Abstract

Since the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, the need for sexuality education for youth has been articulated, and numerous activities in Indonesia, especially Java, have been directed at young people. However, many parents, teachers and religious leaders have considered it essential that such education should suppress youth sexuality. This article reflects upon current discourses on youth sexuality in Java as against the actual sexual behaviour of young people. Using examples from popular magazines and educational publications, and focus group discussions with young men and women in Surabaya, East Java, we argue that the dominant prohibitive discourse in Java denounces youth sexuality as unhealthy, reinforced through intimidation about the dangers of sex. In contrast, a discourse of competence and citizenship would more adequately reflect the actual sexual behaviour of youth, and raises new challenges for sexuality education. Information should be available to youth concerning different sexualities, respecting the spectrum of diversity. Popular youth media have an especially important role to play in this. The means to stay healthy and be responsible–contraceptives and condoms–should be available at sites where youth feel comfortable about accessing them. Meanwhile, young Indonesians are engaging in different forms of sexual relationships and finding their own sources of information, independent of government, religion and international organisations.

Résumé

l'intimidation en citant les dangers des rapports sexuels. Pourtant, un discours de compétence et de citoyenneté est plus adapté au comportement réel des adolescents et fixe de nouvelles tâ ches pour l'éducation sexuelle. Les jeunes doivent disposer d'informations sur différentes sexualités, en respectant la diversité des comportements. Les médias populaires parmi les jeunes ont un rôle particulièrement important à jouer dans ce domaine. Les moyens de demeurer en bonne santé et d'être responsables–contraceptifs et préservatifs–devraient être disponibles dans desendroits où les jeunes se sentent à l'aise. Entretemps, les jeunes Indonésiens pratiquent différentes formes de relations sexuelles et trouvent leurs propres sources d'information, indépendantes des organisations étatiques, religieuses et internationales.

Resumen

Desde la CIPD de 1994, se ha expresado la necesidad de impartir educación sexual a la juventud y, con este fin, se han realizado numerosas actividades en Java, Indonesia. Sin embargo, muchos padres, maestros y lı́deres religiosos piensan que esta educación debe suprimir la sexualidad de la juventud. En este artı́culo se reflexiona sobre los discursos actuales que están en contra del comportamiento sexual de los jóvenes de Java. Mediante ejemplos de revistas populares y publicaciones educativas, ası́ como discusiones en grupos focales con hombres y mujeres jóvenes de Surabaya, Java Oriental, se argumenta que el discurso prohibitivo dominante en Java denuncia la sexualidad de la juventud como no saludable, reforzada mediante la intimidación en torno a los peligros del sexo. En cambio, un discurso de competencia y ciudadanı́a reflejarı́a más adecuadamente el verdadero comportamiento sexual de los jóvenes, y plantearı́a nuevos retos para la educación sexual. La juventud debe disponer de información sobre las diferentes modalidades de la sexualidad, que respete el espectro de diversidad. Los medios de comunicación populares dirigidos a los jóvenes desempeñan un papel de particular relevancia al respecto. Los métodos para conservar la salud y ser responsable (p. ej., anticonceptivos como el condón) deben estar disponibles en lugares donde la juventud se sienta cómoda accediéndolos. Mientras tanto, los jóvenes indoneses están participando en diferentes tipos de relaciones sexuales y encontrando sus propias fuentes de información, independiente del gobierno, la religión y las organizaciones internacionales.

After the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, the need for sexuality education for youth was articulated, and numerous activities in Java, where half the population of Indonesia live, were directed at adolescents. Since the fall of the Suharto regime in 1997, there have been shifts in policy to address reproductive health and rights, and sexuality and sexual health.Citation1 At the same time, Indonesian civil society organisations, especially health activists and feminist groups, have succeeded in bringing human rights in relation to sexuality and reproduction and the needs of adolescents to the fore. Prominent here are AIDS service organisations, academic research groups, progressive media and some lesbian–gay–transgender organisations.Citation2, Citation3

Foucault identified efforts to make sexuality in the young a theme of education because of its perceived dangers, especially masturbation.Citation4 Such educational efforts rely upon moral and medical principles that describe child and youth sexuality as unhealthy and morally devastating.Citation5 Regulatory mechanisms of society, represented by parents, teachers and religious leaders, are seen as essential to suppress juvenile sexuality.

