concern in a setting in which government-supplied contraceptives are supposed to be provided free or at a nominal charge.

Finally, issues of confidentiality and privacy must be stressed. When young people are assured that providers will respect their right to confidentiality, they are more likely to seek care.Citation10 Findings reported in this study highlight a relative lack of sensitivity among many providers in both sectors to the need for confidentiality of unmarried youth. As many as 18% of providers perceived it to be their duty to inform parents of their children's sexual activity in the hope that parents might exert influence on their children to refrain from sexual relations. Privacy, in addition, was rarely guaranteed by informal sector providers.

Although young people sought contraceptive services from both sectors, informal sector providers—particularly women—were more likely to provide services to them than formal sector providers. Several factors may underlie this. For one thing, informal health sector providers tend to be more accessible, with facilities located close to main streets with longer opening hours. For another, providers thought young people perceived there to be greater anonymity in seeking care from informal rather than formal sector providers. Providers also believed that unmarried youth may be less likely to fear lack of privacy or the chance of being observed and identified as sexually active by neighbours and acquaintances in informal sector facilities.

Recommendations for programmes

Caution must be exercised in generalising from these findings as purposive sampling was employed and analysis was limited. Findings are largely descriptive, and may not be representative of Lao PDR generally or even of the provinces from which data were drawn.

Nevertheless, these findings offer two major recommendations for action. First, they argue for strengthening and reorienting training for providers to incorporate new messages on service provision to unmarried youth. This study has highlighted the ambivalence of providers, their discomfort in communicating with unmarried youth and in providing them contraceptive supplies. Both formal and informal care providers need to be trained in communication and counselling techniques and skills required for serving unmarried youth. Training must reinforce young people's rights to confidentiality, and dispel any doubts that contraceptive services for the unmarried lie outside the mandate of formal sector providers. Informal sector providers, likewise, need to be apprised of young people's rights, and their need for information and counselling.

Second, programmes must ensure that quality services are provided to unmarried youth, and that unmarried young people have access to contraceptive services and supplies free of charge in government clinics or at a nominal charge, that providers are equipped with appropriate informational materials as well as supplies and information for appropriate referrals, and the means to ensure privacy and confidentiality.

Finally, further research is needed to learn more about the attitudes and experiences of young, unmarried youth in regard to the provision of contraceptive services. For better informing youth, the WHO Strategic Assessment in 1999 recommended making better and more extensive use of the vast network of the Lao Youth Union (LYU); expanding use of the media for dissemination of essential reproductive health messages; increasing educational levels of young people; and promoting an already growing recognition of the problem by policymakers.Citation4

These measures are a necessary first step towards providing youth-friendly services providing condoms and contraceptives in Lao PDR, and reducing barriers to accessing services on the part of young, unmarried men and women.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, World Health Organization. Special thanks to Dr Philip Guest and Dr Shireen Jejeebhoy for their technical assistance and encouragement.

Notes

* Data were not collected on the amounts charged in either sector.

References

- United Nations Population Fund. Programme Review and Strategy Development Report. 1997; UNFPA: New York. Unpublished.

- National Statistics Centre. National Reproductive Health Survey. UNFPA Project Lao/97/PO7. 2000; UNFPA: Vientiane.

- S Mehta, R Groenen, F Roque. Asia–Pacific Population Policies and Programmes: Future Directions Report, Key Future Actions and Background. Papers of a High Level Meeting. Asian Population Studies Series, No. 53. 1998; United Nations: New York.

- World Health Organization. Strategic Assessment of Reproductive Health in Lao PDR 1999. WHO/RHR/00.3. Geneva: Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, WHO and Lao PDR Institute for Maternal and Child Health and Ministry of Health, 2000.

- United Nations Children's Fund. National Birth Spacing Policies. Project Lao 93/PO3. 1995; UNICEF: Vientiane.

- United Nations Children's Fund. Results and Recommendations from a Maternal Health Needs Assessment in Three Provinces of the Lao People's Democratic Republic. Presented to the Royal Netherlands Embassy, Bangkok. (Unpublished)

- United Nations Children's Fund. A Situation Analysis: Children and their Families in the Lao People's Democratic Republic. 1996; UNICEF: Vientiane. Unpublished.

- A Middleman, S Emans. Adolescent sexuality and reproductive health. Comprehensive Therapy. 21: 1995; 127–134.

- Brown A, Jejeebhoy S, Shah I, et al. Sexual relations among young people in developing countries: evidence from WHO case studies. Occasional Paper. Geneva: WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2001.

- J Hughes, AP McCauley. Improving the fit: adolescents' needs and future programs for sexual and reproductive health in developing countries. Studies in Family Planning. 29(2): 1998; 233–245.