This article reflects upon current discourses on youth sexuality in Java as against the actual sexual behaviour of adolescents. We argue that the dominant prohibitive discourse in Java denies and denounces youth sexuality as abnormal, unhealthy, illegal or criminal, reinforced through intimidation about the dangers of sex. In contrast, a discourse of competence and citizenshipCitation6 would more adequately reflect the actual sexual behaviour of youth, and raises new challenges to sexuality education different from a framework of prohibition.

Our data sources include a youth magazine that explicitly deals with reproductive health; the four most popular youth magazines in 2001–03, which illustrate the imagery of youth sexuality; information from focus group discussions with young men and women in the East Javanese city of Surabaya; publications on reproductive health for youth from the past decade by international, governmental, and non-governmental organisations; and data on sexual activity among young Indonesians. We do not provide a comprehensive overview of publications and debates about youth sexuality in Java, but use a selection to illustrate our argument.

Sexuality discourses

The regulation of youth sexuality occurs through legal–moral mechanisms that allow sexuality in marriage but deny sexual activity in non-married youth, as it poses a threat to the norms which the state and religion feel responsible for. The minimum age at marriage in Indonesia is 19 for men and 16 for women.Citation7 The median age at first marriage has been rising since 1994 (currently 20 in urban areas and 18 years rurally), and the age-specific fertility rate has declined (from 76 in 1991 to 62 in 1997 in 15–17 year olds) but is still relatively high.Citation8

It is a contradiction that a 16-year-old girl can have sexual relations and pleasure within the confines of marriage, which gives her adult status and allows her access to family planning and reproductive health services. Whereas, if she is unmarried it is considered sinful, pathological or abuse and she has to face sanctions for violating societal prohibitions.

A different discourse about youth sexuality engages notions of citizenship and human rights.Citation9, Citation10 Central to this discourse is the idea of competence of adolescents: to be able to make decisions about sex in a mature way. The notion of competent citizenship includes participation, access, equal and just treatment.Citation6 The Convention of the Rights of the Child as well as the Cairo declaration about reproductive and sexual rights ascribe to youth of both sexes such competence when fully informed and having had education in these matters.

Differently from the prohibitive, regulatory framework, this discourse is permissive and builds on the enlightenment principle of rationality, in contrast to the idea of an irrational sexual drive in search of satisfaction. A citizenship discourse supports a belief in self-control through rational choice, not requiring outside controls. Nonetheless, there is also ambivalence in this discourse: adolescent sexuality is tolerated, even accepted, yet framed with concepts of rights and responsibility. Thus, youth can be sexually active but have to show care for their own and their partner's health, consent and pleasure, a position supported by progressive Indonesian civil society groups.

Discourses of prohibition and intimidation

To illustrate the discourse of prohibition and intimidation, we use two examples from a youth magazine published by the NGO Yayasan Pelita Ilmu (〈http://www.pelita-ilmu.or.id/〉) a health NGO set up in the early 1990s to work on HIV/AIDS, including for young people, who later developed work on sexuality issues more generally. The foundation operates several health clinics in Jakarta, a buddy programme for AIDS patients, a drug abuse prevention and care programme and training on reproductive health issues. It publishes a monthly magazine Warta Propas, with a circulation of 2,500, which is distributed to school-going youth and sold at kiosks.

Scene 1

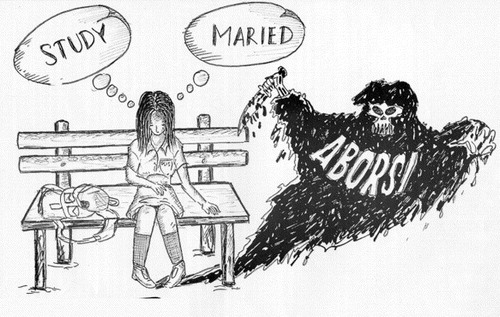

The back page of the January 2002 issue of Warta Propas contains a drawing from a caricature drawing competition, run as part of the Student Creativity Festival among adolescent pupils in October 2001. On a bench, outdoors, a girl is sitting in obvious despair. Her schoolbag lies besides her Figure 1.

The sign for OSIS (Internal School Student Organization) identifies her as a schoolgirl. She is thinking about study and marriage, posed as alternatives. The use of the words in English might indicate that she has followed Western ways by having sex. The ghost with a skull for a face draws immediate attention, along with the black (or bloody?) Indonesian word aborsi (abortion) on its chest, holding a knife from which drops of blood are falling.The alternatives of study or marriage are not pictured as horrendous. Though study may be more desirable than marriage, the only really frightening idea is abortion for this, we assume, pregnant schoolgirl. Questions arising from the drawing might be: Is abortion the worst thing that can happen to a pregnant girl? Abortion, would it kill, with a knife? Or does the knife suggest the embryo would be killed? Would she be able to continue her studies? Would she be able to marry after having aborted? Would she, a pregnant teenager, have to marry if she did not have an abortion? Why would an abortion not be seen as relief? Why is it a bloody horrible ghost? Is abortion the ultimate sin? Is it so frightening?

Was the artist a girl, showing her own problem? Or did the artist want to warn others? Was it a he? Is the drawing an cry of despair or protest against the lack of accessible, affordable and safe abortion services? Is the drawing an accusation against the dangerous, painful and illegal abortions to which young Indonesian girls have recourse? Is the drawing, and this is what we suspect, a warning against sexual relationships during school years–sex that forces you to give up your studies, your hopes for a good marriage, sex threatening your life? Is the message of this drawing an appeal for abstinence, virginity, repression of sexual desires? And isn't the threat of an unsafe abortion the most drastic warning possible against sexual relations for a young adolescent student?

There is no young man in this drawing. Didn't she love him, have pleasure with him, desire him? Is her pregnancy the result of rape, violence, date rape, incest, all of which girls are made afraid of? Is she a victim of her own or an older or young man's desires? In this scene of fear, he is absent. What does the drawing tell us about this timid, lonely girl? “Grrl” power? Not in this scene. Gender relations, sexual relations are missing; we are confronted only with pregnancy as consequence and as nightmare. Sexuality and horror. Sexuality as horror.

Scene 2

In the same issue of the Warta Propas magazine there is a long article entitled “Chatting. Berguna atau malah berbahaya?” (Chatting: useful or dangerous?)Citation11 This time, it is boys who are in danger. The article reports the story of a 17-year-old boy with homosexual interests who was invited after a cyber chat to a Gay and Lesbian Room, where he met a 25-year-old man who said he would introduce him to the gay world. He was taken to an apartment where he was raped by two men, who tied his feet and covered his mouth with tape. The boy suffocated and died. The perpetrators cut up his body, put the parts in a suitcase and left it in front of a post office. The police found the murderers, who insisted that the boy's death was an accident.

The message is to watch out for cyber sex; you start with chatting and you end up being raped and murdered. Don't trust men in the cyber world, they can find you, your phone number and address, and kill you. Look for safety, have positive aims which also can bring fun, look for healthy entertainment, distance yourself from those who intend to harm you–that is the advice at the end of the story. Again there is a link between sex and danger, sex and death, and boys are not safer than girls. Homosexual encounters can be as dangerous as heterosexual ones. Be careful, awas! Gaul itu perlu, tapi jangan kebablasan! You need to be cool, but don't go too far!

This destructive image of sex as the terminator of life, status, chances and hopes is channelled into education discourses, illustrated in the publications of the three most influential family planning organisations in Indonesia: PKBI (Indonesian family planning association), UNFPA (UN Population Fund), and BKKBN (National Family Planning Coordination Board).

A PKBI poster, for example, uses a similar, though less dramatic message than the Warta Propas article “Bergaul boleh, sex - no way” (Have fun, but no sex). PKBI has explained that such a strong “no” to adolescent sex is promoted due to the absence of contraceptives for youth and unmarried persons and a law that forbids abortion. Sexual permissiveness, they say, would have catastrophic consequences–unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases, giving up ambitions, exposure to crime and destruction of one's life. PKBI uses pragmatic reasons of harm prevention for its campaign, not ideological ones. Yet, this pragmatism coincides with religious beliefs (no sex before marriage) and state policy (family planning and reproductive health services only for married couples), supporting the same principle.Citation12

The website of PKBI of West Java also provides a long list of reasons why sex before marriage should be prevented. The main reason is that the risks are too high (unwanted pregnancy, guilt feelings, STDs, HIV/AIDS). Furthermore, religious prohibition is cited–sex is sacred and meant for procreation, therefore sexual relationships should only be realised in sanctioned forms of commitment and responsibility. Consequently, abstinence is the best form of pregnancy prevention, requiring commitment, motivation and self-control. Sex should not be the expression of love either, the site says. Rather, sex would prevent the couple getting to know each other, because of the sexual satisfaction one achieves. So what should the adolescent do? “Repress your sexual desires! Don't touch erotic body zones, because the nerves there would increase your sexual drive, which would weaken your self-control! Do things together with your boy/girl friend that are non-sexual… Adolescents have sexual relationships for proof of love, separation fear, curiosity, the belief that sex is common, pleasure, no fear of STDs or pregnancy, money, trivialisation of sex, lack of self-control and demonstration of sexual prowess. What would prevent an adolescent from having sex? Fear of the consequences, obedience to parents, fear of violence, friendship, consciousness of sinfulness, immaturity and fear of loss of virginity… To prevent sex, decide your boundaries, don't drink alcohol, don't take drugs, be firm in your resistance, don't get dependent on someone else, be open about your refusal, mistrust, don't go to isolated places, don't meet your friend, and pray. If you follow this advice, you will be a healthy couple (Pacaran Sehat), physically, mentally and socially healthy.”Citation13

In this discourse of self-regulation, a new moral principle of responsibility is asserted–responsible abstinence.Citation13 This assemblage of warnings, advice and promises culminates in the slogan “Bergaul boleh, sex–no way”. Thus, youth should vanquish their sexuality through self-restraint.

Nowadays, the period of adolescence has been extended through further education and training. The abstinence discourse is supported by an older family planning discourse of the desirability of greater education for girls because of the correlation between female education and later marriage, which eventually leads to lower fertility.Citation14, Citation15

However, all these good reasons for abstinence in adolescence, appealing to rational decision-making on issues of morality, seem to need to be complemented by not-so-rational horror stories and fear-mongering. These vast efforts to inculcate behavioural change and prevent unacceptable sexual activity raise the question of what adolescent behaviour in sexual matters actually is.

Data on adolescent sexual behaviour in Indonesia

The BKKBN website reports that in the 1990s, 20–30% of youth living in the Javanese cities of Bandung, Bogor, Sukabumi and Yogyakarta engaged in premarital sex. The biggest survey to date, conducted in 1998 among 4,106 men and 3,978 women aged 15–24 in West, Central and East Java and Lampung in southern Sumatra, found that although most respondents disapproved of sexual activity before or outside marriage, 12% approved premarital sex if the couple were planning to marry.Citation16

A much smaller study among 210 students (aged 15–24) who were sexually active and unmarried found that more than half had had sex after a year of acquaintance with a partner. In addition, some youths had regular commercial sex encounters and others homosexual encounters, and a few attended “orgies”. This author also pleads for control of sexual urges (disiplin hasrat).Citation17

A study in Java by PKBI in 1994 found that of 2,558 abortions, 58% were in young women aged 15–24, of whom 62% were not married. Nine cases were in girls under the age of 15.Citation18 A qualitative study in 2002 of premarital pregnancy in 44 adolescents in Yogyakarta, found that 11 of 18 pregnant girls (aged 15–20) had had an abortion and 17 others had given birth. More young women with higher education chose abortion, whereas those with less education gave birth. The reasons given for unprotected intercourse were lack of knowledge about the consequences of sexual acts and impulsiveness.Citation19

In many cases, marriage is forced on young people who may not be economically or socially prepared for it, often resulting in early divorce. In the survey already mentioned, 13.1% of young men and 23.1% of young women who had married said they were forced to marry by their parents (reasons not stated), and two-thirds of them felt that they had married too young.Citation16 Hypocritically, the detrimental effects of forced marriage are rarely acknowledged.

All these studies indicate that a substantial minority of adolescents are sexually active, though “active” is not defined. A study in 1994 of sexual behaviour in urban, Jakartan, middle-class youth by Utomo provides details on this question. Of 344 high school students aged 15–19, 7% of boys and 2% of girls had had intercourse. Other sexual expressions like kissing on the lips (23%) and breast (18%) and genital fondling (11%) were reported by more boys than girls. 80% of adolescent girls felt that premarital sex would never be right, but others were positive about premarital sex if contraceptives were used (16%), there was mutual agreement (5%), in the case of love (20%), if the parents-in-law had already proposed (13%), if already engaged (21%) or if a male prostitute was involved (4%). The attitudes of the boys were quite similar to those of the girls, but 10% felt premarital sex was all right with mutual agreement and 14% if it was with a prostitute. In general, Muslim youth had less sexual experience than non-Muslims and significantly more conservative beliefs than non-Muslims.Citation20

Open discussions with young people

In order to gather qualitative information on sexual activity among university students, Oetomo conducted focus group discussions with five young women and four young men who were already analysing issues of gender and sexuality with him. They were aged 19 to 25 and from both rural and urban backgrounds. There were three sessions. Four of the five participants in the first session took part in the third one as well, as did one of the four in the second discussion. The first and second sessions were based on scanning one issue each of three popular youth magazines, chosen randomly. The keywords gender and sexuality were used to provoke discussion. The third discussion was based on a series of questions about the participants' sexual practices and those of their friends, and the meaning of these practices. Oetomo and a facilitator led the discussions.

For these young people, partner choice was very important. Most of them said that ideally their partner would resemble a young singer or film star, with a light skin colour, “baby face”, straight hair, tall body and muscular. Others added criteria such as same religion, economic security, competence and responsibility. Some girls wanted their boyfriends to look like their father. Boys wanted a girlfriend who looked fresh, voluptuous or thoughtful. Most were conscious that those characteristics were not easily found.

In this group, seven had engaged in sexual activities, with a partner or alone. On a rating set by the group from one to ten, with one for manual stimulation and ten for intercourse, two-thirds of the group rated their behaviour between five and ten - with boys from seven to ten and girls five to seven, which meant sexual stimulation without undressing. Girls said that they engaged sexually because of feelings of love, desire for pleasure and curiosity to try something they had heard or read about. Most girls only stopped sexual activities from concern about the risks of pregnancy, abortion, punishment by parents or social exclusion. Only a few thought they should maintain their virginity until marriage. Only one refrained from sex for religious reasons. The boys said their sexual activities were motivated by affection, physical desire, curiosity and the search for creativity in trying out something new. Religion did not play a role for them. Boys said that they reduced the risks of pregnancy by coitus interruptus, anal sex or use of contraceptives.

Their sources of information on sexual activity and contraception were friends, youth journals, blue movies and mimeographed erotic magazines, and also parents and the sex education package at school. Interestingly, none of them had read a publication about sexuality or contraception from official government sources or NGOs, nor was the Internet mentioned. In educational sessions at school, they had learned about the reproductive organs, menstruation, hygiene and the dangers of intercourse, and also about the contraceptive pill and condoms. One participant said that warnings had not affected him; on the contrary, he wanted to have sex, but safe sex.

The youth in our sample did not seem to be impressed by proscriptions by state and religious sources; they relied on their own will and found the information they needed. They were not activists for sexual rights, but young citizens living a right that officially is denied to them.

Content of popular youth magazines

Exposure to the media, especially to Western music on television and radio, radio news and popular science reports, and science and health programmes on television are “strong predictors of the behaviour and attitudes of young people” according to Utomo and McDonald.Citation21 In a small survey of four popular youth magazines,Footnote* we did not find preachy remarks of the prohibitive kind nor permissive remarks from nanny-like parent-figures who treat youth as objects incapable of taking care of themselves. Those magazines are about celebrities from film, music, sports, fashion and recreation, and invite readers to write in about their lives, events in school, problems with family and friends, and ask questions regarding (heterosexual) relationships. A number of letters to the editor were from young people asking explicit questions about sexuality, e.g. same-sex practices and anal sex. Our sense was that the magazines, being commercial, had appraised the demands of their readers and responded to them (Interview by Oetomo with editors of Hai, March 2001).

Discourses of citizenship, competence and rights

When youth are recognised and respected as a social group, the issue of citizenship comes to the fore. Citizenship means first and foremost rights and entitlements as well as responsibility. The Convention on the Rights of the Child ascribes to children the right to freedom of expression and information (Article 13), while the ICPD Programme of Action 1994 says that adolescents have a right to reproductive health education, information and care, and calls on countries to establish appropriate programmes to respond to these needs and to strive to reduce STDs and pregnancy among adolescents (Paras. 7.46 and 7.47).

The International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF) Youth Manifesto, developed by young people from all six IPPF world regions in 1998, states three goals:

| • | Young people must have information and education on sexuality and the best possible sexual and reproductive health services (including contraceptives). | ||||

| • | Young people must be able to be active citizens in their society. | ||||

| • | Young people must be able to have pleasure and confidence in relationships and all aspects of sexuality.Citation22 | ||||

On the basis of these rights, young people could claim, for example, the right to contraceptive services, irrespective of their marital status. This position is taken by Utamadi, a reproductive health activist with PKBI in Yogyakarta, in an article in Kompas, the biggest national newspaper. He points out the failure of the Indonesian state to protect children from hazardous work and trafficking, and the fact that pregnant teenage girls are forced to marry and leave school. He contends that adolescents must know their rights in order to be able to lobby for them.Citation23

A non-prohibitive sexuality discourse for youth builds on a belief in their ability to balance needs with rights. Yet, ascribing sexual and reproductive rights to adolescents cannot be separated from ensuring they have the competence to live out those rights. In our view, competence regarding sexuality has several dimensions: factual knowledge about the physical processes of one's own body and the body of a partner, fertility and contraception and the existence of and protection against sexually transmitted diseases. Interactive knowledge would mean respectful communication and empathy with a partner. Such knowledge cannot be generated only by often under-informed peers or commercial youth magazines. It requires education that includes discussion and reflection and services that provide access to condoms, contraceptives and safe abortion.

The Indonesian Consumer Association has published on these matters for the NGO community in Indonesia,Citation24 and elaboration of reproductive and sexual rights was the subject of exposure tours for 22 representatives of Indonesian NGOs to the Netherlands in 2002.Citation12 The Lentera initiative of PKBI has the potential to provide services for adolescents in a non-repressive manner. The volunteers who started Lentera reached out to marginalised groups such as street children, female sex workers and gay-identified and transvestite men in a non-patronising way and worked with them to advocate sexual rights.Citation25, Citation26 Interestingly, a large number of progressive NGO activists have begun standing for election to local, provincial and national legislatures, and this will eventually affect policy, as they engage with more conservative sectors.

In September 2003, a spokesman for the Indonesian Ministry of Justice and Human Rights announced on behalf of the Minister that a new draft Criminal Code would be tabled in Parliament:

“The planned sexual behaviour laws…include prohibitions against adultery and cohabitation between adults, and oral sex and homosexual acts between youths under the age of 18. Punishment for these sexual crimes would be up to 12 years in jail. Citation27

The reaction to this by all but a few ultraconservative Islamic media was refreshingly strong. Human rights activists criticised the Minister's attempt to bring sharia rules into national Indonesian law. Journalists and their interviewees were outraged, and headlines such as “We don't want the state in our bedrooms” were splashed across the front pages of the newspapers.Citation28

Non-prohibition or allowance of sex is not based on a concept of drives and instincts determining behaviour but rather on a holistic concept of the capacity to be rational about sexual interests. Non-prohibition does not mean “you must have sex”; on the contrary, it means having information and the acceptance of desire, dialogue, negotiation and pleasure. This is the meaning of empowering young people in relation to sexuality.

Conclusions

Until a political agenda is developed that dares to turn the discourse of prohibition into one of honesty and respect for adolescents' needs and rights, young women and men, whether heterosexual or homosexual, will be confronted with expectations that they should remain innocent and abstinent at a time when they are seeking to understand the sexual functions of the body and act respectfully towards partners.

In our study of the literature and discussions with young people, we found them to be rather active sexually. They were curious, experimenting and unafraid, but also careful. Young people know quite a lot and want all the information they can get–and they want to be recognised as responsible beings. The images of young people we encountered in discussions and popular magazines are contrary to those representing youth as frightened of the terrible consequences of sexuality and needing protection. Rather, we found young people who are exploring an experimental field of pleasure for themselves–with some caution and with responsibility–a field segregated from adults. If prohibition does not prevent young Indonesians from experiencing their sexuality, what discourse about adolescent sexuality is of value?

If sexuality is a form of knowledge-seeking that creates identity and connectivity, then sexuality is not something dangerous that should be suppressed. Young people can have a healthy, informed and responsible sexual life. Information should be available concerning the complexities of different sexualities, respecting the spectrum of diversity. The means to stay healthy and be responsible–contraceptives and condoms–should be available at strategic sites where youth feel comfortable about accessing them. Meanwhile, young Indonesians are engaging in different forms of sexual relationship and finding their own sources of information, independent of government, religion and international organisations.

By providing information and the means to sexual health, we actually reduce the risk of young people inflicting harm on themselves. The ideal, in our opinion, are sexually street-wise youth who know when not to engage in sex, and when they are engaging, know how to protect themselves from unwanted outcomes, whether pregnancy, STIs or HIV, and for gay youth from futile experimentation with heterosexual relationships. Popular youth media have an especially important role to play in putting knowledge in the hands of youth, to help them to be responsible. In addition, policy on adolescent sexual activity should conceptualise youth as a life stage in which more than just sexuality is at issue.

In many ways, young Indonesians are fortunate to be living in a country with one of the freest presses in Asia and where the freedom to discuss sexuality is growing, at least in urban areas. International donors have also woken up to the complex realities of sexuality, and have felt less constrained to fund programmes for educating different sectors of society, including government itself, about sexuality. By far the most advanced are the HIV/AIDS and STI prevention and care programmes now operating in almost half the country's provinces. Young people are an important target of these programmes, not only heterosexual youth but also young people who are sex workers (female, male and transgender), homosexuals, transgenders and transexuals. In many instances, it is young people who are educating programme managers and funders about different sexualities. Other organisations, including those working on reproductive health and women's organisations, are not responding as quickly to these new perspectives, but trends in the media and amongst funders are slowly affecting them as well.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a revised version of a paper presented at the European Social Science Java Network Conference on Youth and Identity, Université de Provence, Marseilles, 2–5 May 2002. Our thanks to Danny M Goenawan and Kholid Fathirius, who facilitated focus group discussions. Translation of text from Indonesian to English was by the authors.

Notes

* Aneka Yess! (No. 20, 25 Sept–8 Oct 2003), Gadis (Vol. 30, No. 26, 26 Sept–6 Oct 2003), Kawanku (Vol. 27, No. 37, 15–21 Sept 2003), and two issues of HAI, one for young women (Vol. 27 No. 37, 15–21 Sept 2003) and one for young men (Vol. 27 No. 38, 22–28 Sept 2003).

References

- TH Hull. The political framework for family planning in Indonesia. Three decades of development. F Lubis, A Niehof. Two is Enough. Family Planning in Indonesia under the New Order 1968–1998. No. 204. 2003; KITLV Press: Leiden, 57–82.

- BM Holzner, N Kollmann, S Darwisyah. East-West Encounters for Reproductive Health Practices & Policies. Indonesian NGOs meet Dutch Organisations. 2002; AKSANT: Amsterdam.

- K Purwandari, NKE Triwijati, S Sabaroedin. Hak-hak Reproduksi Perempuan Yang Terpasung. 1998; Sinar Harapan: Jakarta.

- M Foucault. The History of Sexuality. Vol. I, An Introduction. 1976; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth.

- F Mort. Dangerous Sexualities. 1987; Routledge & Kegan Paul: London.

- Reynolds P. Citizenship, sexuality and youth: some conceptual considerations. In: Crawford K, Straker K (editors). Conference Proceedings. Citizenship, Young People and Participation. Lutterworth: Leicestershire, 2000. At: 〈www.mmu.ac.uk/c-a/edu/research/citizen/〉. Accessed 8 February 2003.

- Reproductive Health, Women's Health in Southeast Asia. At: 〈http:/w3.whosea.org/women/chap3_1.htm〉. Accessed 20 January 2004.

- Utami Adolescent and Youth Reproductive Health in Indonesia. Status, Issues, Policies, and Programs. POLICY Project STARH Program, January 2003. At: 〈http://www.policyproject.com/pubs/countryreports/ARH_Indonesia.pdf〉. Accessed 18 January 2004.

- G Jones, C Wallace. Youth, Family and Citizenship. 1992; Open University Press: Buckingham.

- R Lister. Citizenship: Feminist Perspectives. 1997; MacMillan: London.

- S Yola. Chatting: Berguna atau malah berbahaya?. Warta Propas. 19: 2002; 6–9.

- Report of the Final Seminar of the Reproductive Health Tours, Jakarta–Amsterdam, January 2000. Sponsored by the Ford Foundation. (Unpublished)

- Mengapa hubungan seks sebelum nikah harus dihindari, PKBI Online. Perkumpulan Keluarga Berencana Indonesia (PKBI). At: 〈http://nt.ngo.or.id/pkbi/pkbijabar/mcr/default.asp〉. Accessed 10 February 2002.

- AR Quisumbing, K Hallman. Marriage in Transition: Evidence on Age, Education, and Assets from Six Developing Countries. Policy Research Division Working Paper No.183. 2003; Population Council: New York.

- Jungho Kim. Women's Education in the Fertility Transition: An Analysis of the Second Birth Interval in Indonesia. Job Market Paper. Brown University, 5 December 2003. At: 〈http://www.econ.brown.edu/students/Jungho_Kim/Jungho_birthspacing.pdf〉. Accessed 28 January 2004.

- Hasmi E. Meeting Reproductive Health Needs of Adolescents In Indonesia, Baseline Survey of Young Adult Reproductive Welfare In Indonesia 1998/1999, Book 1. At: 〈http://www.bkkbn.go.id/hqweb/ceria/ma1meeting%20rh%20needs%20of%20adol.in%20ind.html〉. Accessed 30 January 2004.

- Hambali. Perilaki seksual remaja di Indonesia. N Kollmann. Kesehatan Reproduksi Remaja. Program Seri Lokakarya Kesehatan Perempuan. 1998; Yayasan Lembaga Konsumen Indonesia, Ford Foundation: Jakarta, 29–34.

- D Rosdiana. Pokok-pokok pikiran pendidikan seks untuk remaja. N Kollmann. Kesehatan Reproduksi Remaja. Program Seri Lokakarya Kesehatan Perempuan. 1998; Yayasan Lembaga Konsumen Indonesia, Ford Foundation: Jakarta, 9–20.

- Y Khisbiyah, D Murdijana, B Wijayanto. Kehamilan yang tidak dikehendaki di kalangan remaja. Bening. 2(1): 2002; 1–14. At: 〈http://www.pkbi-jogja.org/bening/bening003_12.html〉. Accessed 2 January 2004.

- ID Utomo. Sexual values and early experiences among young people in Jakarta. L Manderson, P Liamputtong. Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia: Youth, Courtship and Sexuality. 2002; Curzon Press: Richmond, 207–227.

- ID Utomo, P McDonald. Middle class young people and their parents in Jakarta: generational differences in sexual attitudes and behaviour. Population Studies. 2(2): 1996; 170–206.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Report of IPPF Working Group on Sexuality. 2001; 3. 12–14 November.

- Utamadi G. Remaja dan Anak Indonesia. At: 〈htpp://www.kompas.com/kompas,cetak/0207/26/dikbud/rema35.htm〉. Accessed 26 July 2002.

- A Rachman. Gelas Kaca dan Kayu Bakar. Pengalamn perempuan dalam Pelaksanaan Hak-Hak Keluarga Berencana, 1998. Pustaka Pelajar Yogyakarta dengan Yayasan Lembaga Konsumen Sulawesi Selatan, Ford Foundation. 1998; 135–146.

- Country Profile: Indonesia. At: 〈http://ippfnet.ippf.org/pub/IPPF_Regions/IPPF_CountryProfile.asp?ISOCode=ID#〉. Accessed 1 February 2004.

- Oetomo D. Advocating for marginalized sexualities and sexual and reproductive health in the Asia/Pacific context. Presented at Asia-Pacific Conference on Reproductive Health. Metro Manila, 15–19 February 2001.

- Indonesia mulls adultery law. Radio Netherlands Wereldomroep. At: 〈http://www.rnw.nl/hotspots/html/ind030930.html〉. Accessed 31 January 2004.

- Taufiqurrahman, M. Legal activists reject Code revision. Jakarta Post. [Kabar-indonesia] Indo News - 10/1/03 (Part 2 of 2). At: 〈http://www.kabar-irian.com/pipermail/kabar-indonesia/2003-October/000534.html〉. Accessed 17 February 2004.